► 70 years on from the Battle of the Somme

► Phil Llewellin revisits the haunted fields

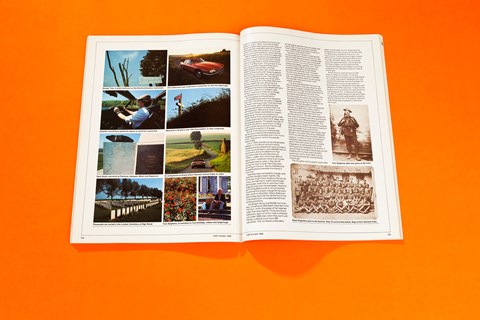

► Pilgrims Road taken from the CAR+ archives

Seventy years on from the bloodiest defeat in British military history, Phil Llewellin takes a Jaguar XJ-SC to Northern France, to haunted fields of the Somme

What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells,

Nor any voice of mourning save the choirs,

The shrill, demented choirs of wailing shells;

And bugles calling for them from sad shires.

Jaguar’s XJ-SC was the same blood-red as the poppies I picked in a field near the Oswestry birthplace of Wilfred Owen, the greatest of all war poets. I took them to the Somme region of northern France, to a hamlet called Thiepval, where more than 73,000 names are carved on the biggest of all British and Commonwealth war memorials. Those names commemorate only the men whose bodies were never found after history’s bloodiest battle. Thousands more, identified or mutilated beyond recognition, lie beneath neat headstones in cemeteries within a few miles of Thiepval.

The battle of the Somme started on July 1, 1916, after a week-long artillery bombardment that was heard in London, 200miles away. By November 17, Britain and the British Empire had suffered 420,000 casualties and General Sir Douglas Haig called a halt to what had been hopefully dubbed ‘The Big Push’. The Commander-in-Chief could then tell from his maps that the greatest advance had been along the main road from Albert to Bapaume. On that line, and on that line alone, the Germans had been pushed back just 6.5miles.

The poppies we took to France in the XJ-SC were for all who died on the Somme, for all who suffered there, and for all who came safe home. In particular, however, they commemorated the men of the 6th Battalion, King’s Shropshire Pals, friends and colleagues from all walks of life who answered Lord Kitchener’s call to arms and helped create history’s biggest volunteer army. In the words of one of the Great War’s more bitter songs, the 6th KSLI were part of Joe Soap’s Army whose ‘bold commander’ remained safely in the rear.

June was at its burnished best as we prepared to depart for northern France. I struggled with the cabriolet’s cumbersome roof panels, recalling the ‘easy for Leonardo’ line penned by Dylan Thomas after following instructions that made a model galleon look like a sea-going tramcar. Why didn’t jaguar go the whole hog with a genuine convertible? The XJ-SC attracts a lot of attention, but strikes me as an unsatisfactory compromise. You sacrifice two seats, plus boot space taken by the panels, without getting that real open-car feeling …

… But the engine is a massive masterpiece. In human terms, it combines the discreet efficiency of Jeeves with Rocky Marciano’s punch. The main drawback, of course, is a thirst worth of Brendan Behan. The 16.9mpg average included many miles of soft-pedal cruising on rural by-ways in France. At more typical speeds, brisk but certainly not breadneck, the astonishingly refined V12 did nearer 12mpg.

The power unit was appropriate, albeit in a roundabout way, because the world’s first tanks, which made their debut midway though the battle, had 105bhp Daimler engines. A theoretical top speed of 3.7mph in perfect conditions was reduced to 0.5mph over ground moonscaped by literally millions of overlapping shell craters. Temperatures inside the 28ton monsters reached 120degF. One officer went made, shooting engine to make it go faster.

Shropshire, Staffordshire, Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Berkshire, Middlesex, Surrey and Kent were all on the Jaguar’s route to Dover. They were just a few counties whose infantry regiments had been on the Somme in 1916, fighting alongside comrades from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and Ireland, and the doomed Deccan Horse from India, who charged High Wood’s machine guns with lances glinting in the July sun.

Driving through those counties on a summer evening, wafting along as quickly as World War One fighter plane, I could hear the ‘doomed youth’ of Wilfred Owen’s poem singing Tipperary and Pack Up Your Troubles as they headed for the Channel ports. The vast majority were not professional soldiers, although the battalions they formed became part of old established regiments. Butchers, bakers and candlestick makers, clerks, miners, farm labourers, estate agents and railway porters, they were typical of the 2.5million Brits who volunteered between August 7, 1914, and the end of the following year. Britain’s full-time army, just 247,432 men at the outbreak of war, had been decimated long before Haig and General Sir Henry Rawlinson launched the Somme offensive.

Harrison and I crossed to Calais early in the morning of June 30 … We followed the Autoroute for a few miles, then headed south-wards from St Omer. The Jaguar loped along quiet roads flanked by slender trees and small farms with few of the hideous modern buildings and now sully so many British landscapes. That sort of motoring is the Jaguar’s forte. Four inches longer than a Granada, it is no more a sports car than I am an Olympic sprinter. But a smooth ride, plenty of grip, and steering with rather more feel than expected combine with that magnificent engine to make the XJ-SC a superb tourer …

… What it lacks is an automatic whose kickdown is as responsive as the Porsche 928’s. Despite the engine’s prodigious torque, there was lag enough to make Graham Harrison’s monitoring of oncoming traffic welcome when we overtook trucks. His say-so gave me the extra second needed to telegraph the stokers for full power.

There were two good reasons for not asking the autoroute all the way to Bapaume. First, we had time on our side, and driving on French country roads is far more enjoyable than reeling in motorway miles. Second, this trip across what Will of Stratford called ‘the vasty fields of France’ gave me good reason to visit the battlefield of Agincourt. It was there that Henry V and the men of the long-bow, a small, hungry army ravaged by sickness and retreating to Calais, finally turned to face the French on October 25, 1415.

Ripe corn, rippled by a warm breeze, covered the fields where armoured knights, invariably and quite correctly described as the flower of French chivalry, charged to their death. Henry’s army, out-numbered by more than four to one, suffered only a few hundred casualties that day…

… Incidentally, the ‘V’ sign is from that period. Pre-battle formalities during the Hundred Years War included French heralds riding out to warn that captured archers could look forward to losing the first two fingers of the right hand. The bowmen, confident in their team’s record away from home, brandished those same digits and bellowed bucolic insults.

It is also worth mentioning that the heads of Henry’s yeomen were protected by leather helmets remarkably like those devised for tank crews on the Somme, half a millennium later. Unlike its medieval predecessor, the 1916 version had a chain-mail veil to provide a modest measure of protection for the eyes. Weapons worth of the Middle Ages were also used by troops fighting hand-to-hand in the trenches. They included clubs and daggers, and an elbow-length steel gauntlet with a built-in blade.

Harrison’s skill with one of Monsieur Michelin’s excellent maps unravelled another tangled skein of traffic-free minor roads as we made tracks for Doullens … I slotted my bittersweet Oh What A Lovely War tape into the cassette platter as the poppy-red Jaguar left Doullens and forward another rural by-way towards Albert, the only town on the Somme front. We could now see, away to our left, the low chalk escarpment backed by gently rolling down-land that the British assaulted on July 1, 1916. There, as at Agincourt, ripe corn was liquid gold in the sunlight. A skylark was singing when we paused at a deserted crossroads before taking a lane towards Thiepval.

No matter how hard I tried, it was difficult to picture this peaceful landscape being ripped apart by the bloody talons of war. Seventy years ago we would have been passing mile after mile of guns that between them fired 1.5million shells during that seven-day bombardment. But, as the Jaguar slowed to little more than the KSLI’s brisk marching pace, and as the tape played songs that made me swallow hard, I could picture endless columns of Tommies, joking and smoking as they marched to the trenches.

The Jaguar crossed the little River Ancre, which cuts through the escarpment, and climbed the short, steep hill to Thiepval, where Sir Edwin Lutyens’ huge memorial catches the eye for miles around. The poppies from Shropshire had reached their destination. I had expected to be deeply moved by the sight of all those names, but just shook my head and heaved a sigh. Thiepval is powerful enough to numb the emotions.

We spent a couple of hours seeking a room for the night, spurring the Jaguar along at an apparently effortless 90-110mph as it traced a rectangle bounded by Albert, Bapaume, Peronne and Ameins, where the Hotel de la Paix had a vacancy and was rated ‘quite comfortable’ by Michelin. I fretted a little, but Harrison was all smiles. ‘The light’s not good now,’ he soothed. ‘But later it will be perfect. Let’s go back to Albert and get something to eat.’

We were sitting outside a small café near the railway station, sipping cold beer and enjoying excellent omelettes, when we saw something that neither of us is likely to forget. Walking towards us from the station was a shortish man clutching two small suitcases and a plastic Boots carrier bag. Old, but not apparently old enough to have been in the Great War, he was asking the way to one of Albert’s few hotels. We drank up and offered him a lift.

His name was Tom Stephens, and he has boarded the train in Swindon at 6.30 that morning. We were wrong about his age. Tom was within days of his 91st birthday. The 21st had been spent in the trenches near La Boiselle, a five-minute drive from where we met him. ‘When we got there, the trench was full of Royal Fusiliers, all dead,’ he recalled. ‘Some of the lads said a machine gun had got them. I reckoned it was probably a shell. It didn’t really matter. They were dead.’

Tom later sent me a collection of precious photograph, sepia-tinted memories of himself kitted out for France, his future wife, and his comrades in a Royal Engineers’ field company attached to the Royal Warwickshire’s. There were more than 30 smiling men in one group. Fourteen came back from an attack launched in the third week of July, 1916.

We said farewell to our resolute and independent old pilgrim, because it was time to explore the battlefield. The light was ideal, and coaches crammed nine-to-five tourists were heading for their hotels as the XJ-SC purred out of Albert. Just before La Boiselle we crossed the front line held by the Rawlinson’s Fourth Army on July 1, 1916. The French Sixth Army had been deployed on both sides of the sluggishly meandering River Somme, while their allies attacked on a front that ran northwards for some 16miles.

We stopped on the crest of a ride near Pozieres, where Graham photographed the Tank Corps memorial while I looked back towards Albert, contemplating the start of The Big Push. The success of the plan adopted by Haig and Rawlinson depended on the artillery. As they assembled in the trenches, most men of Joe Soap’s Army found it easy to believe that nothing, not even rats, could survive the bombardment’s fury. The infantry assault, they were told, would be like a stroll in the park on a Sunday afternoon. All they had to do was advance at a steady pace and occupy trenches that would be manned only by dead Germans. Rawlinson, safe in his chateau near Amiens, was convinced that a charge would reduce his men to a rabble.

But the great bombardment’s prolonged ferocity was more apparent than real. The British actually mustered far fewer heavy guns per mile than their French allies, and had relatively few experienced officers to direct their fire with precision. About one shell in here was a dud. Others exploded on impact, sending up impressive eruptions of rubble rather than penetrating the chalk and devastating the Germans’ deep, well-equipped dugouts. The great strength of those fortifications was known to Haig and his staff, because the French had captured one earlier in the year.

As the Tommies soon discovered, lighter guns had failed to destroy the tangled acres of barbed wire in no man’s land – the wire on which thousands were to die.

July 1, 1916, stands out as the greatest disaster in the British Army’s history. Awed by the bombardment and confident in their commanders, some 60,000 men of Kitchener’s Army flooded from their trenches when the whistles blew at 7.30am. Laden with more than 6olb of equipment – relatively more than mules were expected to carry – they set off across no man’s land, their bayonets twinkling in the sun. Some cheered and kicked footballs towards the enemy’s front line.

Had they been allowed to charge, and had their burdens been lighter, the Tommies might have stood a chance. As it was, the Germans, watching through periscopes, had time to race from their dugouts and man the parapets. Machine guns firing 600 rounds a minute started traversing the slopes, slaughtering wave after wave of attackers. Many died even before they reached the British front line, hit by shells from unsuspected German artillery positions.

Joe Soap’s Army lost 60,000 men that day, including 21,000 dead. Most fell in the first hour, when the gates of hell opened wider than ever before. Thirty two brave battalions, each of which had numbered just under 1000 men when they went over the top, suffered more than 500 casualties. The 1st Newfoundlanders, whose preserved trenches we visited, lost nearly 700, including all their officers. Their tragedy was matched, almost to a man, by the 10th West Yorks.

Harrison and I moved on, saying little as we pondered the enormity of it all. We went to High Wood, where clustered trees were like a dark, menacing cloud posed on the northern rim of a shallow, tranquil valley waist-deep in golden corn. Two months of grim fighting reduced the wood to a desolation of splintered stumps and cratered mud …

… The land was deserted that evening. We remarked on a solitary dog’s single bark as the Jaguar whispered us across the valley from High Wood to Bazentin-le-Grand, an impressive name for what proved to be a few farm buildings on the reverse slope of a south-facing ridge. In the early hours of July 13, 1916, it was attacked by a force that included the 7th Battalion, King’s Shropshire Light Infantry. The Battalion had numbered 33 officers and 905 other ranks when it reached the Somme a few days before.

Several were killed when their own artillery fell short. The rest were faced with two rows of ‘exceptionally strong and quite uncut wire’ up to 20 yards deep in places. None of the first wave got through. The German machine gunners had the easiest of targets when following waves closed on their comrades. Survivors of that typically doomed assault eventually took refuge in a sunken lane about 200yards from the trenches they had been sent to capture. In a few minutes, the battalion had been reduced to six officers and about 135 other ranks.

The slaughter continued for week after week, month after month. Rats became bloated to the size of cats as they feasted on dead men roasted by the sun in no man’s land. The buzzing of huge, corpse-fed flies could often be heard above the thunder of battle. When they occupied trenches opposite Serre, one of several fortified villages, the Shropshire Pals found themselves waist-deep in stinking cadavers that had been there for nearly a fortnight.

When the sun had set we hurried back to Albert for a beer. In the bar, surrounded by members of his battlefield tour party, was Martin Middlebrook, the Lincolnshire farmer who First Day on The Somme is a stunning narrative distilled from hundreds of interviews with veterans of 1916’s disaster. I hope he will forgive me for quoting a Private Smith of Joe Soap’s Army: ‘It was pure bloody murder. Douglas Haig should have been hung, drawn and quartered for what he did on the Somme. The cream of British manhood was shattered in less than six hours.’