► LJK Setright drives the Renault 5 Turbo

► The back story of the most Super of Cinqs

► An archive gem from the annals of CAR+

Although Jean Terramorsi disappeared Renault are giving him due credit, at least, for originating the idea of the R5 Turbo. He was one of their most fervent supporters of motorsport and one of the staunchest advocates of their participation in it.

His idea was for a sort of R5 silhouette hyper-sports car in which Renault could aim for top honours in international rallying. It was an idea that he dreamed up early in 1976 and work was started within a matter of weeks. All the design was Renault’s, but making the styling model was entrusted to Bertone. It meant a lot of traffic, for every time something was changed on the model, the shape had to be tested again – at the Dieppe factory, or in the wind tunnel at St Cyr.

Mechanically there was no doubt or hesitation in the designers’ minds. The car had to be the most proficient tarmac-rallier imaginable, with proper racing- style suspension – double wishbones at every corner – and a mass distribution that dictated a mid-engine layout. As for the engine, it looked as though 2.0 litres would be about right, and allowing for the 1.4 coefficient of equivalence whereby the rules of the sport declare that a turbocharged engine is to be reckoned as 40% more capacious than its actual cylinder displacement, the 1397cc Renault 5 Alpine (know to us as the Gordini) engine would be just right.

Everything would have to be just right, to match: the brakes would feature ventilated discs for all wheels, and the wheels themselves would be sized (differently at front and rear) to carry the latest and most appropriate tyres made in France, the high-speed Michelin TRX. Despite looking like a sort of R5, the car would naturally be a two-seater, which would help organise the weight distribution to better effect; but if, for the maintenance of that balance, it were necessary to put the petrol at the centre of gravity, under the crewmen’s seats, then it would be put there. And it was.

Renault 5 Turbo: a very hardcore kind of hot hatch

It was a serious competition-orientated job, originally with no thought of selling the car to the general public. That came later. After all, they would have to build 400 of the things if they wanted homologation in Group Four; why not make the most of the modest production facilities at Dieppe, which could make five a day – call it a thousand a year? France is fond of the R5, the best-selling of all French cars, with a daily production in all its 10 current versions of 2400; the R5 Turbo could be a new pinnacle to that pyramid, as well as giving Renault the chance to accomplish in rallying what they have already done at Le Mans and in Formula One.

Essentially for the French market, the R5 Turbo is not scheduled for the land of the UK, and it may never come here. It went on sale in France on July 1 and will enter the Italian and German markets in November. Switzerland, Holland, Belgium and Austria will have it early in 1981 and by that time, customers will be able to ask for some of the modifications that will make them competitive in rallying. The works car (lighter, and with 250bhp compared with the 160 of the production version) will make its debut later, probably in the Tour of Corsica.

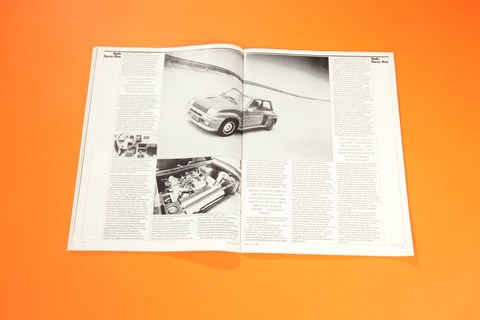

Such a power output cannot fail to make so well-balanced and carefully-suspended a car a brilliant performer on the road, being so compact and light. How the power is obtained is worthy of study: drawing on their racing experience (which in turn drew on a fund engineering practice) Renault have inserted an intercooler: between the turbocompressor and the engine inlet manifold. An air-to-air heat exchanger, it reduces the temperature and thus increases the density of the charge, which is inevitably heated by the compressor, even though the adiabatic efficiency of the Garrett T3 turbocharger is quite respectable.

Maximum boost pressure is 12.2psi requiring a compression-ratio reduction to seven-to-one, and this produces a brake mean effective pressure of 275psi, translated into a peak torque value of 155lb ft at 3250rpm. Peak power figures are scarcely less impressive, the 160bhp realised at 6000rpm (the redline is at 6500) representing a bmep of 248psi.

That intercooler evidently works well. It is particularly desirable in a turbochargjng installation where ho evaporative cooling of the charge air can be accomplished by correct placing of the carburettor; the Renault has no carburettor. Fuel surge problems would make any carburettor a handicap in a car with the cornering power of the R5 Turbo; instead, as (and for the same reason as) in all racing cars, the fuel is delivered by injection. A mechanical system, the Bosch K-Jetronic, was chosen, the throttle butterfly situated downstream from the compressor.

What the engine gives, the wheels take through a five-speed gearbox derived from the R30TX and producing 32, 52, 77, 101 and 123mph at 6000rpm in each gear in turn. Interesting is the clutch, a twin-plate device only 7.5 inches in diameter. Most interesting are the tyres which, being TRX, have their own special and odd sizes. The front wheels are 5.5in wide and 13.4in diameter, the rear wheels (they do the driving, remember): are 7.7×14.4in; and they are shod with 190/55 HR340 tyres at the front and 220/55 VR365 at the rear.

An outrageous fast Renault

Looking at the car you might agree that despite all its plastics flares and spoilers it looks every inch a Renault; looking at the running gear, you must agree that it is every millimetre a racer. If you could measure the weight distribution, you would find all the confirmation you could ask; the kerbweight of 2T38tb is shared 40/60 front/rear, but the laden weight comes out even better at 44/56.

Such balance reveals itself on the road as contributory to the most amazing roadholding and handling. Before I drove the Turbo, I talked with Alain Serpaggi, the erstwhile racing driver who is now a Renault test driver and who was first and foremost in the development driving of this car; and he spoke of braking at 1.1 g, of cornering at 1.8g, and of suspension that had been endowed with progressive rate (but always firm) springing so as to ensure adhesion and stability (notably freedom from excessive pitch) despite a wheel travel of less than two inches from static laden to full bump, with a periodicity of 1.5Hz.

As he spoke, so he drove, with the complete authority of a man who knows his car inside out. I followed him over the last three miles of a 90-mile test route that had snapped and swung through some of the most dramatic of French Alpine valleys: he clearly knew the roads as well as he knew the car, and to watch his squat Turbo streaking up the hills ahead of me and sliding at full audible screech through the tighter corners it seemed astonishing – and no less astonishing that mine must have been doing the same, for it did not feel particularly exciting. That is one of the virtues of the Turbo 5 – of the customer version, that is.

What it feels like to drive the Super Cinq

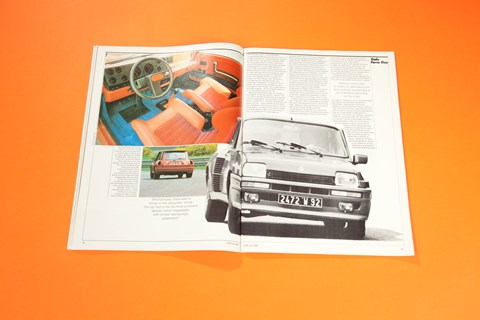

Inside, all is smooth and quiet and comfortable – not absolutely, but admirably. The seats are shallow in their cushioning, because they have to but they feel soft because they are designed to support. For me, legroom was insufficient, so my thighs could not rest between the side bolsters of the seat cushion as its designer intended. Nevertheless the pedals fell as readily to foot as in anything I have driven for years, so neatly that it would have been hard not to heel-and-toe for each downward shift through the R30TX five- speed gearbox. The steering wheel was in the right place too, cleverly styled and feeling very good in the hands – and this is a car in which you use your hands to steer, not your fingertips.

At such speeds as this Turbo can reach, you need to use your eyes, too; and you need them for the road, most of the time. The 10 dials on the fascia are well placed for quick reference, but very difficult to read in daylight. They have orange markings, and they are lit whenever the ignition is switched on; but a faint patina of dust, or the sun over one’s shoulder, makes the markings almost disappear. That is their only fault, albeit a serious one, and the speedometer in particular deserves high praise. Reading signals from an electromagnetic sensor which counts the turns of one front wheel, it is as accurate as tyre wear allows; at 180km/h, the error was three-tenths of one percent.

I could therefore believe the 200km/h that was held steadily for some miles of slightly uphill and markedly swervy motorway. Renault say that 200 was top whack on the banking at Montlhery, but that on a level road it can climb to 206 or 208, which is about 129mph. It is not bad for 160bhp: the R5 Turbo may be low and light, but its breadth gives it a substantial frontal area and its shape gives it a drag coefficient which is quite disgusting, about 0.46, in exchange for unquestionable stability at all speeds.

A car that answers the helm so fast and so positively brings a new meaning to directional stability. One of the many hairpins en route was strewn with gravel that hid in the sun’s glare, and as I put on the power the car flung itself sideways as though to dodge one of Jove’s bolts. It was not a twitch of the wheel, not a flick nor a swing, but a snap of the steering that had the car instantly on line again. Only a couple of times did the front drift out slightly as I lifted my foot in the entry to a bend.

Only with full boost in a low gear did the rear try to wriggle and break out of the unrelenting grip of those hard-rubbered TRX Michelins. Otherwise, the car was simply capable of cornering faster than conditions would allow. There were no roundabouts on which to play games and try conclusions, few fast open bends through which to learn now insensitive the steering is to the throttle, only a countless succession of tight corners uphill; downhill, in and out of tunnels, with cows before and camions beyond. It was a good route for gearchanging practice, for proving that the brakes get better as they get hotter and will surely never fade, and for confirming once again the problems of response from a turbocharged engine.

With its intercooler and injection, this must be one of the two or three best turbo jobs in production, and in view of their competition plans Renault were right to choose turbocharging for the sheer power it can liberate. As a road car, it would have been nicer with the R30 V6 engine that they considered as an alternative; but that fashionable word ‘Turbo’ blazed along the car’s fat flanks will attract far more buyers than will ever go for the V6-powered Alpine 310 Berlinetta, a car that is better shaped and has even less room for luggage than this R5.

Why quibble over the slightly inadequate ventilation or the loose feeling of the super structure? It is a sports car, and one that earns its status. It can take a corner 40percent faster than most things on the road, accelerate out of it faster, brake harder for the next one, and with more than 20 gallons of petrol in its tanks it can go on doing it tirelessly for a very long way. Never mind the quibbles, the car itself is marvelous for the road – any road.

Click here to read more CAR+ Iconic Car tales