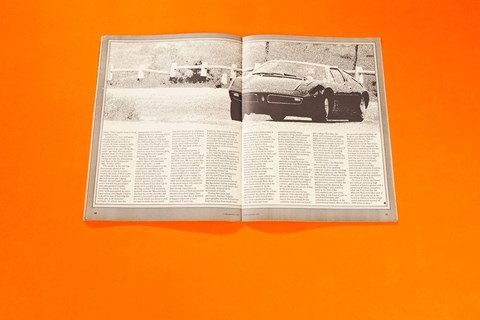

► Doug Blain drives the Maserati Bora

► Only one place for it, the moutain roads

► An archive gem from our new CAR+ service

Looking back at what I wrote about the Bora in January this year, I can hardly believe that the car I drove on my latest visit to Modena was from the same stable.

Not that I want to retract any of my more profound impressions. I still rate the model ‘a restful, practical, long-legged and very fast high-mileage two-seater’. My abiding memory is still of ‘a taut, responsive and yet undeniably luxurious’ car with an uncanny appetite for distances, as well as for expensive Italian petrol. The difference is simply that almost none of my original detail criticisms of the prototype apply to the production version, and I want to take this opportunity of making it quite clear that the Bora is one of the finest fast cars ever built.

The galling thing is that I only found this out by accident. Your editor and I were in Italy for a week after the Targa Florio, doing the rounds as usual, and we had set aside a day in expectation of being able to drive Maserati’s forthcoming ‘mini-Bora’, which a little bird had told us might be ready about that time. It wasn’t, but our good friend Dr Tarusio had arranged for us to have the company’s demonstration Bora for the afternoon instead. We arrived in good time, only to stumble over a comprehensively crunched example parked conspicuously outside the front door. And when you have known the Italian supercar factories for as long as I have you are left in no doubt what that means.

Dr T was one step ahead, however. Bursting into the waiting room with his hands spread in a gesture of despair, he blurted out wildly: ‘Meester Blain, I am so sorry…’ and then fell about laughing. True, the car outside was the demonstrator. True, the works driver had crunched it on the way up from Salerno the day before (twice for good measure, would you believe). But the genial Dr had bypassed the system and found us no less than three other cars to choose from, according to colour. As the choice was black, grey or purple we settled for the last even though it was the same as last time, sought out our favourite factory tester to sit in the passenger seat (keeps the insurers quiet, and he enjoys it) and headed for the hills.

Among my lesser gripes after last winter’s encounter, I see, was one about the change-speed mechanism for the five-speed ZF box located behind the engine and final drive. Now this is the same box that De Tomaso use for the Pantera, and it has been used in other mid-engined machinery including the daunting Monterverdi Hai. My experience of it has more or less convinced me that there was no way in which it could be made more than barely acceptable, and I knew full well that if the systems engineers failed to get their sums more or less dead right the result could be very nasty and even dangerous. But the latest Bora has a redesigned shift linkage, and the result is a revelation – smooth, precise movements between ratios, and no more effort required than one might expect in a front-engined car of this potency. Other designers who have despaired of translating the leverage of a man’s hand via a system of rods, levers and bell-cranks into a series of sliding and meshing movements in a hot, foam-filled container which is itself oscillating independently under torque reaction nearly six feet further rearward may take heart from Ing Alfieri’s achievement.

Then there was the problem of the steering. A rack and pinion set-up by ZF, it felt fine in the prototype at lowish speeds and on winding roads, but on the straight, and particularly on bumpy surfaces, it allowed too much wander. This I found hard to explain, although for some reason I remember feeling sure it was a steering problem – perhaps a geometrical one – rather than a question of instability arising through aerodynamic or other imblanace. Anyway, whatever it was it was short-lived, for once again the production model showed no sign of it. In fact no sooner had I got clear of Modena than I changed my mind about making off into the mountains and turned instead onto the Autostrada del Sole, thinking to discover whether my early impression of a tremendous improvement in the feel of the car held good at really high speed.

It was lunchtime, and the usual heavy traffic on the main north-south highway had abated a good deal. This argued well for conditions on the spur motorway from Bologna towards Ferrara, which is newer and much less frequented, and sure enough when we turned off the Bologna cintura the wide, straight road ahead of us was clear for miles and miles. I turned to my impassive companion and asked doubtfully whether I ought to extend the big 4.7-litre four-cam V8 all the way to the red line, admittedly conservatively positioned at a mere 5800rpm; I was very conscious that this was a brand-new car with only a few hours of bench-testing at the very most to its credit (the distance recorder said less than 200km!). But the mechanic wouldn’t hear of anything less than the full treatment. ‘Take it to 6250,’ he said, with a laconic wave of the hand. ‘They usually seem to hang together at that.’

I planted my foot, noting the change points as I went at roughly 50mph from first to second, 80 from second to third, 120 from third to fourth (two more ratios to go and 120 on the clock) and a whisker short of 150 as I pulled the lever smartly back into fifth, starting out into the shimmering heat haze on the horizon for signs of other traffic.

The needles in the two big instruments ahead of me continued to march steadily towards the end of their scales, and within seconds, it seemed, the tachometer was edging towards the red band. I glanced across towards my passenger, who only grinned broadly, mouthing the words, ‘Forza, forza,’ with appropriate gestures. I pressed on until finally I had to back off for fear of bursting the whole plot at an indicated 6200 rpm, by which time the presumably less truthful speedometer was showing almost 300km/h. Sober calculation afterwards against a fifth gear km per 1000rpm figure of 45.1 gave no less than 172.98mph, so even allowing for tyre expansion and a small margin for instrument error we must have been nudging 170 during those few magic moments in the red.

And they were magic, for the Maser felt uncannily stable and quiet – a stark contrast in these respects to the competition machinery and semi-racers (and Miuras!) in which I had attained such unnatural velocities before. On a trailing throttle, particularly, it held its speed so well with so little mechanical fuss that I quite forgot how quickly we were moving, so that I felt positively grateful when the Maserati man touched me on the shoulder and pointed about half a mile ahead to a truck which was about to pull out and overtake the inevitable Fiat 500. I had seen it, of course; and had planned to slow down in time to tuck gracefully in behind, but in fact it took us all of the available space to haul off so much speed without either setting the disc pads on fire or locking a wheel.

The latter phenomenon, I know, was one of my original grumbles, and I am still no fan of high-pressure hydraulics such as the Bora uses. My fear is not that the system will fail altogether (if it does, a dashboard warning light is supposed to give the alarm while the huge reservoir on the central bulkhead is claimed to hold enough reserve energy for more than 40 stops) as that the short travel and hypersensitivity of the pedal action will cause me to over-brake. Several hair-raising experiences in Citroens have convinced me that this is inclined to happen when one is least expecting it. I must say, however, that even in this I noticed a big improvement in the production Bora over the prototype, and it is only fair to record that in exchange for some anxiety one gets actual braking power of an enormously high order.

I managed to put in a good hour of hard charging up and down the unfrequented mountainsides of the Apennines before stopping for lunch in our usual haunt, the idyllically situated castle restaurant at Giulia.

Not that I would advise anybody, even now, to get too carried away in the Bora. It is an extremely solid and heavy hunk of machinery. It is powerful and responsive, and in common with many of its ilk it is fitted with a self-locking differential.

To the experienced this will suggest a measure of unpredictability in extremis, and it is so: hang the tail out, poke an exploratory toe into the last segment of the throttle pedal’s generous and well regulated travel, feel the locking device suddenly clench and unclench and – wham! You have the daddy and mummy of all mighty slides on your hands, and you will have to move fast to prevent the formidable weight in the tail from taking over. How do I know? I tried it once, and after I had sorted myself out (leaving great black marks all over the nice clean tarmac) my friend and the mechanic smiled and murmured, ‘Autobloccante…’

In this respect the Bora falls into a category of its own, between the ultra-sporting supercars such as the Miura, the Dino and the Pantera and the impeccably mannered front-engined grand tourers, most notably the Daytona and the Jarama. Its roadholding is very nearly as good as the best of the mid-engined cars, and at the same time it can boast at least as much performance and refinement as the finest of the conventional breed. Above all it is an enjoyable and rewarding car to drive just short of the limit. In view of which, and faced also with a high standard of finish together with a profusion of luxury amenities, what can I say but that the Bora now takes over as the most desirable car in the world in which to tackle a high-speed continental journey of 1000 miles or more?

In retrospect

No-one knew it, but in the mid ‘70s Maserati was reaching the end of a golden age. In 1975, it was on a par with Ferrari and Lamborghini. Only now, after almost 20 years in the wilderness, is the company re-emerging as a force. So the Bora is perceived as the last great Maserati, and as the marque’s stock raises again, so a good one could be a shrewd investment.

First seen in 1971, it was a rung below the Countach and Boxer. It was also a more subtle car, more sophisticated and significantly cheaper too, at £11473 in 1975. It was never shockingly quick – road tests spoke of 165mph and 0-60 in about 6.4 seconds – but it certainly looked and felt like a supercar.