► 50 years of Porsche 911 motorsport

► We drive the 911 GT3 RS on the Monte stages

► An epic tale from CAR+

The rain’s stopped now, but the narrow road’s still glistening, its fractured surface triggering the Porsche’s ABS on bigger stops. Worse, the GT3 RS’s steering is telegraphing mixed messages; sometimes I can feel the huge tread blocks bite, sometimes they threaten to wash right over the weathered tarmac and rust-coloured pine needles – a little extra peril on an already heart-in-mouth drive. You don’t want to understeer on the Col de Turini: one mistake and there’s a fairly inconsequential knee-high wall between you, lots of fresh air and some spiky stuff far below.

So I hold back through the twistier sections, accelerating hard where the road opens, revs snarling past 8000rpm in second, punching to third, squeezing the brakes before the next bend, downshifting, mouth drying, hands fixed to the wheel like vertigo on a ladder.

The RS’s splitter scuffs the ground with a hi-hat ttissch through the fastest sections, gravel rattles around in the wide rear hips and the flat-six echoes off rock faces. All the while I’m hoping Herbert Linge and Peter Falk will be proud; that they’ll read how we followed the trail they blazed back in ’65.

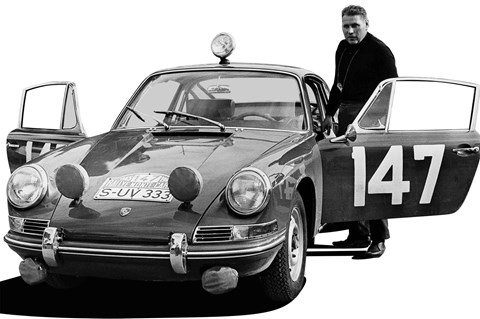

Fifty years ago, the 911 made its motorsport debut on the Monte Carlo Rally, just four months after entering production. In appalling winter conditions – 90% of the 237 starters recorded a DNF – the ruby-red 911, car number 147, battled to fifth overall and first in class.

‘Race director Huschke von Hanstein thought it’d be a great story if we could present the car to the world’s press in the Prince’s Court, Monte Carlo,’ recalls driver Herbert Linge. ‘He wanted the car to arrive undamaged; that was actually our fundamental duty, to bring the car safely to Monte Carlo.’

Perhaps even more remarkable is the fact that von Hanstein didn’t draft in rally experts: Linge and co-driver Falk were Porsche engineers. ‘I was working in the testing department and also as a race engineer, and I’d driven a few long-distance rallies: Liege-Rome-Liege, Tour de France, Corsica…’ says Linge. ‘So I’d already shown that I could drive, and Herr Falk also had some rally experience.’

The pair got two chances to recce the route – once in autumn ’64, once over Christmas – then off they went to beat the world’s best: Roger Clark, Paddy Hopkirk, Ove Andersson…

Typical for the time, 147’s mods were pretty basic: 2.0-litre six massaged from 128bhp to around 160bhp with Solex carbs swapped for Webers, polished intake ports, increased compression and a lightened flywheel; larger brakes, Boge shocks and a rear anti-roll bar were fitted; ZF locking diff and shorter final drive added; fuel tank upped from 16.4 to 22 gallons. A metal bar under the rear numberplate and two straps below the rear screen allowed the co-driver to stand over the rear bodywork like riding a husky sledge. If the 911 got stuck in snow, he’d help it claw extra traction.

Despite 147 being near production specification, the process of 911s being improved for and by motorsport had begun. And if you trace that process from then to now, you arrive at the 911 GT3 RS, the road car that homologates RSR racers.

Today, the bones of the car – rear engine, natural aspiration, rear-drive – remain, but at 493bhp the RS’s 3996cc engine has twice the capacity and three times the power of Linge and Falk’s car. In fact, the spec is a significant leap over even today’s 3.8-litre 911 GT3. Performance rises by a relatively small 24bhp and 15lb ft, and the seven-speed PDK gearbox is unaltered, but there are new rods, pistons, crank and cams; a 28mm wider turbo bodyshell; carbonfibre bonnet, boot and vented arches; polycarbonate side and rear windows; and 20-inch front and 21-inch rear alloys (the GT3 wears 20s all round).

Weight falls only 10kg, but factor in the wide body and bigger rear wheels and that’s a feat in itself. On track you might feel the extra downforce – a claimed 350kg at 186mph, double that of the last-gen RS 4.0 – but that won’t be so helpful through the Monte’s first-gear hairpins…

In 1965, the Monte competitors started from nine points throughout Europe – London, Frankfurt, Minsk, Warsaw, Lisbon, Monte Carlo, Paris, Athens and Stockholm – but covered equidistant mileages before ‘rallying’ at a common start, or parcours commun. A combination of public roads open to traffic and daunting against-the-clock special stages followed.

‘We started alongside 26 or 28 cars in Frankfurt,’ says Linge, ‘and only three arrived in Monte Carlo, the rest got stuck in the snow. These were the conditions from beginning to end.’

‘The car was just perfect for the conditions, with the rear engine configuration and the excellent traction on the rear axle,’ adds Falk. ‘Hanstein just wanted us to get the car to the finish, but since we were both motorsport drivers and excited, that order did not fit with us. We did not disregard it, but of course we didn’t want to be last!’

Our Porsche GB press car dictates a London departure, but at least I have a German – photographer Steffen Jahn – on notes for authenticity. He’ll be guiding me to Chambery, close to Lyon, 1965’s parcours commun.

A 2200-mile return sounds like flagellation in a race car with numberplates, but the GT3 RS’s suspension is surprisingly compliant – check the relatively chunky tyre sidewalls – as we head for Folkestone and the 918 Spyder-derived bucket seats all-day comfortable. Even the rear visibility is largely unhindered by both the criss-crossing cage and 747 rear wing.

Skirting over the open expanses of northern France, the weird but inherently correct logic at play in the RS hits home: we have a magnesium roof and fabric door pulls to save grammes, but also air-con, electric windows, electric height adjustment for the carbon-backed seats, and infotainment piling kilos back on. It’s a dichotomy that makes this hardcore machine easy to live with; delete it if you like, but I wouldn’t.

After an overnight stop and a morning on the autoroute we arrive in Chambery, poring over the map to find the twistiest, most indirect routes to Monte Carlo imaginable. Here Linge and Falk were allowed 30 minutes’ rest and a tyre swap; after 2001 miles, the really tough stuff was about to begin.

The first special stage lay between Chambery and Grenoble via the Col du Granier. Rauno Aaltonen drove against the Porsches in ’65, steering the Mini to victory two years later. ‘This was probably the most important stage,’ he remembers. ‘And the best: fast, winding, flowing.’

As we climb out of Chambery on the D912, the urban sprawl gives way to farmland, then forests, and Jahn folds the map with a ‘we won’t be needing this’ flourish when we spy thick black lines smeared over the tighter corners. The road climbs into the tree line, the cambered surface flicking over bridges and wrapping round hillsides. A scattering of hairpins link flowing full-throttle stretches.

Purple clouds hang heavily above but for now it’s dry, a chance to explore the GT3 RS’s dynamics. Other than driving off the road, you cannot accidentally unstick the RS in these conditions. The GT3 RS’s 325/30 ZR21 rear Michelin Pilot Sport Cup 2s are straight off the 918 supercar, and it feels like they’d sooner pull up the surface than relinquish traction.

I press the throttle hard, pulling back the delicate paddleshifters, up from second to third, sometimes fourth.The longer stroke – courtesy of a crank derived from the same-grade steel as the 919 Le Mans winner – means peak power is a little lower than the GT3’s 8500rpm at 8250rpm. But just like breaking traction, you have to concentrate hard to snag the limiter, instinct telling you to shift earlier. And the upside is extra torque; the RS feels more flexible, more urgent.

There’s comfort to be had in charging fast uphill, working against the gradient, knowing you’ll stop quickly if things go wrong. But the downhill sections on the D912 are at times terrifying: a lip of road and you’re eye-level with some big-tree torsos rooted tens of feet below. In the snow of ’65, in a car with a tendency to understeer on slippery surfaces? Most people would’ve crashed before the first stage; many did.

‘That Monte was the hardest in years,’ remembers Linge. ‘Visibility was down to 3ft in the snowstorms. The headline in Auto, Motor und Sport was: “The hardest thing ever!”’

In today’s conditions the RS’s front end just calmly follows my line, the alcantara-wrapped steering feeds back through my palms, suspension smothering undulations. Soon I start taking an aggressively early line into corners because I know the front will stick and I can have it all: fas-in, fast-out. It might sound unnuanced and detached, but it just promotes the most amazing feeling of connection, that everything you do is translated directly by the car without filter.

The D111 at Chamrousse leaps out from the map, a horseshoe laced with tightly knotted curls that appears cut from the topography for fun. It’s a seriously challenging stage, unlike anything I’ve driven on the Monte before; lush and green, wide and open, framed by huge trees, more Nürburgring than Monaco. As we approach, those heavy clouds dump rain like aerial firefighters.

In the rear-view, through the polycarbonate rear screen, plumes of spray kick up. Ahead of me the wipers work hard, headlights picking out streams of water. The aggressive Michelins might be optimised for the dry, but at least they make an attempt to cut through water these days. Stability control’s keeping busy, though; no unstickable rear now.

This is the kind of road where mistakes are compounded, especially on the long downhill plunges: you get your entry to one corner slightly wrong, get away with it, then find yourself out of sync for the next apex and, ultimately, out of road. In the wet, you need to invest in a run-out-of-talent reserve fund.

The next day we trace Linge and Falk’s tyre tracks south to Gap, cutting across the D900 to Digne Les Bains, then the N85 to Castellane, the stages at first expansive with ashen Alps towering surreally in the background like painted movie sets. The roads are almost empty, the scant traffic easily overtaken with the RS’s long lunges through the rev range.

It’s beyond Castellane that the Monte Carlo rally starts to take shape in your mind. We cut off the N85, latching onto the D2 towards the iconic Col de Vence. The road is tighter now, threading between rock faces and the little wooden barriers that guard the plunging gorges below. You need to be millimetre perfect at speed here, really leaning on the RS’s excellent £6k carbon-ceramic brakes and holding them on as you turn into corners, maximising front grip.

Somewhere up here Linge overcooked it, slamming the 911’s passenger side into a snowbank, Falk throwing the roadbook onto the back seat in protest. My German co-driver’s holding up well but we’ve got ideal conditions, and for the first time we can see the Med in the distance. We pull over, fold out the map on the large rear wing, just a whistle of wind cutting through the pines, then… what is that? The breathy mechanical thrum, the unmistakable wup-wup of two heel-and-toe down changes on the bounce; I spin on my heels, the ’60s 911 whizzes past us, brakes hard to a stop, slots reverse; no way!

The owner told his wife he was going for some milk, has been gone for hours and is unlikely to be back soon. We laugh comparing his 15-inch tyres to our 21s, and he says he prefers the oldies, that he almost feels safer because there’s only so much speed he can carry. Then he’s gone, that quest for dairy sounding increasingly urgent on a charge downhill.

We’re heading back further north now, destination Col de Turini, the climax of the rally in ’65. Not long before we arrive, thunder-cracks crash out like the earth’s tearing apart, then a chill wind heralds yet another deluge. As we climb up through the gorges, again there are the drops, the craggy rocks, the minimalist tumble protection, but this time it’s different: that frost-fractured surface, the even tighter confines.

The RS never finds a rhythm here, feeling a size too large for these undersized roads. But you do get the sense there’s a bit of old-school 911 magic to manage, the understeer if you’re ambitious with your slow-corner entry speed, the way you can accelerate early and the nose swings quite aggressively for the apex. And I love how everything seems to pivot around your knees; there’s a real energy to quick direction changes.

On the rare wider hairpins, I abandon the paddleshifters that twirl with the wheel and start to punch the changes on the lever, into the hairpins in first, initiating the slide early, then riding the revs and pulling for second with the back end twerking; the 911 goes all-consumingly feral, but it’s also unintimidating, balanced, communicative.

Linge and Falk had saved new studded tyres for the Col de Turini, but Porsche had also entered a 904 for the Monte and Eugen Bohringer and Rolf Wutherich were in second. Team orders dictated they got the new rubber, so car 147 was doing the Turini on used studs or nothing at all. ‘If we’d had more spiked tyres that would have helped us gain two or three places,’ estimates Linge. ‘The bald tyres were not so great.’

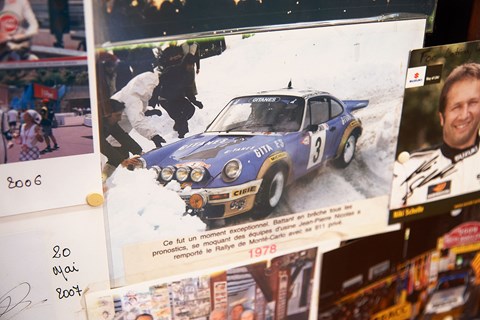

We take shelter at the 1607m-high stage summit, sipping coffee in the Hotel des Trois Vallees, looking at the signed pictures of rally stars, then skirt back down the D2566, through the narrow streets of Sospel, getting into a stride on the D2204 – wider, better sighted, more RS-friendly – as the Alpes Maritime tumble towards the coast. Over a thousand miles since we set out, now exhilarated and tingling with exhaustion, finally we’re looking out over Monaco, flat-six pulsing, the sickly stench of toasted brake pads carrying on the air.

In the terrible conditions 50 years ago, the nimble, front-drive Mini driven by Timo Makinen got here first. But it was still a publicity coup for Porsche: the 904 took second, Linge and Falk’s 911 fifth, photographed outside the royal palace as Prince Rainier and Grace Kelly looked on. It surprised the press, many at Porsche too.

‘There were certainly people at the company who were sceptical beforehand,’ says Linge. ‘They thought it reckless to enter with such an untested car, but after it went well everyone was happy that the 911 could perform so well right away.’

‘With a little more luck they could’ve finished higher,’ remembers rival Aaltonen. ‘The 911 understeered through slow corners, but the rear-mounted engine gave fantastic grip on the way out and the engine’s torque made it easy to drive compared with our high-revving Cooper S. The 911 also had 15-inch tyres compared to 10 inches on the Mini, a big advantage for the Porsche because it gave much longer tyre life.’

Soon after the celebrations, car 147 was sold without its engine to a dealer in Munich, then raced by French privateer Sylvain Garant before disappearing. Years later, rediscovered by a Monegasque Porsche specialist, it was sold to a German collector, and in June 2013 arrived at Porsche Classic. It was restored before the 50th anniversary of its most heroic feat.

147 is an incredibly important piece of motorsport history, a car that raised expectations ahead of Vic Elford’s first win for a 911 on the Monte in 1968. Bjorn Waldegard followed up in ’69 and ’70, and Jean-Pierre Nicolas was the last man to win the Monte in a 911 in ’78. Porsche hasn’t had a factory-supported world rally programme since Prodrive ran Henri Toivonen in a 911 SC RS in the ’80s. But when the FIA introduced the R-GT Cup for 2015, a route for the 911’s return to world rallying was opened up. So if you go to the Col de Turini or Sisteron you’ll hear that flat-six barking in anger again. Half a century after Linge and Falk’s incredible debut, the 911 is still doing the business in the mountains above Monte Carlo.

911: a rallying life

1965 Monte Carlo – Herbert Linge and Peter Falk finish fifth on the 911’s competition debut

1966 Gunther Klass becomes the European GT rally champion

1967 Sobieslaw Zasada wins Group 1 and Vic Elford Group 3 of the European Rally Championship

1967 Sobieslaw Zasada wins the Argentinian Grand Prix, a 2000-mile road-rally, in the only Porsche of 375 entries

1968 Vic Elford drives a 911T to overall victory in the Monte, breaking the Minis’ domination. Pauli Toivonen wins the European Rally Championship

1969 Bjorn Waldegard clinches the 911’s second Monte victory

1970 Waldegard does it again on the Monte

1978 Jean-Pierre Nicolas claims the 911’s last Monte Carlo win

1978 Vic Preston places second overall in the East African Safari, only losing the lead after striking a rock in the closing stages

1980 Jean-Luc Thérier takes victory in the Tour de Corse

1984 Porsche teams up with Prodrive, running Henri Toivonen and finishes second in the European Rally Championship

1984 Crewed by Rene Metge and Dominique Lemoyne, the 953 rally-raid 911 – forerunner to the 959 – takes victory in the Paris-Dakar

1986 The fiercely competitive team of Metge, Lemoyne and the 959 win the Paris-Dakar again

2014 Rally Germany: in the FIA R-GT Cup category Richard Tuthill gives a 911 its first WRC finish since 1984

The specs: Porsche 911 GT3 RS

Price: £131,296

Engine: 3996cc 24v flat-six, 493bhp @ 8250rpm, 340lb ft @ 6250rpm

Transmission: Seven-speed dual-clutch, rear-wheel drive

Performance: 3.3sec 0-62mph, 193mph, 22.2mpg, 296g/km CO2

Suspension: MacPherson strut front, multi-link rear

Weight: 1420kg

Length/width/height: 4545/1880/1291mm

Rating: *****

The specs: Porsche 911 (1965)

Price: £1990 (production car)

Engine: 1991cc 12v flat-six, 160bhp @ 6200rpm, 140lb ft @ 5000rpm (est)

Transmission: Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Performance: 7.5sec 0-62mph, 120mph

Suspension: MacPherson strut front, longitudinal torsion bars

Weight: 1050kg (est)

Length/width/height: 4163/1610/1321mm

Rating: ****