► Bulgin’s American drive in a red Cadillac

► Hunting the man who sold Elvis his Caddy

► Classic adventure drive from 1992

When I’m driving in my car and a man comes on the radio, and he’s telling me more and more about some useless information concerning how – get this – Charles Darwin was wrong, I start to wonder. Two long days into a hunt for Elvis Presley, trudging through the middle of Tennessee with beige rain lashing down between flash flood warnings that are growing ever more dramatic, this lazy drawling AM radio fundamentalist starts to explain how the entire theory of evolution is up the creek. Send a couple of bucks to receive your personal copy of Darwin’s Enigma: Fossils and other problems; join what Mr. Glib calls the ‘growing ranks of evolution disbelievers’.

Am I really here? Cruise-controlling up to Memphis in an electric strawberry Cadillac Allante with stereophonic religious weirdness booming out over the rain-splash and the wiper-flap? Oh yes: this IS real enough.

Elvis Presley bought over 100 Cadillacs during his lifetime. You can forgive a man a lot of lousy movies knowing that. On 3 September 1956, Elvis gave his mother Gladys a pink Cadillac. She couldn’t drive, so remained on the driveway of Graceland, his Memphis home, as an immobile chrome and vinyl temple to the American dream. So I will take a new Cadillac to Memphis with a simple mission in mind. I will find the man who sold Elvis his cars.

There’s a more personal aspect to this pilgrimage, too. I’ve wanted to go to Memphis for the past 10 years. Memphis is rhythm and blues ground zero: I could spend the rest of my life listening only to records made in that city.

So the Cadillac Allante was, to start with, just a means to an end: Elvis had his Caddies but I would have gone to Memphis on a bus. But now, two days and 700 miles of Interstate closer to Memphis, with the sky a gelatinous grey and rain pulsing down, I like this car.

For one thing, it looks terrific: short, squat, muscly, big wheels pushed tight into the corners. The Allante makes a BMW 850 seem overdressed. Then again, this is a Pininfarina body, designed and made in Italy before being air-freighted to Detroit in the world’s longest – and stupidest – production line. There’s a 4.5-litre V8 mounted transversely upfront, easing out a cool, easy backbeat, a huge boot, a spacious cockpit.

This is, after all, a grand tourer. Up north from Florida, across Georgia, into Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama and back to the sun-scorched citrus groves and Mickey Mouse-everything of Orlando. Two thousand miles lined with scarred charcoal asphalt, 10-hour days running 10mph over the speed limit and dodging radar behind rumbling rigs from Peterbilt, Kenworth and Mack. Days spent mind in neutral as the two-lane grey-top unfolds ahead, pounding the superslab with the Caddy purring and the CD pumping.

The first stop had been Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame. I wanted to confirm that Marty Robbins’ pink safari suit, embroidered with rainbows of hummingbirds and flowers, came complete with matching cowboy boots. It does. I also wanted to see Elvis’s gold Caddy.

A 1960 Cadillac Fleetwood 75 limousine, flecked in white pearl paint, with the brightwork gold-plated, the interior a boudoir of white vinyl and gold tufts, the headlining home to a slew of Evo-Stuk gold records. George Barris – understated genius behind the Beatnik Bandit, the Munster Coach, the Monkeemobile – customised this Caddy, installing the TV, the record-player, a gold electric shoe-shiner and gold ice trays in the fridge which could cube water in two minutes flat.

And there it was, roof raising and lowering by electric motors, so us gawpers could not fail to appreciate every last 18-carat detail. Outside the Hall of Fame, the daylight seems almost supernaturally harsh and across the street on Music Row lies the Conway Twitty Record Store, the Ernest Tubb Record Shop, a Hank Williams Junior shop, a Randy Travis shop, and an emporium owned by George Strait: the Barbara Mandreil Christmas Shop is, sadly, closed.

This is Music City USA. Singing stars owning record stores. American kitsch, American blue-collar dreams. And, maybe, with Elvis apparently receiving 19,000 drug doses from his personal physician in the last two-and-a-half years of his life, American gothic, too. Have a nice day, y’all. Can I think about that?

Two hundred and fifty miles to go to Memphis. Interstate driving has a life, a rhythm all of its own. Pull up at the Truck ‘n’ Tummy restaurant in a Tennessee backwater and you’re instantly marked as an outsider even though a $56,000 Cadillac in a park full of trucks is an in-your-face calling card – because you’re the only person perusing a menu (‘Hamburger sandwich plate, 1121b pure beef $389’) who isn’t wearing a baseball cap.

A stainless-steel cooking area gleams behind the formica bar, a skinny kid with a paper hat and insistent zits flips eggs over easy, sunny side up, whatever you want. This is a nation on the move: truckers with beer-bellies chew coffee and read the paper. Conversation is quiet, monosyllabic. A quarter in the jukebox gets you George Jones singing Call the wrecker for my heart.

Memphis looms as a sprawl of freeways, six-lane babble and peek: you scan the billboards, the insistent roadside graffiti, of modern America. Your first port of call is 1413 Getwell Road. Elvis lived here from mid 1955 to May 1956, before Graceland, before the music, before the madness.

Elvis lived in a Chief Auto Parts store. Check eh address. It’s right. Go inside. A couple of old guys – check shirts and turkey necks – are buying parts for a pick-up. The shop is bright, airy, modern. The guy behind the desk says no, he didn’t know Elvis lived here. He doesn’t give the slightest indication that he might think you’re bonkers. Then again, the store’s only been open for 18 months and he’s from San Diego, anyway. As you leave you notice a binful of aluminium cylinders. These are gizmos which make your indicators play a melody in the cockpit as you signal. The tune is Love me tender. Do you believe n psychic coincidence.

This is not a good neighbourhood. This is the America Europeans don’t often see. Driving a reed Cadillac around here is treading thin line between thoughtless conspicuity and fiscal obscenity. You find Humes High School, which Elvis attended from 1949 to 1953. Black kids stare out of the windows. They don’t say anything. The Cadillac says enough.

The houses are lousy, clapperboard affairs, old car seats sprawling across the front porch, Detroit antiques nuzzling kerbside on flat tyres. Negro children play in the street: teenagers hang around in sullen groups on the sidewalk. There’s no reaction to the Cadillac, to you, just studied the indifference.

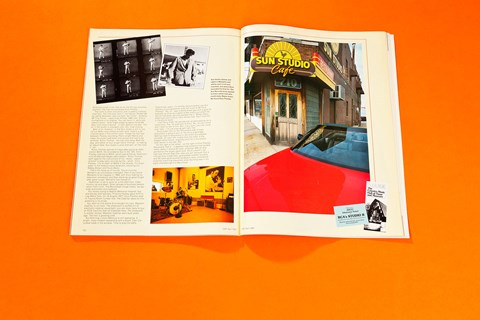

Then suddenly, you arrive at a redbrick building on a street corner, opposite a Domnio’s Pizza and just down from the Carburetor ship. Sun studio. Where rock ‘n’ roll was invented; where global youth culture was kick-started. Surrounded by parking lots, Sun studio sits alone. Nondescript.

Sun records was owned by Sam Phillips who once said, ‘If I could find a white man who had the negro sound, I could make a billion dollars, ‘a sentence which says as much for the social reality of living in the American south in the ’50s as for the Phillips business acumen. The man he found was Elvis Presley.

The room is small and white, with a greeny linoleum tiled floor. The first-ever rock ‘n’ roll record, Rocket 88 by Jackie Brenston, was cut here. Ike Turner – formerly Mr. Tina Turner – used to be Phillips’ A&R man. Elvis’s microphone is on display. You can touch it. Jerry Lee Lewis’s piano – what finger-popping agony those 88 keys must have endured – is tight against one wall. The air in the studio is strangely cool, dry, slow-moving.

Best of all, however, is that Sun studio is still in use. IJ2 cut When love comes to town here: there’s a 24channel desk in the control room. Forget the fact that between Presley recording That’s alright Mama and today the studio had fallen into disuse and had to be restored. Rufus Thomas – the man who sang Walk the dog and father of soul singer Carla Thomas – is making an album here. Sun studio is alive and well: all hail rock ‘n’ roll.

Rufus Thomas spends his days dee-jaying at radio station WDIA. He recorded at Sun in the ’50s. Elvis Presley listened to WDIA, which was billed as ‘America’s only 50,000-watt Negro radio station’: Rufus Thomas went against the instructions of his – black – station director to play early records by the – white – Elvis Presley. I try to listen to WDIA in the Allante. It’s stuck down in the medium-wave doldrums, churning out Bobby Brown and Paula Abdul.

That’s the hang-up of course. You’re cruising Memphis as a European nostalgist. Part of you wants Memphis to be trapped in 1968, with Elvis making his television comeback and Stax stacking up great single after great single. Memphis has moved on.

Downtown is eerily quiet on a hot afternoon. Cabs murmur up and down. Small groups of business people return from lunch The Mississippi chugs slowly, syrupy-wide and brown and laidback.

You mosey along to Baptist Memorial Hospital, big and blocky and faceless. Priscilla Presley gave birth to Lisa Marie here. On 16 August 1977, Elvis Presley died in Trauma Room number one. The Cadillac takes all this pottering in its stride.

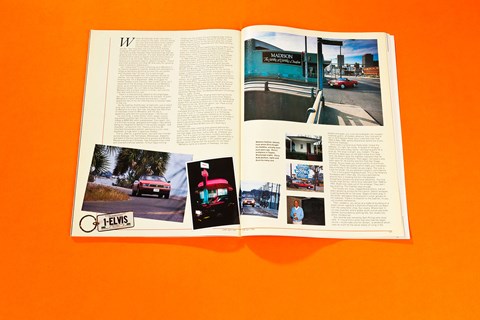

You want to find where Elvis bought his cars. Madison Cadillac is no more. The showroom is stuffed full of electronic medical equipment; you are more likely to buy an ECG machine than an Eldorado here. The showroom is locked, bolted. Madison Cadillac went bust years ago. The trail is growing cold. But Schilling Lincoln-Mercury is still operating. A bright, clean modern dealership with a black Town Car tucked sleek in the window. Time to play the daffy Englishman again: I’m terribly sorry to bother you but did any of you gentlemen ever sell a car to Mr Elvis Presley? ‘No, sir,’ says a beefy black guy with a gold ID bracelet as thick as a grass-snake and a suit which fits like he had been vacuum-packed into it. ‘Mister Percy Kidd sold cars to Elvis. He’s retired now. You’ll find him in the phone book.

I call Percy Kidd. He sounds old, as bemused as he is suspicious. Yes, he sold cars to Elvis. No, he can’t think why I want to talk to him. But, if you want, you can come over later – I’m just playing golf right now.

Percy Kidd lives on the Graceland side of town. Graceland is ground zero on the Elvis pilgrimage. Getting close to Graceland is like entering a parallel universe. On your left, visible from the road, is the elegant white house, originally built for a successful local doctor in the late ’30s.

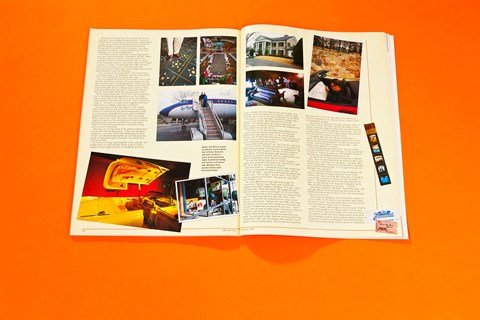

On the right of the street – on the right of Elvis Presley Boulevard, that is – it appears that someone has landed, rather deftly it should be said, a Convair 880 jet and painted all the shops spam-pink. Elvis’s plane’s call sign was Hound Dog One; later you will discover that a circular blue suede bed, gold-plated seatbelt buckles and 24-carat gold-ducted hand-basin were considered essential traveling requisites when the King was in his eight-cheeseburgers-a-day phase.

Graceland is elegant from the outside and, for the most part, often disappointingly so within. There are stories that Priscilla Presley had the place redecorated in pale colours before Graceland became a shrine to 600,000 gawpers a year and turned Elvis Presley Enterprises into a $150 million company: if you were expecting the maroon-and-gilt bordellosity of Elvis’s dog-days, you will be disappointed.

The house is small. Detailing is reassuringly glitzy – why use a light fitting when a chandelier will do? When in doubt, daub on the gold – and leads you to the inevitable conclusion that Graceland, with its veined mirrors and pale carpets, long leather sofas and fringed curtains, is, in fact, the prototype for a ’90s business hotel. Put a minibar in each room and make the occupants wear a Dymo-label name badge and you’d be hard pressed to spot the difference.

Until you get to the Jungle Room. This is the rock’n’ roll Sistine Chapel. I’ve wanted to see the Jungle Room since I first read about it a dozen years ago.

Elvis purchased the furniture for his den in 30 minutes flat and, thankfully, it shows. The chairs appear to have been pirated from a Johnny Weismuller Tarzan film: big, tree-trunky leathery commodes. Tables are knurled out of gnarled wood. Ethnic artefacts which look as if they were yours free when you sent in 10 special coupons abound. The carpet flexes like squidgy green moss.

And it hangs above your head, too. I ask the guy why this is, thinking that perhaps by the time the Jungle Room came to be in the ’70s, Elvis was so disoriented that he couldn’t tell floor from ceiling. ‘That’s a California thing, sir,’ he says in a voice which suggests you have been privy to a deeply meaningful revelation.

Elvis actually recorded two albums in the Jungle Room (from memory they were This is the house that tack built and Priscilla, this damn hamburger’s cold) because being enveloped by muzzy green nubbytex apparently improved the acoustics. After the Jungle room, a pool room with 750 yards of eye-searing the fabric draping the walls, a 24-carat gold piano and a violently yellow-and-blue basement where Elvis could watch three TVs simultaneously beneath a mirrored ceiling, seems a touch restrained.

Pausing only to read some of the graffiti etched hard into the wall outside Graceland – it falls into two basic categories: ‘Lars and Ulrike from Goteburg love Elvis forever’ and detailed speculation on just how good the owner of Graceland was in the sack – you head off to visit Percy Kidd.

His house is a long, low bungalow in the suburbs. The Caddy purrs to a halt outside, where a guy in a blue sweater and pink golf trousers is sweeping up. Percy Kidd is deeply tanned, a walnut face and a deep, slow, Southern voice that takes lots of pauses. Later he says he is 83 years old. He has lived in Memphis since 1919. The house is cool and dark. A television plays soap operas in the corner. Mrs Kidd watches from the kitchen. Percy Kidd lights up his pipe and chats. He starts slowly. He doesn’t quite believe that someone has come 4000 miles to talk to him.

‘l met Elvis in ’56. He had those long sideburns. He usually wore blue jackets and so forth. He was just beginning to get popular then, in ’56, and he came through the lot and there were two or three little girls out there, and he walked up to one of them and kissed her on the forehead and she fainted.’

Percy Kidd starts to warm up. ‘The first car I sold Elvis was a ’57 Lincoln. That was just before he was going on the Ed Sullivan Show. That was his first appearance – do you recall it? Then he got to Florida, he had a show to do in Miami, and the teenagers got ahold of it and marked it all up with lipstick, and he turned around and sold it and bought a white ’56 Continental.

‘He had that white Lincoln for a number of years. I guess over a period of 20 years that I knew Elvis, I sold him 75 or 100 cars – often for his friends.

Mrs Kidd butts in. ‘I remember that at two o’clock one morning, I answered the phone, and he said, “Let me speak to Mr Kidd” – you know how formal he always was – and I said, “He’s in bed,” and he said, “This is Elvis, Will you get him out of bed?” That was the only time I ever talked to him.

‘He came down there that night and bought 12 Lincolns for friends,’ says Percy, with a smile that suggests this didn’t happen everyday. ‘This was – what year was that? Must have been ’76, maybe the year before he died – and he just bought ’em for his friends.

‘He’d call me here or at the garage. He called me one time from Germany when he was over there in the service – I had sent him a brochure on a new Lincoln that was coming out. I believe this was 1960, they were coming with a new Town Car. He got that brochure and a couple of days later he called me and said, J ‘l want you to have me one of those made, and have it ready for me when I get home from service,” which I did.

Mister Percy Kidd looks sad as the memories stroll back. ‘He was quite a boy. Anytime he’d buy something he wanted it right now. He always liked a black Lincoln: black or white, mostly black. He just wanted everything that went with it. He never did specify any particular thing he wanted on a car. Most of those Lincolns come fully equipped, anyway.

‘l was sitting out there on the steps one day, talkin’ to him. And he said, “Mr Kidd, I got all the money in the world I could ever hope to spend, but I’m just miserable. I’m just lonely, I can’t do anything I want to do.” He was a really lonely boy. He had all these people around him, but in my opinion he was just plain lonely.

‘He always dealt with me. He was a fine boy.’ A pause. ‘Of course, the last couple of years of his life he was an entirely different person. He got onto whatever he was – pills or whatever it was he was takin’ – and kinda turned against his friends.’

Percy Kidd pauses and then grins. ‘You remember that little Pantera?’ Yes: a De Tomaso. ‘It was just as fast as lightnin’. That thing would run 150-160mph. And this was after we had stopped handling the car.

He called me one day and said he wanted a Pantera. I said, “Elvis, we don’t have that car anymore. But I can get you one I can have it in two days.” He said, “Weil, I want it right now.” I knew of a fella who had a used one out on the lot and Elvis said, “If it’s a good one, go out and see if you can get it.

‘I went out there and the damn thing, the battery was dead, it had been sitting out there for two or three months, and wasn’t running. We finally got it running so could take it out there to show it to him. He said, “I’ll take it.” He bought the damn thing right there on the spot. He was driving it one day and it stopped. So he took his pistol and shot it fulla holes….’ A smile.

‘He always called me “Mr Kidd”. Sometimes after I got through work I’d come out and play pool with him at Graceland and he was a friend of mine. He sure bought a lot of cars from me.

Percy says his goodbyes and the Cadillac heads out of the ‘burbs. In one-way the trip had been dominated by the Elvis myth: you have been ghost-hunting and the end has made the means almost irrelevant.

I stop in Tupelo, Mississippi on the trek south. A white wood shack stands in an ordinary street. Elvis’s dad, Vernon, built it. Two room-simple: Elvis was born there. One glance at 306 Old Saltillo Road explains the gold-plated seatbelt buckles and plumped-cushion excess of Graceland. It makes an obsession with chrome-heavy Cadillacs and low-riding Lincolns easier to understand.