► The latest from the Morgan Motor Company

► We get behind the wheel of the lairy ARP4

► Electric power for the upcoming EV3

The car maker that time forgot is changing, embracing aluminium, BMW engines and now hybrid power for its latest three-wheeled showstopper. Time to re-visit Morgan’s Malvern workshops.

It’s tempting to think of Morgan as the car world’s version of South America’s Yanomami tribe. They’re the people who wander around in loin cloths and pudding bowl hair cuts, aware of the outside world, but who choose to ignore it and continue instead with a way of life the rest of us left behind when wattle and daub rendered cave-living passé.

By rights Morgan should have died out years ago along with every other creaky name your granddad had scribbled on his schoolbag. Except that all the jokes about the archaic workshop and tooling so old no one actually knows whether it was first used before or after the war, the cars built from wood (only the frame, never the chassis, people), and suspension designs that went out with the ark are, truth be told, slightly disingenuous.

Throwback cars (and we say ‘cars’ in a sense looser than the marbles of the people buying them), like the phenomenally successful three-wheeler introduced in 2011, have dragged attention away from the efforts Morgan has made to pull itself in the other direction.

Morgan is a company of two eras. While the look of its cars, the craftsmanship and the English quirkiness comes largely from the classic range of Morgans it has been building since before our scuffle with the Hun, for almost 20 years there’s been another type of Morgan. A Morgan built around a state-of-the-art aluminium chassis, powered by a sophisticated BMW engine and paddleshift automatic transmission. A Morgan that now features traction control, anti-lock brakes and modern double-wishbone suspension.

And now the company is about to throw itself into the world of EV and hybrid power, unveiling an electric three-wheeler, the EV3, at this year’s Geneva motor show, and winning a £6m grant from the British government to develop a future range of zero-emissions cars.

We’ll come to that later. First, let’s get reacquainted with some slightly more traditional product in the shape of the new AR Plus 4. Although Land Rover happily blew the Defender’s long-service trumpet for its 67-year production run, Morgan’s 4/4 has actually been around longer. The more powerful Plus 4 arrived in 1951; both are still available.

Morgan revealed an 80th anniversary 4/4 on this year’s Geneva stand, but it’s the 65th anniversary Plus 4, shown last year, though not tried by anyone outside the factory until now, that’s the one worth bothering with. For the benefit of those of you not wearing a vest, the 4/4 is the quintessential Morgan. Four wheels, sweeping wings, modest four-cylinder power. Rides like its got 50p pieces for wheels. If the ARP4 is the 4/4’s daddy, it’s like the lion that eats its cubs for breakfast.

Developed by Morgan’s racing partner, AR Motorsport, the ARP4 features a Cosworth-tuned naturally-aspirated 2.0-litre four that makes 225bhp and a noise like a fairy-tale giant slurping the last dregs of a Diet Coke through a 40ft straw. In modern parlance, 225bhp isn’t a lot of poke, but these Morgans are light. Less than 1000kg light. In old tuned-car fashion, this one doesn’t want to know below 2500prm. Throw another 1500rpm at it and things get interesting, and by 6500rpm the needle is hurling itself towards the redline. Which you can’t actually see because it’s hidden behind the steering wheel rim. There’s a shift light but sadly that’s hidden too.

It sounds so epic it doesn’t really matter that the true level of performance is only sports- rather than super-car quick. And anyway, you’re busy enough as it is to be worrying about wanting more performance. To be frank, if the ARP4 is your first taste of classic Morgan, or of anything built before the ’70s, you’d swear it was broken.

Although the rear suspension has been upgraded to a five-link coil spring setup – a mod likely to filter down to lesser classic Morgans – it’s still a live axle duetting with a sliding pillar arrangement at the front. The thing bucks around like a Red Bull-fuelled rodeo steer on bumpy roads and the unassisted steering, heavy at parking speeds, and weighty everywhere else except when it goes disconcertingly light for no reason on the middle of a bend, is busy too.

The pedal heights make heel and toeing difficult, and when the mistakenly unlatched door flies open, it’s only the flash of white lines in my peripheral vision, and not the noise – which I can’t hear over the rest of the din – that alerts me. Fifty-five grand? Hmmm.

I love driving Caterhams, but the last classic Morgan I drove, a V6 Roadster in 2004, which I expected to push similar buttons, also left me non-plussed. Maybe it was rubbish, or maybe I just needed a little more time, because slowly I start to get the hang of the ARP4. You grow accustomed to the pedal positions, mentally prepared yourself for the steering weight to disappear alarmingly mid-turn and trust that it’s a transitionary sensation and you’re not about to understeer off the road. That’s just how it feels.

And when you start to trust a car, that’s also when you really start to enjoy it. Not just in a straight line, getting giddy to the sound of the Cosworth motor’s four individual throttle bodies, but in the corners too. The 225-section Yoko ADO8Rs actually produce plenty of grip, and there are proper four-pot calipers to dampen the drama before you dampen your pants. Objectively it’s no match for a modern car (ie, anything built since Suez) in terms of composure or outright dynamic performance. But accept that the primary goal of an entertaining driver’s car is to entertain, and not simply to get from A to B intact and in short order, and the ARP4 is absolutely valid.

It helps that it looks magnificent, bridging the gap between old and new but doing it from a completely different starting point than the Plus 8, which features the Aero’s aluminium architecture clothed in Plus 4-type bodywork. Morgan’s designer, Jonathan Wells, isn’t the biggest fan of the strikingly modern LED headlights, chosen by AR Motorsport to stress the link with the competition cars.

But the blackout chrome trim, the pearl paint and modern 14-spoke wheels… somehow it all works. There’s the same blend of old and new inside, where handsome and hardy box-weave carpet meets vintage-style toggle switches, beautifully shaped aluminium door cards and a contemporary alcantara-covered three-spoke wheel. Conspicuously absent is tree. It’s there – the whole dash panel is made of ash – but cloaked in black for a definite modern feel.

Back at the ramshackle collection of sheds that have constituted Morgan’s home since 1920, I see managing director Steve Morris choosing his Geneva motor show togs from a young Brylcreemed tailor dressed in plaid like Richard Prior in Superman 3. Morris, a former shop-floor worker, is the perfect embodiment of the boy-done-good fairy tale, and also Morgan’s desire to keep things in the family. But like all families, this one has its squabbles.

Since I was last here in 2011 to drive the then-new 3 Wheeler, Charles Morgan, boss and grandson of the company’s founder HFS Morgan, has been ousted, and Morris installed at the top table. Although Charles was instrumental in dragging Morgan into the modern age, pioneering the aluminium-chassis aero cars and the return of the 3 Wheeler, the relationship ended acrimoniously with accusations of misconduct.

Charles’s absence is the only sign of disunity here. From the offices located in the uppermost building, the oldest part of the factory and originally the location for three-wheel production after the Great War (how incredible does that sound?), we move through the works. If the standard of workmanship here – and the incidence of sons following fathers through the doors to the tools – is anything to go by, this is a happy workforce. And it is very much a workforce. While other car makers grapple with the philosophical, technical and legal issues surrounding autonomous driving, Morgan hasn’t doesn’t have so much as a robot.

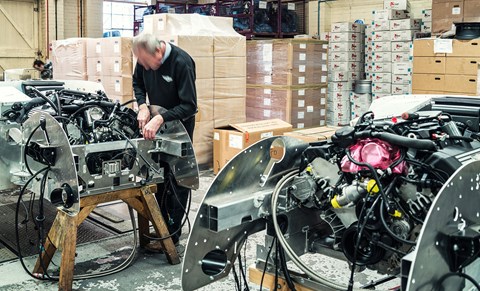

We see a swathe of the other 49 ARP4s – all sold, and denoted by their red, not black, steel chassis – making their way down the hill. For years, Morgans started life at the bottom of the hill and worked their way up, emerging near Pickersleigh Road until some bright spark realised it might make sense to do things the other way around and gravity do the graft. Only the 3 Wheeler gets a dedicated production line, although it’s actually more of a corner of a shed. The Classic and Aero cars are built together, first in the chassis shop, followed by the assembly shop, and later moving down into the woodwork department.

There’s no moving production line; the built-up chassis having their brakes and drivelines installed aren’t even on moveable dollies, but simple trestles. In the corner sparks fly as someone cuts off excess thread from the U-bolts holding a 4/4’s leaf springs to a live axle with an angle grinder under the gaze of a simple strip light. Your ears hear no music but your head is playing Dinah Shore 78s complete with scratchy vinyl sound effects.

In the wood shop, men with a sculptor’s eye shape the traditional ash frames that are criminally hidden below bodywork on the finished cars. Ash is the tree of choice, used for its lightness and ability to absorb sound, its tendency to grow straight and without many knots. ‘It used to come from Belgium,’ says John Burbidge, head of the chassis shop, ‘but now we get it from the UK. There was too much shrapnel in the trees from the war and it used to bugger up the machines.’

Ash is also used for the dash panel but probably not the motor show stand that lies in front of me in sections. Was there another company at Geneva whose designer and engineers had inked out and manually constructed the shape of both the cars and the plinth they sat on? Of course not.

‘There’s 207 years of Morgan experience in this shop,’ says Burbidge proudly. Finding young people with the skills required to build these cars isn’t easy. You don’t roll out of a BTEC college course knowing how to build a car designed when watching a film at the cinema without a man in front playing the piano was still a novelty. Yet there are plenty of young faces here, and everyone can learn something new regardless of their age.

‘The dashboards were actually done by outside suppliers until recently,’ Burbidge admits, picking up a beautifully finished slab of walnut-coated ash. ‘But I felt we should be doing it ourselves. The lads started with one model and now we do them all.’

Paintwork is also done in-house, as is the trimming, in the final assembly area. The older-style classic Morgans stay close to the original recipe, but even they haven’t been immune to the march of technology. Modern adhesives have slashed the time needed to bond the plies that make up the curved wooden frame over the rear wheelarches. Previously they needed six hours clamped in a medieval-looking jig that’s at least 64-years-old but could be 80. Now the job’s done in two.

Similarly, wings once fashioned from steel are aluminium these days. They’re produced offsite by a company that makes panels for big money British supercars, but the finishing is all Morgan’s. We watch a pair of workers with the hand/eye coordination of a watchmaker stamping the louvres into one bonnet.Across the hall, another nonchalantly chops a 40cm-long strip from the bottom of another bonnet with some tin snips having measured only with his eyes. It fits perfectly. Then, in the corner of one room I spot a 3D printer, a godsend to low-volume car companies like Morgan. Now it can prototype new parts in a fraction of the time (and cost).

Stripped bare before us, the huge technical differences between the aluminium-chassis BMW-powered cars and the older classics is far more apparent than it ever is on the showroom floor. I can’t help but wonder about the older style cars.

I can understand how the baby boomer generation might have lusted after one, fulfilling that dream held since a creaky 4/4 trundled past their school gates during a game of conkers. But those blokes are in their 60s and 70s now. Isn’t the supply running dry? Do younger sports car fans, or even middle-aged ones, lust after a relatively slow, dynamically compromised (if admittedly beautifully finished) yesteryear ragtop?

That the traditional cars account for over one half of the circa-850 annual output suggests demand for the classics is still strong, at least for now. Three quarters of Morgan output goes overseas, and a huge number of those to Germany and France where Anglophiles wear flat caps and celebrate the kind of imagined Englishness of Midsomer Murders. The vastly more complex, more expensive BMW-powered cars (prices start at £81,140 versus £34,925 for a basic 4/4) shift between 100-150 units a year, and the fascinating V-twin 3 Wheeler, a car that celebrates Morgan’s heritage yet manages to do so with complete cross-generational appeal, finds around 250 homes annually.

When we reach the 3 Wheeler production area there are 11 cars in various stages of undress, from bare chassis to the fully-built pinstriped Geneva expo car, but no sign of the EV3 electric variant that made its debut at Geneva. What started as an interesting idea, to resuscitate the long since forgotten car that made Morgan’s name, has snowballed into something massive. The plan had been to build 300. The five-strong assembly and road-test team is currently at 1500 examples and counting.

Being classed as a motorbike rather than a car helped here, reopening a door to the North American market that closed to Morgan when a safety exemption expired in the early noughties. And by the year’s end those same dealers could potentially have a whole raft of new product to sell. A US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration bill introduced at the back end of 2015 now allows companies to produce up to 15 examples of a car that wouldn’t meet mainstream safety requirements provided it is based on a design older than 25 years and is powered by an engine that meets current emissions legislation. The Aero 8 still won’t be granted a visa, but the Plus 8 (an aluminium Aero chassis clothed in classic-style bodywork) might just squeak through, and the steel chassis cars are sure to find a cult following.

That cult following was always the reason Morgan was able to get away with ludicrous waiting lists of up to 10 years, but like the styling, they’re a thing of the past. ‘Sometimes we used to ring deposit holders up to tell them their build slot was approaching and it was time to talk about a more detailed specification, and it transpired they’d actually died,’ admits press and marketing man, James Gilbert. ‘These days we’ve got the waiting list down to around six months.’

And what’s six months between friends? For Morgan, a company continually blurring the distinction between the old and the new, the concept of time is as fixed and as fluid as it pleases.

The specs: Morgan ARP4

Price: £54,995

Engine: 1999cc 16v 4-cyl, 225bhp @ 6500rpm

Transmission: Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Suspension: Sliding pillar front; five-link live axle with coil springs rear

Performance: 5.5sec 0-60mph, 130mph (all est)

Length/width/height: 4010/1720/1220mm

Weight/made from: 927kg/steel, aluminium

On sale: all 50 sold

Rating: ****

EV3: Morgan goes electric

If you asked most people to rank the world’s car makers in order of likelihood to rush to embrace clean power, Morgan would be subterranean. But the team at Malvern has been investigating green technologies for over 10 years, stretching back to 2005’s LifeCar project, and actually produced a Plus 8-based EV concept in 2012.

That stuff though, was just playing. This year, things get serious, starting with the EV3, a production-ready pure electric version of the much-loved 3 Wheeler revealed at this year’s Geneva Motor Show. The real action, the fruit of a business plan that has netted Morgan and technology partner Potenza a £6m government grant to develop electric and hybrid vehicles, won’t start until 2019. If that same plan works, Morgan will double its output to almost 2000 units a year in the next 10 years.

Instead of the standard 3 Wheeler’s American-built S&S V-twin petrol engine, the EV3 features a 62bhp liquid-cooled electric motor powered by a 20kWh lithium-ion battery housed within the tubular chassis. And rather than Morgan’s traditional aluminium bodywork, this one wears sophisticated carbon panels, a company first.

Although it weighs around 25kg less than the 525kg petrol model, the EV3 is slightly slower, Morgan quoting a sub-9sec 0-60mph time, more than a second adrift of the V-twin machine. Top speed is down from 115mph to 90mph too, though anyone who’s actually been brutally assaulted by Mother Nature at the wheel of a 3 Wheeler is unlikely to complain. The range is 150 miles but you’ll likely be begging for it to expire at half that.

Given how fundamental the exposed V-twin engine was to the styling of the original car, Morgan’s design head, Jonathan Wells has done a spectacular job here. Last year’s EV3 prototype simply had a boring orange box in the nose, but the production car’s offset headlight and brass cooling fins give the EV a character all its own – and more than a hint of Jules Verne. Whether the car’s dynamic character can withstand the loss of the V-twin’s noise and vibes is a crucial question we can’t yet answer. EV3 deliveries start later this year, while prices start at north of £30,000.

The designer: Morgan’s Jonathan Wells on ‘1950s robots and Back to the Future’

‘For me Morgan is about the people, the craftsmen, the atmosphere,’ says chief designer Jonathan Wells. ‘You can build almost any shape, but as soon as you know it’s put together by these craftsmen, it could still be a Morgan. Even applying composite technologies; I don’t believe that ruins the charm of coach-building.’

If that sounds like the prelude to some radical reinvention of the Malvern company’s design and engineering language, it is. And it isn’t.

‘I think we can be flexible with the design,’ says Wells. ‘There’s a lot of room for stretch. We’ve created some radical looking cars like the Eva GT, which looks nothing like a 4/4 but people still relate to it as a Morgan. The challenge is communicating to the customer that the car still retains its integrity.’

But here comes the pacifier for the apoplectic flat-cap brigade: ‘Having said that, I don’t think an ultra modern design is the way to go.’ Wells can’t give too much away about future product, but we talk about some of the most beautiful machines of the 1930s – Delahayes, Talbot Lagos and the Count Trossi SSK – cars that are clearly of their time, yet manage to appear shockingly modern at the same. He then suggests the new EV3 as a car that uses historical cues yet appears surprisingly contemporary.

‘Believe it or not I took my inspiration from a Napier Railton,’ says Wells, then laughs, adding: ‘and 1950s robots and the steam train from Back to the Future! It’s a lot of fun seeing how far you can push the designs.’

Are there design cues that are fundamental to any Morgan? ‘The face of a Morgan is important, the round lamps and smiling grille. And the wood,’ Wells responds. What about the separate wings? ‘Lower down my list than some people would have them.’

When Wells joined Morgan as a graduate he introduced modern 3D modelling technologies to a design department still working in the past. Now, having replaced Matt Humphries as head of design, he’s charged with introducing a new customer demographic.

‘We have many customers who are very important to us, but perhaps some of those haven’t bought a new car from us for 30 years. We need to be realistic about the future of the classic range. We need to also be looking at new markets.’

And a new lightweight platform to go with the new electric and hybrid drivetrains. ‘Designing a new chassis that can take multiple drivetrains, electric power and different styles of bodywork is a fascinating challenge,’ he says. Given that Morgan’s £6m government grant is some £3,144,000,000 less than Ford has pledged to spend developing its own electric cars over the next five years, he’s not kidding.