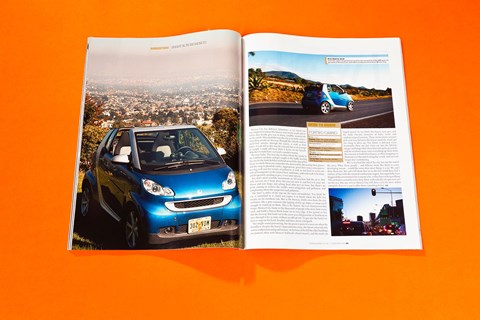

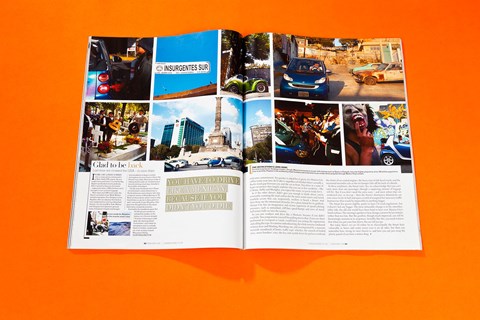

► A global adventure for Europe’s city car

► Smart Fortwo vs sprawling Mexico City

► A travel story from the CAR+ archive

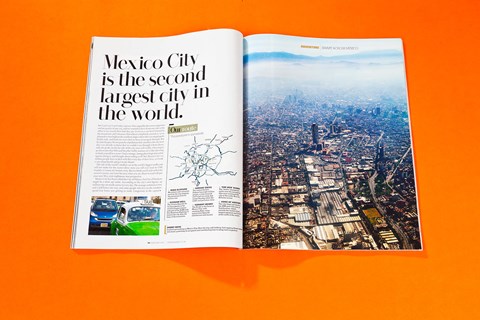

Mexico City is the second largest city in the world. But I can’t see it; not today, anyway. It has arguably the worst congestion and air quality of any city, and we wanted to drive from one side to the other to see exactly how bad they are. The city sits in a vast bowl formed by the mountains and volcanoes that almost completely encircle it, so we planned to start high on the southern slopes where this megalopolis finally ends, and look out over what we have to navigate through. But by 9am the grey-brown poncho of pollution that smothers the city most days was already so dense that we couldn’t see through it from above; only the peaks on the far side of the city were still visible. Choosing to go down into that filth and breathe visibly noxious air is like choosing to dunk yourself in a sewer. I had a strange, strong physiological reaction against doing it, and thought about calling it off. But Mexico City’s 20 million people have to deal with this every day of their lives, so I took a very deep breath and got in my Smart.

The tale of the world’s smallest car in the world’s biggest traffic jam will not make for the raciest drive story you will ever read. It’s more of a horror story. But we think you’ll stick with it for several reasons, not least because it will put your next M25 nightmare into perspective.

Mexico City has been called the City of Palaces, but City of Paralysis might be a more apt name. According to the city’s own figures, 29 million trips are made across it every day. The average commute is two and a half hours one-way, and some people who live on the outskirts spend four hours just getting to work. Congestion in the capital costs the Mexican economy £5 billion each year. Every day, four of the people stuck in those jams will be kidnapped and nearly 100 will be robbed. Every day. And every year, 4000 people will die as a direct result of air pollution, 84% of which is caused by vehicles. And it’s getting worse as 350,000 cars are added annually to the six million already registered here. But why is it so bad in Mexico City? By coincidence, I flew in straight from Tokyo, easily the world’s biggest city. Tokyo’s traffic is bad too, but at least you know that there is an alternative. That city’s public transport network is vast, more punctual than the atomic clock and cleaner than a British hospital ward. You would no more choose your car to cross Tokyo than choose a bicycle to cross the English Channel.

Mexico City is different. It also has a large tube network; with 175 stations and four million passengers each day, it’s the fourth biggest in the world after Moscow, Tokyo and New York, and it costs only 10p regardless of how far you travel. But it services only the eight million who live in the central Distrito Federal, or DF. If you’re one of the 12 million who live beyond it there are no trains. You must come in by road, either in your car or in one of the filthy pesero buses that belch so much black smoke under acceleration that their back end often disappears altogether.

To make matters immeasurably worse, Mexico City has no M25. All ‘through’ traffic gets dumped into the city and has to crawl across it with the commuters. Forget Tokyo; Mexico City is more like Mumbai, a megalopolis whose population has swamped its transport, a place where getting from the edge to the centre seems an endless, hopeless quest.

That explains the congestion. The pollution is caused by the emissions from those six million, often old and sooty cars and buses getting trapped in the geological bowl in which the city sits. Then it is cooked by the fierce sun to produce lethal ground-level ozone. You might still be asking why you should care; you don’t have to sit in these jams, or breathe this air. But the carbon dioxide that simmers off all that stationary traffic warms the entire globe and, ultimately, we all pick up the tab for the human and economic wreckage caused by big jams and bad air. If you’re reading this you probably like cars, but even car fans have to admit that, in some situations, the car creates more problems than it solves.

Of course, you’re not going to fix Mexico City’s public transport overnight, or stop poor Mexicans aspiring to car ownership, or do the same in any big city in the developing world. Smart reckons it has the short-term answer. Build a car expressly for city use that is significantly smaller and less polluting than some of the other options. The Smart feels like a car whose time has come. On the day we drove it across Mexico City, oil prices breached $92 a barrel, which partly explains why Smart is offering the new, second-generation version of its little car for sale in America, and thinks that it will sell enough to move the brand into profit. We couldn’t think of a better test for Europe’s smallest city car than to drive it across the biggest city in the Americas, and the one where it might do the most good.

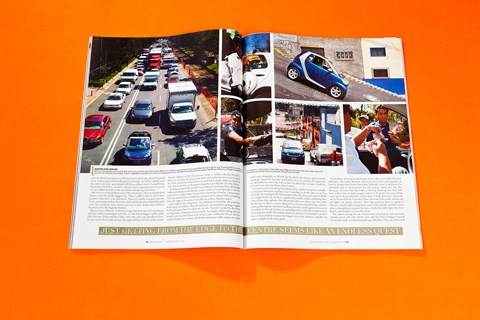

So, the drive. Starting at 9am means we miss the worst of the Mexican rush hour. The words ‘Mexican’ and ‘rush’ aren’t often used together, at least by people who haven’t been here, although ‘hour’ is definitely the minimum unit of measurement for any journey across this city. But Mexicans do rush when the traffic is moving, knowing that they only have a short time to make progress before it all grinds into arse-aching stasis again. So roundabouts can be taken in both directions, slip roads can be reversed down if you don’t fancy the look of the traffic ahead, and red lights are purely optional. Most big junctions have a squad of Mexico’s innumerable, omnipresent police with whistles and dirty white gloves, attempting to organise the chaos. Unlike the traffic lights they have pistols and shotguns, so you obey them.

The vehicles racing you are a bizarre mix of European and American. Ancient green and white Beetle taxis and tiny Chevy-badged Vauxhall Corsas dice with vast American pick-ups and semis. All are driven with utter commitment. No quarter is asked for or given; if a cabbie wants your lane, he’ll take it, regardless of whether there’s actually a Beetle-sized gap between you and the car in front. You drive in a state of hyper-awareness that largely explains why you see so few accidents – like in Rome, Delhi and Shanghai, you expect the worst, so you’re ready for it.

As if the other drivers didn’t give you enough to think about, you’re constantly scanning the road surface for the torso-sized craters and raised manhole covers that can, respectively, swallow or beach a Smart. And then there are the intentional obstacles; for a place famed for its gridlock, Mexico City has an imaginative and vicious repertoire of speed-calming measures, such as unmarked, cliff-face speed-bumps and rows of metal half-tennis balls set into the tarmac.

So you just readjust and drive like a Mexican, because if you didn’t you’d die. You congratulate yourself for pulling moves that, if you saw them performed in say, Leeds, would have you noting the registration and calling the cops. It is intense and exhausting, and conducted in fierce heat and blinding, bleaching sun, accompanied by a constant mariachi soundtrack of horns, traffic cops’ whistles, the screech of locked tyres, street hawkers’ cries, the fizz and crackle from the pylons overhead, the clatter of air-cooled engines, the bassy roar of old diesel trucks and the occasional marimba solo as the tin bumper falls off a Beetle.

In these conditions, the Smart rules. Yes, we acknowledge that you can’t carry more than one passenger (though a surprising amount of luggage will fit). But if you don’t need the extra seats – and most urban trips are conducted one- or two-up – then the Smart’s diminutive dimensions cut your stress levels in half and open a world of marginal but necessary traffic manoeuvres that would be impossible in anything bigger.

The Smart has grown slightly, partly to meet US crash regulations, but it doesn’t feel any bigger. The most noticeable change is in the smoother, softer ride; the old one would have been hard to bear over Mexico City’s harsh surfaces. The steering is quicker so lane changes can now be last-minute, rather than too-late. But the gearbox, though much improved, can still be frustratingly manana in its responses. In traffic like this, you need to know that when you put your foot down, the car will just go.

But today there’s no car I’d rather be in. Occasionally the Smart feels vulnerable as buses and semis tower over it on all sides, but then you remember how strong its steel chassis is, and how you can just swap the plastic panels if you have a minor ding.

It’s odd how context changes your appreciation of a car. In Mexico City the Smart’s cabin air filter, self-locking doors and hill-holder suddenly assume huge importance. But with the heat and smog and crime I could live without the cabriolet roof, and the ‘eyeball’ clock sprouting from the dash only reminds me how much of my life is ticking away in this jam.

There’s no built-in sat-nav, but it turns out we don’t need it. We wanted to see how long it takes to cross the city, and so we took the most direct route. This turns out to be the Avenida de los Insurgentes (‘the Avenue of the Insurgents’) that, at 18 miles long, splits the city and links major routes north and south. You know you’re in the developing world when the streets have names like this, celebrating national dates, events and heroes; we also pass Fifth of May Avenue and Revolution tube station.

Insurgentes is the longest urban avenue in the world but it’s also part of the longest road – the 30,000-mile Pan-American Highway – so, if you want to drive from one end of the Americas to the other, you have to go through the centre of Mexico City. Yes, really.

All human life is in an Insurgentes traffic jam. There is violence; we saw three fistfights in as many days. One was between drunken mariachis but the others blew up after minor prangs, one a full-on dust-up right in the centre of town and in full view of the legions of cops. Mexicans seem a laid-back bunch, but roads this bad could induce road rage in the Dalai Lama. There is sorrow too. We saw one woman weeping gently in the car next to us. We don’t know if the traffic made her cry, but it might easily have done. And there is kindness; a posse of drivers left their cars to attempt to lift one out of the pothole it had fallen into. There is also joy, mostly directed appreciatively at the funny little car we’re driving. Glad to be of amusement.

And there is shopping. Even where Insurgentes broadens out to become a 12-lane highway, the jams are sufficiently static for an army of hawkers to make a good living from captive customers. We’re not just talking about buying a paper or getting your screen cleaned; you can buy actual replacement windscreen wipers in the jams, along with a good selection of other car parts, fags, sweets, drinks, jewellery, model cars (including one of a Smart cabrio), and ukuleles. Don’t know about you, but I always buy my ukuleles in a traffic jam. And there are entertainers; jugglers and puppeteers who have time to go through most of their repertoire before you finally inch forward again.

The exact parameters of Mexico City are debatable, so we timed our run from where the houses start on the south side to where they give way to scrubby countryside on the north. Sixty miles. Driving mostly on ‘freeway’ through the suburbs and on multi-lane arteries through the centre, it took us four hours. Good, but at an average of 15mph I could still have done it faster by bicycle (though I might now be dead).

We were lucky. The next day we drove from the centre to the northern outskirts and got caught in the traffic leaving the city for the bank holiday weekend around the Day of the Dead, in which Mexicans remember the deceased by decorating their graves and dressing in ghoulish outfits. Appropriate, given how many extra graves are dug each year for victims of pollution. It took us one hour to cover a mile of Insurgentes. You don’t need scientific instruments to tell you how bad the air is. Not only can you see it from above but you can taste it, and feel it in your raw throat and aching head after just an hour. It’s tangible.

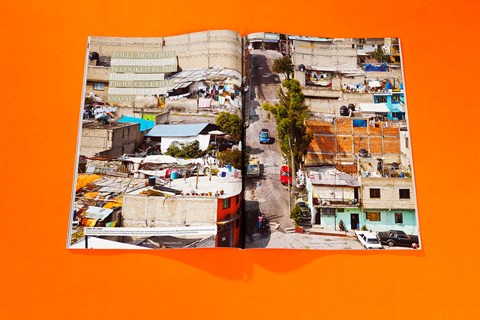

The final 15 miles of the trip are the most extraordinary. You think the city is contained in its bowl; you expect it to finish where the hills rise steeply on the northern side. But as the freeway climbs into them the city continues, like a grey concrete tide lapping up slopes so steep you’d struggle to stand up on them. This is the ‘barrio’, the vast shantytown that fringes the city, home to the thousands of people who move here every week and build a breeze-block home. It has grown so fast that the freeway that leads out to the 2000-year-old pyramids at Teotihuacan runs through it for 15 miles without an official exit. To get into the barrio we have to stop on the hard shoulder and drive down a footpath.

This might sound patronising, but the poorest parts of a town are often the friendliest. Despite the barrio’s reputation for crime, the Smart attracted only serious enthusiasm and good humour. At the base of the hill the older buildings are painted, often with Mexico’s hallmark vibrant murals, and the roads are largely paved. As we climb, the houses turn grey and the roads become remnants of flinty tracks and random strips of concrete. There are no streets; you just pick your way between the houses until the tracks get too steep to drive up. The Smart is defeated twice. Eventually there are just stairs cut into the hillside, steeper and longer than those that run up the pyramids, and the residents must carry everything up them, from the concrete to build their houses, to their shopping, to themselves at the end of a long day’s work.

We’ve reached the end of the city, but not the end of the story. What these people would like more than most things is a car. We can’t deny them one. We can’t tell them that we in the first world have had a century of fun with the internal combustion engine, but regrettably have buggered the environment for everyone else, so they have to keep walking. The car makers certainly won’t deny them, with radically cheaper new cars on the way. But one visit to Mexico City will show even the most ardent autophile that we’ve got to offer them something better.