► Ferrari 512M to the Sahara

► A CAR magazine archive gem

► Join us on our adventure

In 1995, CAR came up with a brilliant wheeze of driving a Ferrari to Africa. It was the first time we had attempted such an adventure with a Ferrari – and we were surprised when Maranello agreed. Richard Bremner is your guide, as we drive an F512M down to the sand dunes of the Sahara. Read the full unabridged story below. Also check out our latest adventure, where we retrace the original epic journey in a V12 Purosangue here.

The Ferrari is 100 yards in front, and it looks as if it’s on fire. Engulfed in the raging swirl, it is identifiable only by the fierce circular glow of its tail-lights. It’s dark, and they look like the veiled eyes of a monster. The Ferrari is edging ahead, nosing about among the soft, shadowy contours of a dirt nothingness that appears to be everywhere, and leads to nowhere. I’m watching a Ferrari F512M driving into the Sahara. The storm raging over it is not smoke but dust, Saharan sand spat by the tyres and whipped skywards by the engine’s roaring cooling fans.

It is truly, profoundly dark out here. The only light comes from our cars and a night sky spattered with stars whose glow goes unseen by most Europeans. We are alone. We are heading for the Saharan dunes of Erg Chebbi.

Why, you might wonder, would we want to take a Ferrari to the Sahara? To get a great drive, is the short answer. Morocco has some fantastic roads – jaw-droppingly scenic, open, fast, and free of radar. The sort of place where a supercar can roam unmolested by police or other traffic. I rang Shell to check the availability of unleaded in Morocco. ‘No problem,’ came the answer. ‘There are unleaded stations every 100km or so.’

We faxed Ferrari. Could we borrow a £138,000 F512M to go to Morocco for a few days, please? Well, you’ve got to try, haven’t you? But Ferrari said yes. PR man Antonio Ghini had even been thinking of an unusual road trip with an F512M. Whether this involved the Sahara he didn’t say, but yes, we could have an F512M. We hastily made our plans, wondering how long it would be before Ghini saw the lunacy of our venture.

I would take the car from Maranello out of Italy, through France and into Spain, meeting Colin Goodwin and photographer Tim Wren in Malaga. They had driven from London to Malaga in CAR’s long-term-test Vauxhall Omega, which we would use as a back-up car. We would head for Algeciras, and take the ferry to Tangier. What awaited us there we didn’t quite know…

The F512 I collect is virtually new. It has 2600km on its odometer, paint the colour of blood and a spare wheel in the passenger seat. The spare is there because an F512M has different tyre sizes front to rear. Figuring that we’ll be unlikely to drive into a Moroccan Kwik Fit and collect a Pirelli 295/35 ZR18 P Zero off the shelf should a tyre get shredded, we have a front wheel and tyre stowed up front, and a rear beside me (it won’t fit in the boot) where it is to become a sometimes over-intimate companion.

As I leave Ferrari with the precious key in my hand, Ghini’s colleague Giovanni Perfetti shouts after me: ‘When d’you think you’ll be back?’ ‘Well, I don’t quite know,’ I admit. ‘Maybe 10, 12 days – it depends.’ ‘OK. Good luck. Ciao.’ That’s it. I leave, feeling like I’ve pulled off a bank robbery.

Modena to Malaga is a long way, and though it’s mostly motorway, I don’t see Wren and Goodwin till midnight a day and a half later. But a F512M is great for a long-distance thrash like this. Keep your speeds sane (as you must in radar-riddled France) and it’s not even that noisy.

Relax as you surf on that great wave of power, listen to the flat-12 and discover that the seats are surprisingly comfortable, even after a dozen hours. There are just two problems: the spare tyre’s habit of heeling into my lap through right-handers means that I have to steer one-handed through the twists of southern Spain to support it. And, more serious, the engine has a misfire. And we’re nowhere near Morocco.

I wonder whether to try to find a Ferrari dealer in Malaga the following day. And then, as it worsens, I wonder how I’m going to get the car towed to a dealer at 11.30pm on a Tuesday night somewhere south of Alicante. But all is well: the Ferrari gets there. Perhaps it’s complaining at working a 14-hour shift. The following day, bright, blue and balmy, the misfire vanishes and our worries recede, to be replaced by thoughts of what will happen when we get to the Moroccan customs.

Mainly what happens is that we do a lot of waiting. And a lot of answering questions, plus a lot of opening its assorted lids to reveal its engine and enable the Man With A Screwdriver to check that we aren’t carrying drugs. After peering into various orifices he taps the sills and wings with such a ferocity that I wonder whether we’ll need a panelbeater.

After several hours, much arguing over Wren’s walkie-talkies – eventually confiscated – and the pay-off of various ‘helpers’ (you can’t avoid being helped if you’re a foreigner in Morocco) we’re off into the teeming mêlée of Tangier. To our first petrol station, in fact, which has unleaded. With brimmed tanks and a burst of optimism we head south-west towards Casablanca.

The road is good but slow and busy. Even in the dark you can see people’s astonishment at the Ferrari as we pass through towns, interest peaking when we’re flagged down by the police. Flashing my schoolboy French (widely spoken in Morocco, the country having been a colony) I explain what we’re doing to a baffled but friendly policeman, who wishes us ‘bonne route’. And we’re soon to have it.

Not far short of Rabat is a motorway, a new, wide dual carriageway, as black and as smooth as ebony. This is Morocco’s first péage, and when we reach the tollbooth halfway along it there is only one thing to do. The road is new, it’s deserted, it’s late at night and we have a Ferrari.

‘I want to hear what it sounds like at 150mph,’ says Goodwin. So he and Wren drive on ahead to wait for the thunder. Even a road this wide starts to feel a little narrow at 120mph, so I decide to centre the car on the white lines to bag the final 30mph. I nudge the accelerator deeper, hear the engine note drop a key as it shoulders to the task and watch the white lines lancing the 512’s nose coming at us so fast that they meld to a continuous thread.

All I can see is the Armco in the middle, the white lines and the asphalt. Everything else is black. The speedo needle closes on 150mph as the engine’s bellow is drowned by the rush of air worrying the door seals, and I can just see two lone figures and an Omega in my peripheral vision.

What does it sound like from outside? ‘A bit disappointing – you can only hear it pushing through the air and the tyre roar. We couldn’t hear the engine at all,’ reports Goodwin.

We hit Casablanca at midnight – a sprawling modern town not remotely like the Hollywood version. Booking into a preposterously expensive western hotel because it is open and promises secure parking, we retire for food. Once booked in, we discover that the secure parking consists of leaving the cars outside, where they will be eyed all night by a gardien des voitures. Figuring that he is unlikely to have a hotline to an international gang of car thieves, we leave the Ferrari to its fate, wondering only fleetingly how to make one of those ‘well, it was like this’ phone calls to Italy if it disappears.

But it doesn’t. The gardien does, however, and is replaced by another, demanding more dirhams for the morning shift. Never mind: the cars are intact. We leave, soon to turn south for Marrakech. Or so we think. Not far out of town I’m waved down by a policeman. He compliments us on the car, and asks where we are going. ‘Marrakech,’ I say. ‘And you know where you are going?’ ‘Oh yes,’ I reply, confident that since we can see the sea to our north, it will not be long before we spot a road heading south. ‘You sure?’ he asks. I confirm that I am. ‘Alors, bonne route,’ he finishes.

Five miles later we’re lost. Well, not exactly lost, because we are heading south, if on a road getting narrower, rougher and emptier by the metre. Soon it isn’t a road at all. It’s a road under construction, populated with JCBs, trucks and mystified construction workers.

Our route provides an early test of the Ferrari’s off-roading abilities, which seem rather good. It doesn’t ground, and it doesn’t get stuck. Instead, it emerges into a small village dragging a trawl of dust and the stares of amazed onlookers behind it.

We feel a little uneasy about Marrakech. The Djemaa el Fna is our goal, a large open space in the Medina where people gather to walk, talk, eat and be entertained by snake-charmers, story-tellers, musicians and fair games, which can also include tourists. It will be a pretty extraordinary place to take a Ferrari, but it may also be a one-way trip. It may get mobbed, it may get nicked and we may get threatened in the mistaken, if completely reasonable, believe that we’re loaded.

Once we’re on it, the main road to Marrakech is good – single carriageway but smooth, brisk and surrounded by increasingly barren scenery. The earth turns a pinky-orange, the route marked by groups of men selling chickens, fish and oranges which they optimistically wave at passing cars. Eventually we see Marrakech in the distance, the Atlas Mountains rising improbably behind it.

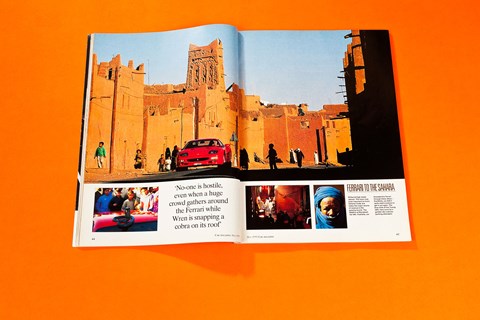

It’s a scene that makes you feel foreign, but not as foreign as you do when you drive a Ferrari into Djemaa el Fna. We do this in company with the inevitable (but essential) guide. Ashimi says that he’s been in a Ferrari before, and that he learned the catering trade at a college outside New York. It slowly dawns that the occasional smell of bull ordure is emanating not from the market but from the Ferrari’s passenger seat, but never mind – he proves a great guide, arranging snake-charmers and a drive through back alleys almost narrow enough to wedge the Ferrari.

How do people react to it? They’re amazed, amused, intrigued. Hardly anyone has heard of Ferrari, except two young blokes on a moped who ask if it’s a Lamborghini Diablo competitor. No-one is hostile, even when a huge crowd, ten deep, gathers around the car while Wren is snapping a cobra on its roof.

On page 338 of the splendid Rough Guide to Morocco is a small note, entitled ‘Winter Travel in the High Atlas’. It’s worth reading if you plan to go that way in January. We do, but we haven’t. ‘Note that the High Atlas are subject to snow from November to the end of February, and even the major Tizi n’Tichka pass can be closed for periods of a day or more,’ it warns.

Well, there’s no sign of snow south of Marrakech. It’s warm and cloudless, the road almost empty. Eventually it begins to climb, sometimes in extravagant sweeps, increasingly in tight twists demanding a hard haul on Ferrari’s unassisted wheel. Pink-orange soil gradually gives way to grey-green rock, and we pass through a village notable for nothing other than a pair of large gates, besides which a trio of snow ploughs are parked. This is the snow-line. The gates are open, and we surge on, anticipating wonderful roads. And they are.

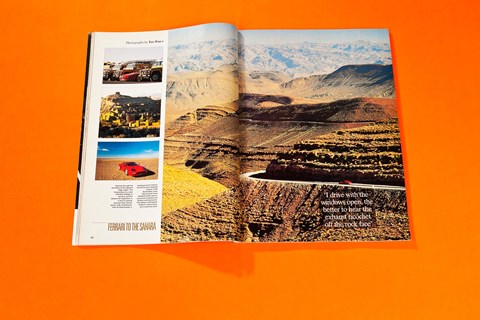

I feel like the bloke driving that Lamborghini Miura in the opening scene of The Italian Job, hurtling through curves, 12 cylinders blaring, feet skipping on the pedals, arms twirling, right arm battering the silver-balled gearstick. The difference, I’m pleased to report, is that I don’t come to a pyrotechnic end in a tunnel, although there’s plenty of scope for plunging into a ravine.

I drive with the windows open, the better to hear the exhaust ricochet off the rock face. From outside, this must sound like Armageddon. We stop for snaps near a man selling a particularly uninteresting range of rocks. ‘You’re lucky,’ he says. ‘This road is usually under three metres of snow in January.’ But there’s no snow to be seen.

As we crest the mountains the road turns worse, narrower, more ripply. Grey-green gives way to pink-orange again, only this time there’s little vegetation. Eventually we see curved shapes emerging from the ground. Dunes. Suddenly, we’re at the edge of the desert. For the first time, we feel a long, long way from home.

‘En panne, en panne.’ We are being shouted at by a Moroccan standing by a beige Peugeot 205 diesel. He has broken down – can we give him a lift to the next village? The Rough Guide advises against giving lifts in circumstances like these, but after some debate, we take the risk – we’re in the middle of nowhere and driving by seems uncharitable. And so Mohamed Ouzamou climbs aboard the Omega. He will not be getting out at the next village.

As well as Erg Chebbi, we decide to visit M’Hamid – also in the Sahara. Our road is metalled, but narrow and far from smooth, which limits the Ferrari’s pace. But you wouldn’t want to go flat out anyway, so impressive is the view. After a few miles the road begins its climb through the anti-Atlas, a ridge of mountains so visibly stratified that they appear to have been raked by a giant plough.

The drops are spectacular. The drive to M’Hamid is 130 miles and it’s 80 to Zagora, where Mohamed says he now wants to go despite the appearance of several garages. Well before that, we enter the mouth of the Drâa Valley, where we’re greeted by impossibly biblical scenes. The floor of the valley is crowded with date palms, a green carpet binding cliffs the colour of sunset. The road is peppered with villages sucking a living from the river, it’s waters tapped to irrigate the palms via a fabulously complex network of gutters and channels.

When we get to Zagora, Goodwin and Wren have established that Mohamed speaks good English, that he really hasn’t much else to do today and if we like, he can take us to some dunes beyond Zagora. So he comes with us. The dunes are unimpressive, despite the Tuareg encampment nearby, so we press on to M’Hamid

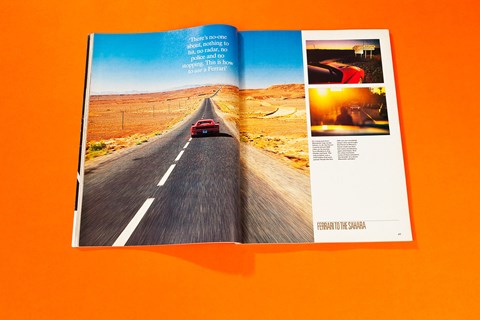

We climb from a plain to another ridge of mountains, only to be confronted by another dish of land. In the middle of it I stop and get out of the car, to take it in. The silence is near absolute. I hear a fly, and the ticking metal of the hot Ferrari, but nothing else. The sky is enormous, the plain completely bounded by mountains whose purples, reds and greys can be made out through the haze.

Stepping back into the car, I push hard to catch the others. The road is single track, but you can see for miles. It crests another ridge, from where it ribbons across the next valley, and arrow-straight path broken by three or four bends. Within minutes, the Ferrari has howled its way to the other side in an unfettered blaze of consumptive excess.

There’s no-one about, nothing to hit but the gravel at the road’s edge and the rev limiter. There’s no radar, no police and no stopping. This is how to use a Ferrari.

M’Hamid is an uninteresting town notable for kids extremely interested in relieving tourists of pens, money and anything else they can proffer. We negotiate a sandy back alley, a couple of kids riding shotgun on the 512’s rear wings, and reach the end of the road, the desert’s edge.

The surface is flat, a baked crust littered with black shards of rock. It may be winter, but you can almost see the heat. It is actually only 26deg C, but it can reach 54. Beyond here lie thousands of miles of desolation.

But we must turn back. We decide to give Mohamed a ride in the Ferrari. He hasn’t been in one before. Nor has he been in a plane, a train or a car travelling faster than 60mph. I tell him to signal if we’re going too fast. When we hit the ribbon-straight stretch of road again I wind the 512 out to a thundering 125mph in third before braking hard for an apparently pointless right-hand bend.

Mohamed says nothing, although he seems wide-eyed and a little tense in the shoulders. The next straight is longer. The engine trumpets its double-bass backbeat as I sink the throttle again and the tacho needle advances relentlessly. Nearly 140mph. The road seems a little narrow for anything more, and in any case, I don’t want Mohamed to think I’m a sadist. He’s already suspiciously silent.

Before we drop him off, he insists that we visit his carpet shop to meet his brother and have some tea. (Are you surprised?) In 20 minutes a dozen carpets litter the floor. In 40 minutes Mohamed’s brother is one carpet lighter and I have an addition for my living room that I hadn’t quite expected to buy. In 50 minutes we bid our farewells, and notice a beige Peugeot 205 diesel outside the shop. Still, it has been quite a day for Mohamed. He’s going to appear in a magazine, he’s travelled seriously fast, and he’s £230 better off now that I’ve bought a rug.

The next day, we head east for Er Rachidia via the towering Todra gorge, whose magnificence is only slightly undermined by fleets of German camper vans. In Er Rachidia we must refuel before striking south for Erg Chebbi. Which is where we have a momentary panic. Because there is no unleaded petrol in Er Rachidia. Nor is there much unleaded petrol in our tanks. Not enough to get north, to Fes. And not enough to go back to where we’ve just been.

Instead, there is Abdoul Oudai, who springs like a genie from the dark. ‘Unleaded?’ he enquires from the gloom of the hotel car park in which we’re retired to confer. Abdoul is a guide, but it takes him a while to persuade us that there’s unleaded further south, in Erfoud. ‘I’m one thousand percent confident – keep my identity card until we get there as proof.’ We do, although it’s hard to see what help this will be if there’s no petrol.

Abdoul also offers to take us out to a hotel at the desert’s edge, where we can watch the sunrise. He takes a look under the Ferrari, reckons it has the ground clearance to cope with the sandy piste south, and leaves us feeling that we have no alternative. And we haven’t.

An hour later, we’re refuelling at Erfoud, excitement rising. We pass the last house in town, and bump onto the piste. Which is where you came in, if you remember, and where we head out into the dusty wilderness. An hour later we see the single light of the Yasmina hotel. Inside this modest single-story building are a young, multi-lingual staff, an American lady dressed as a Moroccan and her Spanish friend. Soon we’re drinking Cokes, listening to drums played by the staff, explaining our mission. It’s not hard to feel adventurous.

We’re up at 5.15 the next morning, to watch the sun ignite the sky. The scene is magnificent, all the more so for the incongruity of the Ferrari. In one direction are rolling dunes that would do Hollywood proud. In the other is a vast plain, bounded by the pale purple wall of the anti-Atlas hundreds of miles away. Right outside the hotel is an oasis, complete with palm tree. The scene may be a visual cliché, but I’d defy you not to be awe-struck.

On a distant dune we momentarily hear the engines of an advance party of tourists. They’re in Land Rovers, which makes us all the more impressed by the Ferrari: it has behaved impeccably despite being showered in dust, belted at high speed, and repeatedly driven over rough roads. At the end of the trip it will have completed 4700 miles and, once cleaned, will bear no evidence of its adventure apart from a few stone chips.

Yet its finest moment occurs not at 150mph, but at 5mph. Abdoul’s return route to civilisation turns out to involve crossing a river. It’s a dry river, which is handy, because the bridge got washed away during the last rains. Abdoul hops out to clear rocks and guide the Ferrari down. Thank goodness Antonio Ghini can’t see us now. It’s bumpy, but the Ferrari edges uncomplainingly into the river bed – there isn’t a rattle or creak from it – where we pick a path between boulders. Climbing the far bank isn’t hard until the last stretch, where we have to turn and power through a drift of sand.

The Ferrari kicks up a cloud just as we spot a white, Swiss-registered Merc G-Wagen edging gingerly over the bank. We pull over to let it through and marvel at its occupants’ amazement. Four-wheel drive? Pah, who needs it?