► Looking back at 60 years of CAR

► From the magazine’s roots in 1962

► Second of our two-part history

This is the second part of Gavin Green’s instalment, the History of CAR. Click here for Part 1

By 1982, CAR was on a roll. Twenty years old, it had graduated from the pioneering rebel of car magazines into the UK’s best-selling enthusiast title. Within a few years, it would overtake What Car? as overall market leader.

‘CAR was perceived as rebellious and different, the blokes who’d tell you the truth, even though there was a whole establishment mechanism out there that wouldn’t,’ says Steve Cropley, who took over as editor from Mel Nichols in autumn 1981. ‘Now we were the leader, we were the de facto establishment. That worried me.’

Yet CAR’s circulation kept booming under Cropley. ‘We deliberately set out, without insulting the opposition, to have a point of view that made everyone else look like they were in a rut and in thrall to their publishers or to the motor industry. The force was with us.’

Cropley, like Tasmanian Nichols, came from an isolated part of Australia, Broken Hill. Like his CAR predecessors, Cropley had newspaper training. He covered the Adelaide stock exchange, before moving to Cairns [in Queensland’s far north] to seek his fortune.

When that proved elusive, he answered an advertisement placed by Peter Robinson, editor of Wheels magazine. They were after a journalist to replace the departing Mel Nichols. ‘I wrote Robbo eight pages of longhand, explaining there wasn’t a typewriter within a 100-mile radius. He answered with an interview date. I told him it would take me a month to get there because I had to rebuild the cylinder head of my old fintail 220 Mercedes and Sydney was 2000 miles away.

‘The drive took a week. I had to travel through bushfires and floods. I bought a suit for the interview in Brisbane on the way. I presented myself in Robbo’s office and his first words were, “Hello mate, when can you start?”I worked there for five and a half years. Robbo taught me everything I know. Respect the reader. Always write as well as you can. Read a lot. Be accurate. Really care about what you do.’

In the summer of 1978, on a press trip to Europe, Cropley asked CAR MD and co-owner Ian Fraser for a job. He loved the CAR environment. ‘Wheels was part of a big publishing company. It had publishers and other shiny bums. I cannot remember, at any time as editor of CAR, being told what to do. That was a huge asset.’

Cropley was king but there were many other key players during those high summer days. Adam Stinson, the son of a judge, succeeded Wendy Harrop as art director and further improved the visuals and expanded the talented band of professional photographers on call. CAR was the first UK motoring title to go to glossy paper, full colour and to perfect binding (square backed) – now all de rigueur among motoring magazines. These were Stinson initiatives.

Cropley had a good relationship with ad manager Margaret-Mary Graham, nicknamed Mumble despite her perfect elocution. ‘She took flak from disaffected advertisers on the chin. It was part of our remit to be different and controversial. She understood that.’

The roll-call of run-ins was long. Honda, Vauxhall, Volkswagen and Volvo – and more – all had spats with CAR during the mid ’80s.

I joined as a staff member in June 1984. I recall MD Fraser marching into the editorial office soon after I arrived and announcing: ‘Good news everybody, we’ve just lost Honda!’ We all cheered and got on with our work, invigorated by our no-compromise stance and our owner’s unequivocal support.

FF was a publishing minnow outgunning the giants. Ian Fraser’s wife Robin personally mailed subscription copies from the family home in Norfolk. Robin did all the accounts. Cheques were handwritten and always sent by return of post, further ingratiating FF to contributors and suppliers. It was a very stimulating environment and success further fuelled creativity.

It was the best of times. Cropley continued Nichols’ formula – exclusive first drives, expansive supercar stories, scoops, industry insights, quirky and clever columnists, ambitious travel stories. Great cars were celebrated; the magazine dripped with enthusiasm and insight. The journalism got tighter. The magazine looked better. Photography got sharper and more imaginative. It got bigger. It became market leader.

Cropley was my mentor. He worked long hours – we all did. He rode a rubbish East German MZ motorcycle – ‘I could leave it anywhere’ – and lived in a characterless modern flat in Osterley right under the Heathrow flight path. He wore the same jumper every day, replacing it only when the holes in the sleeves got uncomfortably big. He owned a Ferrari (a 308GTB) yet did not possess a fridge.

Cropley was my mentor. He worked long hours – we all did. He rode a rubbish East German MZ motorcycle – ‘I could leave it anywhere’ – and lived in a characterless modern flat in Osterley right under the Heathrow flight path. He wore the same jumper every day, replacing it only when the holes in the sleeves got uncomfortably big. He owned a Ferrari (a 308GTB) yet did not possess a fridge.

Cropley surprised us all by resigning in 1985. ‘I thought it was time for CAR to be led by a British bloke who wore a suit and mingled with the industry.’ He left. But his suit-wearing successor did not work out and Cropley – wearing the same jumper – came back.

During his second stint he was instrumental in Fraser and co-owner Andrew Frankl rebuffing the overtures of David E Davis, doyen of American car magazine editors, who wanted to buy a stake in CAR. Davis thought CAR the world’s best motoring magazine and felt it would work in the US where the journalism – although often finely crafted and entertaining – was generally uncritical and the art direction dull. Cropley feared Davis would exert too much editorial influence on CAR. Instead, Davis went ahead on his own and launched Automobile, using many of CAR’s best freelancers and with Mel Nichols as a consultant. In time, the two magazines would become sister publications.

In 1987, Cropley left for good and the fifth Australian editor in a row took over. Like my predecessors, I had a newspaper background: I worked for the Sydney Morning Herald and the Sydney Sun-Herald. I came to Europe in 1980 as a 23-year old to write and travel, and expected to stay about a year. Thirty-two years later, I’m still here.

Unlike my predecessors, I was not a graduate of Wheels magazine. Yet Peter Robinson, Wheels’ legendary editor, did play a part in my CAR entrée. It was 1981: he was in London and was keen to discuss freelance commissions, and suggested we meet at the CAR office.

The offices were exactly as I’d hoped: cramped and untidy, with back issues piled high in the corridors. I met editor Mel Nichols briefly.

That meeting changed my life. I immediately started freelancing for CAR, joined the staff three years later and became editor six years after that first meeting with Nichols.

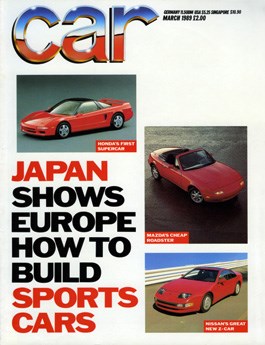

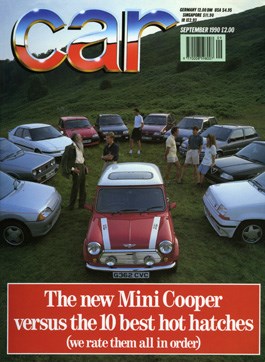

Like all editors who consider their time to have been a success, I was blessed with luck. The late ’80s and early ’90s were halcyon days for driving and motoring. Great supercars were coming thick and fast, the hot hatch was booming and there were no speed cameras to spoil the fun. And the printed magazine’s primacy at delivering information and entertainment had not yet been challenged by the internet. I kept a steady hand on the tiller, for CAR did not need big change.

LJK Setright, George Bishop and Phil Llewellin – introduced as a travel feature writer by Nichols, elevated to a columnist by Cropley – were all writing beautifully. I felt we needed a more youthful contributor to join their ranks and hired Russell Bulgin, who became a good friend and, in the view of some – including current managing editor Greg Fountain – possibly the finest crafter of words CAR ever had.

James May, who would go on to be the most famous son of CAR, was signed later. He replaced dear old George Bishop as a columnist. George was not well and died soon after.

Like my predecessors, I had a hugely gifted art director to make the ideas look good and to help sieve the good editorial initiatives from the bad. Nick Elsden was a protégé of Adam Stinson, in turn trained by Wendy Harrop. The lineage and continuing quality was obvious: the baton in turn passed from Elsden to Peter Allen to Andrew Thomas to today’s art director, Andrew Franklin. Talents, every one.

In the early ’90s, sales kept booming. Young writers – now well-known and widely esteemed motoring journalists – flourished. They included my deputy editor Richard Bremner (a superb ideas man and writer), Paul Horrell (now at Top Gear) and Colin Goodwin (now of Autocar and elsewhere).

Goodwin was one of the instigators of another CAR innovation that began in the early ’90s: the off-beat adventure challenge. My favourite was Edinburgh on a Monkey, in which Bremner and writer Brett Fraser each had £500 (a ‘monkey’ in Cockney rhyming slang) to spend on buying a used car and, still within budget, race each other to Edinburgh. The clock started from the moment I handed them the cash, before they’d bought their cars. Speeding tickets meant disqualification.

We had various multi-discipline challenges in which James May, used car guru James Ruppert, Bremner and others competed against each other in risibly bad secondhand cars.

Goodwin tried to cross the Channel in an amphibious car. Bremner drove a Ferrari Testarossa to the Moroccan sand dunes. We were having fun. It showed in our stories and in our success. Such off-beat features, of course, are now the staple of Top Gear television.

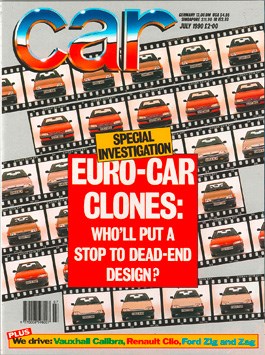

There were many features of which I am proud. Some did not turn out quite as expected. A cover story we did in July 1990, lambasting same-again car design, was apparently influential. It certainly influenced the style of the Ford ‘Frankenstein’ Scorpio, very possibly the ugliest car of the ’90s. Ford told me so. At least it wasn’t same-again.

The daftest decision? Perhaps to list Ferrari’s F40 as one of 1987’s ‘duds’. I justified my decision because the F40 was a Group C-style racer with racing compromises such as sliding Perspex windows, no sound insulation and a race harness. Yet it was never intended to race. ‘Such a stance smacks of insincerity,’ I wrote. Later, of course, I did a long drive in one and loved it.

But the times, they were a-changing. In 1989, tiny FF Publishing sold CAR to News International. We became part of newly formed Murdoch Magazines (along with David E Davis’s Automobile magazine). Fraser and Frankl jointly pocketed £8 million, not a bad return on their £5000 outlay 15 years earlier. Fraser stayed on as MD. Frankl moved to America.

The good times continued. The Murdoch publishers let us get on with it, and improved the magazine’s distribution further boosting circulation. Now that Ian Fraser wasn’t spending his own money, wages and freelance rates went up. Morale was terrific. The magazine’s sales and profitability peaked in mid-1991.

Just after that peak, our ownership changed for the second time in two years. Murdoch was haemorrhaging money from his new satellite TV venture and needed to sell his US and UK magazine divisions to satisfy his banks. There were three serious suitors: Redwood (who then published magazines for the BBC), Emap (a large publishing house best known for its hobby and motorcycle magazines) and the German company Motor Presse, publisher of Auto Motor Und Sport.

Emap bid highest. I think it was £8 million. They wanted to dominate UK motor magazine publishing, just as they did motorcycling. Buying CAR was step one. After their respective failures to secure CAR, BBC Redwood and Motor Presse went ahead with their own magazine ventures. A few years later Top Gear and Complete Car were born. The latter floundered, the former flourished, providing motoring magazine addicts with another choice.

CAR’s once unique formula was now being imitated; British motoring magazines had learnt and followed. One of its key strengths – independent ownership – was no more: it was part of a big publishing house, like all the others. The children of CAR were joining rival publishers, imparting their skills and learnings. Other car magazines were using its star freelance photographers.

Emap bought CAR at its sales pinnacle. That was its misfortune. But it was also CAR’s. ‘They thought it was a mass market title,’ noted Angus MacKenzie, editor from 2002-2004. ‘It wasn’t.’

How could a magazine that was not aimed at the average car buyer, did not do ‘consumer’ tests, was certainly not a buyers’ guide, was outspokenly opinionated rather than remorselessly objective, had a star writer more likely to quote Dante than the RAC, and did not have an everyday familiar ‘brand’, ever hope to be top dog? Yet against all odds, that’s what CAR became. Rather than let it return to its outsider roots, Emap wanted it to stay market leader. Any loss of that position constituted failure.

They chased numbers, as large companies can do. There were redesigns and direction changes, some successful, others not.

One of the most stylish relaunches was under Rob Munro-Hall, formerly editor of Emap’s Motor Cycle News, an ex-Sun journalist and somewhat of an amateur motor sport hero (he lost a little finger while racing at the Isle of Man TT). Munro-Hall, along with his art director Peter Allen, implemented the ‘GQ redesign’ in 1998, where CAR raised the bar – again – for automotive photography. Cars were treated like supermodels, shot in a studio under vibrant lights, creating a distinctive, pioneering feel for covers and features. The fonts, and the cleaned-up logo, were conspicuously similar to contemporary men’s mag GQ, hence the nickname.

Munro-Hall was elevated into the publishing ranks at Emap; today, he’s MD of the specialist division of CAR’s parent company H. Bauer, the family-owned German publisher that bought Emap in 2008. That made Bauer CAR’s seventh owner.

The next editor was Greg Fountain, who brought his considerable journalistic skills to the table and some top quality new writers too, including Alexei Sayle and Anthony ffrench-Constant. Fountain’s on-off love affair with CAR continues: he is currently in his third stint, this time as managing editor.

Angus MacKenzie, who succeeded Fountain as editor, had the perfect qualifications for the job: an Australian who’d edited Wheels. His tenure was cut short when he left for the riches of America to run Motor Trend, around the time a Californian tech company was undertaking its first IPO. That company was Google.

Angus MacKenzie, who succeeded Fountain as editor, had the perfect qualifications for the job: an Australian who’d edited Wheels. His tenure was cut short when he left for the riches of America to run Motor Trend, around the time a Californian tech company was undertaking its first IPO. That company was Google.

The media landscape was changing forever, redrawn by macro trends like the second internet boom, and micro trends like the UK launch of accessible, weekly lads’ mags and the rebirth of Top Gear TV. Emap suits, wrestling with dipping sales at CAR and modifying mag Max Power (the UK’s biggest motoring mag until it was overtaken by Top Gear in 2005) began wondering if a quicker paced, more accessible CAR could better compete with Top Gear and attract youngsters deserting Max.

Editor Jason Barlow, a former Top Gear TV presenter, was tasked with overseeing this radical redesign, which did nothing to stem CAR’s decline. So 12 issues later, CAR veered to the other extreme, with an upmarket, feature-led, expansive and gorgeous redesign. That template, art directed by Andrew Franklin, won the two biggest UK magazine design awards in 2007.

Barlow had positioned CAR precisely where it should be, but he left soon after this 2006 relaunch. The current incumbent, Phil McNamara, took over. His philosophy was to strip out the leftfield men’s lifestyle content, to simply focus on great coverage of great cars. ‘My mission was to bring consistency after the creative storm, and to refocus CAR on its core values. I refused to do a redesign for two years, and when I did I brought back staples like the Good, the Bad and the Ugly data section and Insider industry analysis.’

CAR today reaches more than a million consumers globally a month, through its website, UK edition sold in 32 countries and licensed foreign editions, from China to India, Brazil to Russia. Though UK consumer motoring mags are declining like all print media sectors, there remains an audience for a stylish, well-written and intelligent magazine aimed at informed enthusiasts who prefer paper to pixels.

Today the magazine remains at the centre of a plethora of CAR brand extensions – from this website to our new membership platform and microsite, our social media channels, Youtube videos and outposts such as Apple News+.

If this title’s past has been astonishing, its legacy is assured. ‘CAR brought intelligence, wit and entertainment to motoring magazines,’ notes Angus MacKenzie, the only man to edit major motoring titles in Australia, the UK and the US.

‘It brought a bit of the world of showbiz to the industry. Cars may be made by companies run by engineers and accountants but they sell on emotion. CAR understood that. It has been the template for motoring magazines worldwide. It has been without question the most influential motoring magazine in the world.’

This article originally appeared in the July 2012 issue of CAR magazine and has been updated for our 60th anniversary in September 2022