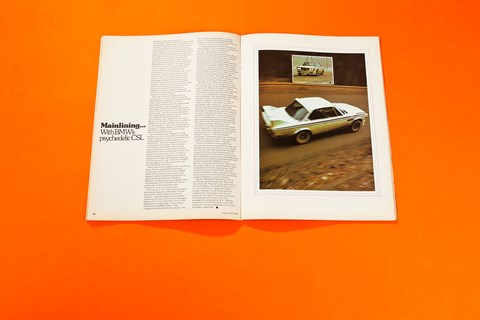

► Mel Nichols drives the BMW 3.0 CSL, March 1975

► Mission: deliver the CSL to Munich in one piece

► A classic road trip from the CAR magazine archives

The task was simple: deliver a BMW 3.0 CSL to Munch. The point, however, was a little more esoteric. The days of cars so ostentatiously aggressive, so patently spawned by the world of motor racing, so downright phallic as this winged monster CSL are over and gone. Were such machines worth the bother? Could they take two or three people across Europe any faster, more safely or any better than a less pretentious or less performance-orientated coupe or saloon? Would a standard BMW CS do the job just as satisfactorily? Moreover, do the speed limits now blanketing Europe render the coup de grace, once and for all, to such high performance cars? And do they consume expensive continental petrol at such a rate that they’re a liability rather than an asset even if you do ignore the police?

We left London on a Wednesday, threading through the cold, drizzling dreariness of the pre-dawn in order to make the first ferry out of Dover. Eighty-odd miles around London a day or two before had sucked the top from the fuel supply, but no longer did we bother to top up before ca-clonking onto the ferry. A quick check had shown that the 74p gallon had made British fuel the most expensive in Europe, apart from Italy’s 90p rip-off. Better to fill up in Belgium, even France or Germany. Could you have expected that a year ago?

The French coast brought sunshine, the markings of a magnificent winter’s day, and striking out from Dunkerque to the new autoroute that slices south of Lille and Brussels to Aachen we began to settle, easily, into the rhythm we wanted. There wasn’t much traffic, but the slow and steady pace at which everyone was travelling was certain testimony to the efficiency of the enforcement agents. Take a risk? Open the BMW right up and hope to spot the traps or the pursuers? No; play it cool and ignore the car’s potential, no matter how much it cried out to be used. Better to benefit from its abilities at a slow, almost dream-like 70mph and savour the day, not the law.

Indeed, our caution paid dividends. Not long after crossing Belgium an Opel Commodore GSE flashed past. Behind him came the police, and when we saw the two parties beside the road a little further on, the gendarme’s stony face showed no mercy. Only later did we learn that the instant fine for exceeding the speed limit in Belgium is now 10,000 francs for starters, with an extra 1000 on top of that for each kilometre one logs above the limit.

The CSL had been resident in Britain as part of BMW Concessionaires’ test fleet. By rights, it should have been sold off months ago – it had logged a high mileage and it no longer fits the image BMW want to portray here: racing is dead; compact luxury is in – but somehow it had evaded the hammer. Simply being in Britain, the CSL also evaded losing its trio of spoilers. They’re outlawed in Germany; BMW supply them in the boot of each CSL and it’s up to the owner if he wants to defy the police and fit them. Not only the police: during the height of the fuel crisis in Germany, to drive something which looked as if it might guzzle fuel brought unsavoury reactions from other motorists. There wasn’t much lure to fit the spoilers – unless, of course, you considered them essential to the CSL’s performance. But more of that later.

The CSL was and is the fastest BMW road car. It is based on the CSi coupe, but the familiar six-cylinder engine is bored an extra 4mm and stroked very slightly to increase the capacity from 2985cc to 3153cc in line with homologation requirements for the 430bhp racing coupe (Ford produced the Capri RS3100 with a similar capacity or precisely the same reason). Compression is untouched at 9.5 and so is the electronically-controlled Bosch fuel injection, but the power goes up from 200 to 206 (DIN) bhp at 5600rpm and there is a more than worthwhile increase in torque (developed at slightly lower revs). The transmission and final drive ratios are as for the CSi, but the CSL is armed with a limited-slip differential.

There are suspension differences: the body is dropped 0.8in to lower the centre of gravity, an extra degree of negative camber has been cranked on to the front wheels to improve stability and handling, the coil springs were replaced by stronger, more progressive ones and Bilstein gas pressure shock absorbers took over from the standard dampers. This new spring/damper combination allowed the front and rear stabiliser bars to be flung away. Fat 7in alloy wheels carrying the excellent Michelin 195/70 VR14 XWX radials replace the normal 6in rims and lower specification tyres and the steering was uprated to the ZF-Gemmer worm and roller system (but with a slightly slower ratio than standard).

Part and parcel of the CSL is a ligtweighting job in which alloy door skins and bonnet are substituted for the steel ones, the front bumper is replaced by a black plastic imitation bumper and the windscreen is made from special Verbel laminated glass. The chin spoiler and the small one at the lip of the boot lid, along with the black rubber air guides on top of the front mudguards, are part of the basic CSL package.

The extra, outlandish spoilers – the deflector that runs across the rear of the roof and the wing that rises up from the boot – are supplied with the car so that, BMW say, the man who wants to go racing full time can bolt them on or the part-time racer can put them on for his weekend sport and take them off again to run around the streets, so appeasing the police.

Apart from running the risk of being booked in Germany, what happens when the spoilers, developed for the European Touring Car Championship racer, are used? Drag is reduced by 16 percent, improving penetration as greatly as if the car had an extra 50bhp, BMW say. Fuel consumption is improved, straightline and cornering stability is improved, and so is crosswind resistance.

The Bosch injection makes the CSL fire up immediately and idle easily. Even in the cold at 5am there is no hesitation as the clutch comes out and the 2567lb coupe (that’s 562lb down on the CSi) moves away. Smooth. Fuss-free. No trace of meanness, no hint of high-level tuning. Now, running along this motorway towards the German border, the thing is turning over as sweetly as ever and you’re settled back comfortably in the special rally-type bucket seat. There’s no squab adjustment, but the arrangement is as close to perfect as most drivers would want it: distances to the wheel, pedals and gearlever are precisely correct, vision is excellent, instruments and controls located for easy reading and reaching. The leather-covered, drilled-spoke wheel is mounted high, in an old-fashioned sort of way. But it is comfortable and, when the time comes, will permit appropriately deft applications of opposite lock …

Meanwhile, the fuel tank reads dangerously low and there’s been no hint of motorway service area. Playing safe, we swing off into a pleasantly sleepy town called Tournai, swap Deutsche marks for Belgian francs and fill the CSL. Calculations show the figure has been a surprising 22mpg, including the running around London. For the most part, we’ve been touring at 75mph, maybe 80 when the chances of being caught look remote. The next tank, taking near Frankfurt, confirms the figure – 22.2mpg this time, and we’ve been travelling at 90mph since we’ve been in Germany where the 80mph limit is advisory only, occasionally logging 100mph or more. There is no doubt, then, that the aerodynamic aids fulfil this part of their promise. You will not see such figures in a CSi or an ordinary CS. No way.

The boarder guards, as we’d passed into Germany, eyed us with quizzical friendliness. The fins might have been illegal, but they still made the car look dramatic and exciting, made our journey purposeful, and we were given the distinct impression that it was good luck to the mad Englishmen for disregarding the whole fins affair. Bolting back out onto the E5 autobahn, winding the CSL right out in first and second to slip into the traffic flow and listening to the well-mannered rumble from the OHC six and watching the tachometer needle reach to its 6400rpm red line (where it provides 38mph in first, 65 in second and precisely 100mph in third), revealed an aspect of the CSL I hadn’t explored in depth before: the acceleration. It isn’t earthshattering, for this is not one of the big-stick supercars. It is still, however, thoroughly fast, getting to 60mph in 7secs and pushing driver and passengers deeply into the seats as the bonnet lifts and the growl from beneath it deepens. The car has its fair share of the mailed first/velvet glove ingredient and when asked, it responds. Most of all, it feels especially well balanced: engine to chassis to brakes.

Although the German speed limit is advisory only, it’s quite obvious from the steady 85mph progress of almost everybody that it doesn’t pay to take too much advantage of the situation. Roadside radar, prowling patrol cars and predatory helicopters complete the message. So we stick to 90mph, a speed we consider will be safe enough, and the cruising is pleasant; the slightly greater speed than we’d dared used in Belgium sharpens up driver concentration, and, indeed, the car. Up to 90mph, the CSL feels pretty much as any big BMW does: supple, smooth, fairly precise but not notably so. Above 90, things begin to change and above 100mph you really know about those spoilers. From then on you almost praise them aloud.

As the speedo nears 100mph, the CSL tightens up, much as the professional athlete might suddenly turn on for a race rather than simply jogging around the park on his morning run. The steering goes rock solid, pinsharp (but not heavy). The ride stays comfortable, but seems to firm and any trace of softness is hurled away. You can really feel the thing sitting down on the road, everything clicking into place. It’s one of those very special ‘fingertips and seat-of-the-pants’ feelings that make real motoring in a fine car such a high. You feel confident, but not aggressive; safe, but not shut off from the reality of the road.

And so the miles disappear with increasing ease. The top speed potential remains unexplored, save for one burst to 130mph where the rock steadiness is even more apparent. But the benefit of having such a speed and power reserve (100mph is 4500rpm, just about the torque peak) is that a quick prod on the throttle thrusts the car past trucks on the narrow two-lane autobahns, and out of harm’s way.

All three of us – for I had two passengers, both travelling quite comfortably: the thin backs of the rally buckets improve rear legroom – were developing considerable respect for the CSL as the sun at last began dipping. Don’t misunderstand: the car had started with no advantage. I have always disliked the big BMW coupes. They disappoint me after the 3-litre saloons. The CS isn’t just a coupe version of the 3.0-litre saloon: it’s based on the decrepit 2000 chassis. Careful development, however, as in the CSL, can cure no end of ills.

A map showed a side road leading from the autobahn down to a series of villages on the River Main, about 40 miles past Frankfurt. We selected correctly; Marktheidenfeld, where we stopped, was a quaint and quiet little wine town on the river bank, full of very old houses, wine cellars and poky little streets as well as an enjoyable hotel called the Anke where the landlady was good enough to direct us to a restaurant called Main Blick – River View. Indeed, it looked out onto the river and the moored barges and the food was as excellent as we’d been led to believe. What’s more, the bill totalled £2.30 each! The hotel was £3 a head, so don’t think you can’t travel cheaply in Germany if you stay off the main routes.

We were within 200 miles of Munich by now and our plan for Thursday was to drive through the mountains into Bavaria seeking locations for Mervyn Franklyn’s camera. Again, the weather was clear and bright after a night that brought very thick frost. The CSL, on the soaking and slippery back roads, was surefooted. One did not feel inhibited by its power. When we reached the high country, however, we drove into mist, icy roads and snow. I hate black ice, and I proceeded very cautiously, using only third and top. But after several miles, it was obvious that the CSL had an extraordinarily high level of roadholding, and the handling to match if the grip did break. Soon, even in those foul conditions, I was driving the car full out, snuggling back in my rally bucket, getting absolutely precise responses from the engine to the movements of the throttle and lapping up the smoothness and fluidness of the steering. We found a bend for photographs, a tight and constant uphill curve, thoroughly soaring. After a couple of exploratory runs, it was being taken at 60mph in second – that’s full power, remember – and there was no hint of the tail snapping more than a few inches out of line. That bend sealed my faith in the CSL.

It was all downhill running after that: literally, because we crossed the range and figuratively, because I felt so much at ease with the car that it was pure and unbridled enjoyment without any considerations of needing to spare further time for familiarity. We completed our journey by streaking along the pleasing and almost deserted roads that snake through the hopfields close to Munich, and switched off at our hotel in the city at 6pm. We could, had we wished, have completed the trip the night before if we’d pressed on down the autobahn. But that would have been to deny ourselves a day of motoring far more excellent than anyone has a right to deserve in such conditions.

The CSL was worth the both; the fins and wings may be passé now; they have done their job. They did it very well and it is not hard to feel sorry that their day is done. Is a car of the CSL’s capabilities done though? No way. To eat up the miles so competently, to be given such driving pleasure even when sticking fairly closely to the speed limits and to do it at an average fuel consumption of 21.166mpg (better than a 3-litre Granada could have returned in the circumstances) is more than desirable, even now.