► Mel Nichols drives the Ferrari Daytona

► V12 blasts through the Welsh valleys

► Another iconic car in our new CAR+ service

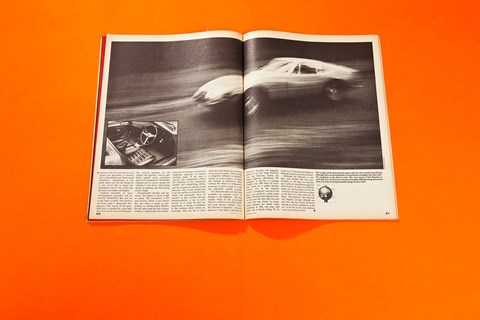

We came over the crest and into the valley and there ahead of us lay an open, loping stretch of road. It dropped gently, ran flat and diagonally across the valley’s far rim. Before it reached the top there was a bend that flicked it suddenly to the right, so that it then ran square-on up on to the rim. The Daytona had been in full flight for miles; this was more grist to its mill, and we swooped down into that pretty little valley with the nose lifting and the V12’s yowl bellowing out behind us. Second ran out at 86mph, third gave 116mph at the same 7700rpm redline and then we were pushing forward furiously in fourth.

The bend, the high-speed kink, loomed. We’d be doing around 130mph when we reached it; 6800rpm or so in fourth. Around 340bhp coming from the engine. If I kept my foot flat, there would almost certainly be oversteer. But how much oversteer? How suddenly would it come; how savagely? What does a Daytona do when it lets go at 130mph? How do you ring its owner and tell him you’ve overcooked it and his Daytona’s laying shattered at the far end of a field deep in Dorset? Should I try it or not? My mind raced with apprehension.

But there was something, something discovered in the days and miles between awesome expectation of driving the Daytona and comfortable familiarity with it that said it would be all right; and I could not resist. The throttle stayed flat, the six Webers wide-open, the exhausts thundering and very soon the car was at the turn-in point and there was no longer time for anxiety.

There was an obvious line and the Daytona came onto it with now-familiar but ever-impressive alacrity; you just need a firm mind and hands firm upon the wheel. The inside wheels clipped the apex. The nose began to drive outwards again to the far side of the road. And in the same instant, there it was! The rear tyres let go and slid, and in the very split second that they let go, I knew. The message was delivered to me as clearly as if it had been the seat of my trousers itself that was touching the road. Somehow even as it happened and spanning so minute a slice of time as it did, I had time to wonder how much the wheels might go on to slide. But then there was the quick flick of the wrists to wrap on a twist of opposite lock at the leather-rimmed wheel – just the one quick, instinctive, parsimonious flick – and the tail came back, as flatly and as precisely and as positively as it had broken away. In my peripheral vision I’d seen Colin Curwood’s right hand snap out to grasp the handle, and then withdrew again as he too felt that it was all right. We didn’t even need the full width of the road for the exit. The Daytona just swept a couple of feet out from the road’s inside edge, lined itself up as the wheel was neutralised and stormed onwards, heading straight as a die for the crest, with fourth, too, almost running to its 146mph limit before there was call for the brakes.

There were other sublime moments, plenty of them, during my time this winter with Nick Mason’s 1972 Ferrari 365GTB4 Daytona. There was the awesomeness of the ease with which, when the traffic cleared momentarily on the motorway, it whisked me to 165mph and so obviously had more to give had I not been forced to lift off. There was the pure thrill to be had, so many times, of unleashing the sort of power that brings up 60mph in 5.5sec and 100 in a little over 12 sec. There was the satisfaction, after a long fast drive, of switching it off and remaining in it, listening to the ticking metal cooling down, and recalling the miles. There was the prolonged, adrenalin-filled high of balancing it finely, against the wheel and plenty of second gear power, through one of the long and open bends we found that looked so good for Colin’s pictures. But the climax was that lone left-hand kink. There, for me, the Daytona told its story. There, it despatched the last of the suspicion that had been implanted in my mind by the mythology and that has accompanied its passage through the ‘70s and into immortality. A monster a great big old brute of a thing that goes like crazy and must be treated, the myth seemed to have it, with extreme caution if not downright trepidation. But the Daytona is not like that.

It arrived late in 1968 to a mixed, even mildly disparaging reception. Some acclaimed its styling as a masterpiece from the outset; others criticised the wide glass panel that covered the four headlights as being silly and impractical (later, mostly for legal reasons, the arrangement would be changed to the twin sets of pop-up headlights that were to stay with the Daytona until units demise in 1974). But most of the reaction against the Daytona stemmed from those who had expected Ferrari to allow the little Dino 206GT and to answer the challenge of the Lamborghini Miura with an all-out mid-engined two-seater. The ultimate Ferrari, they pouted, should be of the ultimate technical form. But Enzo Ferrari has often lagged in his adoption of technical novelties. Maranello’s path, so often, has been a traditional one pursued to the upper reaches of development, with the wind of change growing irresistibly strong before the course has been altered. The Daytona’s critics probably cared not to consider perspectives: that the 4.4litre 365series engine had been developed for use in an assortment of front-engined cars, that there was considerable lead time, that Maranello had an engine and chassis design that they obviously liked very much and a body styled by Pininfarina to which they were also, undoubtedly, very attracted. There are many clear and supportable reasons why Ferrari laid down the Daytona the way they did; but when it’s all boiled down, the core of the matter is that in the mid-‘60s, for their big grand touring road cars, Ferrari’s belief rested firmly with the front-engined layout, its development and its refinement. There would be one more all-out front-engined Ferrari two-seater of the traditional mould. And it would have capability sufficient to deal with the upstart Miura from the other side of Modena, loudly hailed as the machine that had taken the wind out of Ferrari’s sails. A neat 300km/h – 186mph – had been claimed for the mid-engined Miura, but around 172mph was nearer the mark until the SV came along later. Ferrari just said that the Daytona would reach 280km/h – 174mph – and it wasn’t to be all that long before independent testers proved that they were not exaggerating.

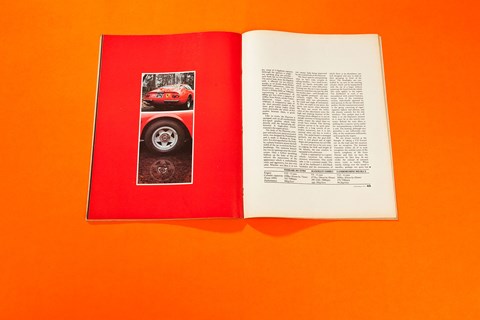

There is as much purity as individuality in the Daytona’s styling. Nothing else conveys the long-bonnet, small cabin, chopped-tail slingshot look as dramatically, and if the proportioning us uncomfortable to the eye then walk up close and let the eye feast upon the deliciousness of the car’s detail, the sultriness of its curves and the way they go together to make the whole. Stand back again and consider that this car, weighing 3500lb dry, is sufficiently slippery to permit not only a top speed of 174mph but upper-end acceleration in fourth and fifth that is still unequalled in a road car except perhaps by a perfectly tuned Countach S (and no one will know for sure which is the faster until someone manages to run an S against the stop-watch). And consider that, without the merest trace of a spoiler, the Daytona is impeccable stable.

The Daytona replaced the Ferrari 275GTB4, and was very much a development of it. Its steel body, built by Scaglietti to Pininfarina’s design, was bolted onto a similar sort of tubular steel chassis frame and the wheelbase, at 94.5inc, was identical. But the Daytona benefitted from wider 56.6 and 56.1in tracks. Its suspension is Italian conventional, a system proved time and again to work exceptionally well: upper and lower wishbones with coil springs, telescopic dampers and an anti-roll bar at the front, with another set of upper and lower wishbones, more coil springs, telescopic dampers and another anti-roll bar at the rear. The steering is worm and nut, the brakes 11.4 and 11.7in ventilated Girling discs and twin circuitry and servo assistance. The classic wheels, to become known as ‘Daytona-pattern’, are cast alloy, centre-locked onto splined axles, carrying 215/70 by 15 Michelin XVRs.

To help balance the car as finely as possible, Ferrari mounted the engine a long way back in the chassis, almost all of it behind the front axle line. They went further: the transmission was despatched the rear, in unit with the differential, and linked by drive shaft and torque tube to the engine and clutch. All five gears in the transmission are indirect, running from firsts 3.07 through a 2.12 second, 1.57 third and 1.25 fourth to a 0.96 fifth. The final drive ratio is a well-balanced 3.3 to one giving 23.7mph/1000rpm in fifth.

The Daytona’s engine is a member of Ferrari’s classic road-going V12 family, and descended directly from the 3.3litre four-cam 12 of the 275GTB4. The angle between the cylinder banks is 60deg, the bore and stroke 81mm by 71mm, giving a totally capacity of 4390cc. The crankcase and block are cast in silumin, with shrunk-in liners, and the fully-machined crank runs in seven bearings. The compression ratio is 9.3 to one; there are two camshafts on each cylinder head, six downdraught Weber carburettors, twin coils and distributors and, at the bottom end, a dry sump. From this engine, running on 100-octane fuel, comes nothing less than 352DINbhp to 7500rpm. And from it flows massive torque. It peaks at 318lb.ft at 5500 rpm but the curve is so flat and hefty that even at 1000rpm there is almost 190lb/ft, and everywhere from 2000rpm to 7000pm something in excess of 260lb/ft is available.

The Daytona is long and fairly low – 14ft 6in by 49in – and you hook a finger behind those strange little catches on the top of its doors and swing them out and drop down into its cabin; into seats like old-style racing buckets which hug the body cosily and say that they will have the ability to keep you in place when the car is going hard about its business. The driver is faced with an alloy-spoked and leather-rimmed wheel, with a large metal boss that encircles the vaunted black-on-yellow prancing horse horn button. It is connected to twin Fiam air horns. The wheel, whose flat spokes are drilled, is moderately raked, somehow very business-like and yet somehow casual too. The hands just drop onto its rim comfortably; perfectly. Through it, enclosed within one oval and deeply hooded pod, are the instruments – the vast matching tachometer and speedo, with the four most important of the minor gauges grouped between them. You see all of them well enough; best of all, you are never in any doubt about whereabouts of tachometer needle.

In the corners of this big binnacle are two final gauges: on the driver’s left, the fuel gauge and on his right, a clock. All the gauges are black-rimmed, standing out from the metal panel that carries them. They reflect a little in some lighting conditions. Overall, they have a certain flair and appeal that does not interfere with their efficiency; and if they are less stylish than some other Ferrari gauges they are also more efficient and more easily read than most of them. There is a small lever on the steering column for the indicators, behind it a larger one that controls all the headlight functions.

On the other side of the column there’s another stalk to work the two-speed wipers and electric washers. Three sit in the centre of the dash, outside the main instrument binnacle, to control individually the heat supply to each side of the car and to regulate the temperature. Toggles below them switch on the heated rear window and the hazard flashers. On the flat-topped central console, down near the base of the gearlever, are rocker switches for the electric windows. Like the radio, the cigarette lighter and ashtray are dropped into the tunnel cover; not after-thoughts but accorded a casualness that indicates their standing in this particular cockpit.

The gearlever is tall and spindly, unbooted, sprouting from one of those marvellous open Ferrari gates. Its height means that the arm need simply extended to it, not drop to it, and that the hand does not have to move far from the wheel’s rim to seize it.

When the arms are comfortable at wheel and gearlever, the legs extend forward with just a little bending at the knees too big, manly, business-like pedals. The clutch does not travel very far, and if it is not light it is not ridiculously heavy either; it is simply what you expect. Put the right foot on the brake pedal, and feel with the outer edge of it the tall throttle pedal. The proximity of the two for toeing and heeling is perfect.

There is a closeness about the Daytona’s cabin that helps the driver feel in tune with it, part of it, and not overwhelmed by it. The roof is small above the head, and the windscreen and side windows curve well in to meet it, so that at the same time they feel as if they curve in around the head; you wear this car. And if the long bonnet appears from the outside as though it will be ungainly and difficult to see and to place, it is not like that from the driver’s seat. It is not possible to see all of it – just to a point beyond those outlet vents – but it doesn’t matter; it does not take long to a sense its extremities and to feel at ease with them. And nor – and this is the truly marvellous thing about the Daytona – does it take long to know and understand and feel at ease with all its extraordinary performance. It is there to work with you (if not exactly for you, for it could never be servile, this car) but it is never there to intimidate you.

Pump the throttle a couple of times on a cold morning, even a morning with ice on the ground, then turn the key and the v12 will fire immediately. And from its first beat it runs evenly, without snapping or popping or missing. It is ready to be driven away, asking nor needing nothing more than due respect by the way of warm-up. The gears need to be shifted slowly and deliberately, for the oil stays thick in the isolated transmission for a long time – for 10 or even 15 miles. After that, the lever will shift quickly and cleanly, and with considerable pleasure for the palm of the hand and the section of the mind that controls it (although there is never the sort of pleasure that is to be found in the Ferrari’s with front-mounted transmissions). Such is the precision of the throttle and the fine, measured response of the engine to it that even when the roads are very slippery with water or frost it is easy enough to mete out the power so that the rear tyres do not spin. The Daytona just gets on with it, efficiently. Push too hard on the throttle and the wheels will spin crazily, the tail snapping instantly and massively sideways; you will be somewhere between 45 and 90deg to the direction of travel at a stroke. Ah, but such is the Daytona’s inherent balance and stability that releasing the power and snapping on a bite of opposite lock will bring it back perfectly into line. Knowledge of that sort of controllability makes it easy to live with whatever the road surface, makes it easy to come to grips with the power on hand, and to know that that power is there to be used.

And with knowledge of the communication that is there in the chassis, coming through the seat of the pants and the palms of the hands and somehow even the soles of the feet, it is possible always to extract the optimum level of performance. You just bring on enough power until you sense or are told that there will be loss of traction and, with the totes, you re-adjust. What will surprise you perhaps is just how much of the performance you can use even on slippery surfaces.

On a dry surface, the first unleashing of the full acceleration is electrifying, for it is neck-snapping. But the mind adjusts quickly and thereafter, while always thrilling, even stunning, it is temptingly useable. It is simply part of the Daytona. More than anything, more even that 0-60mph in 5.5sec and 0-100mph in 12.5sec, it is the span of the performance that is enticing. First runs to 59mph at 7700rpm, second to 86, third to 116, fourth to 146, and yes, fifth will go to 174mph at just under 7400rpm. Going up through those gears, there is just one long, sustained thrusting forwards. And then there is the pure in-gear performance, where that incredible torque provides 70 to 90mph overtaking, for instance, in just over 3.0sec in third, or 4.0sec in fourth and only 5.5sec in fifth. Just push on the throttle in the Daytona, and you go. Even at 140mph in fifth there is a solid push in the back, and you will be at 160mph within 15sec. And all the while the Daytona feels so secure within your hands, never that it is fighting to get away. It just has too much inner certainty of its own, this car, ever to be nasty or fussy. It is set up to maintain a very slight touch of understeer, just enough to be detected in the wheel angles in pictures and to be felt at the steering wheel by way of a steady tug in a bend taken hard. It can be neutralised with power; and the best way to corner the Daytona is to come into a bend fractionally below what might be the possible entry speed, let it settle momentarily and then steadily squeeze on the power. You will feel the car balance out; you will feel it simply sweep around the bend on the line you have selected. Bring on some more power if you wish to tip the balance the other way, when you are going sufficiently fast in a high gear or are in a low gear in a slow bend, and you will feel the tail begin to go a little light and then edge into a sort of oversteer attitude. More power and it will let go altogether, quickly, and you will have to get I back with the wheel or by lifting off; never fear, it will come straight if you are as decisive as the car itself.

It is a positive, finely-controlled car to drive, yes; but it is not a light car. It requires a certain physical effort, for its steering is not power assisted and although the brakes are assisted they require a pretty hefty shove to be made to work hard. And the clutch is not for feeble legs. But the efforts all match, and you are not aware of them intruding upon your pleasure. They, too, are just part of the Daytona.

So you feel at one with the Daytona, and you learn to revel in its performance and its possibilities; to use it. And it is perhaps the fact that you can find its limits and take it to them again and again with confidence that makes it so special in a world where the cars that have taken over from it are mid-engined. Their limits, those of the Boxer and the Countach, are higher in terms of pure cornering power and they are harder to find and even harder again to play with. If they let go, you do not get them back so easily. Perhaps that is why, magnificent and mellifluous achievement though the Boxer is, there were so many tales of die-hard Ferrari owners switching back from Boxers to Daytonas in the first few years of the BB’s life. You don’t mess with a Boxer, unless you are very, very good; you can do it with a Daytona. The Boxer is more refined, more comfortable, more of an achievement because it combines those virtues with its fantastic performance. But is it any more exciting, any more rewarding? The answer is that it is not, for one cannot achieve quite that same one-ness with the car as is possible with the Daytona.

Some passengers may perhaps consider the Daytona’s ride overly firm at low speeds; anyone who has savoured its performance to the full undoubtedly would not. In any case, in almost every other way it is not possible to fault the Daytona (forget fine finish, or rustproofing or 12,000mile servicing; you do not expect those things in this sort of Ferrari). Liken it, if you want, to a shark for more than the obvious visual reasons. The shark, biologists will have it, stopped developing 20million years ago because it could not be improved; it has reached a level of perfect efficiency. When the high-performance tide turned in favour of the mid-engined car it left the Daytona stranded; it left it stranded on a patch of high ground that will never, it now seems sure, be trodden by another, In the development of the front-engined ultra-high performing two-seater road car, the Daytona is the ultimate. And, like the shark, it is transcending time.