► Looking back at 60 years of CAR

► From the magazine’s roots in 1962

► First of our two-part history

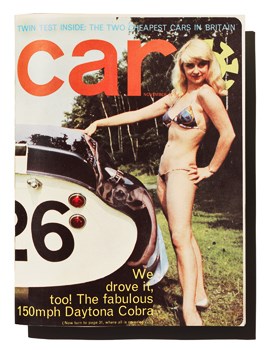

Born 60 years ago this September, Small Car & Mini Owner Incorporating Sporting Driver (as it was catchily titled at first) was very different from the old motoring magazine guard.

Their norm was technically dense stories, ‘frequently written by engineers with all that implies’, remembers early editor Doug Blain. CAR’s approach was different: it invented the motoring magazine template we know today. There were comparison tests (or Giant Tests, as CAR called them), celebrating the victors and lambasting the losers. The UK establishment magazines avoided comparisons; there had to be losers and criticism was considered unsporting. Scoops – unheard of in UK magazines – were introduced to expose secret cars, often years before the motor manufacturers wanted you to see them.

Lifestyle travel, taking great cars on great adventures, was pioneered. Professional journalists or skilled writers crafted the stories rather than enthusiastic amateurs or engineers big on technical ability but low on communication skills. The Italian supercar factories were opened to readers formerly denied access, with evocative stories on the likes of Enzo Ferrari and Ferruccio Lamborghini, and their wonderful machines. CAR romanticised great cars, just as it excoriated dull ones.

It took some time but eventually this became the CAR template. And if the motor industry didn’t like it – and they frequently didn’t – then that was too bad. ‘They complained all the time,’ notes Blain, editor from 1964 to 1971, and the man who really ‘made’ CAR. ‘They withdrew their ads, they stopped us getting hold of test cars. But I always figured that, if we were important enough, they’d come back. And they did.’

Which car makers did CAR offend? ‘Most of them, at one stage or other,’ says Blain.

CAR also inspired most of the best English-speaking motoring journalists working today. ‘They are nearly all children of CAR,’ says Mel Nichols, editor from 1974 to 1981. CAR inspired Clarkson. His outspoken, devil-may-care approach is the CAR formula transferred to the small screen. ‘CAR changed the way it could be done,’ he said in an interview a few years ago.

To understand the roots of CAR, we must go back to early 1962 when publisher Jack Wildbore had an idea for a new motoring title. The Mini was gaining popularity and other small cars were launching or planned. Wildbore wanted a magazine dedicated to them: Small Car & Mini Owner. The Incorporating Sporting Driver addendum widened the appeal and allowed it to add sports cars and motor racing.

Wildbore’s company, Interspan, was based in Fleet Street in central London. George Bishop, who had worked for the publishers of Autocar and Motor, was chosen as first editor. He would go on to become a CAR legend. But not for his editing. He was soon sacked, returning a few years later as a contributor. His column Carte Blanche went on to charm and entertain CAR readers for more than 25 years, thanks to Bishop’s self-deprecatingly simple style and his rich humour, not least his ribald enjoyment of car industry journalistic hospitality.

Bishop frequently wrote as much about the Dom Perignon as the Peugeot. The readers loved it, even if the industry and the journalistic Old Guard did not. It was all part of the multi-flavoured experience that made CAR so very special.

Those early issues of Small Car & Mini Owner used cheap paper like most magazines of the period, and had grainy photos and dodgy printing. But under art director Charles Pocklington the typography was bold and the layouts often mould-breaking. There were splashes of colour peppering the grainy grey. In the second issue, there was a pasting of Britain’s best selling car, the Ford Cortina – ‘a calculated attempt to sell the public ordinariness’.

Such criticism was unknown in the gentlemanly world of 1960s UK motoring magazines, in which market leaders Autocar and Motor invariably saw themselves as part of the motor industry, not critics of it. ‘Their stories were very polite even when testing terrible cars like East German Wartburgs,’ says Blain. ‘They also looked awful. It was obvious that British motoring magazines could be much better.’

Blain, like Bishop, was there at the beginning. He answered an ad in The Times, joined Small Car as assistant editor and took over as editor when Bishop – and his short-lived successor, newspaperman Nigel Lloyd – left. As star columnist LJK Setright later wrote, he ‘gave the magazine its tradition of forthrightness, of independence, of style and of literacy. He gave it its legs and showed it which way to go.’

Blain was also the first in a long line of Australians to edit CAR. Every editor for the next 28 years – if we exclude a brief two-month period in late 1984 – was Australian. Under those five editors – and I was the fifth – CAR’s circulation and influence grew. It became the UK’s biggest selling, and most influential, motoring title.

Quite why Australians, not Britons, forged its identity is difficult to fathom. Blain says that Australian motoring magazines were far more advanced than their UK counterparts in the late ’50s and early ’60s. ‘They had a frank approach and were written in a friendly, approachable way for non-engineers.’ They had comparison tests and scoops. In fact, scoops were such a key ingredient that one journalist in Australia got a job on the GM Holden production line just to sneak photograph a new model.

Blain, born in the island state of Tasmania – like future editor Mel Nichols – had a newspaper background. All CAR’s Australian editors did. This, he says, taught him to write in a structured, economical style, avoiding long sentences, long paragraphs and subsidiary clauses. He put readers first. Ian Fraser, then editor of Wheels magazine – and future editor and proprietor of CAR – used Blain in the late ’50s as a freelance writer in Tasmania, mostly reporting on local motor racing. He offered Blain a job in Sydney as editor of Wheels’ sister magazine Sports Car World. Wheels and Sports Car World became the training grounds for future CAR editors. Ian Fraser, Mel Nichols and Steve Cropley – Blain’s successors – all took the same route.4

Blain travelled to Europe in 1961, booking his passage – ‘the cheapest possible’ – on a returning migrants’ ship to Genoa. Dining on the same table on board was an ambitious young comedian, also keen to try his hand in Europe, called Barry Humphries.

After travelling through Europe in a secondhand Lancia Aurelia, gathering freelance stories for Wheels, Sports Car World and Road & Track in the US, Blain eventually settled in London. ‘I had no money. I had to borrow a fiver from my bank manager. I did anything, even washing dishes. Then I answered the ad in The Times.

‘The idea of producing a magazine for small car and Mini owners was, of course, daft. But it was a job and it was fun. George, who was always eccentric, fell out with Jack Wildbore and was sacked. Eventually, I was offered the editorship. I said yes but told them to change the name. I am a simple man with simple tastes. So I told them to call it simply CAR.’

In 1965, CAR was born.

Blain set about assembling his writing team. He loved the elegant and eccentric prose of Laurence Pomeroy – Pom to his readers. The son of a famous automotive engineer, Pom was technical editor of Motor, where ‘just occasionally a hint of his writing skill and character got into his contributions’, says Blain.

His career at CAR was short. He died when the magazine was young. But his greatest legacy to the magazine was that he inspired LJK Setright, who became CAR’s most distinguished contributor.

Like Pom, Setright would sprinkle his copy with witty epigrams and arcane references. Setright’s circle of influence, however, was even broader than Pom’s. He was as likely to include references to Kipling, Hebrew sages and Virgil, as he was steering geometry and tyre compounds. One column was submitted in Latin. An English translation arrived a few days later.

Like Pom, Setright also gave CAR solid technical foundations. It may have been noisier and more fun than the established car titles. But it also knew what it was talking about.

Blain hired Setright. ‘He wrote to me and asked if he could contribute. We met, got on, and he started writing for us. He filled Pom’s shoes.’

The eccentric Setright was as stand-alone in his dress as he was in his writing. At the time he met Blain, his accessories included a monocle, cane, pipe and an enormous moustache. He looked more Edwardian gentleman than car critic and had the mannerisms and speech to match. Later, when he rediscovered Judaism, he appeared more the Old Testament prophet, replete with flowing beard. He was part of the great eclecticism that was Blain’s CAR.

So was Henry Manney III, a wealthy young American living in Paris who was enjoying a grand life drifting around Europe in exotic cars. He covered Grand Prix racing for CAR, and inspired the magazine to write more about travel. He was also on first-name terms with the heads of the Italian supercar makers. He helped give every CAR reader an entrée into the rarefied Modenese world of romance, power and speed.

Blain also liberated Ronald Barker – ‘Steady’ Barker to his friends – from Autocar, where he’d fought mostly in  vain to lift writing standards. Blain’s dream writing team was being assembled.

vain to lift writing standards. Blain’s dream writing team was being assembled.

Alas, the magazine wasn’t making any money, so Jack Wildbore off-loaded it to a certain Lord Beaumont, who then sold it to the vast National Magazine company run by Marcus Morris, an ex-vicar.

By now Blain had convinced Ian Fraser to come over from Australia to help work on CAR. Fraser took over the editorship in 1971, freeing Blain to concentrate on his other business interests, including renovating old homes and selling antiques. He still wrote a column and features, and was listed as contributing editor. His influence was still profound.

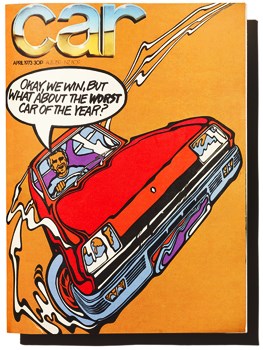

Editor Fraser specialised in ‘big theme’ covers. In the early ’70s there were, after all, more than enough of those to go around, from oil crises to draconian speed limits, from strikes to political disasters. Most affected the car industry, as the nation’s car maker BL began its lengthy death throes. They were angst-ridden times.

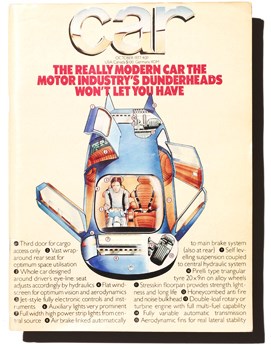

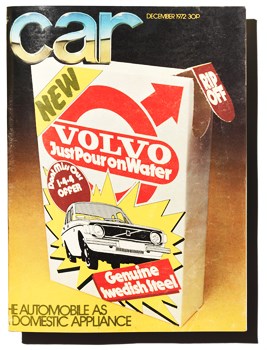

Covers were not so very different from those of The Economist today. Big themes were beautifully illustrated; the stories were thought provoking. Single cover lines – provocative and pithy – made readers think. Like ‘The Automobile as a Domestic Appliance’ on the cover of the December 1972 issue, which berated the trend to automotive blandness (see left), targeting hapless Volvo in particular.

It was a prescient critique. Many cars, particularly Japanese machines – still a few years from popularity – would indeed be everyday consumer goods, mere transport appliances (never mind that they were, like Volvos of that era, frequently of good quality and gave loyal service to owners who weren’t too bothered about driving brio, supple rides or zestful engines). CAR hated most early Japanese cars for their blandness, just as Volvo was regularly criticised. (Although using the collective is risky: CAR was written by opinionated individuals and writers often had contrary views.)

Conversely, Italian and French cars were often celebrated, due to their character, ride, handling, style, verve and driver appeal. If CAR was a touch eccentric, that was fine. It never set out to be the establishment, or reflect mainstream opinion. It never sought to give balanced consumer advice.

The typography was wonderful in the tradition of other great visually mould-breaking British magazines of the ’60s and early ’70s, including Nova and Queen. Intriguing photos mingled with great illustrations. CAR was studied by graphic design schools, their students and practising art editors. One such advocate, Wendy Harrop, another talented Australian but with no interest in cars, visited CAR’s office simply to tell the art staff how much she liked their work. She ended up with a job and later became art director.

She further improved the graphics and, particularly, the photographic standards. She banished enthusiastic amateurs or multi-tasking journalists from taking photos, building up a bank of quality professionals. Much later, she helped to found The World of Interiors and became its creative director.

She further improved the graphics and, particularly, the photographic standards. She banished enthusiastic amateurs or multi-tasking journalists from taking photos, building up a bank of quality professionals. Much later, she helped to found The World of Interiors and became its creative director.

In spring 1973, Mel Nichols followed Blain and Fraser to England, ‘kicked around Europe for a few weeks’ in which he collected an interview with Enzo Ferrari and a ride in a prototype Lamborghini Countach. In the summer he contacted Blain and Fraser.

Nichols freelanced for CAR for a year before taking over as full-time editor in late 1974. He and Wendy Harrop would go on to form a formidable creative partnership, and a marriage.

Meanwhile, major changes were imminent. Marcus Morris told Blain that troubled Nat Mags, whose staple was women’s magazines, was thinking of selling its oddball car title. So Blain, Fraser, advertising manager Andrew Frankl and art director Roger Ames jointly bought the magazine for £5000. Force Four Publishing – later FF Publishing – was born. CAR moved to new offices – ‘the cheapest we could find,’ says Fraser – in Little Britain in the City of London.

‘It was a terrible time economically,’ he recalls. ‘The magazine remained financially dodgy. We often sailed very close to the wind.’ The fearful partners diversified their business, partly by buying an East Anglian pub. Ames left to work for his family’s firm. Blain was getting bored with CAR and with modern cars. He left, leaving Fraser and Frankl in joint control.

It was 1974, and all was not well with CAR. The magazine had certainly caused a stir, it was full of great writing and graphic design, and a promising new editor – Nichols – has just taken up the reins.

Fraser’s three-year editorship had produced many memorable issues. But his irreverent and elaborately illustrated covers, many highly critical of the motor industry, did not necessarily appeal to typical car enthusiasts. Sales were stuck in a rut. It needed another step-change to ignite the magazine from l’enfant terrible of the car publishing world into the market leader. Nichols provided it.

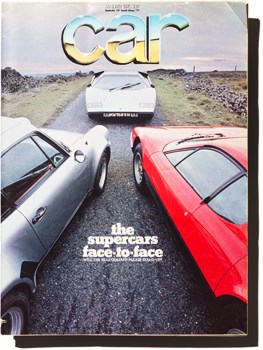

He cleverly tweaked the template. Working with Harrop, he made the great cars even more emotionally engaging. The photography became more gorgeous, more celebratory. Fraser’s quirky doom-mongering covers, clever though they were, were banished. In its place came a relentless wave of extravagant first drives – the faster and redder the car, the better – and news-breaking scoops. If there was a touch more sensationalism, then that was simply another aspect to CAR’s eclecticism. ‘A mate of mine used to call me Mel O’Drama,’ confides Nichols.

The quirky intelligence of Setright, Fraser (who became a columnist) and Bishop shone as brightly as ever. There was more news, more analysis, and a new section – The Good, The Bad and The Ugly – which pithily summed up every car sold in Britain. It began as a monthly regular in CAR – ‘your new car guide to make the salesmen shudder’ – in December 1976.

Nichols was a master of the drive story, putting the reader behind the wheel. Read Nichols at his best and you, the reader, could feel the little jiggle of the Ferrari’s steering wheel, smell the burning oil and brake pads, hear the sizzle of the cooling exhausts, and feel that V12 kick. The supercar had never been celebrated so richly. It certainly had a powerful effect on me, as a kid in Australia.

Nichols was a master of the drive story, putting the reader behind the wheel. Read Nichols at his best and you, the reader, could feel the little jiggle of the Ferrari’s steering wheel, smell the burning oil and brake pads, hear the sizzle of the cooling exhausts, and feel that V12 kick. The supercar had never been celebrated so richly. It certainly had a powerful effect on me, as a kid in Australia.

He also redoubled CAR’s efforts to get the best scoops. Nichols was happy to snoop around test tracks, snapping prototypes, although he often assisted willing professional snappers. (One pro, Mervyn Franklyn, who went on to be a successful car advertising photographer, was a frequent accomplice.)

They were thrown off Millbrook, berated at MIRA and, while snooping around Jaguar’s factory between shifts, lifted the cover of a prototype car. They were hunting for the replacement for the E-type. Nichols found it. He had indeed lifted the covers on the Jaguar XJ-S, the first-ever journalist to see it. But he didn’t know it. ‘Nah. Too ugly,’ he commented, although a few snaps were taken just to be on the safe side. It was one of his few errors of judgement.

Another was to rebuff the initial efforts of an Austrian student who stopped at CAR’s office to enquire about freelance work in 1974. It was gigantic Georg Kacher’s first face-to-face with CAR.

Undeterred Kacher came back the following year. ‘They’d just had a fire in the office and a lot of manuscripts were burnt,’ Georg says. ‘They had six days to deadline. “If you’re worth a pinch of salt, you can write a story now and if it’s any good we’ll run it,” Nichols said. So I sat down and wrote about driving a Peugeot 405 to Iran and selling it. There wasn’t a single photo. I didn’t bring my photos with me. They used illustrations.’

Kacher has contributed to every issue since ‘apart from one or two in the very early days’. When our European editor graduated from university, he ‘enjoyed the work so much I never contemplated doing anything else’.

Under Nichols and art director Harrop, CAR’s circulation boomed. It overtook Autocar and Motor in the late ’70s.

If Blain invented CAR, Nichols made it successful. He redefined the CAR template: evocative drive stories, industry insights, scoops, enthusiasm, withering criticism of dullards, journalistic quality and consistency, always prioritising great photography. ‘On a story or drive, the photography was always the priority. You can stay up all night to write but if you haven’t got the photos, you’re stuck.’

Meanwhile his eventual successor as editor arrived from Australia in October 1978, having also served his apprenticeship on Wheels and Sports Car World. He initially worked for the magazine as chief reporter, under Nichols.

CAR’s success wasn’t over. In fact, it was only just beginning. According to Ian Fraser, Steve Cropley – who took over in 1981 – was ‘the finest editor of the lot’.

This article originally appeared in the July 2012 issue of CAR magazine and has been updated for our 60th anniversary in September 2022. Click to read the concluding part of The Story of CAR