► In search for Arabia’s lost city of Ubar

► Gavin Green in a Range Rover TDV8

► Retracing the steps of Sir Ranulph Fiennes

No, not Indiana Jones but CAR‘s own Gavin Green retracing Sir Ranulph Fiennes’ Arabian tyre-tracks in the sensational Range Rover TDV8

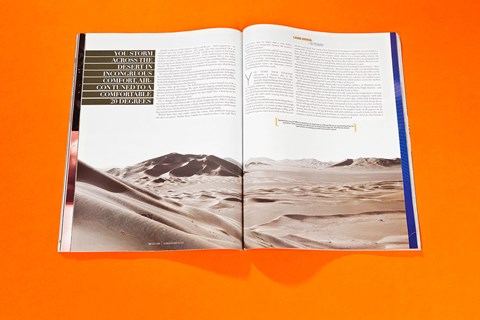

Standing on top of a mountain of sand, all around is Arabia’s Empty Quarter, or Rub al Khali. The dunes stretch as far as you can see, golden orange in the clear afternoon light. It is the world’s largest sea of sand, bigger than France or Texas. It’s 44 degrees and a hot wind is blowing. Wisps of sand spray from the dunes and down on the ground, far below, the air is filled with fine dust. My hair is full of sand grains, my sunglasses and clothes are dirty, and I need a drink.

Around 1700 years ago, caravans of camels – up to 2000 strong – would trek through this uninhabitable Arabian land, carrying their valuable cargo of frankincense on its way to the northern markets of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Persia. The camels would be newly watered. The men too would have been in good spirits, for their last stop was famed for its wealth. That last stop was the fabled city of Ubar.

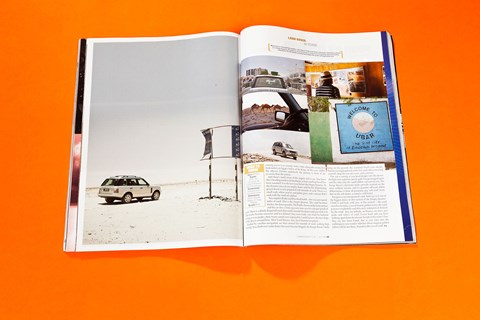

We are on the southern fringe of the Empty Quarter, near the Saudi Arabian and Yemeni borders, in Oman. Far below, our modern-day ship of the desert, a Range Rover TDV8, has been gingerly skirting around the dunes – in low range, ride height pumped up, ‘sand’ mode selected in the Terrain Response – seeking whatever shingle and scrubland it can find. The ground is firmer there, but we still get badly stuck in the soft sand. Time to use the sand ladders and dig troughs around the tyres.

We are retracing the footsteps of the world’s greatest living explorer, Sir Ranulph Fiennes, the latest in a long line of 20th century British adventurers who set out to find the lost city of Ubar, tagged by TE Lawrence – Lawrence of Arabia – as the ‘Atlantis of the Sands’.

Ubar, or so the legend goes, was a magical oasis supposedly of golden pillars and fabulous wealth, sited in the sands of the southern Arabian Desert. It was destroyed, says the Koran, by the wrath of God, to punish the decadent Ad people who lived there. It became important in about 2500BC, when camels were first used to carry goods across the desert, and was destroyed between 300 and 500AD. It thrived because it was one of the major trading posts for frankincense, the richest commodity of ancient times, worth more per measure than gold. The gum from the stumpy frankincense tree was highly prized for its scent, used for the finest perfume and incense. It was also widely used in religious ceremonies and in medicines. Celebrity customers included the Queen of Sheba, the King of Persia, Nero and (courtesy of the Three Wise Men) the baby Jesus.

Great caravans of camels, en route from the coast of Dhofar (in southern Oman today) would head through Ubar on their northerly land route. The mountains behind the Dhofari coast produced the world’s finest frankincense (Dhofari frankincense is still used in expensive perfumes). This desolate place was the richest civilisation in the ancient world.

Its major city now is Salalah, and it was to this dusty seaside town that Sir Ranulph came on his 24-year quest to find Ubar. Fiennes first came to Dhofar in 1968 while fighting for the British-supported Sultan of Oman against communist insurgents from neighbouring Yemen. Between counter-offensive operations, Fiennes heard about Ubar and, ‘from that moment on, a Walter Mitty-like desire grew in me into a self-imposed but undeniable quest: I would find the golden pillars of Ubar however deep they lay buried within the sea and sand and however long it might take,’ he wrote in his 1992 book, Atlantis of the Sands.

Initially using two of the Sultan’s army Land Rovers – ‘both clapped out’ – he ventured into the Empty Quarter. The guide who first mentioned Ubar to Fiennes suggested it was north-west of Fasad – which means ‘rotten’ or ‘bad smell’, owing to its sulphurous underground water – in the southern part of the Empty Quarter. So this is where Fiennes and seven men ventured. This is also where we’re going in our Range Rover. Just as we see no signs of golden pillars, nor did Fiennes. He returned to the desert on a number of occasions, before eventually succeeding in 1992, when he used Land Rover Discoverys as transport.

His successful trip was the best financed and the best organised, and enjoyed the best technology. NASA space satellites identified possible buried ruins, helicopters were used for reconnaissance, Juris Zarins – a specialist in Arabian archaeology – headed the digging team, various Omani companies provided sponsorship and the (new) Sultan of Oman gave his blessing.

Fiennes takes up the story: ‘The NASA discovery, in fact, turned out to be a different period of archaeology. We spent months digging around much of the Dhofar area based in Shis’r, a town on the road to the Empty Quarter from Salalah. We went to every known archaeological site that might have a bearing on the frankincense trade. All without luck.’

Shis’r, though, held promise. NASA images had shown old trails leading from the coast to Shis’r and then north to the Empty Quarter. Plus it stood on top of the best aquifer in the region, a likely stopover for the caravans. Near Shis’r were some ruins, dating back several centuries. It was when Fiennes and his team dug around and underneath these ruins that they finally got lucky.

‘Within three days, nine inches under the surface, Juris produced 3000-year- old chess set pieces. Within three months he started to trace a city wall. We’d found Ubar. But we didn’t find it with NASA technology, as is frequently claimed. We found it largely through luck.’

Fiennes later handed over 13,000 historical artefacts to Oman’s minister of heritage. According to archaeologist Zarins, the reason for Ubar’s sudden destruction was the underground water: the limestone caverns collapsed and so did Ubar’s walls.

We start our four-day adventure, as Fiennes did, in the Omani capital, Muscat. We collect our specially imported Range Rover TDV8, a model not sold in Oman (where diesel cars are virtually unknown – little wonder, when petrol costs 20p a litre) and then begin the 650-mile drive across the flat gravel and sand to Salalah on the south coast. Only the odd camel straying onto the road breaks the monotony.

The TDV8 is a wonderful mate for the Range Rover: powerful, smooth yet tolerably economical (25mpg is surely not bad for a 2.7-tonne, leather-lined 4×4). This British-built (in Dagenham) 271bhp, 472lb ft engine gave a new lease of life to the off-road legend. We storm across the desert in incongruous comfort, air-con tuned to a comfortable 20 degrees, lazy engine turning over at barely more than idle. This is not a sports utility vehicle; it is a luxury utility vehicle, the Rolls-Royce of off-roaders and, as we waft along, we’re thankful for the easy-going gait and supple springing. In London, the Range Rover feels like Gulliver in Lilliput. Here it seems rather on the small side: Oman is full of XXL American and Japanese 4x4s.

Next day, we head to the finest frankincense-related archaeological site in Oman – Khor Rori, known in ancient times as Sumhuram – the ancient port 30 miles east of Salalah where dhows laden with frankincense sailed to Africa, Asia and Europe. Then head north over the ragged Qara mountains, the 3000ft high backdrop to Salalah that gives the area such an extraordinary microclimate: while the rest of Oman bakes in summer, the southern coast enjoys the refreshing leftovers of the Indian monsoon from across the Arabian Sea. June to August is the coolest time of the year.

After crossing the Qara range, Oman takes on its familiar aridness. At Thamrait, on the old frankincense trail, we fill the car – there is no fuel available in the Empty Quarter – and turn off the tarmac road onto a graded dirt track that leads to Shis’r. It’s flat and heat shimmers in the distance. It’s only 10am but the temperature is already 42 degrees and rising. The sun stands smug over one of its greatest conquests. Little tufts of grass, acacias and tamarisks cling to life. You see some ugly, stubby little frankincense trees growing out of rocks. Fine dust plumes from the tail of the Range Rover, hang in the still air. The track is badly corrugated and there are a few washouts, where infrequent flash floods have eroded the road. The Range Rover’s air springs ride the rough well. There’s a rattle from the dash on rougher tracks (it disappears on the tarmac) but otherwise the big Brit feels solid and confident, as much at home in Arabian sands as it is in a peatbog in Perthshire or a mews in Mayfair. The cabin, once lauded as the finest interior of any road car, has dated a little and some of the switches now seem too small. But you sit in comfort in these high armchairs, sultans of the sand.

Shis’r is a small town on a hillock. There is a government complex, with Omani flag flying, and another modern complex of small concrete homes where bedouin are housed. Then our gaze is trained on a fenced-off site little bigger than a football field, opposite the concrete homes. This is the reason we have come to Oman: the lost city of Ubar. We’ve found it.

Today, it doesn’t look much. There are decayed stone pillars and broken walls and helpful signs, in English and Arabic. It is built around a limestone cliff, at the bottom of which is a spring, filled with sweet water. There is a small dusty museum and our guide goes into a nearby grocery store to get the key. Inside are some photos and a few trinkets. The valuable finds have been dispatched to museums far bigger than this.

The archaeologists have gone, after more than a decade of digging. Their work proved that Ubar – once surrounded by verdant countryside, not this dusty bowl – was a major settlement, spanning many millennia, and was certainly a key stopover and trading post on the frankincense route. Alas, there were no sign of golden columns. Nor was there any categorical proof that this was indeed the Ubar of rich and glorious legend. It may possibly be another lost city, or simply an important trading post. Yet its significance remains undiminished, even if coming across it so casually today ranks alongside seeing fast food outlets in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. In this case, unlike the odyssey Fiennes undertook, the journey is more of an occasion than the arrival.

And there’s much more of this region still to see. We leave Shis’r heading north to Al Hashman, as bad-smelling Fasad has been renamed. It is the last town before the Empty Quarter. In the distance I can see mighty dunes and the flat shimmering gravel desert is now peppered with mounds of sand. There is a small wadi, where acacias and palms grow, and a stream that’s rank with the smell of sulphur.

We stop for drinks and then head north – into 225,000 square miles of sand. This is the Empty Quarter. The sand becomes thicker, the dunes grander. The Pirellis thrum on the loose surface and the car does a little jig every time we hit a deeper patch of sand. There is a thinly disguised track that winds around the dunes and we stick to it. The tracks become narrower and less defined; they were made by bedouin acting as tour guides, their trusty camels now replaced by Land Cruisers, the new ships of the desert around here. Most Land Rovers, alas, have become too pricey.

Guided by satellite navigation, we skirt around the mounds of sand, seeking firm footing. We climb over some dunes but soon become bogged, the Range Rover’s belly lying on the ground, the tyres deeply buried, clawing hopelessly at the fine sand. After extracting ourselves, we let some air out of the tyres to aid traction, and then continue.

The sun is setting as we head deeper into the desert, the light now a glorious poetic gold. We get bogged again and this time only the sand ladders can extract us. The Range Rover’s electronic tricks provide traction on the most unlikely terrain, and its genuine off-road ability differentiates it from all premium 4×4 ‘soft road’ rivals. But on the soft dunes, a camel is still better.

We pass a vast mountain of sand, which our guide tells us is one of the biggest dunes in this section of the Empty Quarter. We climb it and look, with awe, at the scenery – the sand stretches for miles, a sea of stormy golden waves, the sand patterns wonderfully and delicately symmetrical, formed by the wind. We can see nobody, no houses, no trees, just peaks and valleys of sand. We listen hard but can hear nothing apart from the distant breath of the wind.

Ubar, they say, has been found. But as I stare into the nothingness I can’t help but wonder whether those magical golden pillars still lie out there somewhere, buried forever in this sea of sand.