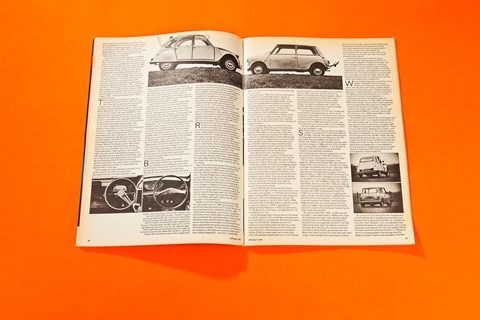

► Survival power: our cover story from April 1978

► Iconic road test, as Mini meets Citroen 2CV

► An archive gem from the CAR back catalogue

How should one define the age of a car?

Should it start with the concept or the realisation? It could be calculated from the day when a twinkle in the inventor’s eye evolves into the first tentative lines on the back of an old envelope or menu card, but cars don’t emerge from the factory doors just nine months later. The incubation period is quite unpredictable — it may be stretched for years by commercial problems or social upheavals so perhaps we should date a model from the time when the public can buy it.

For the origins of Citroen’s 2CV you have to go back to the turbulent France of the 1930s, economically depressed, socially eruptive and politically unstable. Within the decade preceding World War Il the French motor industry in terms of independent makes was… decimated, although the three larger mass producers — Citroen, Peugeot and Renault in that order —all survived. But only a year or so after the introduction of his first revolutionary 7CV Traction Avant (the front-drive Light Twelve in the UK), André Citroen was in financial tatters and had to sell out to Michelin. It was in 1936 under Michelin patronage that Pierre Boulanger conceived his mechanical umbrella, alias, to the less indulgent, his motorised dustbin. More basic than the Model T Ford, it was likewise intended to bring motoring to those who hitherto had been unable to afford a car. In a book published in 1958 Jean-Pierre Peugeot captioned a photograph of a 2CV: ‘Il y a cinquante ans, 95 percent de la population n’avait jamais vu la mer.’

There were said to have been 250 production prototypes made in time for the Paris icon of 1939, still-born because of Hitler. All except one of these were deliberately destroyed, and the 2CV’s first presentation before a stupefied public was not until the Salon of October 1948. Some parallels with the VW story are self-evident, for that car’s concept goes back to 1934 or earlier and by the late ’30s Hitler’s Master Race had begun paying instalments for the people’s car they would never get. It too reappeared in the late 1940s when the war was over.

The Mini’s back story

In contrast, not a moment was lost in bringing the Mini to fruition. Early in 1956 Alec Issigonis, after a spell with Alvis, was persuaded by Leonard Lord to move to Longbridge with the specific task of hatching and developing new projects for BMC. In September that year Egypt’s President Nasser created a fuel crisis by closing the Suez Canal, thereby generating a highly contagious rash of bubble cars. Lord’s attitude was that if the fuel starvation was to continue BMC had to meet this competition head-on – and they would do so on their own terms with a properly engineered miniature. After all it had been his predecessor, Herbert Austin and his Seven in 1922 – a real car in miniature – that had terminated the post-World War I epidemic of crude cycle-cars. By July 1958, a well-tested prototype Mini was ready for Lord’s trial and approval and it went on sale at the end of August 1959 – initially as the Morris Mini-Minor and Austin Seven.

The 2CV has been marketed for close on a decade longer than the Mini, and the current word filtering through the tottering Leyland conglomerate is that the ‘old’ Mini has been reprieved under the Edwards regime, rather than being replaced by that most heavily publicised non-event of recent years, the new AD088 Mini. But what then are its prospects of survival for another 10 years? And might the 2CV still be in production, broadly in its present form, a decade hence? Both being predominantly home-market cars which could not be sustained by their export outlets, their futures have to depend on social and political stability in their native lands and on their progressive evolution or adaptation to meet changing conditions. To go on being wanted they need to be reasonably up-to-date in behaviour and amenities without surrendering individual characteristics to transient fashion. Here the Citroen must have the advantage because it has no direct rivals other than the basic Renault 4 whereas counter-Minis keep sprouting in Europe and the Far East. Moreover, where cars are concerned, the French, for all their impeccable taste in other spheres, seem either highly resistant to the most barbarous assaults on their aesthetic sanity or actually to relish them – you don’t have to limit your observations to the 2CV to be convinced about that. For them almost any ugliness or eccentricity in sheet metal is tolerable so long as it adds to practicality, or at least does not detract from it in any way.

Mini vs Citroen 2CV

At this stage we might look back to the 2CV in its youth’, trace some of the more significant developments over the years, see how it rates today in current company and then look back to original Mini compared with its modern counterpart, but always bearing in mind that the Citroen and the Mini are no more alike than French chalk and English cheese, and that the continued success or otherwise of one is unlikely to have much effect on the other from a sales point of view.

Over the years visitors to the Paris Salon have been diverted by numerous machines that fell nothing short of playful bizarreries, even if their inventors fully intended them to be taken seriously. No one had expected such a device to emanate from the Quai de Javel, however, and the poor little 2CV left the Press momentarily speechless with incredulity before receiving a verbal avalanche which included some pretty uncomplimentary nicknames. True, it looked somewhat gawky among the flashy new creations in the Grand Palais from the drooping corrugated nose to the canvas hump covering its tubular framed body. The four doors, hung from the centre pillars on biscuit tin hinges, could be lifted off in a few seconds while wings and the bonnet could also be detached quickly for repair or replacement. Inside, there was room for four adults on lightly padded canvas hammocks slung by rubber bands from tubular steel frames. Crude to look at but much more comfortable to sit on than most of the fancier garbage in other low-priced conveyances. The top could be rolled back to let in the sun and wind, and the seats were easily removed for le piquenique or to aid transformation into a beast of burden.

But you had to look under the skin for reassurance that this was no flippant folly – but a deadly serious design by one of the most forward-thinking and inventive constructors, a light and spindly looking piece of machinery intended for hard work and rough treatment with minimal maintenance, and with a ground clearance and super-resilient springing that enabled it to traverse appalling territory without breaking itself or the occupants. The base was a boxed platform frame with leading arm front and trailing arm rear independent suspension, the pair on each side sharing a common coil spring enclosed in a horizontal cylinder under the platform and compressed by tension rods attached to the suspension arms. Front and rear suspensions were thus interconnected; you might call it fully interdependent suspension. The arm movements were countered by an inertia damper at each wheel loosely consisting of a weighted piston moving up and down between springs in a closed cylinder. In addition, there were adjustable disc-type friction dampers contained in the front arms.

‘Your average Frenchman couldn’t burst it even by snorting down the M1 full-chat for hours’

Right from the start the engine has been a horizontally opposed air-cooled flat twin, with aluminium heads, dry-linered aluminium cylinder barrels and pushrod-operated overhead valves in hemispherical combustion chambers: an inherently efficient installation but so restricted by the intake arrangements that your average Frenchman couldn’t burst it even by snorting down the M1 full-chat for hours. It had an oil cooler, and electric self-starter (the first prototypes were lashed into action by a whipcord), headlamps that could be adjusted for tilt from the driving seat, an all-synchromesh four-speed transmission driving the front wheels, Lockheed hydraulic brakes (the front drums being inboard), and screen-wipers propelled through a dog-clutch by the speedometer cable – the slower you went the fewer wipes you got, and vice versa.

About the only French quote I know without LJKS to prompt me was aptly penned by Alphonse Karr, although he died (in 1890) when there were precious few automobiles around, let alone any cars: Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose. The more things change, the more they are the same. By that reckoning the 2CV must now be more the same than it ever was because there have been a lot of changes in 50 years to increase performance and improve road manners without deranging its character or losing sight of its original purpose. The engine capacity has expanded from 375 to 602cc and the power output has more than tripled since the initial 9bhp, although a 435cc version is still available in the showrooms.

Maybe it is still not appreciated-universally that the ugly sisters Ami (b. 1960) and Dyane (b. 1967) are almost identical with the 2CV under the skin, like dressing Superman in different uniforms. Major modifications to engine, transmission, suspension and brakes have usually been incorporated in the Ami and Dyane first, but today there’s precious little difference now the 2CV has the bigger engine option and those remarkable inertia dampers have been replaced by horizontal dampers of the hydraulic variety. The 2CV doesn’t yet have front disc brakes, or the high compression engine with twin-choke carburettor – but then it’s easily the lightest of the trio so the performance disadvantage is insignificant.

During the early 1950s the motoring landscape of M.Bibendum’s native land looked in danger of becoming overwhelmed by these strange little mechanical mules with corrugated noses, usually laden with complete families and most of their worldly possessions. It was almost as though this new proliferation of everyman transport were touching off some latent migratory instinct. Mixing a few metaphors, the first 9bhp cars made an extraordinary sort of roller – progress along France’s typically undulating routes, puttering up each long incline at a mule’s pace then careering down the other side with all the reckless abandon of a gasoline swine.

Gross under-power was countered by excess braking capacity, the antithesis of the celebrated Ettore Bugatti cliche. M. Boulanger might have boasted: We make our cars to stop, not go. But there was nothing cut-price about the machinery under the tin shed body because Pierre Boulanger knew full well his compatriots would soon discard anything that could not be hammered flat-out all day. And 2CV customers would include a large proportion of peasant farmers and the like who would never get around to reading what it said in the handbook about routine maintenance.

Although the Ami was intended as a supplementary model, I suspect the Dyane was planned as an eventual 2CV replacement, having such a similar specification right through to the folding roof. It has most things a little or a lot better – especially visibility, ventilation and baggage space (the spare wheel being under-the bonnet)-but by 1967 the original was firmly rooted in the French scene, as much a part of many households as the bicycle had been, and its form was established and accepted – warts and all. And, would you believe, the 2CV had become so tarted up and refined with little improvements that a few years ago the company reintroduced a back-to-basics utility version for the home market.

The UK’s relationship with the 2CV

During 1954-59 right hand drive 2CVs were assembled at Slough, and then cost quite a bit more than even a de luxe Mini. In 1974 the French factory began making a RHD version, which now undercuts every car on the UK market except the Fiat 126. Production figures for the 2CV from 1972 to 1976 have remained remarkably stable except for a jump for obvious reasons in 1974. It represented 24.8 percent of production in 1 972, 23.2 percent in ’73, 30.8 percent in 74, back to 22.9 percent for 75 and 23 percent in ’76.

Pierre Boulanger died in an accident at the wheel of a DS19, another of his unorthodox masterpieces, quite soon after its introduction. By how many years might his little 40mph umbrella outlive him? Impervious to changing fads and fashions, it has been favoured directly by the world oil crisis and rising fuel costs, indirectly because the present 70mph 2CV6 can keep station with most other traffic restrained by speed restrictions. Still without direct competition as the cheapest car you can buy with four doors and true riding comfort for four adults, it also boasts the meanest appetite. While demand is sustained there would be no logic in discarding a vehicle with a unique and socially accepted character to replace it with a newer design, inevitably more expensive. Could it last another decade? If you believe in plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose, why not? It cannot be boasted of the 2CV that it introduced a new prefix to everyday parlance, that its social acceptance transcends all class distinctions, that its record of outright and class wins and team awards in national and international rallying and circuit racing during the 1960s was second to none, that more than two million were made in its first decade … but the trouble with laurels is if you sit on them too long they begin to sag.

Sir Alec Issigonis will tell you that no thought of a career in competition influenced the AD015 concept, although really good roadholding and handling were certainly prime objectives. But five years after the original 848cc car went on the market with 34bhp, the type reached its power peak (as a retail product) in 1964 with the 1275cc Cooper- Mini S, giving 75bhp at 5800rpm. From October of that year all Minis except the long-wheelbase Travellers had Hydrolastic displacers interconnecting front and rear suspensions, hailed by Laurence Pomeroy (in The Mini Story) as ‘a matter of major consequence in small car design’.

On the cover of the latest catalogue is the greeting: Welcome to the best Mini yet! How so? Today no Mini has Hydrolastic, although some who have been connected with the car’s sale since 1959 consider it to have been the most successful application of the Hydrolastic principle. The most powerful Mini in 1978 is the 1275GT which has-only 54bhp. In 1959 the Mini catalogue claimed 34bhp for the 848cc car, and today the figure has dropped 5 percent to 33. The old 998cc Cooper-Mini used to give 55bhp, but the current Mini 1000 with 39bhp is only fractionally better off than the long defunct 998 Wolseley and Riley versions (38bhp). The 850, costing now £1990 compared with the 2CV at £1647, has no face-level vents or hinged quarter-lights, a single instrument dial for speedometer and fuel level, no front door pockets – and only the Clubman has disc front brakes. There have been hidden economies, too, like the deletion of the ingenious rubber rings clamped to the camshaft sprocket to assist in tensioning and quietening the chain driven mechanicals.

Driving the latest Mini 1 000 – an 850 was not available-I was taken back to 1959 by-the-jumpy ride. Nineteen years ago it seemed pretty good compared with contemporary rivals especially because none could approach the Mini’s roll-free stability and sheer lightning mobility in terms of handling. Now constitution’s like mine are more sensitive to being shaken up and there are neo-Minis from other sources that treat me much more kindly. It was wonderful to come back to a front-drive car with such light, sensitive steering although the directional stability seemed reduced. Radial tyres have reduced road noise, but a great deal of commotion comes from under the bonnet, accentuated when you open the face-level vents. For motorway cruising the radio was a lost asset, drowned out by the din.

I missed the elbow-room under the sliding windows, the huge rigid door pockets that could carry a week’s supply of milk bottles. Besides, one used to be able slide the windows for ventilation without all the noise and draught today’s winding ones promote. I couldn’t find a mid-position for the heater knob to provide a setting between stone cold and stuffy heat. The little driving seat cushions have too much pressure under the thighs, the rear seat backrests have practically no padding at all, and the 1000 engine seems very unresponsive.

The appeal of basic cars

Why will people today pay so much for such a Spartan, outdated product? Are they impervious to the awful ride and Noddy seats? Are they won over by the cosmetic details pointed out in the showrooms? Probably they buy it because it’s what they know, a familiar companion for 19years, once the pride and joy of our motor industry with its world-wide reputation in competition and with a consequent wide and enthusiastic following in Europe. BMC, followed by BMH and finally BL, have so often failed to develop and fully exploit their best products to keep them attractive and abreast of changing times. For instance, the Issigonis Morris Minor (which might have enjoyed the Beetle’s success), Austin A40 (Pininfarina version), MGB, Austin/Morris 1800, Austin-Healeys large and small. .

Should they have made the Mini a hatchback with New Look styling? If so, Innocenti showed how to do it several years ago. Or should it stay just as it was with only detail modifications (as today’s 850 and 1000) and a possible hatchback addition? There is much to be said for keeping such a classic, with its simple functional form, in the original image as VW did with the Beetle; but just to maintain station with the opposition? No, the Mini needs refining and quietening mechanically, and a more resilient suspension which surely could be achieved more cheaply with steel springs. Even cleverer use of space within the body shell is now needed to provide a better driving position and a more adult design of seating and this would call for some rearrangement under the bonnet.

Of course, this isn’t telling the new management something they don’t already know and they must be aware that a reprieve for the Mini as it stands is a very short-term salvation. This is an old bottle that would be the better for some new wine. and it could be given a new lease of life if this can happen before the cash customers lose their taste for it. Without it, the sort of staying power that has kept the 2CV afloat just doesn’t seem to be available in the Mini.