► Retracing Donald Campbell’s steps at Lake Eyre

► Striking into the Outback in a Range Rover Sport

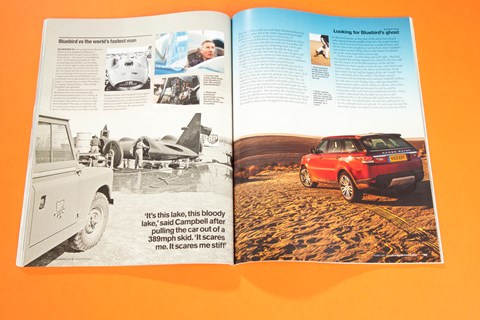

► ‘It’s this lake, this bloody lake. It scares me stiff’

In 1964 Donald Campbell brought a fleet of Land Rovers to Australia’s terrifyingly desolate Lake Eyre to support his attempt at the Land Speed Record. He almost lost his mind, his fortune and his life on that trip. Fifty years on, in the new Range Rover Sport, we go in search of his traces

Seen from space, or more likely from Google Earth, Lake Eyre looks like a vast white stain on the surface of Mars, and almost as inaccessible and inhospitable. It is the world’s largest dry lake, an expanse of mostly steely salt half the size of Wales, surrounded by sand and endless dry red Australian Outback dirt. It is a wonder of the natural world and has a unique, bleak beauty. No roads lead to it; just a track that often becomes indistinguishable from the flat, red earth. The risk of getting stuck in deep sand in temperatures that can reach 65 degrees, the speed with which the sun on that utterly featureless salt will disorientate you, and the almost complete absence of anything to support life mean very few people ever venture here. The indigenous Arabana people call it ‘the place of death’, and tell of a demon that devours those who come near it. The cattle farmers who eke a living around it never really think about it, or venture onto it. When floodwater fills it once a decade or so, tourists come to see the birds and pink algae that suddenly appear. But otherwise, as one of the first European explorers to see Lake Eyre said, it is ‘dry and terrible in its death-like stillness, and in the vast expanse of its unbroken sterility’. Staring at the satellite images of it from the safety of my home in Sussex, it was hard to imagine anywhere more alien and distant.

So why make the 3000-mile round-trip from Melbourne to a place nobody wants to go? Because 50 years ago this year, Donald Campbell did. He had already set a series of water-speed records and wanted to match his father Sir Malcolm by taking the land-speed record too. To do so, he built the Bluebird-Proteus CN7, one of the most extraordinary shapes ever to roll on four wheels. Intensely superstitious, he was convinced that the Bonneville salt flats were jinxed after he crashed the car there in 1960 and was badly injured. Drawn by Lake Eyre’s size, the fact that it hadn’t rained there for eight years, and the offer from Australian Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies of army help to build a track to the lake and a causeway out to the hard salt, Campbell brought Bluebird and his entourage here in 1963.

But being British, he brought the weather with him too. It rained, and there followed two summers of danger, frustration and acrimony with his sponsors and staff that nearly broke Campbell mentally and financially, before he finally broke the record with an act of bravery that answered at least one of the criticisms made of him.

At least he could count on his Land Rovers. The first one reached Lake Eyre in 1950, just two years after the marque was born, driven by conservationist and explorer Warren Bonython as he charted parts of the lake for the first time. He persuaded Campbell to come, and Campbell brought a fleet of Land Rovers. Two were adapted to prepare Bluebird for the return trip through the measured mile required by the FIA; others served to transport people and supplies, and would help get Bluebird off the salt when the storms and floods arrived.

Not much happens at Lake Eyre: not even oxidisation. I thought that if I went there I could do some land-speed record archaeology, and find some of Campbell’s traces. I would find more than I’d expected. And we needed a suitably epic test for this new Range Rover Sport, a car which its makers bill as a grand-touring SUV, and which ought to be able to eat up the vast mileages of Australia in luxury car comfort, but also see us safely over some of its most difficult, dangerous and remote terrain.

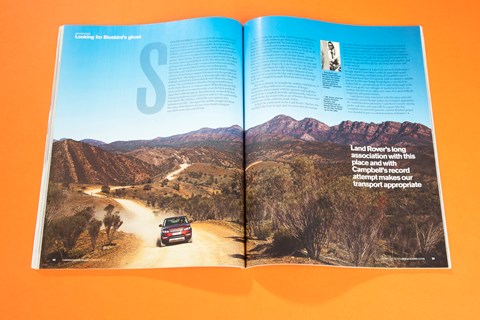

Land Rover’s long association with this place and with Campbell’s record attempt makes our transport appropriate. He would have been pleased by Land Rover’s recent soaring profits and sales, and especially by exports like this. Campbell was intensely patriotic, and the Bluebird project was intended in part as a demonstration of Britain’s engineering ability. Bluebird was built by the firms that were behind Britain’s then-booming car industry – BP, Dunlop, Girling, Lucas and Smiths, among others – and was financed at first by industrialist Lord Alfred Owen. Together they built a car of extraordinary technical far-sightedness, with data-logging, the beginnings of traction control and a head-up display, which Campbell disabled because he was superstitious about its green figures. Bluebird and my Range Rover Sport share four-wheel drive – ground-breaking then – and their bonded and riveted aluminium construction. And there are times when a Range Rover Sport, shorn of up to 420kg with that lightweight body, feels as if it is generating no less thrust than the 4100 shaft-horsepower of the Proteus gas-turbine engine Bluebird borrowed from the ‘whispering giant’, the Bristol Britannia airliner.

As a means of covering long distances, this modern Land Rover has more in common with an airliner than the rudimentary Series IIs Campbell used. He leased an Aero Commander to fly up to the lake from Adelaide. We have over a thousand miles to cover from Melbourne before we even start off-roading. Such a long drag looked a drag on paper, but the Sport’s cabin looks like it might make it tolerable. In some respects it’s better than the Range Rover’s: still elevated, but more enveloping, with the same proper luxury-car level of finish, but better ergonomics in places, like door bins you can actually access on the move and a gear lever, rather than the unfitting microwave-style rotary controller of the big car.

It’s also an infinitely better-looking car than the Tonka-like model it replaces, hiding well the fact that it’s longer and wider. It’s still 15cm shorter than a Range Rover but the difference feels way greater as we drive through the city. Parking the bigger car can feel like berthing a liner, but the Sport feels right-sized. Boot feels cramped, though: we’re fine two-up, but this ain’t no Disco.

Leaving Melbourne, the Sport just tears through the distances, straining against Australia’s low and tightly enforced limits. Ours is an early, pre-production car and an odd specification (left-hand drive, British plates, Middle Eastern mirrors) but Land Rover knows where I’m planning to go in it and is confident in its reliability. And after driving Sports with the adaptive dampers it’s good to give a ‘passive’ car a proper test. Plainly, long drags deep into the Outback aren’t going to test its handling much, but the ride is terrific: firmer than a Range Rover’s, connected but calm and comfortable. Everything gets better when you cut weight and increase stiffness, and you can sense the aluminium chassis letting the standard air suspension go about its business better. I wrote after the Range Rover’s launch that there could be no finer means of crossing the face of the Earth than the Range Rover, but I’m starting to wonder. You might be cynical about big, powerful SUVs but this is the kind of trip they nail better than almost any other vehicle.

We get out in Clare after a 600-mile day feeling fresh, and wake the next morning to views of its lush, damp vineyards shrouded in mist. We have only around 300 miles to cover to our next overnight in Parachilna, with a detour for some off-roading in the Flinders Ranges, but in that distance you see a continent unfold through your windscreen. From those cool, hilly vineyards, the landscape opens out first into fertile farmland, before the vegetation gets scrubbier and sage-coloured and the red dirt starts to show through. The plains get vaster and flatter, edged with the hills at first, until even these disappear, so that when the tarmac stops further north the track becomes almost indistinguishable from the dirt, and you feel like you’re travelling across that Martian surface you were looking down on from your computer screen. Our destination is Muloorina, the cattle station founded in 1949 by Eliot Price, grandson of a London policeman, and now run by his grandson Trevor Mitchell and his wife Cindy. It is 30 miles from the shore of Lake Eyre and the closest human habitation. It is where Campbell and his team made their base in the summers of ’63 and ’64, but it was already an extraordinary place before he arrived with his 4100hp car; an enterprise of scarcely believable numbers that just don’t compute for someone from a small island. With just two inch-and-a-half falls of rain each year, Trevor can keep 4000 head of cattle. But to generate enough vegetation for them to eat he needs a farm one-fifth the size of Wales. At nearly 1600 square miles, or over a million acres, only four English counties are significantly bigger than Trevor’s property, and it used to be bigger. The country is so vast that Trevor gets news of floods heading for Lake Eyre along its usually dry channels a month in advance, so he can park a car on the other side of the creeks surrounding his home, and can cross the torrent by boat and still get into the nearest town, 60 miles away. Gently spoken but built like one of his bulls, he wears a sweat-stained stetson and keeps a .38 revolver between the seats of his Toyota Land Cruiser ute. He does 30,000 miles each year in it without leaving his own property.

There’s a very admirable, nineteenth-century pioneering self-sufficiency at Muloorina. Speaking on a short film BP made in ’63 about that year’s attempt, Trevor’s mum Hazel described life in the early years there. ‘You’d go to get a saucepan to put the potatoes in, lift the lid and there’d be a snake curled up inside. You’d go ‘Aaah!’, grab your gun, shoot it, then you’d go on with the cooking.’ Cindy serves us a pile of steaks for dinner, and when we complement her on the meat she says, ‘she was a real handful, that one. I’d never have guessed she’d have tasted so good.’

We eat in the mess hall Price built for the Bluebird team, one of the dozen or so low buildings that once were home to 20 or more family members and workers. Now it’s mostly just Trevor, Cindy and their kids, and the mining surveyors and engineers who often stay with them. There are plenty more reminders of Campbell’s stay here. Up beyond the airstrip, first marked out with bleached camel-bones by the thrifty Price, lies the station’s boneyard. Nothing rusts here and space isn’t exactly at a premium so most of the vehicles the Prices have ever owned are still here, including some early Land Rovers which might have been used by Campbell, and the Blitz truck, which certainly was. Ancient even then, half a century ago it took five hours to haul Bluebird through 30 miles of sand to the Lake.

It takes us rather less time the next morning. Trevor first drove when he was five and I have never ridden with anyone who copes so instinctively with such poor conditions. The old Toyota just surfs through it all at speed, but behind us the Range Rover is easily keeping pace. Driving it back later the Sport does that odd thing that Range Rovers do, morphing from luxury vehicle back into an old Defender, because its fundamental capabilities are the same.

You don’t just need a four-wheel drive here; you need to know how to drive it too. Trevor tells me about the French tourist he found near-dead from dehydration by the side of the track to the lake after he’d abandoned his bogged off-roader; Trevor later drove it out just by dropping the tyre pressures and putting the diff locks in. People still occasionally try to drive on the salt despite a ban by its Aboriginal owners and the risk of getting stuck in the foul black gypsum sludge by the shore.

Trevor is occasionally called to pull cars out. ‘It can take days. I charge them plenty. But next time I might just leave it there.’ If you choose to ignore local sensitivities and the warning signs – like the camel whom not even nature’s four-wheel drive could save and whose bleached skeleton lay in the mud, spine above the surface, legs pointing straight downwards – maybe you deserve to lose your car.

No danger of that for us. Trevor has lived here for all his 54 years and never once driven on the salt. So neither will we. Given the consequences of getting stuck, it feels quite risky enough taking the Sport through the deep sand approaching the lake, but with the pressures dropped and the Terrain Response system in Sand mode it feels more capable than those old Defenders, and displays a confidence at odds with the treachery of the ground beneath.

When you crest the last dune and finally get your first view of Lake Eyre, the distance and effort suddenly seem trivial. There are few views like it on Earth: just a pure, clean line where blue sky meets the pinkish salt. The mud will support you, just, so you walk out over it, briskly. The salt isn’t pure white, but is marbled with pinks and browns in places. It starts out cracked and crazed and fragile but soon turns diamond-hard, its little irregularities glistering in the brain-splitting glare. The causeway the Australian Army built to get Bluebird over the mud was washed away long ago in one of the lake’s occasional inundations, but by the shore the welded railway lines dragged over the salt to smooth it for Bluebird remain, as does part of the aerial that relayed radio signals from the middle of the lake. No trophy hunters here; even Trevor hasn’t been here for a couple of years, and the fact that so few people have set foot here since Campbell’s time makes you feel all the closer to the drama that played out on this stark stage half a century ago.

The first track – 15 miles long and 220ft wide – that had been graded flat at huge expense was ruined by the rain, and over the course of two British summers on the salt the Bluebird team had to grade a series of runs, each shorter and with less safety margin to the side to avoid patches of salt that weren’t drying, and the biggest of the salt ‘islands’ that the wind builds up on the surface. The delays caused frustration and incomprehension among Campbell’s backers, his staff and even Sir Stirling Moss, who questioned his organisational ability and his ability as a driver. Most of his major backers pulled out between ’63 and ’64 and his relationship with Lord Owen descended into lawsuits. Many couldn’t understand why he didn’t just go for it, and wondered if his crash at Bonneville had broken his nerve. ‘It’s this lake, this bloody lake,’ he said after pulling the car out of a 389mph skid over soft salt. ‘It’s out to get me and this morning it nearly succeeded. It scares me. It scares me stiff.’Campbell’s approach seldom eased matters. Evan Green, father of CAR’s Gavin Green and an Australian writer, TV presenter, rally driver and adventurer, was Campbell’s project manager. The two liked each other, but Green still described Campbell as ‘brave, fearful, stubborn, loyal, treacherous’, and ‘flawed, devious and covered in the warts of self-doubt’. But some fear and self-doubt are useful qualities in a record-breaker. Campbell, to quote Green again, had the ‘mind of a test pilot and the patience of a chess player’. He wasn’t interested in ‘trying and dying’, but knew he had to inch his way towards the record, every extra mile-per-hour a step into the unknown on that treacherous surface, the priority always to keep car and driver in one piece for the next step. As Campbell’s friend Graham Ferrett put it, ‘he wasn’t going to go out there and kill himself, if he could avoid it’.

Campbell suspended that caution for the 8.93 seconds it took him to pass through the measured mile for the second time to take the record. By now running out of time and money and running on a track just ten miles long – he originally had 15 – and with just 20 feet of safety margin on either side instead of a hundred, he had just four miles to accelerate Bluebird into the measured mile on the return, a mile less than on the first run. He hadn’t cut ruts in the track on the first run, but it was soon apparent that he was now. With the throttle wide open and the turbine turned up to 110% and 4400shp, Bluebird was tearing fist-sized chunks of rubber from its tyres and digging so deeply into the salt that it was tobboganning on its belly. Still Campbell kept his foot in, perhaps driven on by the vision of his domineering dead father that he later claimed to have seen in the raised glass canopy between runs. He exited the measured mile at over 430mph, still accelerating. Campbell’s two-way average was 403.1mph, the new Land Speed Record and the first time a wheel-driven car had ever broken 400mph.

On 31 December 1964 on Lake Dumbleyung in Western Australia he became, just, the only man to set world land and water speed records in the same year, travelling at 276mph in Bluebird K7. But they were hollow victories. By 1963 the 25-year-old Craig Breedlove had already recorded 407mph in his three-wheeled, jet-driven Spirit of America. The regulations at the time required a land-speed record car to be a car, and have four wheels and be wheel-driven. By the time Campbell set his new water record, the FIA had changed the land-speed rules, and granted the record to Art Arfons’ Green Monster, which had run at 434mph in October 1964.

But Campbell and Bluebird’s wheel-driven record stood until the next millennium. Campbell thought Lake Eyre’s surface cost him 40mph, and in perfect conditions Bluebird might have done 500mph, enough to take the current 458mph record back. I wonder if someone would like to try. Maybe the most extraordinary thing about this whole sorry, crazy tale is that amidst all the difficulties Campbell faced – human, financial, logistical and psychological – the world’s most advanced car simply didn’t figure. Bluebird ran uncomplainingly for two summers at hundreds of miles per hour over wet salt and in alternating fierce heat and monsoon rain. Campbell’s point about British engineering was proved, at least, and I have the same confidence and a twinge of nationalistic pride as I climb back into the Range Rover Sport and leave Lake Eyre with a long, long drag back to the world ahead of me, wholly confident that British engineering – great, once again – will get me home.