► Richard Seaman, the first Brit GP driver

► Killed on the eve of World War 2

► We interview biography’s author

What a terrible time to publish a brilliant book. Richard Williams has written wonderful books vividly telling the stories of Enzo Ferrari, Damon Hill and Ayrton Senna. But this latest one tops them all for drama, insight and casting fresh light on old events.

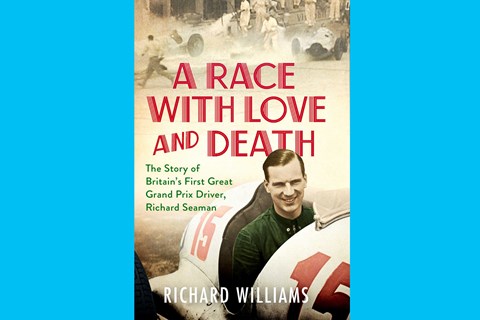

If “A Race with Love and Death” gets overlooked because of the health horror engulfing the planet, that would be a terrible shame. Especially as a lot of us suddenly have time on our hands to sit down and immerse ourselves in the tale of Richard Seaman, Britain’s first great Grand Prix driver, as the subtitle calls him, who famously won the 1938 German GP in one of the Hitler-backed Mercedes Silver Arrows, and died in a crash in 1939.

Best books for car fans

Seaman was an ambitious British racing driver who excelled in domestic events but looked to Germany for the factory drive that would enable him to become a Grand Prix winner. This was in the 1930s, so with the benefit of hindsight we wonder what he was playing at. Was he a Nazi sympathiser? An appeaser? An empty-headed aristocrat or hedonistic playboy indifferent to the horrors of Hitler’s Nazis? It’s easy to assume the worst, and that has done Seaman’s legacy no favours – something Williams puts right here, in a book that’s deeply researched but a compellingly easy read.

Williams told CAR: ‘The bones of the story are well known. I’ve known them since I was a schoolboy. But I thought it was worth trying to set the story against its social, cultural and political background as well as the sporting background.

‘A lot of people went for their usual holidays in Germany, or to the opera, in the mid-’30s, and thought this bloke Hitler’s doing a pretty good job. Everybody seems to be in work, they’re all whistling as they walk along the street very cheerfully, he seems to have rescued a nation that was a basket case. For Dick, the penny gradually dropped as he began to see what was really going on. But a lot of people didn’t for a long time, practically until the outbreak of war.’

For Williams, research was more than just reading old books and magazines. ‘There’s nobody left to talk to from that time, nobody left who knew him. I thought the only way really to tell his story in a richer way was to immerse myself in every aspect, go to the places he lived, where he was born, where he lived as a boy, where he lived in Germany, to go to all the schools he went to, to go to the places he raced, the place he died, the hospital, the church, not to mention the grave of course.

‘People were very helpful. The Mercedes archive is an extraordinary thing. They couldn’t have been more helpful. Miraculously, they have everything. You go there and you say have you got anything on the 1938 German Grand Prix, or any Grand Prix they raced in, they’ve not only got the tyre pressures and the gear ratios and the chassis numbers and the engine numbers, and what power the engine was pulling on the test bed before it was installed in the chassis, they’ve got the hotel reservations, who was getting a double room and who was getting a single room, and Neubauer’s reports, and in Dick’s file they’ve got all the letters and telegrams of condolence that came from all over Europe when he died. To hold in your hand a telegram from the Bugatti team in Paris is quite a moving thing.

‘I’ve known all my life that he was a terrific driver, and I admired him for that, but I had no idea what sort of person he was. I do think I came out of it with a reasonably convincing impression of what he was like. The longer I went on, the more the idea of him being a wealthy playboy fell away, and the clearer his real attitude, his terrific professionalism, his seriousness about the business of being a racing driver, came through.

‘Dick wasn’t happy to just race at Brooklands and Donington and stay within the British scene. His sights were firmly fixed on Continental road racing and Grand Prix racing, the top level.

‘Mercedes thought very highly of him. They hired him initially as a reserve driver and he had to persuade them that he was worth a start. I think if he’d won the Belgian Grand Prix, the race he was killed in, that would have established him once and for all as a top-line driver, a first-choice driver alongside [Hermann] Lang,’ said Williams.

‘[Rudolf] Caracciola was still a fantastic driver, but he was getting on a bit, and [Manfred] von Brauchitsch was always a bit wild. I think Seaman and Lang would have been the Mercedes drivers for the future, had not world events intervened.’

Seaman set a template still being followed today. ‘Only three British drivers have driven for the Mercedes Grand Prix team. One was him, the second was Moss and the third is Hamilton. They were all extremely different, from very different backgrounds. What they shared was a real driving ambition and a fantastically professional attitude. I think you can trace Moss directly back to Seaman. Seaman was the example for Moss’s generation. Moss is the one who took it most seriously. You’ve got to look after yourself, prepare yourself, not treat it as a pastime – it’s a serious business.

Best books for car fans

‘When he got to Mercedes Rudi Uhlenhaut, the chief designer, valued his feedback very much. I don’t think he got any feedback from Caracciola or von Brauchitsch at all. They thought their job was to get in the car, race it, and go and have a party. I think Dick was serious about pre-season training, and then practising and developing the car. And so was Herman Lang, who had come up as a Mercedes mechanic. The two of them bonded over that. They both wanted to help Uhlenhaut and [team manager Alfred] Neubauer keep the team absolutely at the top. I think Mercedes valued him from that perspective very much too.’

His crowning achievement was victory in the 1938 German GP, followed by his controversial salute on the podium; but before his full potential could be realised he was killed at Spa, and a huge wreath from Hitler at his funeral did nothing to help posterity look kindly upon Seaman. And then of course the war put car racing on hold.

Why write the book now? ‘It’s an idea I’ve been churning over in my mind for decades. I always thought there’s more to this story. Above all, I thought he’s somebody who’s slipped out of the national memory, undeservedly. There are obviously reasons for that: he died on the eve of a war in which a lot of young Brits died for a purpose in a different kind of way. Also, the question of him driving for Mercedes, and the whole Hitler wreath thing, tarnished his memory slightly in the eyes of some people.

‘He just kind of slipped away, in a way that Stirling Moss never will, for instance. I thought he needs to be restored to a position that he deserves. It’s a great human story.’

A Race With Love and Death – the Story of Britain’s First Great Grand Prix Driver, Richard Seaman, by Richard Williams, is published by Simon & Schuster

Check out more CAR culture features