► An archive gem from CAR magazine

► Back when we profiled Lewis Hamilton

► It’s 2002 and he’s entering Formula Renault

As Lewis Hamilton scores his extraordinary seventh F1 world championship in 2020’s pandemic-stricken winter of discontent, we leaf through our near 60-year back catalogue to pick out an early interview with the motorsport ace. It’s a damp bank holiday morning at Brands Hatch in 2002 and CAR’s go-to motorsport reporter Jeremy Hart is spending the day with Hamilton and his family to uncover the steely potential of this precocious talent. Read on for the full interview.

The full CAR magazine interview with the young Lewis Hamilton, July 2002

Defining moments in sporting history normally come wrapped with the pomp of a coronation, the aural barrage of a boy band gig and the chest-thumping excitement of gladiatorial combat. They don’t normally come cloaked in a damp spring mist soon after a battleship grey dawn in a tented village just off the M20 motorway in Kent.

It’s lucky, then, that Hertfordshire teenager Lewis Hamilton doesn’t care whether there is a crowd of one or 100,000 there to bear witness to his first world-class drive as a professional racing driver. This is the most important day of the 17-year-old’s meteoric rise up the motorsport ladder, and that’s all that matters.

Except… it isn’t all that matters. Because Hamilton is special. The champion kart racer is the protégé of McLaren Formula One boss Ron Dennis, who believes he will soon be a grand prix driver. Hamilton is also black. And there has never been a black F1 driver.

If Hamilton makes it into F1 (and Dennis is not known for being careless with his cash), then this dull day near the Dartford Crossing will have been historic. If not, the early start will have netted nothing more than a bacon buttie.

Few of the early birds in the Formula Renault paddock at Brands Hatch know that Hamilton has barely slept. Most don’t care. They are preoccupied with finding that bacon sarnie and a mug of tea for breakfast. Hamilton’s stomach is churning too much to think about food. For the first time he is consumed with stage fright, opening night nerves. ‘I’ve never felt like this,’ he says. ‘Maybe it’s the damp, or the new clutch. I’m worried about stalling on the start.’

But Hamilton isn’t the only rookie trembling beneath the shadow of Brands’ blind walk-the-plank-at-100mph Paddock Hill bend. The grid of 36 cars is peppered with testosterone-charged teenagers trying to make the grade. Most barely look old enough to drive a pedal car. But this is the kindergarten from where Kimi Raikkonen smoked into the high-octane high school of F1.

Hamilton is not in Formula Renault by accident. He, his manager father Anthony and McLaren have picked it as the ideal launch pad to stardom. Running winged chassis and capable of 150mph, they are effectively mini F1 cars.

‘We will have to see how he develops, but right now I would imagine the plan is a year or two in Formula Renault, Formula 3 and then Formula 1,’ says McLaren managing director Martin Whitmarsh. ‘We have an expectation that he will drive an F1 car for us one day.’

Hamilton is not the product of positive discrimination. Black or not, he is arguably Britain’s brightest driving hope of his generation. Ever since he slipped behind the wheel of a kart at a holiday resort in Ibiza 12 years ago, Hamilton has left his rivals eating the dust and inhaling the burned rubber left in his wheel tracks. ‘When we got back from that holiday, Dad took me to a track near home,’ says Hamilton. ‘I was hooked.’

Like many West Indian families, the Hamiltons had no connection with motorsport. Buying Lewis a racing kart was a massive risk. ‘Before I knew what was happening, I had spent £10,000 on the kart, engines and equipment,’ Anthony recalls. ‘That was my annual salary at the time, so I was relying on credit cards and an overdraft. Luckily Lewis started winning from the first day he got into the kart and we have kept moving up.’

Hamilton’s career would have crashed as fast as it took off, were it not for the fact that Dennis happened to see Hamilton in action in a kart race five years ago. There and then, the multi-millionaire boss pledged to nurture Hamilton all the way to F1.

On the day Dennis’s offer came chuntering out of the fax machine, Hamilton just shrugged his shoulders and went upstairs to do his homework. ‘I was happy. I was excited. But I had no say,’ he recalls.

The material benefits of the deal were soon obvious. For five years the whole family travelled with Lewis to tracks in Britain and Europe aboard a luxurious American motorhome. It was not only a home from home but also acted as Hamilton’s classroom when racing meant missing days at school. Hamilton is now finishing off his A-levels, just in case. It is on the advice of both Dennis and Dad, who keeps working in his own computer company, should Lewis fail to lay the golden egg.

Anthony Hamilton is Lewis’s shadow. Some have called him the archetypal ‘touchline dad’, getting more wound up behind the barriers than his offspring in the thick of the action. But even with McLaren’s backing, motor racing is a shark pool. And at Brands Hatch, Anthony says he feels as if he is in the deep end.

‘In karting we knew everyone and everything, but this is the big time and it will take us a while to find our feet,’ he says, trying to exude some calm in a family clearly tensed up by Lewis’s apprehension. ‘The difference is, we know this step is a big one.’

Neither Anthony nor Lewis are shy about their racial roots. They make no attempt to exploit or suppress its bearing on the future. Both know it is not just family dreams weighing heavily on their shoulders.

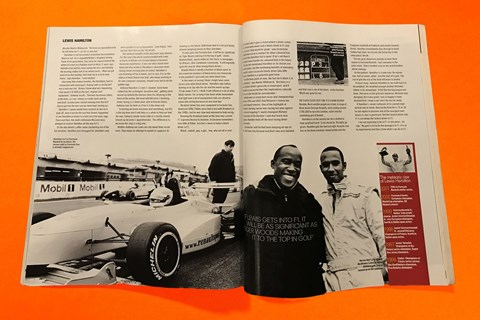

‘If Lewis gets into Formula One, it will be as significant as Tiger Woods making it to the top in golf,’ claims Rodney Hinds, sports editor at The Voice, a newspaper for Britain’s Afro-Caribbean community. ‘It will hopefully open the way for other young black drivers.’

Brands Hatch is hardly a bastion of black sport. In the crowd the number of black faces is minuscule. In the paddock I spot only one other black face.

‘In five years of racing I think I might have come across one other black driver,’ Hamilton says before leaving us to slip into his car and the warm-up laps. ‘If I do make it to F1, I think it will influence a lot of other black talents. For so long it has been white dominated and right now a lot of young black kids are afraid to come into racing because no-one else has.’

No black driver has ever competed in Formula One. American Willy T Ribbs once had a test with Brabham in the 1980s, but he was slow and returned to Indy racing.

Running the Brabham team at the time was current F1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone. Ecclestone remembers very little of Ribbs’ test but is keen to have a black driver in F1.

‘Black, Jewish, gay, a girl… hey, why not all in one! To be honest I don’t give a damn where a driver comes from, but we have never had a black driver in F1 and so, of course, that would be great,’ says Ecclestone. ‘It might then act as a catalyst for other coloured kids. But only if this Hamilton kid is good. If he’s not then it will make it even harder for coloured kids in the future.’

McLaren has nominated Hamilton as its chosen one on talent alone, but the marketing benefits of managing the world’s most successful black driver take little analysis. Hamilton is a potential gold mine.

‘From the team point of view, the fact he is black is of no relevance,’ says Martin Whitmarsh. ‘But there is a lack of black drivers generally in motorsport, and if Hamilton is successful then the implications culturally and as an icon would be considerable.’

Hamilton won so many kart races and championships between 1995 and 2001 that McLaren’s money has already reaped rewards. One of the highlights of Hamilton’s karting career was racing last year against his idol and reigning F1 world champion Michael Schumacher at the German’s own kart track near Cologne. Hamilton held off the best racing driver in the world.

‘Schumacher said he had been keeping an eye on me, that I was very focused and that I was very talented and that I was a star of the future,’ smiles Hamilton. ‘Which was great for me.’

The clock clicks past 9am. It is a bank holiday Monday. Most sensible people are in bed. A conga of three dozen Formula Renaults, each costing around £100,000 to race this summer, snake onto the undulating grid at Brands.

Hamilton is on the second row. He is chuffed to have qualified fourth. So he should be. The lights go green. Hamilton gets the start just right. He yanks into line as the three machines ahead tumble over the imaginary waterfall at Paddock and career towards Druids. Hamilton immediately slips through to third. Sixteen laps later, he crossed the finish line in the same place. Result.

‘The two guys ahead are already on their third season in Formula Renault,’ says someone in the press room. ‘Give it another race or two and Hamilton will be winning.’

On the podium, Hamilton is a new man. No nerves now. And no sweat, either. Just the start of a grin. The sort of grin the rest of the field will learn to loathe.

‘It wasn’t easy,’ defends Hamilton as we walk back to the paddock. His disabled younger brother Nicholas follows in his wheelchair. ‘It felt like the big league out there. The noise on the grid was immense. My heart was thumping. But it was great. I am so happy to have finished third. I hope a win won’t be too far away.’

If Hamilton’s career continues on its current near vertical rate of climb, then by the time he is 19 or 20 he can expect to become one of the youngest ever drivers to start a grand prix. But the fastest driver into F1 is not always the fastest driver in F1.

‘I am not expecting to be in F1 in two years,’ he says. ‘My goal is not to be the youngest in F1. It is to be experienced and then show what I can do in F1.’

The meteoric rise of Lewis Hamilton

- 2001 Fifth in Formula Renault winter series

- 2000 Formula A karts: European champion, World Cup champion, Elf Masters winner

- 1999 Intercontinental A: Italian ‘industrials’ champ. Junior Intercontinental A: vice-European champion, fourth in Italian open series

- 1998 Junior Intercontinental A: second McLaren Champions of Future, fourth in Italian open series

- 1997 Junior Yamaha: Champions of the Future series champion, Super One series champion

- 1996 Cadet: Champions of Future series winner, Sky KartMasters champion, Five Nations champion