► Gavin Green drives Jag’s only supercar

► Flat-out in the 212mph Jaguar XJ220

► An archive gem from CAR+

It’s fitting that the last of the supercar monsters should also be the biggest, the fastest, and certainly the most striking. Appropriate, too, that this, the most expensive of them all, should be the best.

There’s little doubt that the Jaguar XJ220, deliveries of which have just started from new Bloxham factory in Oxfordshire, has its rivals comfortably covered in just about every department. On-road presence? I’ve never driven a car that turned more heads. Svelte styling? Have you every seen a more beautiful front end, or a more shapely profile?

Top speed? I was at Nardo when it recorded a genuine 212.3mph, in production trim. That puts it comfortably ahead of the Diablo and the Ferrari F40. The plug-ugly new Bugatti EB110 has just allegedly whizzed around Nardo at 212.5mph. But the Bugatti is still to be homologated for the road and deliveries won’t begin until September at the earliest, so it is palpably not a current production machine. Of the cars on sale now, or at any time in the past, the XJ220 stands supreme, and easily so.

To boot – and this is what really differentiates the XJ220 from most Italian exotica – the British car is extraordinarily comfortable. It’s quieter than you’d think, deft riding, and civilised. Jaguar’s old grace with pace motto is honourably maintained. Here is a 200mph monster that could fusslessly transport you, and friend, to the south of France.

It’s also roomy – not always the case with mid-engined supercars. There’s decent legroom and plenty of shoulder-room, a partial upshot of the car’s massive girth – 7ft 3in across the beam. Which, incidentally, makes it the world’s widest production car. It also means the XJ220 is physically unable to fit through London’s traffic width restrictors.

The Jag is massive in just about every other way, too. It’s over 16ft long, just a tad shorted than the XJ6 saloon, which can seat three extra people and has a much bigger boot. It weighs just under a ton and a half. Its quad-cam 24-valve 3.5-litre V6 twin-turbo engine, based on the 1990 XJR-11 sports car racer’s, pumps out 542bhp. That’s the mightiest output of any production road car.

Finally – and perhaps most massive of all – the XJ220 costs £415,544 in the UK, inclusive of taxes. There’s never been a pricier new production car. All 350 to be built, between now and the end of next year, have been pre-sold. I drove production car number 001. No surprise, perhaps, but it’s eventually going to Jaguar Sport boss Tom Walkinshaw, who is personally testing the first 10 cars off the line. Walkinshaw comes with me when I spend a morning driving the XJ220 in and around Oxfordshire.

Open the driver’s door, by the dainty little semi-circular catch at the door’ edge. It’s light, and so is the aluminium door itself, as it swings through its disappointingly small arc. As it is, you almost have to squeeze between the door and its jamb, into the leather-bound driver’s seat, thickly padded and side-bolstered, and with ‘XJ220’ etched into the squab. Your hips are cupped by the seat, and so are your shoulders.

You sit straight ahead, pedals and four-spoke leather-lined black Nardi wheel both beautifully positioned. There’s none of the askew nonsense that plagues all Italian supercars, the new Diablo and 512TR just as badly as the old time Lambos and Ferraris.

The base of the windscreen, sharply angled and subtly curved, finishes a long, long way ahead of you, the other side of a vast dash. The top of the dash, and the binnacle itself, is dark grey, less reflective than the lighter grey leather which swathes the rest of the cabin. The Connolly hide are beautifully trimmed and stitched. The finish is less impressive on top: the glass roof, which makes the cockpit impressively airy, is bordered by plastic, which feels and looks tacky. Column stalks, and the dash switchgear, are all Ford sourced, and none the worse for that. The instruments themselves are bespoke.

There are plenty of them – more than on any other car of recent memory. In the main binnacle you’ll find the big central speedo, which runs out of numbers at 220. It’s flanked by a similarly sized tachometer, red-lined at 7500rpm. Also housed in front of the driver are the fuel level, oil pressure, oil temperature and water temperature gauges.

The door houses four more instruments which, with the door shut, sit just the other side of the big side vent, all angled to the driver. Here you’ll find an analogue clock, turbo boost pressure gauge, ammeter and – a new one for me on a road car – a gearbox oil temperature gauge. These door-sited instruments are, to all intents and purposes, useless, although they are an intriguing gimmick. You would never look at the door to check the turbo boost when you’re storming along in an XJ220 – if for no other reason than that you wouldn’t dare take your eyes off the road.

The centre console, with the shortish gear leaver perched on top, is high and slab-sided. you’ll be resting your left elbow on that when the driving starts. Headroom is a bit tight for very tall people, adequate for those up to about 6ft 2in. The steering wheel – non-adjustable – is higher than the saloon car norm, but nicely situated all the same.

Turn on the ignition using the key, and a red light on the dash to the right of the steering wheel glows. That’s the starter button. Push it, and a rattly, rather weedy noise emanates from the little V6 over your shoulder. It comes as quite a schlock, that noise. you expect a Bengal tiger but get a tabby playing with a bag of bolts. There is talk of changing the exhaust to improve the low-rev note. The front engine mounts will definitely change before the first customer car is delivered, to overcome a particularly nasty boom and resonance at 2000-2500rpm, common revs when tootling through town.

The steering, non-power assisted, is not particularly weighty, despite the vastness of the front rubber. Engage first gear, notchy and inclined to balk as you move the leather-knobbed lever out of the neutral plane, feed in some revs with the heavy throttle, let out the meaty clutch. The car moves forward meekly, happily pussyfooting along at low engine revs, proving surprisingly tractable.

Out onto the public road, forward visibility is panoramic, and side vision is good, despite the shallowness of the glass. Rear vision is better than on some other mid-engined monsters, and a treat to behold, for the rear-view mirror gives you a glorious view of the top of the engine, and of the crisscross roll-over bar covering it. Rear three-quarter vision is restricted, due to the lowness of the seating position, and the titchiness of the rear side windows, teardrop shaped and almost teardrop sized.

Into second and third – it’s a conventional five-speed box, with top out on a dogleg. It’s a firm gearchange, and quite long of throw, as well as slightly notchy. But it’s not difficult to master. Nothing about driving the XJ220 is difficult. It’s heavy, yes. Yet it’s docile and responsive, even at low speed.

Like all the best performance cars, this one shrinks as the speed builds. You always know, deep down, that you’re wearing a set of XXL clothes. Yet, when going fast, the XJ220 feels small. Helped by its much better driving position, its superior visibility, and by its quieter and less tiring demeanour, this is an easier car to punt hard on long runs than any seriously fast supercar rival.

A few miles down the road, it’s time to start digging into the XJ220’s power reserves. Mosey along, just 2500 revs on board the tacho, in third gear, and then push the loud pedal hard. The engine waits just a fraction of a second as it draws breath. Then there’s a massive kick in the back as the turbos energise the engine, the crank starts to race around the rev band, and the engine throws off its tabby cat disguise and really starts to sound like it’s at Le Mans. And while all this is going on the road ahead seems to get narrower (just as the XJ220 does at speed), the horizon is pulled closer, you feel like you’re flying a foot above the road rather than riding on it – partly because the chassis sorts out road irregularities taken at speed so well – and if there’s another car on the road going your way, you’ll be on its rear bumper more quickly than you’d have imagined possible.

Brake hard – that’s really heavy work – and you can feel some graunchiness in the pedal, the upshot of the pads working on cross-drilled discs. The pads are racing car-hard – not surprising, when you consider that they are supposed to halt progress from 200mph. That also means they are too firm, too lifeless, for slow motoring. Only when tanking on does the middle pedal come to life.

Except under hard acceleration, the car is quiet up to about 90mph. Road noise is well suppressed, unless the surface is particularly abrasive. Engine noise is distant, helped by the high gearing. Three and a half thousand revs in fifth equals a very relaxed (and very easy) 100mph. You can still talk quite easily to your passenger at this speed, although voices are starting to be raised.

Only when the turbos do their bit, and the car is accelerated hard, does the engine truly get noisy. It’s boomy at 2000-25000, docile and neutral sounding up to about 4000, and increasingly busy (yet always smooth) above that, right till the 74000rpm cut-out. Pity, it’s not a bit more musical. Whereas a Ferrari serenades you when the revs build, the XJ220 merely makes a noise, albeit a meaty one under hard acceleration.

The most surprising aspect of this most civilised of road racers, is the ride. The XJ220 moves over knobbly tarmac with extraordinary dexterity. It doesn’t arrogantly ride roughshod over poorly surfaced roads, swatting the tarmac and spanking the passengers as most solidly sprung supercars tend to. The big Jag rides urban blacktop better than many sports saloons, never mind supercars. It caresses, not cudgels. It’s a little lumpy at times – what do you expect from those vast tyres? – yet is much more supple than any other super car of my acquaintance.

The suspension is double wishbones all round, machined from solid aluminium at the front and at the top rear. The lower rear wishbones are pressed steel and, as they’re in the flow of the rear ventures, are specially shaped to help the ground effects. The wishbones are mounted to the uprights by racing car-like rose joints, to improve response and reduce slack. On the chassis, they are rubber-mounted, to help isolate the wheels and the road noise.

The tyres are bespoke Bridgestones, 255/45ZR17 at the front, 345/35ZR18s at the back. The vast alloy wheels have big centre-lock nuts. There’s no spare tyre; there’d be no point in offering one. The wheel brace needed to undo the centre-lock wheels is so vast that it could never be carried in a boot. There’s no ABS, deemed inappropriate on such a car.

It’s impossible to evaluate the handling on public roads. Fact is, it’s almost impossible to evaluate the car properly at all on British blacktop. The XJ220 is just too fast, its roadholding too secure, to be taxed on puny little roads that other cars use. The grip, of course, is prodigious. Yet the Nardo exercise (see accompanying story) revealed a slight predilection for safe, controllable understeer, unless the rear end is provoked. And, with 542bhp to do the provoking, you can get the tail out very easily, if you’re stupid enough to give it welly halfway around a corner.

Standing-start acceleration is also phenomenal. According to a Jaguar test driver I met at Nardo, 0-60mph comes in 3.7 sec, 0-100mph in 7.5. Drive the XJ220, and you’ll believe it.

Like all wide-tyred supercars, the XJ220 does tend to follow the road surface blindly. If the camber falls away to the road’s edge – which is usual – the car will always want to fall off the road under heavy braking. Steering correction is needed to brake straight and true.

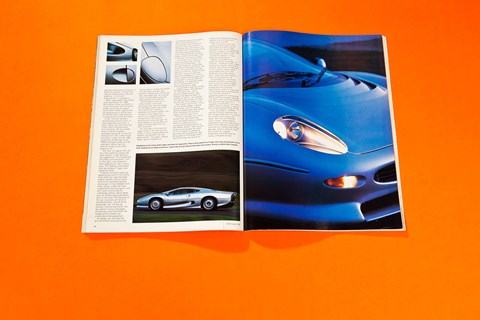

After my stint with Walkinshaw, I asked him if could just pore over the car to appreciate it fully. The XJ220 is one of the few supercars that is almost as enjoyable to look at as it is to drive. Come upon an XJ220 for the first time and you see pure automotive sculpture, a Rodin on wheels, a shape that may be impractically long and wide but – to hell with practicalities – is gorgeous.

When Jaguar Sport was asked to productionise the 1988 Birmingham Show car XJ220, it could not tamper with the basic shape, penciled by Jaguar stylist Keith Helfet. Jaguar had the good sense to realise that the XJ220 had to stay beautiful, if it was going to stay desirable.

In fact, the car has been shortened by almost a foot, is now marginally less wide, is much lighter (by more than half a ton), and is mechanically much simpler. The four-wheel drive of the Birmingham prototype has gone; so has the massive V 12. Yet it looks much the same. In fact, put the 1992 production XJ220 next to the 1988 prototype XJ220, and the road-goer rather than the podium exhibit is the more beautiful car.

The nose, so Jaguar-like, yet so unlike anything Jaguar has done before, is both graceful and aggressive. The headlamps are pretty and innovative. Turn on the lights, and instead of them popping up, their covers drop. This feature is borrowed from the stillborn F-type, also styled by Helfet.

A dainty little grille opening, growling cat motif in the centre, helps feed the nose-mounted engine radiator, the oil cooler and the air-conditioning heat exchanger. A much deeper and wider scoop, under the nose, supplements the cooling air, and also starts controlling the underbody airflow, which helps give the XJ220 a ground-effects grip on the road. The floorpan of the car is actually as flat as a breadboard but, just aft of the passenger cell, it kinks up sharply, channelling the air into two distinct venturi passages, divided by a vast boat-keel-like wedge which cradles the underside of the powertrain.

At speed, you can feel the ground effects sucking the car tarmac-bound. Follow the XJ220 on a wet day, and two vast plumes of spray spit up from the time ’80s to hit the road, the rear, like water jets. On a dusty road, dirt and debris are also jet-propelled out of the tail.

Every panel on the car is softly curved, none more enticingly than the front wings. All the body panels are made from aluminium, machine-pressed, but hand-finished. The chassis is also made from aluminium, supplemented by honeycomb in the central structure for extra strength. For extra rigidity, a racing-style roll cage is incorporated into the main structure.

The only part of the steel roll cage visible is the rear section, where it criss-crosses above the engine, just beneath the vast glass screen. The glass, steeply raked, gives onlookers an unhindered view of the engine, deliciously handsome, if surprisingly small. Featuring beautiful cast alloy plenum chambers and cam covers, the V6 seems lost in the vastly long and wide bay, bordered by silver heat shielding. The twin turbos, sited low on either side of the bay, are clearly visible.

At the rear, you’ll notice the fairly discreet wing, see the small and shallow boot – big enough merely for a briefcase and those matt black Ferrari-like slats, to my eyes the only ugly feature on the car. Peep through the slats, and you’ll see that there’s no bodywork in front of them, merely exhaust pipes and a transaxle in line and behind the engine. It’s specially made by FF, better known for its pioneering work in 4wd.

I could look at that car all day, but Walkinshaw – who devotes all morning to me – has a business appointment near Oxford He wants to take his XJ220, for which I can’t blame him. We shake hands, he starts the V6 and, with a wave, is off.

Pity it hasn’t got a V 12, I think, as Tom whisks away. It would sound nicer, and the engine would probably look even better. And, somehow, the purrfect Jaguar should have a V12.

I’d like a narrower car, and a shorter one. No matter how small the XJ220 feels at speed, there’s no denying that it occupies more ground than a two-seater should. Tight country roads are physically too small for it to unleash its awesome ground-covering potential. Not being able to fit through traffic restrictors may also prove an unwelcome embarrassment for owners, many of whom will surely live in London.

Fact is, the car is just not suited to British roads, or for that matter to public roads anywhere else. It’s too wide, too fast, too valuable, no matter how comfortable its cabin, how civilised its chassis, or how pleasing its demeanour.

Rather, the XJ220 is an expensive piece of garage – or museum – sculpture, sure to give pleasure to anyone invited for a viewing. And, when the weather is nice, and the owner wants some expensive thrills, the XJ220 will assuredly deliver them. There has never been a more thrilling driver’s car.

As probably the last of the 200mph monsters conceived back in the let’s-have-a-good-time ’80s to hit the road, the XJ220 also has historical significance, even if it may have no real engineering relevance. I can’t see the likes of it appearing again for a long time. The mood has changed: people just don’t covet cars that are this fast and this big anymore. I suppose it’s sensible, but it still seems rather a shame, a sign of the increasing blandness of life.

True, the Bugatti, oddball-looking Yamaha supercar and the intriguing McLaren F1 are on the horizon, and may all be faster. But they are different sorts of cars – technological statements from tiny specialists, rather than 200mph sculptures from the car industry big names. Besides, none is likely to have the cachet of a Jaguar. Especially one that looks so lovely, and goes so fast.