► The greatest slow cars of the 1980s

► Reappraising the lowliest motors

► A CAR+ archive treat from 1985

Cars come no cheaper than these; they amount to the cost of one lower-strata BMW. They are models about which people make derisive remarks, usually because they are just practical, basic transport. Most of all, one can’t seem to forgive them for not having crippling price tags. But here, we’ve tried to look at the ‘poverty models’ in a different light…

There came a day when the laughing had to stop. Though most people who though about it seemed happy enough with out GBU-view of the cheap, styleless cars at the very bottom of the British market – Lada, Skoda, Yugo, Reliant Rialto and the rest – several things happened which made us suspect that we were all being carried along on the momentum of jokes.

First, every one of the bottom-line marques received a series of refinements aiming at making them more acceptable. Second, it becomes clear that resale values of Skodas and Ladas were showing marked improvement. Third and most compelling of all, the bottom line cars seemed to be enjoying their own private sales boom; styles cars seemed actually to be getting fashionable.

The progress, quietly made, has been striking. Since 1981, sales of FSO, Lada, Yugo and Skoda cars, taken in total, have leapt ahead by 44percent – in a market where competition has become ever stronger and where, through discounting, ‘good’ cars have become markedly better value. By ways of comparison, sales of the Ford Escort have risen by 21percent since 1981.

And if you think the 40,000-odd Yugos, Ladas, Skodas and FSOs that made it onto British roads in the past year are still pretty small potatoes, it’s worth remembering that this is nearly six times the combined ’84 UK sales of Alfa Romeo and Lancia cars.

We decided, early on, that a trip to the test track to ‘evaluate’ a cross section of Britain’s poverty models was likely to be unproductive; by normal family saloon standards the cars would not be very fast and would contain outmoded engineering. That much we knew already. Instead, we decided to put them to the same more practical test that we frequently put far more powerful and expensive cars through; to cruise them hard on a long trip, mixing back-roads and motorways, driving for economy and going flat-out as well. We wanted to form opinions about their convenience and character, using them as owners would.

Choosing the cars proved difficult. A complete list of poverty models takes in the Citroen 2CV, Daihatsu Domino, Fiat 126, FSO 1300,1500 and Polonez, Hyundai Pony, Lada Riva, Reliant Rialto, Skoda Estelle Two, Suzuki Alto, and Yugo 311 and derivatives. It was too many for our test.

We eliminated the Fiat 126 for being unrelievedly arthritic and incompetent, the Diahatsu Domino because at £3300 it is just a little expensive for the class in Lada terms and the Hyundai Pony and Suzuki for the same reasons.

The Skoda and Reliant chose themselves because they are so universally condemned by reports in organs as disparate as Motoring Which? and Country life. Such unanimity among scribblers is suspect. Motoring writers criticise the Skodas and Reliants because it is safe to do so – they use the cars to maintain credibility – by showing that they can criticise something.

As to the others, we decided to include a Lada Riva (the comprehensively equipped 1500GLS at £3475) because it represents the top-selling bargain-basement marque in Britain and it also stands, to a degree, for the other ex-Fiat designs, FSO Cars and Yugo/Zastava.

Citroen Deux Chevaux Special we included because it is a car of minimal capability and build quality, praised by us and others mainly on the elusive basis of its character. Including it in the Slow Family of four, we felt, would try our previous conclusions about it and thoroughly test the others.

We hacked the cars about in Greater London, in the growing winter gloom and mainly on damp, crowded roads for most of a week. Then we took them on a journey we estimated would cause problems for each – a straightforward thrash down the M4 motorway, all the way to Swansea in South Wales, before we turned them north and headed up through Pontardawe and Brynammon on narrow, twisting and hilly roads scattered with miners’ villages, to Black Mountain, scene of our photographic set for Fast Family at the beginning of the year. That was the story which gathered the Ferrari Boxer, Lamborghini Countach, Aston Martin Vantage and Porsche 911 Turbo into one feature. The motorway, hill roads trip plus our hail to overnight accommodation in a very special country house hotel on the River Usk at Crickhowell, not far from Brecon, put another 600miles under the wheels of our ‘slow’ cars.

After this, and some performance testing, and a lot of discussion, we knew a great deal of the cars – and about the family to which they belong. We found, as the GBU reflects this month, that some of our conclusions needed to change.

To make the whole thing more meaningful, we drew up a scale we called the Cavalier Rating, for which the cars were allotted points on a scale of zero to 10 in the categories of Performance, Economy, Handling/Stability, Comfort, Finish and Durability. A car which reached the standard of a Vauxhall Cavalier 1.6GL scored 10 points, one which merely attained the standard of the 126 was awarded none. The aim is not to compare the four cars directly – they vary in price, function and format – but to establish a level of competence for the whole Poverty Model breed. These were our findings …

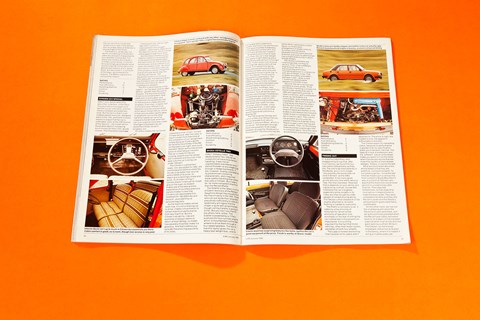

Lada Riva 1500GLS

The Lada reminds you both of how far car design has come since the mid-‘60s since the Fiat 12, on which this car is based, was around, and how enduringly pleasant those cars were. The car feels tall and quite massive alongside a modern design, and you’re aware of the space-consuming nature of its front engine/rear drive layout. The vertical seating positions and the surprisingly opulent GLS seats (does this car really cost £350 less than a Metro City?) allow plenty of room in front, but knew room is restricted in the rear. No problem with headroom in such a small car, though.

The Lada we tested has a 1.5litre, single overhead camshaft engine familiar to Fiat adherents in the ‘60s. It has a longer stroke than bore (and is flexible as a result) but its top end push is restricted as you’d expect of a 77bhp engine in a car that weighs the best part of 2400ib when ready for the road. Still, it’ll turn 95mph on the flat, given time, and will cruise all day at a true 80mpg without undue distress. From a standing start it will sprint to 60mph in a shade under 15sec, which is quite quick enough for the market. Fuel economy usually works out around 27-30mpg mark, which is not especially good for a car of this capacity, carrying ability and performance. But it’s acceptable, like the car.

You can enjoy driving the Lada Riva once you remember to keep the tacho needle (standard in a GLS) below about 5200rpm, give the four-speed gearbox’s weak synchromesh time to work.

The steering is woolly at the straight-ahead and low geared, but its fairly light. The car is an inveterate understeer but it corners tidily enough and has no bad habits in the wet. The brakes – front disc and rear drum, power assisted – feel wooden but they are powerful when needs be, though the presence of a rear pressure limiter isn’t reflected in the car’s tendency to lock its rear wheels in hard stops.

The Lada’s finish isn’t very good. It’s solidly constructed but the materials – principally facia plastics and other trim bits – are of low grade and the paint and welding is quite poor. Like Fiats of the ‘60s, the car still seems to have rather a lot of moisture traps which could threaten the body’s longevity. The Lada had no style at all (we agreed the awful block – shaped front grille removed all chance of that) but it seemed unfailingly sensible.

Rating

Performance 6

Fuel efficiency 7

Handling/stability 6

Comfort 6

Finish 3

Durability 5

Reliant Rialto 2

The Reliant Rialto 2 is, according to the law, not a car at all. It is built with three wheels, to weigh less than eight hundred – weight at the kerb, so as to qualify as a motorcycle combination. That allows it to be driven by motorcycle licence holders, and to qualify for motorcycle tax rates.

The Rialto, subject of all those Plastic Pig jokes, is an all glassfibre body mounted on the simplest of ladder frame chassis, made of galvanised rectangular-section tube. The rear suspension comprises cart springs suspending a live rear axle; the front wheel is mounted on a leading link, controlled by a single spring/damper unit. The engine, an all-alloy four-cylinder unit with cast iron liners, is made only for the Rialto derivatives. It is a pushrod overhead valve design whose extreme light weight allows the machine’s acceleration (with two occupants) to shadow that of a Lada Riva. It’ll get to 60mph from standstill in about 17.5sec. The 75mph top speed claimed by Reliant is actually at least 5.0mph less than the machine will run quite easily (and ours was still quite tight in the engine) but the problem fro that machine is that I’s none too stable when the speeds reach the 80s. The Rialto has spectacular fuel economy; it almost always beats 50mpg when driven sympathetically.

The Rialto has a surprisingly interesting cabin layout, though the rudimentary design of its tiny, shapeless front bucket seats promise little comfort. Still, there’s a reasonable facia, a well-designed three-spoke steering wheel and a large centre console with a short-throw gearlever sprouting from it, to make you think for a second that the machine is quite sporty.

The console turns out to be a shroud for the engine, which for stability purposes is mounted far back in the chassis. That means it’s noisy in the cabin when the engine is worked; Reliant say adding the noise suppression material they’d like would increase the weight too much. Thus you hear a lot of the engine’s tappet noise and that can be annoying. On the other other hand, the car’s lightness and the engine’s comparatively long stroke mean it is very flexible. And because the gearchange is quick and precise, and the steering light, you can see why the Rialto has its adherents.

But for those who drive to cover distance quickly, the car is dreadfully unstable, both on corners taken fast and in quite gentle crosswinds. If the wind gets at all fierce the safest thing to do is to stop, so dangerous is the car’s instability. The only way to drive it is to exercise extreme caution in all corners, especially left handers, taken one-up. Then, the car can lift its inside rear wheel a foot clear of the tarmac, spin its power away and deliver a severe fright to the driver.

The Rialto is, as we say, not worth considering for those who have any prospect of passing the four-wheeler license test. For those few citizens who haven’t it makes more sense, if only for its surprisingly good resale value and its long-life combination of a galvanised chassis and a ‘glass body. But we couldn’t, in a month of Sundays, recommend it to anyone. The Metro-size price is just another reason.

Rating

Performance 4

Fuel efficiency 10

Handling/stability -5

Comfort 3

Finish 5

Durability 7

Citroen 2CV Special

What has been written about the ‘cuteness’ of the Deux Chevaux has encouraged us to see the car as individual, and not merely out-dated and extremely slow. But the fact is that it is an underpowered machine, designed early in the ‘30s, and there is every reason to argue that the car is outmoded, even at the £2674 price of the Special – the model which those dedicated to not paying much money for their cars, would choose. The Charleston package – trendy paint job, interior light, rear shelf, some trim improvements and a bigger speedo – adds nearly 20percent to the Special’s price, which is sheer extravagance (see Giant Test).

But the Duex Chevaux scores heavily indeed for its versatility. It has easily removable seats, the roof comes off, the bootlid can be removed, and as a result it can carry remarkable loads. As a four-door saloon it still does a fair job of hosing four adults, though the lack of shoulder width requires that they be friends. The equipment and trim is no more than adequate; the Special merely has the basics any car needs to function and that is all. Décor is simply non-existent.

The 2CV’s performance on the road is – as has been said so often before – greater than the sum of its parts. The machine must be driven to its fullest extent, near-peak revs in every gear, and cruised with the accelerator flat-to-the-boards to make sensible progress. Even then, it needs half a minute to reach 60mph from standstill and can only be relied on for about 72mph flat out. Some of that velocity ebbs rapidly away on gradients, but on the other hand the needle will wind far onward to the 80 mark when the car is on a gentle motorway slope. Intelligent slipstreaming can assist the Citroen driver’s progress, too.

All of this makes the car sound unbearably slow. In fact, our test Cit was second, after the Lada, to reach London from Swansea at the completion of our assignment, simply because it had a gentle tail wind for the entirety of the M4 on that particular night, and could maintain 75mph without excessive boom or other fatigue inducers. The car is made for flat-out cruising; experts say the valves don’t commence to bounce in top gear until the car’s doing just under 100mph.

The Citroen’s rudimentary seats, non-adjustable for rake are comfortable for 200mile stretches, its ride is far better than any car within £2000 of its price, its steering is surprisingly sharp and quick, its drunken rolling in corners doesn’t interrupt its limpet grip on the road, its modern brakes are of the best and the experience of countless previous owners makes it clear that Citroens can stand pretty firm treatment for 100,000miles and beyond – provided they’re serviced regularly.

So the machine makes sense, even now. It is not a relaxing car to drive; it takes concentration to extract maximum performance from any machine. But the Citroen’s reliability, ride and economy (it always seems to return at least 42mpg, no matter how severely thrashed) make it a good buy. And that’s before you consider the enduring popularity of its looks.

Rating

Performance 2

Fuel efficiency 9

Handling/stability 8

Comfort 7

Finish 0

Durability 9

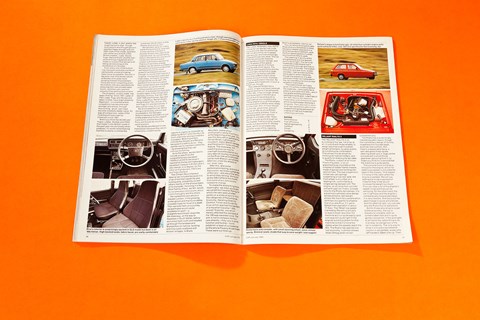

Skoda Estelle Two

First things first: The Skoda Estelle Two 120LSE we tested did not have treacherous handling. It was not an unpredictable oversteerer and it did not threaten at any stage to go through a hedge backwards. It did, however, display oversteer as its predominant cornering characteristic, and it required more careful handling that either the Lada or Citroen. But it was a far, far more competent machine than the Reliant Rialto.

The Estelle is the latest in a line of Czech revisions of the Renault Dauphine design they bought from the French early in the ‘60s. Those who can put aside their long-held prejudices sufficiently to look at it objectively will agree that the shape is quite well proportioned, though calling it pretty is going a bit far. But you can’t say that for the others here, either. The Estelle is powered by a 1174cc pushrod ohv four-cylinder engine which is mounted behind the rear wheels to drive them through a dour-speed gearbox. The fact is that this layout gives the car a heavy rear weight bias, and its swing axle rear suspension systems (the front is by wishbones/coils) give it sudden breakaway characteristics on the limit, of a kind many drivers don’t expect.

What we found is that at sane velocities, the car’s rear weight bias gives it light steering and a delightfully precise turn-in for tight bends. It also gives it an unusual pitching ride, particularly at low speed. It is saved from being really disconcerting by the fact that the car feels very solid and suspension noise is quite low. In fact, the Skoda’s finish and its equipment is exemplary. The 120LSE model we tested (at £3299) was very nicely screwed together and came equipped with fat steel belted radial tyres on alloy wheels, mudflaps, twin exterior mirrors, a vinyl roof (if you like them), four-jet windscreen washers and halogen headlamps. Inside there was a stereo of cloth-faced fully reclining front bucket, fold-down rear seats for load-carrying, a tachometer, a rear window demister, a laminated windscreen and a tool kit that would have done justice to a Boeing 747.

The 120-engined Skodas will run to a little over 90mph flat out, and accelerate from zero to 60mph in around 20sec, which is not quick. Yet strangely enough, there are parallels to be drawn driving the Skoda and a Porsche 911! The Porsche has the same rather rudimentary control layout, a complicated arrangement of heater controls, its noises and vibrations emanate from the same peculiar direction and even its gearchange has a slight relationship in effort, though distant.

The Skoda’s problems are surprisingly few, but they’re serious. First, it has a 4000rpm engine boom which is disconcerting and finally infuriating because it corresponds with about 70mph in top. That problem should be alleviated – perhaps curved – when a new 1.3litre five-speed Estelle appears in a month or two.

Second, the car is annoyingly unstable in crosswinds. Third, the Skoda’s handling is simply not the fail-safe variety that cars in 1985 are expected to provide in ideal conditions, with a competent driver up, the Estelle is a controllable, even entertaining oversteerer. We found it more fun in the twisty bits than the others. But the fact is that an unskilled driver, who misjudges a wet, downhill bend and stamps on the brakes is still likely to be in trouble. Under those circumstances, that tail is hard to catch. The cure for the problem would surely be blanket fitment to Estelles of the Rapid coupe’s semi-trailing arm rear system. Then, for the money, there would be surprisingly little to complain about. Only the name would remain a stumbling block.

Rating

Performance 4

Fuel efficiency 7

Handling/stability 3

Comfort 6

Finish 9

Durability 8

Finding Out

It is both cheering and disappointing to say that, after much testing, we found the four cars stand substantially as they did. The one to be hard done by is the Skoda, which is no longer ‘very possibly the worst new car sold in Britain’ as the GBU contended. It has many good points and only one really serious flaw, the final oversteer. How bad that is depends on your ability and vigilance as a driver, but we feel it remains the car’s bugbear, especially since models in its class are often bought by older people of limited driving ability. The Skoda’s other drawback is the stigma attached to its name. Nothing is harder to overcome.

The Rialto is not really a car. It caters to a tiny minority of motorists for whom either economy of operation (not purchase) or the fear of sitting the car license test is the paramount importance. It is a rolling argument for the fact that motor vehicles, other than motor cycles, are better off with four wheels.

The Lada is honest and boring. It will soldier on for years and it deserves to. The price is right; the market is sure, the appeal to enthusiasts is minimal.

The Citroen earns its interesting status, because its performance is greater than its specification leads you to believe it will be. The Special’s lack of pretension and the ‘different’ nature of the beast make you warm to it all the more when it produces results that are more than worthy of mainstream designs. Simply, it stands the test.

What we discovered about the whole breed is that they are practical, civilised transport. To our great surprise – since the last time we made such a convoy trip from London to Black Mountain it was in a clutch of 160mph cars – was that the machines could cover ground in a surprisingly able manner. They required, furthermore, no fuel stops that involved us in expenditures to make the eyes water, they were completely reliable and they (the Reliant’s seats and the Skoda’s exhaust boom apart) were fairly comfortable.

On the other hand, we had not the slightest qualm when the Skoda and Lada went back, and were positively pleased when the Reliant was safely delivered back to its makers (it having been a period when high winds and rain were lashing southern Britain). The Citroen, remained at its post in the family, where it is hoped it will put in a few years yet.