So the Miura is dead. Beset by pollution problems, hemmed in by speed limits, noise restrictions and the ruinous cost of fuel, and finally knocked on the head by the safety lobby in several countries at once, the last of the great extrovert of supercars has gone.

With it, of course, goes a way of life. One could almost say that buried with the Miura is the whole idea of motoring as a heroic hobby, a manly passion, a blood sport, something dangerous to be indulged in purely for kicks. I say ‘almost’ because in fact there will be other Miuras, just as there are already other supercars. But they are different.

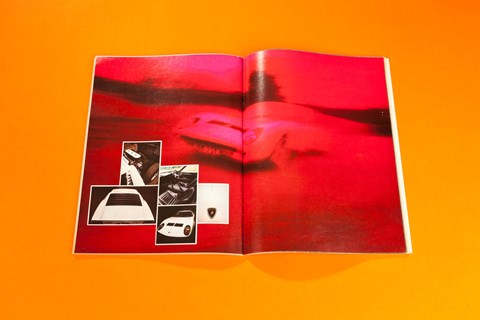

For the Lamborghini Miura was nothing more nor less than a piece of pure, swaggering, extrovert self-indulgence, spectacular to look at, uncomfortable to ride I, difficult to control, ruinously expensive and very, very fast. It was never intended to be anything else than the 20th Century equivalent of the razor-taloned falcon, the lion-hearted hunter, the favourite suit of damascened Swabian jousting armour, the private bodyguard of highly trained Russian mercenaries, the rich man’s compensation for all the duelling pistols, thigh boots, cocked hats, swordsticks and other virility symbols of a bygone age.

The Miura started life, typically, as a publicity stunt. Cavalierre Feruccio Lamborghini, tractor magnate turned sports car manufacturer, needed something to boost the profile of his small but successful enterprise at Sant’Agata Bolognese. Most of all, he needed a new body for his bread and butter luxury GT line, the 350GT and 400GT/2+2, but the only was he could get that was by persuading top coachbuilder Nuccio Bertone to take an interest in his enterprise. Bertone was keen to sign a contract with one of the more exotic marques in order to score off his rival Sergio Pinninfarina, who had for years had an exclusive understanding with Ferrari, but he felt that Lamborghini was too new to the game and that to produce just another body for the 350/400 series would be an undignified way to kick off an already risky relationship.

During negotiations, then, it was decided that Bertone’s first production assessment could wait for a year or two until Lamborghini was ready to go ahead either with the six-cylinder small car which he had set his heart on – the spectacular but abortive all-glass Marzai – or the full four-seater luxury saloon, later to emerge as the Espada, which was then considered a bit of a long shot. The job of rebodying the 400 series would go to a small firm in Milan in which he had taken a financial interest, having seen the writing on the wall for his original coach-builders Carrozzeria Toruing, but meanwhile there remained the problem of an eye-catching, publicity generating gap-filler for the crucial year or so that would elapse before any of these could be got ready.

It was then that Gianpaolo Dallara, Lamborghini’s chief engineer at the time, had his brainwave. Dallara had left university determined to become a racing car designer. He had had a short but spectacular in the motor industry, and so far his ambition remain unfulfilled. He had already tried hard to convince Lamborghini that a full scale racing programme was essential to the company’s prosperity. As part of his argument he had made a detailed study of the Ford GT40, a potential Le Mans winner which he thought ought to be the mainstay of Lamborghini’s first venture into racing.

This was the basis for his new idea. Why not produce a single prototype to his configuration, let Bertone design a spectacular one-off body for it, and as an additional come-one for the newspapers, hint that anybody who could afford a suitably fantastic asking price might possibly be allowed to have a replica? ‘The fastest, most expensive sports car in the world!’ The Cavalierre could see the headlines, imagine the publicity, almost feel himself shaking the hands of the influential clients he would meet. It was a marvellous idea. He mentioned it to Bertone, who was enthusiastic subject only to seeing the car in chassis form. He gave the go-ahead.

So it was that the Miura appeared, as a naked chassis only and without a word of explanation, at the Turin show in early November 1965. It was little altered from Dallara’s original conception, and it still boasted many of the hallmarks of pure competition design. The radiator, for example, was mounted horizontally over the driver’s toes. There were wide, flat sills to the fabricated sheet steel centre section, and the battery box was part of the stressed structure deep inside the spinal tunnel. There was no room for a spare wheel, or for any luggage. The mechanical components, the four-litre V12 engine with its four chain-driven overhead camshafts, and its four sets of triple-throat downdraught racing carburettors all perched transversely on top of a five speed gearbox, multi-plate clutch and final drive unit so that the whole lot shared the same oil – why, the idea was fantastic. In an economy saloon like the mini it had caused enough trouble, but in a 200mph projectile like this…what did the old man think he was going to do? Break the land speed record? He’d be lucky if the thing held together for long enough to even attempt that.

Meanwhile, Lamborghini said nothing. But Bertone had seen the chassis and been suitably inspired, and the job of designing a body had been given to his head stylist, Giorgetta Giugiaro, who was already in the process of packing his bags and had thus delegated it to his assistant, the youthful Gandini. By the following spring a crude wooden buck had been built and a set of aluminium panels beaten out by hand, and with less than a day to spare the prototype was wheeled out and loaded up for dispatch to Geneva.

Its impact there was tremendous. The hastily conceived body was pretty sketchy in a lot of its details: the carburettors, for instance, still had their bell mouths and there was nothing at all to separate them from the cockpit. However, enough of the original shortcomings of the chassis had been rectified and enough practical solutions worked out in the designs of the package as a while to convince even a critical onlooker of the car’s possibilities as a road-going two-seater. A proper boot, for instance, albeit a small one, had been conceived in the tail, on top of the sinuous exhaust system. The accessibility problem had been neatly solved by making the whole tail section, bootlid and all, hinge about the ends of the fork-like engine and subframe. Engine heat could conceivably escape through the clever verandah-like slats that served instead of a conventional rear window., and the radiator had been moved to a more normal location to make room for the battery and an under-bonnet spare wheel. The car was compact, solid-looking and lower than anything else on the roads. It was officially for sale. Without consulting his engineers or anyone else, Lamborghini opened an order book. By the time the show was over he had sold enough cars to more than justify an initial batch of 10 or 15 examples at an unheard-of price of 75,000 Swiss francs.

Now the soft stuff really hit the fan. Dallara, having given birth to this extraordinary monster, half-racer, half road-burner had saddled himself with the job of making it at least safe and, if possible, sanitary. All that summer he and Bob Wallace, his chief tester, slaved away at the show car, the only prototype, running up mileage to see whether the engine/transmission package was really workable, sorting out take-off points for all the auxiliaries, arranging access and at the same time wrestling with the twin bogeys of cockpit heat and internal noise. A new menace materialised, too: high speed instability. For the aerodynamics of the Bertone body turned out to be less satisfactory than had been apparent from just looking at the design (most of the intakes actually expelled air!), and the flexibility which Dallara hastily worked into the limited-travel suspension to convert it from rock-like competition to some semblance of roadgoing softness had side-effects which were the last thing anybody wanted at 170 miles an hour.

If despondency prevailed at the beginning, by July there was an occasional flickering smile to be seen on Bob’s usually impassive countenance, and when Turin show time came round that autumn the prototype, more or less sorted was actually on call as a customer demonstration car. It was then that I had my first ride in Miura, and what a memorable experience it was…

First, there was the seating position. Some of us have since got used to driving lying down, but as I unfolded myself into that hard an very cramped passenger seat on a wet and windy November day in 1966 I felt like a doomed goldfish about to be hurled out, water and all. My piece of mind was not helped by the fact that the windscreen wipers blades were only about half the size they should have been (‘Make ‘em any longer and they don’t even touch the screen at over the ton,’ observed Bob laconically) and there were no seatbelts. And the noise! Double-thickness glass had been found to give reasonable sound insulation for the production cars, but this one still had just a single sheet of Perspex, so what with the whining racket from the gearbox and final drive (and particularly from the uninsulated water and petrol pumps), the raucous below from the virtually unsilenced exhausts and the relentless sucking and farting cacophony from the carburettors literally three inches from my ears I felt pulverised into virtual insensibility before we had even left the Turin suburbs.

Perhaps this was just as well, for by the time we got to the Autostrada I had achieved sufficient detachment from reality to preserve me from the shock of the Miura’s performance, which otherwise might very well have caused me to pass out. Even today, a 0-100mph acceleration time of 15 seconds is enough to shake any but a hardened competition driver on casual exposure. In 1966 my experience of really fast cars was rather less than it is now and I was simply unprepared for the trauma of being hurled at the horizon with quite such energy. I can still remember my horror at the relentlessness of it. All right, to get that quickly to the ton was pretty wonderful, but those two big hooded dials in front of Bob just wouldn’t stop moving: 120, 130, 140, 150…good grief, was it never going to end? Most of my guts were lying scattered about in the luggage compartment and there was just no way I could get myself back together.

That was the first time. In the intervening years I got to know the Miura well, following its vicissitudes, hearing all those heart-stopping stories about people like Jean-Pierre Beltoise sailing straight off motorway at 170mph-plus, cursing its shortcomings, most particularly the high speed front-end float (cured only by fitting an aerodynamic spoiler lip which was alas illegal in most countries), but also those wipers, the lack of cockpit ventilation, (solution: air conditioning) and the hopeless Fiat Spyder headlamps (no good even with q-i bulbs) while learning to love its shattering performance, its responsiveness, its cornering power and, perhaps above all though often very much against by better judgement its irresistible extrovert character, arising as it did as much from its looks and the way-out colours it was painted as from the adrenalin-stirring noises that continued to find their way, though somewhat abated, into the cramped cockpit.

The last time I drove a Miura was also the occasion on which I introduced your esteemed editor, Ian Fraser to its persuasive charms. We had spent the morning wringing out one of the front-engined Lamborghinis, a Jarama, up the Apennine Mountains. It had been Fraser’s first experience of the marque, and he had been impressed to say the least. Not unnaturally, when the time came for us to take out the latest Miura SV he was curious to know in what way it would be superior to its stablemate. ‘Just wait and see’, I said, apeing bob.

Well, Fraser is a nervous enough passenger at the best of times, and I have got used over the years to his occasional tremulous remarks about the state of the road surface, the weather, or his digestion. This time he said not a single word, and I really believe he lost consciousness for a brief period soon after I started the engine. For if the early Miura was fast and frightening, the SV, with its ultra-wide, low-profile, high hysteresis Pirelli tyres and its revised rear suspension designed to eliminate bump steer and ameliorate the high speed wander, was, though considerably safer, eve faster and not a whit less noisy.

First of all I did a quick turn round the back-doubles to re-familiarise myself with the controls (much of the switchgear had by this time been moved from its original science-fiction location in the roof, and the five-speed gearbox had become a lot more positive though no lighter), hanging the tail out with a will in first and second gears (perfectly safe, thanks to the quick, pin-sharp steering and superb balance, but too much for poor old Frase nonetheless), noting the unfavourable effect of the new tyres on an already marginal ride, and doing a series of fade-provoking stops (they didn’t constitute provocation) on the brand new ventilated discs. Up in the mountains we really let go, sliding through the corners, whooping up and down through the gears, taking her right up to 7000-plus on all the straights, climbing relentlessly on the anchors, revelling in the compactness and extreme responsiveness of a true thoroughbred, so that by the time we came back down again we both had sore necks and I was soaked in sweat, for all the world as if I’d just done the Targa twice over.

Later, choosing a long, sweeping open bend that had recently been resurfaced, we stopped to take some pictures and to check the car’s behaviour at high speeds in such situations (early models had felt pretty odd in really fast sweepers). What happened next summed up, for me, the magic of the Miura, for not only did passing motorists turn and stare, neighbouring peasants glance up from their work and an occasional beast of burden take offence – oh, no. It wasn’t even a matter of somebody, as in England, phoning the police. What happened was that within five minutes, right out there in the depths of the countryside, with very little traffic and hardly a car in sight, let me swear to you and may I drop dead this minute if I tell a lie, within five minutes a positive crowd had collected. Not a hostile gathering, either, but a vibrant, enthusiastic crowd of men and women and kids, smiling and waving and cheering and shouting ‘Viva la Mille Miglia’ and holding up the traffic (truly, I’m not kidding), marking out the best places to turn around, signalling all kinds of real and imaginary hazards, offering gratuitous advice of one sort and another and generally just enjoying it. You heard, Mr Toms – enjoying it. Enjoying the car. Enjoying the Miura. Enjoying a selfish, dangerous, pollution-ridden status symbol that none of us who drove it will ever forget.