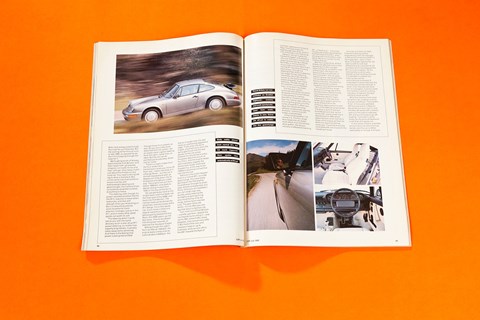

► Russell Bulgin on the Porsche 911

► Classic column from July 1989

► Can it possibly live up to the hype?

I have a natural defence mechanism. If you tell me that something is really, really good, I’ll listen. But if a whole crowd of people keep banging on and on about the virtues of some peripheral sliver of popular culture, then I’ll instinctively start to wonder.

It is for this reason that I have never owned a Pink Floyd album, seen Crocodile Dundee or previously driven a Porsche 911. Try to oversell something to me and the shutters come down. Thanks, but no thanks. I have worked for magazines where the office meritocracy could be quickly established by checking who was taking the road-test 911 home for the weekend. A boss of mine drove a 911 which he juggled deftly between himself and his deputy: us peons used occasionally to see the thing ticking quietly while cooling down in the car park.

I asked him once what was so great about the 911. I expected him to rabbit on about the engine’s response, or the steering feel, or the bullet-hard finish of the thing. He said that it was a four-wheel aphrodisiac.

At that moment I had the inspiration for one of those truly terrible car stickers that you see plastered on the rear windows of Austin 1300GTs. No longer would they read ‘My Other Car Is a Porsche’. ‘Pillocks drive Porsches, too’ seemed succinct enough.

I’ve read the Paul Frère Porsche books, know the car’s history by rote, but never wiggled behind the wheel and given one a hard time through a four-hundred-mile day. Until now. Until the arrival of something called a Porsche 911 Carrera with Sport Equipment.

The Sport Equipment in question consists of four stiff shockers to jiggle the urban ride, plus a front bib and rear toast rack spoiler which kill the 911’s fleshy curves stone-dead. For these nailed-on knick-knacks Porsche will relieve you of £1300 over the car’s £38,000 base price. That detail, hidden in the small print, tells you a lot about the 911, 1989 style.

What do you notice first? The seats are terrific, biting softly into the small of your back: they’re big, too. The car’s size is right: the 911 is small, wieldy. Visibility is superb. No manufacturer today would consider building a sports car with windscreen pillars so close to the vertical, and no manufacturer today would produce a sports car which allows you to position all four corners to the last half-inch.

The Bosch Motronic engine management system kicks in with a little bark just as the motor catches, immediately sounding aggressive and terribly alive.

Pressing the clutch requires an effort close to that needed to persuade a family box to panic stop. This, you think, is Porsche bloody-mindedness. A hundred miles later you’ve discovered that the heavy pedal action allows you just to kiss the clutch on upshifts, making them faster, smoother and more satisfying. It’s a technique you soon pick up.

If you’re tall, you find that your left leg gets sandwiched between the steering wheel rim — which is set too low, as on the 944 — and the gear-lever in fifth gear. Refer to the price-list — which seems to act as a mantra in times of crisis for Porsche owners — and for just over £100 you can have the steering wheel hub extended and the gearlever shortened. (Real Porsche fetishists probably think a bruised calf is a badge of honour. Or perhaps Porsche Design produces a titanium and Kevlar athletic support for just such eventualities.)

The engine, all 3.2 litres and 231bhp of it, is brilliant. It’s noisy: relentless, strident, slightly abrasive-sounding and utterly, compellingly wonderful. This is not the lazy, back-in-the-USA backbeat of a V8, but a dry, brisk whirr that gives the 911 an edgy, tense central nervous system.

And the power comes on strong. There’s a dimple in the curve at 3000rpm where it really begins to load and then, at 5000rpm, the noise harshens to sound like a Hoover on hallucinogenics and the 911 sizzles.

You can blip the throttle on a double-declutch down-change and make the tacho needle dart up by just 200rpm. Or you can simply bury your foot and watch the revs scream: the 911 is that flexible, that well sorted. The power delivery confirms that this is a big, boxer six — but its rev-happy nature makes it feel, when you’re pressing on, like a much smaller-capacity, high-precision engine.

The steering is direct, positive and superbly accurate on turn in. But having read 911 road tests since about the time that my voice dropped an octave, I expected more.

All that stuff about the wheel writhing in your palms and communicating everything, set my expectations too high. There is, I think, a case for suggesting that the 911’s steering tries to be so informative that it ends up supplying data which is irrelevant: kickback over ruts can be fierce.

And — this was a surprise, too — I found the 911 to be a very physical car to drive. I expected lightness, delicacy and finesse but was rewarded instead a machine that requires heft and shove. From the clutch, the stupendous brakes which have perfect front-rear balance, the shift and the steering.

So what you have in the Porsche 911, then, is an agglomeration of components that are either excellent or verging on excellence: engine, gearbox, steering, brakes, seats. Very little of the 911’s dreadful, though the switchgear suggests that the Porsche interior design team failed their ergonomics finals at Stuttgart University.

It took me 300 miles to work out how to open the sunroof — the rocker switch is under the dashboard’s bottom lip — and a further couple of hours’ driving to figure how to flip the electric mirror control from left door to right. The main heater control is located between the seats, and the vent slides are concealed by the south-west quadrant of the steering wheel rim.

When you’ve finally figured it out, heating and ventilation are lousy, anyway: crack open a fresh-air chip-cutter and interior noise swooshes up. It’s just like a Renault 4.

Best of all is the rear window wash/wipe. I could get it to wipe, but not wash. I gave in, and consulted the handbook. There is no rear wash on the 911. A rear wipe without a wash is about as useful as nitrous-oxide injection on a Reliant Rialto.

Where the 911 and I fall out of bed is in its overall dynamics. Everybody knows that backing off in the middle of a fast corner invites trouble in a 911. Exiting backwards-through-the-hedge kind of trouble.

But have you ever tried not doing it? The first law of hot hatch driving is that if you are in deep doo-doo — cornering too fast, too late, too raggedly — you don’t even have to think about it. Just lift off and let careful chassis development and sticky tyres haul you back into line.

The 911 doesn’t work like that. And this is where I get stroppy with all the 911 bores. They say that learning to use the car, to tame its waywardness, is the very essence of driving a 911. A driving experience no car can come close to: your reward, if you like, for putting up with the 911’s flaw is that it gives you an overall responsiveness no other sports car can match.

That, I’m afraid, is what we young people refer to as absolute bollocks. I lifted off in the middle of a roundabout and the 911 flicked its tail out. I caught it. Just.

What you end up doing, of course, is changing your driving style so that you always take corners in such a way as to be in a position to squeeze on an eighth of an inch of throttle if the topography gets bitchy. That way you’re safe. And if you use the 911 on summer Saturdays, or for aimless naffing about — which misses the point in a car that is so obviously intended to give years of faithful service — you can live with this truculence.

So I enjoyed the 911 in the dry — but I almost felt ashamed about it, blatting along B-roads, knowing that if I make a mistake in judging a bend I could quite easily convert this Porsche into a pile of galvanised scrap.

That was the background niggle as it started to rain. And on greasy roads the 911 shows its age. The steering is too light, the front end skates around and the glorious moment of transition from early understeer to mid-corner neutral — the point at which the 911 hype makes perfect sense on dry asphalt — gets blurred and fumbly. When it rains, the 911 turns so-so and backroads journey times lengthen.

I was brought up on Golf GTIs and Peugeot 205s. I gravitated towards Audi’s Quattro and the Lancia Delta Integrale — the 911 remains an anachronism to me. I think, given time, I could construct an analogy that says the Integrale is the 911 of today: as Volkswagen begat Porsche, so Lancia took the humble Delta and infused it with hormones and steroids so it became less a mere car, more The Incredible Hulk, and peeved with it. The Delta Integrale transcended its origins and became a serious performance car. Exactly as happened to the 911 from the late ’80s onwards.

Give me a winding B-road route and a 911 and, if it’s dry, I’ll go quickly in it. Let me tackle the same course in an Integrale and I would be, I’ll wager, no slower. But the Integrale would want to help me — through its grip, its neutrality and fidelity — when the going got tough. The 911 would try to stab me in the back if I couldn’t give it the attention it craves.

My natural defence mechanism goes into a state of high alert in a Porsche 911. So much so that I can’t enjoy it fully.

What I want is a car with Porsche build-quality, afterburners on acceleration, pin-sharp handling and a cornering limit I might only discover if I had a free afternoon on the Silverstone Grand Prix circuit.

Instead, I’ll take a Porsche 944 Turbo. Which is, of course, the Porsche that nobody tries to oversell — and leave the 911 to the real men. Men with something to prove, if only to themselves.