He was the right build for a fighter pilot, or a scrum half, and looked younger than his years. Eyes that had scanned the skies from the cockpit of a Hawker Hurricane, half a century before, glinted in Air Vice-Marshal Harold Bird-Wilson’s tanned and smiling face. ‘Birdy’ autographed my Battle of Britain book and recalled being shot down by the Messerschmitt Bf109E of cigar-smoking Adolf Galland, one of the Luftwaffe’s greatest aces.

He introduced me to John ‘Cat’s Eyes’ Cunningham, Britain’s most famous night fighter pilot, then asked ‘Fred’ to add his signature to my collection. Fred, who had also been a Hurricane pilot during the battle, remained in the Royal Air Force until 1973. By then he was Air Chief Marshal Sir Frederick Rosier, the last Commander-in-Chief of Fighter Command.

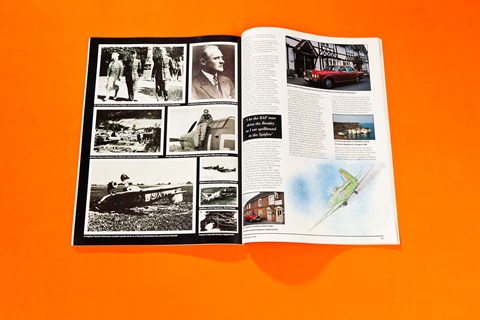

Fred, Cat’s Eyes and Birdy were just a few of the modest old heroes who were on a parade for the opening of the special Battle of Britain exhibition at the RAF Museum in Hendon, a stone’s throw from the London end of the M1. Meeting them was the grand finale to a five-day, 1500-mile odyssey at the wheel of a Bentley Mulsanne S, undertaken to mark the 50th anniversary of the RAF’s epoch-making clash with the Luftwaffe.

There were several good reasons for choosing the £82,371 Bentley. For a start, whatever car was used had to be as quintessentially British as roast beef and cricket on the village green. Bentleys are made by Rolls-Royce Motor Cars in Crewe. The factory was built in 1938-39 to manufacture Rolls-Royce Merlin engines for Spitfires and Hurricanes. The Spitfire’s designer, Reginald Joseph Mitchell had a Rolls-Royce car. Jeffrey Quill’s highly commended Spitfire: A Test Pilot’s Story contains several affectionate references to ‘my old 3.0-litre Bentley’.

Billy Fiske, a young fighter pilot commemorated in the crypt of St Paul’s Cathedral, London, thundered along southern England’s sun-baked roads in a supercharged Bentley, complete with leather bonnet straps and worthy of Bulldog Drummond, Fiske was one of several Americans who volunteered for the RAF more than a year before Uncle Sam joined in the struggle. I was also reminded, while wondering what car would be most appropriate for this once-in-a-lifetime exercise, that Fighter Command’s headquarters, on high ground in the leafy London suburb of Stanmore, had been an 18th-century mansion called…Bentley Priory. That was the nerve centre from which Air Chief Marshall Sir Hugh ‘Stuff’ Dowding directed the prolonged aerial battle.

I recalled the background to the struggle that inspired some of Churchill’s most spine-tingling oratory while waiting for the red Mulsanne to appear outside the Crewe factory’s impressive new reception hall.

From the British viewpoint, the Second World War started on 3 September 1939, two days after Germany unleashed its blitzkrieg – ‘lightning war’ – assault on Poland. In the west, the so-called Phoney War, the lull before the storm, lasted until 10 May 1940. Eleven days later, the first of the panzers that had raced across France at astonishing speed reached the English Channel. Operation Dynamo, which plucked 338,226 British and French troops from Dunkirk’s blood-stained beaches, started on 26 May.

Dowding, despite immense political pressure, eventually refused to send more fighters to France, where they would be sacrificed on the funeral pyre of a lost cause. He stated his case in what has been described as the most famous letter in the RAF’s history. After reminding the Air Ministry that 52 fighter squadrons had long been considered essential to defend Britain, and pointing out that the number had tumbled to 36, he said: ‘If the Home Defence Force is drained away in desperate attempts to remedy the situation in France, defeat in France will involve the final, complete and irremediable defeat of this country.’

France gave up on the struggle on 21 June. Just over a week later, Hitler ordered his commanders to prepare detailed plans for the invasion of Britain, an enterprise for which control of the air was deemed essential. Britain now stood alone, in a position of unprecedented peril, awaiting the full fury of Reichsmarschall Hermann Goering’s cock-a-hoop Luftwaffe.

According to Richard Hough and Denis Richards, whose Battle of Britain: The Jubilee History is required reading, the air fleets charged with bringing about the RAF’s demise mustered about 1260 long-range bombers – Junkers 88s, Heinkel 111s and Dornier 17s – plus 317 of the screaming Junkers 87 dive-bombers that had proved so effective over mainland Europe. Messerschmitt Bf109Es, powered by a Daimler-Benz V12 whose assets included a direct fuel-injection system, accounted for most of the air fleets’ 1089 fighters. Twin-engined Messerschmitt 110s made up the balance.

Hurricanes outnumbered Spitfires by almost two to one in the home team’s line-up. Figures quoted by the RAF Museum are 347 to 199. Bristol Blenheims, Boulton Paul Defiants, and a flight of Gloster Gladiator biplanes, raised the total number of Dowding’s fighting-fit aircraft to 640. No wonder Churchill’s famous tribute – ‘Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few’ – came to mind as rather more than two tons of Bentley Mulsanne whispered away from its Cheshire birthplace, en route for Stoke-on-Trent.

Half a century earlier, Rolls-Royce’s supercharged Merlin V12 had produced 1030bhp from 27 litres. That gave the Mk1 Hurricane a 324mph top speed. The early Spitfire was good for 350 in level flight and climbed to 20,000ft in just over nine minutes. The myth about the power of today’s Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars not being revealed is kept alive by writers who should know better.

Thanks to European markets, which insist that ‘adequate’ does not constitute sufficient information, it should be common knowledge that the Mulsanne’s naturally aspirated, 6.7-litre V8 develops 222bhp at a genteel 4200rpm. Some 330lb ft of torque is generated 2700 revs lower down the scale. Performance figures? My stopwatch credited this heavy, square-shouldered status symbol with reaching the mile-a-minute mark in 9.7 seconds. The maximum, which I didn’t check, must be a little over 120. The speedometer was a paragon of precision.

Why was Stoke-on-Trent my first target? Because it was here that Reginald ‘Spitfire’ Mitchell, a schoolmaster’s son, was born in 1895. A section of the City Museum and Art Gallery in Bethesda Street is dedicated to the engineer who became Supermarine’s chief designer at the age of 24, and died of cancer just 18 years later.

Wonderfully evocative photographs of Mitchell, and the aircraft he masterminded, overlook a Spitfire LFXVI that was delivered to 667 Squadron in 1945. Fifty-four years have passed since the prototype’s maiden flight, but the Spitfire, in my judgement, remains the most graceful and beautifully proportioned of all aeroplanes. In a corner of the Spitfire Gallery stands a Merlin, parts of which have been removed to reveal such details as four valves to each 2.25-litre cylinder. An excellent power-to-weight ratio was one of the most outstanding characteristics of an engine that was eventually modified to belt out as much as 2640bhp.

Two-level air-conditioning soothed and susurrated as the Bentley inched through narrow streets, solid with slow-moving traffic, then made up for lost time on the road to Derby. My destination was the Rolls-Royce aero-engine company’s headquarters in Nightingale Road. Here, in the Merlin’s birthplace, light streams through a window whose stained glass depicts a young RAF pilot. The inscription reads: ‘This window commemorates the pilots of the Royal Air Force who in the Battle of Britain turned the work of our hands into the salvation of our country.’

Quiet main roads and free-flowing motorways, cruised at a discreet and theoretically fuel-efficient 80mph, took the Bentley to Southampton by the way of Middle Wallop, in rural Hampshire. This most euphonious of 1940’s fighter bases stands amid fields that roll gently down to thatched cottages clustered around olde worlde pubs and medieval churches. The sky above these idyllic villages was ripped apart, time and again, when Goering’s bombers attempted to defeat Fighter Command by wiping Middle Wallop, and the rest of the front-line aerodromes, off the map. Middle Wallop is now shared by the army flying corps and the Museum of Army Flying.

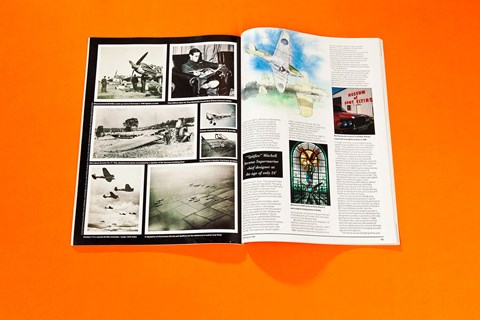

Four o’clock found the red Bentley parked outside Southampton’s Hall of Aviation, which is close to the Supermarine factory’s site. Links with Mitchell include a Spitfire MkXXIV powered by Rolls-Royce’s 36.7-litre, 2350bhp Griffon. But the collection’s most remarkable aircraft is one of two Supermarine S6 seaplanes designed to contest, successfully, the very prestigious Schneider Trophy in 1929. Two years later, a development of that astonishingly sleek aircraft raised the world air-speed record to almost 410mph. Lessons learned from the seaplanes were applied to the Spitfire.

The first of almost 23,000 Spitfires and Seafires flew from what is now Southampton’s airport at Eastleigh. In the passenger terminal, a plaque unveiled by Mitchell’s son gives the date as 5 March 1936. Jeffrey Quill is convinced that the maiden flight took place a week later. Such quibbles concerned me less than the fact that the Bentley’s fuel warning light was on after only 266 quite sedate miles.

Just over 18 gallons were needed to brim the tank before visiting Tangmere. No fewer than 124 gallons had sloshed into the Mulsanne by the end of the trip. The cost factor speaks for itself. Less obvious, perhaps, is the amount of time spent catering for a thirst worthy of Gargantua and Pantagruel.

A small aviation museum occupies one corner of Tangmere, an airfield that was bombed on 16 August 1940 by Ju87s that dived almost vertically from 12,000ft. Anti-aircraft guns held their fire rather than risk hitting the Hurricanes that were taking off the Stukas as they came down, sirens wailing. Billy Fiske, the Bentley man, died that day. Watching the sun set from what remains of Tangmere’s control tower, I said a prayer for all the foreign pilots who contributed so much to the RAF’s strength. They included 145 Poles and 87 Czechs.

Early next morning another link between automobiles and aircraft was forged during a brief stop at Brooklands, between the Surrey towns of Byfleet and Weybridge. Opened in 1907, and now the home of a motoring and aviation museum, Brooklands was the world’s first made-to-measure track for car racing. In 1935, Oliver Bertram and the Barnato Hassan Special, based on an 8.0-litre Bentley, lapped the circuit at 142.6mph.

It was from Brooklands, which incorporated an airfield, that the first Hurricane made its maiden flight on 6th November 1935. Designed by Sydney Camm, the eldest of a carpenter’s dozen children, the Hurricane shared the Spitfire’s armament as well as its engine. Each wing concealed four Browning 0.303in machine guns fed by a total of 2600 shells. The guns were general set for their fire to converge at a mere 250 yards. Accurate shooting was essential, because there was rarely time for more than a two-second burst. But the pressure on Fighter Command became so great that many pilots had never fired a shot until they went into action for the first time.

Biggin Hill, only 15 miles south-east of London’s heart, played a key role in the capital’s defence. Today, Hurricane and Spitfire replicas flank the entrance to the airfield Chapel of Remembrance, which is open to visitors. The White Hart, down the road in Brasted, was a great favourite with this famous fighter station’s pilots. Many signed the blackboard, which is now in the RAF Museum in Hendon.

There was time to spare for a few more thoughts for the Bentley while driving to Dover beneath skies as clear as they had been for day after day in the summer of 1940. Only a cock-eyed optimist equipped with the most rose-tinted of spectacles would expect a car this long, wide, high and heavy to be a miracle of agility. But gone are the days when Bentley and Rolls were synonymous with such pejoratives as barge-like.

Much less money can buy a low-speed ride that’s significantly quieter and smoother, but the latest suspension – introduced last year for all but the ragtop models – combines with informative steering and Avon Turbosteel tyres, to make the Mulsanne far more of a driver’s car than its predecessors.

Tight corners are best treated with restraint, if only because the seats provide less support than Mrs Thatcher gets from the Beast of Bolsover, but the Bentley sweeps through the more open variety on a surprisingly even keel. The biggest problem, when trying to leapfrog dawdlers on give-and-take roads, is the car’s length.

Another point that came to mind, frequently, was that cars such as this no longer provide features far beyond the aspirations of Mr Average. But the Bentley does command respect. I parked in what may have been the chairman’s slot when visiting Rolls-Royce in Derby, knowing that I wouldn’t be there for more than five minutes. The commissionaire who marched out looked tough enough to breakfast on barbed wire sandwiched between concrete. He said: ‘How can I help you sir?’ not ‘Hey! Get that bloody car out of there!’

Standing on Dover’s white cliffs, I tried to picture the scene on 10 July 1940, when German attacks on a big convoy of merchant ships sparked off a series of furious dogfights. This was later deemed to be the day on which the Battle of Britain started.

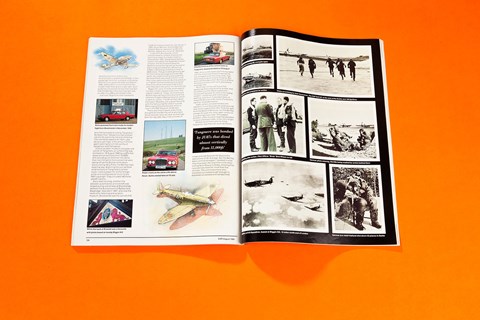

Two months later, Goering and his staff enjoyed a picnic on Cap Gris Nez, 21 miles from Dover, while 1000 aircraft assembled to attack London. The assault’s scale and ferocity were unprecedented. Among those who flew to smite the Luftwaffe’s armada that Saturday were three squadrons from Duxford. Their leader, Douglas Bader, had rejoined the RAF in 1939, eight years after losing both legs when his Bristol Bulldog crashed.

Duxford, on the M11 near Cambridge, was the whispering Mulsanne’s next touchdown point. The airfield where the first squadron to fly Spitfires was based is now part of the Imperial War Museum. I spent a long afternoon that wasn’t half long enough admiring one of the world’s finest collections of military and civil aircraft. Hurricane, Spitfire, Thunderbolt, Messerschmitt 262, Mustang, King-cobra, Mosquito, TSR-2, Super Sabre, B17 Flying Fortress, Sunderland, Comet and Concorde are just a few names plucked from page after page of notes. The room from which operations in the Duxford sector were controlled during the Battle of Britain has been restored, down to such details as a Careless talk costs lives poster.

A top-secret chain of coastal radio stations made a priceless contribution to the efficiency of such ‘ops’ rooms. That’s why the Bentley headed due east from Duxford to Orford, a delightful little Suffolk village whose main street ends in a quay. Four men travelling in two cars, an Armstrong Siddeley and an MG, reached this isolated spot on 13 May 1935. Accompanied by two RAF trucks, laden with equipment, the scientists were there to build Britain’s first experimental radar station. The full story is told in Radar Days by Dr EG ‘Taffy’ Bowen. He recalls relaxing in the Jolly Sailor, where I lingered over an excellent pint before dropping anchor at the Crown and Castle, where Robert Watson Watt and his colleagues spent many a long night talking about what was then called Radio direction Finding.

Squadron Leader Colin Patterson welcomed me to the RAF’s Battle of Britian Memorial Flight and Coningsby, between Boston and Lincoln. He flies the four-engined Lancaster bomber. The flight’s five Spitfires and two Hurricanes, one of which has The Last Of The Many painted on its fuselage, are due to do about 200 displays during this jubilee year. I did a deal with a commanding officer, letting him drive the Bentley while I sat, spellbound, in the narrow cockpit of a Spitfire that flew in the Battle of Britain.

We drove as far north as Flamborough Head, because Yorkshire’s answer to the white cliffs of Dover witnessed an almighty dogfight on 15 August 1940, then spent a night near Lincoln before wafting down the A1 to meet yesterday’s heroes at Hendon. The RAF Museum in general reduced me to a gaping, gasping wide-eyed schoolboy. I could have spent two or three days there, but I wanted to visit Bentley Priory – now the headquarters of the Royal Observer Corps and the RAF’s 11 Group – before returning the Mulsanne.

The last name on my list was Tern Hill, 15 miles south-west of Crewe, which had been a training and operational bade in 1940. On 18 July, a pupil pilot who had just celebrated his 23rd birthday took off in a Harvard, which crashed near Nantwich at 3.15pm. He left a pregnant widow. Her son was born on 23 October, 11 days after Hitler, thwarted by Fighter Command’s resolution, rolled up his invasion plans. Fifty years later, the Pilot Officer’s son was commissioned to roam far and wide across England, gathering Battle of Britain material. He drove a red Bentley Mulsanne.