‘A new Metro went by me the other day and, to tell you the truth, I thought it was a Citroen AX. And that upset me, because if I can’t tell them apart then what chance has the average motorist got? After all, I designed the AX.’

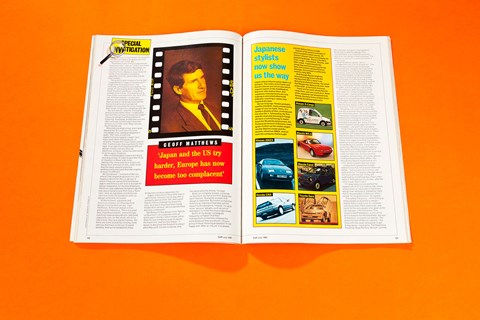

Geoff Matthews is one of Britain’s finest car stylists. His Midlands-based design consultancy, Styling International, employs 45 people. He is the former chief exterior designer at Citroen where, apart from styling the AX, he had a hand in the shape of the new XM – one of the few distinctive-looking new cars on British roads. Before joining Citroen, he designed the Renault Espace, probably the most significant ‘car’ of the ‘80s.

Matthews is one of many experienced designers who – like us – reckon too many new cars look the same. Nowadays, it’s hard to tell a Rover from a Ford, or a Vauxhall from a Renault, never mind the horde of we’ve-seen-it-all-before Japanese saloons, identifiable only by their badges.

The quest to give models a ‘family look’ – supposedly to make a manufacturers range more distinctive – has, ironically, achieved the very reverse. The range of cars sold by Britain’s Big Three – Ford, Vauxhall and Rover – has never looked more similar. This is particularly true of the nose treatment: the ‘face’ of a car. All three makers – as well as number of continental manufacturers – have settled on the droop nose/narrow horizontal grille/shallow tapered headlamps treatment for every model in their range. It’s plainly a shape people like.

But are stylists – and the managing directors who tether them – so devoid of flair that they all have to follow the leader? Clone car design is stifling interest in motoring. Nowadays, brand-new cars are often not even noticed when they first venture out on the road. They look too much like the rest.

Motorists are disgruntled, and it goes beyond the ‘All cars look the same nowadays’ chat, widely propagated in pubs. ‘Old’ cars, sometimes euphemistically tagged ‘classic’ cars, have never been more popular, or valuable. People don’t buy classic cars for their mechanicals they buy them for their style. In an age of unimaginative MFI car design, classic cars are seen as distinctive antiques: attractive alternatives to same-again moderns.

After-market bodykit makers are doing record business. In order to give their Ford or Vauxhall or Rover a bit more individuality, more and more buyers are fitting them with bolt-on bits, never mind that the result usually looks less professionally executed than the original: at least it’s different.

We Europeans – inventors of the car, and still the largest producers of it – are largely to blame for the cul-de-sac in which many car stylists find themselves. Japan and America still look to Europe for design leadership, for the new directions. American and Japanese designers openly talk about trying to give their cars a ‘Euro-look’. And, as Japanese and American cars look more like European ones, so design uniformity increases.

‘At the moment, Japanese and American makers are showing more design initiative than we are,’ says Matthews. American design is now particularly impressive. There is a great deal of professionalism, and some eye catching mass-produced cars. Japanese cars, on the whole, are still a little bland; they lack distinctiveness. Yet there are some wonderful-looking niche vehicles that have come out of Japan recently. And some handsome mass-produced cars have appeared, too. ‘Japan and America have both had an uphill battle. America lost its way after a wonderful period in the ‘50s. And Japan has no history of designing distinctive cars. As a result, they have been trying harder than we have. We Europeans have become complacent.’

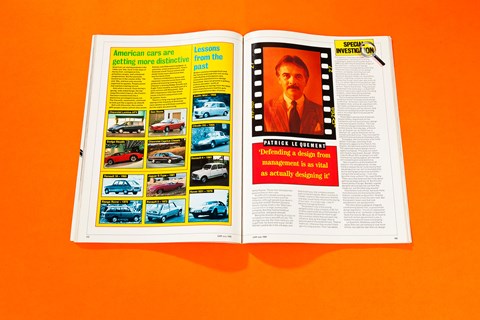

Ask Renault’s new design chief, Patrick Le Quement – an outspoken critic of same-again styling – which maker (other than his own company) gives its stylists freest rein, and he cites Nissan: ‘It leaves its designers the freedom to design what they want. It trusts its stylists. And the result certainly shows,’ he says.

Most car company bosses, contends Le Quement, do not allow their designers such liberties. ‘Everyone accepts that design is important. But some companies think it’s so important that they cannot leave it to the designers. Instead, it’s up to more “serious” people, such as senior managers, to make the crucial decisions.

‘Some of my design colleagues frequently complain that their management sometimes chooses the worst proposal they are shown. I have a policy of never showing proposals I’m not happy with. After all, my job is to please the customer, not senior management. Being able to defend a design from management, is as important as being able to do the design in the first place. The defence of a project is where the battle is won or lost.’

Geoff Matthews agrees senior management has a lot to answer for: ‘The car industry is becoming increasingly cost-conscious, owing to the huge sums now involved in launching a new model. As a result, most managing directors are now finance-based, not product-based. And they’d rather play follow my leader than innovate. It’s safer that way. It may not be lucrative, but – for truly innovative ideas are usually highly profitable. And it may not be better for the industry. But it’s safer, and less likely to lose money.

For instance, after the launch of the Golf, other company bosses knew that concept – radical at the time – was successful , so they got their designers to design a car virtually based on the Golf. The Peugeot 205 was the next big step in the small car class. Other companies, when trying to design a 205 rival, used it as their base. That’s no way to innovate.

‘The phobia all major manufacturers have about market-researching a car has also stifled innovation. Of course, you can understand management wanting some feedback from the general public, before committing hundreds of millions of pounds to a project. But many clinics – where the public pass judgement on new prototypes – just aren’t done properly.

‘It’s pointless asking the general public properly to judge an advanced car. These are people with today’s eyes; what do they know about tomorrow’s cars? They don’t have the vision to see one step ahead. I know from experience that, if you clinic potential small cars buyers in France, many will be Renault 5 owners: if you’re new car looks like a Renault 5, you’re flattering their tastes and they’ll probably like it. They feel more comfortable with a car that looks like their own. Clinics can slow progress. Some clinics, of course, are run more professionally than others. You should only take so much notice of a clinic. Some makers take too much.’

Le Quement agrees that market research now has more power than ever before. ‘Test conditions, in clinics, are quite artificial. The public often get about two hours with the car. If they are surprised by something new, they’ll often reject it. Perhaps two hours later, after the clinic’s over, they’ll like it.

‘I’m absolutely convinced that the biggest risk of all is to take no risk. I have always been an advocate of instinctive design over exhaustive marketing. I told that to the president of Renault, when I joined. To my gratification, he agreed.’

This safety-first policy – of involving as many people as possible in design – means there is less room for visionary individuals than there used to be: less room for the very people who gave us the car industry in the first place. This, reckons Geoff Matthews, is one of the prime reasons for the blandness, the lack of direction, in current car styling: ‘The great old men of the car industry – the ones with the vision and power to get things done – have gone. The Ferdinand Porsches, Enzo Ferraris, William Lyonses, Henry Royces. Those men stamped their personalities on their cars.

It’s difficult for people working within large corporations to exert similar indulgence, although people have done it: Harley Earl and Bill Mitch [General Motors’ styling chiefs in the ‘50s] had a crucial role in a large, bureaucratic company. But they had tremendous personalities, and great strength.

‘Being the director of styling at a big car company is now a very difficult job. The stronger you are, the more likely you are to get fired. Go back and argue, like Bill Mitchell used to in the old days, and they’d sack you. Car company bosses want compliant stylists. When I worked at Citroen, I came to the conclusion that the only way I could really influence the styling of our cars – in a major way – was if I became a managing director.

The problem now is that young designers enter a big company at 20, full of ideas, passionate about the business. It takes a further 20 years or them to get into a position where they can exert any influence. And, by that stage, they’ve become part of the establishment. They’ve had to be: otherwise they wouldn’t have got into a top position. Their raw ideals, their passion, has been distilled.’

Le Quement – formerly of Ford and Volkswagen, before he joined Renault in 1988 (‘just after they finalised the shape of the new Clio’) – reckons car design schools have increased uniformity.

‘There are only a handful of car design schools, worldwide. And they turn out remarkably similar people. When a would-be designer sends me his portfolio, I look for originality: someone who has broken the mould. I don’t see much of that very often, I’m afraid. Most of the portfolios I get, to be frank, could have come from the one person. They are even presented in the same way.’

Le Quement reckons many tutors seem to be moulding students, rather than letting talented students properly express themselves.

The increasing internationalism of the world has further increased world design conformity: ‘American cars look more like European ones; and so do Japanese cars. Our tastes are becoming more similar. There’s nothing you can do about it, and there’s not necessarily anything wrong with it. It’s a fact. But it’s no excuse for bland design.

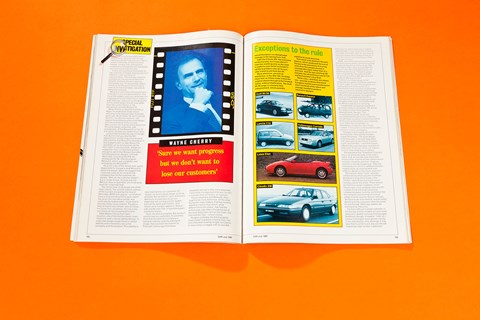

Notes Opel’s styling chief, American Wayne Cherry, responsible for the handsome, but not revolutionary, design of the new Vauxhall Calibra: the loss of national design characteristics is a terrible shame. Not long ago, a French car, an English car, an Italian car, a German car and an American car all looked quite distinctive. They mirrored different national states and backgrounds.

‘Nowadays, the car business is far more global. In Europe, cars have to be designed to appeal to the French, the English, the Germans and the Italians. The Japanese have to design cars to appeal worldwide. This does not mean cars have to look bland, though.’ Cherry cites the Rover SD1 as being a car with international styling appeal, yet one that still looked English and distinctive.

Opel-Vauxhall is at the forefront of research into aerodynamics: its new Calibra cleaves the air more cleanly than any production car. Isn’t it inevitable that, as car styling becomes more scientific – owing to the wind tunnel – it will also become more uniform. No, says Cherry. There are a few hard and fast rules about getting low drag and low lift. But this still leaves plenty of scope. Besides, a good designer should style his car from the inside out, not the other way around,’

Cars tend to look similar, because more manufacturers are following the same fashion, contends Le Quement. ‘And the fashionable look is now the aero look. But that doesn’t mean all cars that look aerodynamic are aerodynamic.’

The other great scapegoat allegedly constraining stylists’ flair, is government design legislation.: ‘It’s not an obstruction to creativity at all,’ contends Le Quement. ‘Quite the reverse. Because we all have to start with certain government rule, it makes the exercise more challenging. ‘

Le Quement, Matthews and Cherry agree that cars are starting to look more and more similar, but add the rider that car design uniformity is not a new phenomenon. Says Cherry: ‘Go to an old car club meeting you’ll see a certain uniformity: similar front end sweeps, window lines, and general proportions. Perhaps it’s just that people are more conscious of it now.’

Cherry also questions the benefit, for the customer, of simply making cars look different, with no follow-on improvements: The average customer probably isn’t as wound up about the benefits of styling idiosyncrasies as enthusiasts are.’ As an example, Cherry mentions the Renault 9, which tried to cater to all national tastes, was awfully bland, but sold well.

Renault is one of the chief perpetrators of the Euro-car clone phenomenon. And it’s all the sadder, when you remember the originality of many of the French maker’s past offerings: cars such as the Renault 4 (a five-seater estate, shorter and lighter than the current Fiesta) or the wonderfully versatile Renault 16.

When Patrick Le Quement joined La Regie, he made bold noises about returning to the halcyon days of that sired such cars. He won’t criticise the Clio – for obvious reasons – yet, despite the professionalism of the design, and the excellence of the car, he must be aware that it has the same design uniformity, and unoriginality, of the Renault 21 or the 19; the same I’ve-seen-you-before Euro face.

Le Quement arrived too late to change that. But he’ll tell you that the R21 replacement ‘will be a big jump forward’, and confirms that Renault are working on a new budget small car that ‘would be just as revolutionary as the Mini, when it was launched’. Always an outspoken man, Le Quement is frank enough to admit that Renault has often followed good car designs, with bad. ‘Soon after launching the R16, we introduced the R6. And the original Renault 5, which was wonderful, was followed by the R9 and R11.’

He is not a fan of the ‘family look’, partly responsible for Europe’s (and Renault’s) dead-end design. When we suggested that corporate looks do far more for the company than for the customer he agrees: ‘After all, the customer doesn’t buy a range of cars, he buys one car.’ Renault, says Le Quement, will move away from the ‘corporate look.’

The ‘family face’ is obviously one of the clear villains. The volume makers, jealous of the success enjoyed by the likes of BMW, Mercedes and Jaguar – all of whom have a long-standing family style which has given the cars an extra cachet, and undoubtedly helped sales – have tried to emulate these luxury makers. Trouble is, they all had to start afresh, and all chose the same look; doubtless, the one every manufacturer found seemed the best.

Adds Wayne Cherry from Opel-Vauxhall, one of the first European makers to seek a family styling identity: ‘A corporate design image shows a certain stability about the company and product. The stability is very important to our customers. Of course, we want to push design as far as possible. But we have to catch as broad a spectrum of customers as we can, especially with our big-volume models, such as the Astra and Cavalier. That means we’re trying to appeal to 18-yearolds and 80-year olds, to business buyers and family buyers.

‘Sure, we want to progress. But we don’t want to lose our customers. If customers think that Vauxhall as a company is losing its stability, radically altering its image, that would be very bad for us.’ That said, Cherry says that future Vauxhalls will look a little more disparate. ‘I also think it’s important that you can tell a Cavalier from a Carlton, at a glance.’

Future Vauxhalls and Renaults, then, ought to be more distinctive. Of the other European mass makers, Fiat has recently adopted a family look which, while different from the others, has had the unfortunate side-effect of making two of the most distinctive cars on the road – the Uno and the Tipo – virtual clones.

Peugeot, probably the first European car maker to present a family face, has one of the best-looking ranges, but seems to have come a cropper with its new 605 executive car, which looks like a slightly upscaled 405. To our mind, this is likely to hurt sales of the 605: after all, why should executive buyers fork out big money for a car that looks no more prestigious than a cheaper vehicle?

BMW, one of the keenest proponents of the family styling theme, similarly has had trouble selling its top-of-the-range 750i. And little wonder, when this £50,000 V12 saloon looks like a £15,000 3-series. As Matthews points out: ‘People buying a Metro like the idea that it has the same face as a Rover 800. But what will the Rover 800 buyer think?’

Ford is now a keen player in the corporate look game, and there seems no let-up in sight. To boot, the company is a keen proponent of the world car, a phenomenon that concerns Le Quement ‘I was at a seminar recently where it was argued that because skyscrapers are now used, and seem poplar, throughout the world, so it should be possible for a manufacturer to sell a single type of car throughout the world. This McDonald’s-On-Wheels approach is worrying.’

Nonetheless, Le Quement predicts a growing variety in car styling. ‘We are on the verge of some really exciting developments’, he says. ‘The miniaturisation trend, which has revolutionised the electronics industry, should allow us to vastly reduce the size of items such as the heaters, thus allowing us to make the cars smaller, or alternatively, make the cabin much roomier. There will be some breakthroughs shortly in vehicle packaging.’

Changes in packaging are far more exciting than mere styling changes, argues Matthews: ‘The great design breakthroughs in the past have been with cars such as the Citroen Traction Avant, and the Mini – cars that looked different because they were engineered differently. That said, I think car makers will put more emphasis on styling.

‘Surveys show that 75 per cent of people buy a car partly because of the way it looks. And, as cars become more similar in terms of their performance and their reliability and their longevity – and this is already happening – then the manufacturers will try to differentiate their models more, by making them look different. Stylists will be more important.’

The trend to more ‘niche’ vehicles – comparatively small volume machines designed to plug small holes in the market – should also put more novel-looking cars on the street. There should be more two-seater roadsters, small leisure vans, multi-purpose vans and off-roaders. Ford of Europe chairman Lindsey Halstead, recently confirmed that his company was looking at a whole range of small-volume ‘leisure’ vehicles: ‘We have to be more flexible, and be better able to give the consumer what he wants,’ he maintained. Other big makers are starting to do the same.

It’s more difficult to predict whether or not the big-volume models will look more distinctive, despite some promising signs/ Matthews, though, is hopeful: ‘After all, I believe that buyers want greater variety, more individuality. And, although it may take them a while to act, big volume car makers do listen to their customers.’