► Three amazing cars, five days, one adventure

► Alfa Romeo 8C, Ferrari Scuderia, Maser Granturismo

► An epic adventure drive from CAR+ archives

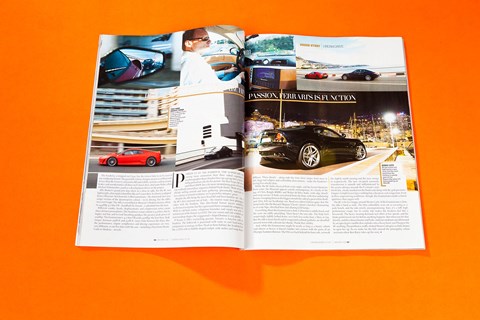

The white stretch of road dives steeply to the Fairmont Hotel. Getting the hairpin wrong would spectacularly embody the phrase ‘checking out’. Cuff the aluminium brake pedal and the red calipers bite, the revvy howl of the V8 behind the cockpit dips, and swing the wheel hard left. The steering is light and quick and the Ferrari’s nose follows in an instant, despatching the hairpin again.

At this far eastern point of Monaco’s grand prix circuit, it’s a right at Loews corner to join the straight that flows into the tunnel. On the left laps the Mediterranean sea. Floor the throttle, and the exhaust note has the intensity of a pneumatic drill, the buzz of a locust plague, a soundwave making the cabin resonate and tremble. The red shift lights blink within the wheel’s carbonfibre top section. Time to change up. A twitch of finger on the right paddle engages third gear. Even with the engine at full-bore, swapping cogs is instantaneous, natural, undramatic.

Into the tunnel, and at the kerbside stand concrete block sentries, guarding the pedestrian walkway and tunnel support pillars. But today, they house none of the towering armco of race day. It’s Tuesday – not Sunday – lunchtime and, despite 30 seconds of fantasising, I’m not Kimi Räikönnen. Nor am I driving Ferrari’s Formula 1 car, but the next best thing: the 430 Scuderia. Reality is a 30mph conga of swarming scooters, Peugeot and Opel hatchbacks. Oh, and Italy’s two other latest and greatest sports cars, the Alfa 8C Competizione and Maserati Granturismo.

Monte Carlo is Europe’s Las Vegas, and they have more in common than gambling, warm climates and service industry personnel expecting a hearty tip. Both places are united by a sense of the otherworldly, the unreal. The rising sun casts an unusual peachy glow over Monte Carlo’s towering blocks of pastel-coloured apartments and hotels, which house most of the 30,000 residents (none of whom pay income tax, unless they’re French). And the volume of exotic cars is truly exceptional: in one day, I spot two Ferrari 612 Scagliettis and three F430s, five Bentleys, two Merc CLs, a Lamborghini Gallardo and a Maybach.

And Monaco, of course, squirrels away an unusual amount of motorsport. The World Rally Championship kicks off with the Monte, and the F1 circus arrives early each season. Credit Anthony Noghès, the director general of the Automobile Club de Monaco. The motorsport-mad 1920s administrator conceived a race through the resort’s streets to attract tourists. The inaugural event took place in 1929.

On the 1950 Monaco grid, Alfa Romeo lined up against Ferrari and Maserati, plus four other teams. The race marked Alfa’s return to competitive motorsport after a brief hiatus, with the legendary Juan Manuel Fangio at the wheel of the 158. A few years previously, Enzo Ferrari had run Alfa’s racing team; in 1950, his four-year non-compete clause over, Ferrari took on his former employer, with Alberto Ascari among his drivers. The first lap was spectacular. Fangio led. Behind him, a wave crashed over the sea wall and flooded the road. Farina and Fagioli, Fangio’s Alfa co-drivers, skidded and blocked the road, and ten cars ploughed into them. Ascari’s Ferrari 125 made it through, but he couldn’t catch Fangio. The Alfa claimed first, followed by Ascari’s Ferrari and the Maserati 4CLT/48 of Louis Chiron. A 1-2-3 for Italy, and the inspiration for this story.

Now, 57 years on, the three marques have evolved from rivals to allies, united under the ownership of Fiat. All three are intertwined and their latest, rear-drive sports cars – the Alfa 8C, Maserati Granturismo and Ferrari Scuderia – have a common heart: their V8 engine.

The Scuderia, a stripped-out F430, has the closest links to an F1 racer of any roadgoing Ferrari. The gearshift (whose changes are just 20 milliseconds slower than an F1 car’s), electronic diff and stability systems, carbon ceramic brakes and aerodynamics all draw on F1 know-how. And Michael Schumacher helped develop this car.

Alfa Romeo’s grand prix days ended in 1985, but the 8C uses lightweight, ultra-rigid carbonfibre like an F1 racer does. Its chassis is adopted from a Maserati. Not from the £78k Granturismo featured here, but the older, two-seat Coupé. The Alfa is assembled at Maserati’s Modena factory, and fitted with the 444bhp 4.7-litre V8, handbuilt by Ferrari.

Different cranks, heads, displacements and compression ratios create three distinct powerplants. The Scuderia’s swept volume is 4.3 litres, but its higher red line and revised breathing produce the greatest peak power of 503bhp. The Granturismo’s 4.2-litre V8 yields 400bhp, the least here. Peak torque, between 339lb ft and 352lb ft, varies little between the three. But the performance, engine symphonies and driving experiences are very different, as our five-day blast from Monte to Modena – reveals.

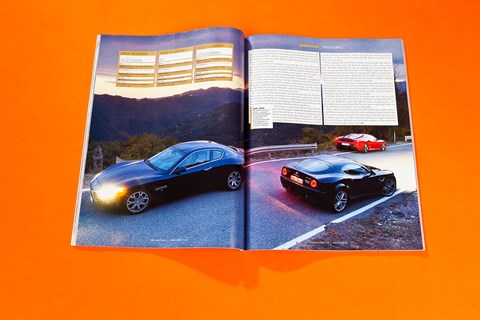

Parked up at the harbour, the supercars are causing a commotion. As our photographer lines up a group shot, a scooter-riding policeman asks for his permit. On that Vespa, he’s more spud than CHiPS, but a far more intimidating second cop suddenly materialises, impassive behind black shades. With 20 tourists already milling around and more gathering, we’re given five minutes’ grace.

Despite the Alfa being the most beautiful and least familiar car – this is the 8C’s first excursion out of Italy – the tourists want their picture taken with the Scuderia. Everyone knows Ferrari, but the cognoscenti loiter around the compact Alfa. With its cab-back stance, voluptuous haunches and simple rear end, it’s reminiscent of the Ferrari 250 GTO. The exaggerated v-shaped bonnet is very phallic.

If beauty is Alfa’s overarching passion, Ferrari’s is function. The bodywork is punctured with vents to cool hard-working components or manage air flow. From behind, the Scuderia looks like a UFO, with its bubble-shaped cockpit, wide arches and wing-shaped diffuser. While the 8C looks classical from every angle, and the Ferrari futuristic from some, the Maserati is pure contemporary, with edgy details and crisp creases. It looks ace from the front, with that undulating bonnet swooping down to a great white shark mouth. The rear is all wide hips, chiselled boot and LED lamps.

Everything about the Granturismo is firm. Cabin trim is solidly fused, and the seats are unyielding. Then there’s the taut ride. The body feels tightly lashed down – less cushy than a Merc or Jag. But the ride is never harsh and it’s exquisitely refined. It might be nearly as long as a luxury saloon and almost as heavy, but it handles. The V8 is set back behind the front axle, so tweak the slightly numb steering and the nose swings in responsively. The new six-speed auto transmission is smooth and unflummoxed by the erratic advance towards the F1 circuit’s start-finish line, clearly marked on the boulevard along with the grid positions. The Maserati feels happy here, but the 8C less so. The thin carbonfibre seats are as cosseting as a park bench, and the ride is uncompromising. Its crashy ride makes the Scuderia feel like a hovercraft. The heavy steering demands real effort at low speeds, and the brake pedal travels too far before anything happens. But when you hit that throttle, and the exhaust booms and barks, you’ll forgive the 8C anything. Traffic-choked Monte doesn’t suit it. So we make for the hills.

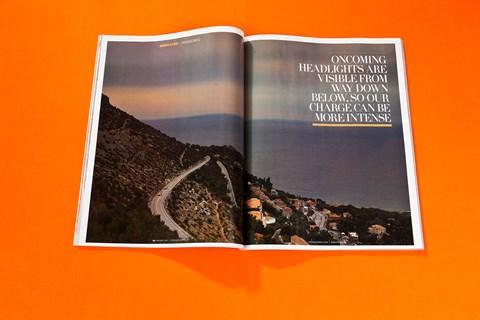

Our three cars push out beyond the clogged streets, shrugging off the crowds and latch briefly onto the A8, destination Genoa. We head inland at San Remo and climb deep into the hills, swooping along narrow roads cut into wooded hillsides. Flashes of predatory headlights catch in rear-view mirrors, pulses race, rear light clusters flicker. The road winds, climbs, twists, falls. Three engine notes ricochet off bleached stone walls: the Scuderia’s monotone blare; the crackle-pop of the 8C; the Granturismo’s muted crescendo.

In the time it takes to cover ten miles in rush-hour London, we’ve left everything behind. Up here it’s a world away from the excess and glamour of the principality. Mirror-fronted hotels are replaced by dilapidated buildings; sharp suits give way to faded jeans; manicured gardens cede to sprawling vineyards. This is WRC territory, the actual rally stages. There’s little margin for error – it’s a long way down.

The Maserati should be out of its depth here, but it works surprisingly well. Its damped-down responses – the finger-light steering, the gentle gearchanges, the softer ride – create an organic flow, an easy speed. A respite from the edgier, more urgent Ferrari and Alfa. Body roll and a lack of power let the Maser down, but this is a refined GT, one that really can move four grown-ups across country at discreet speed in complete comfort. It’s the cheapest car here, the most understated and the easiest to live with.

Of our trio, it’s the 8C that begs the most thorough examination. It’s a dramatic step from current Alfas, whereas the Maserati and Ferrari simply build on what already exists. It’s the biggest surprise, the biggest risk – a £111k car from a manufacturer whose next most expensive model costs just £31k. It’s also the most beautiful.

The car may look retro, but don’t be fooled. The bodyshell is steel, but the bonnet, wings and doors are constructed from lightweight, expensive carbon. Even the rear haunches are clothed in black weave. Climb inside and the remixing of traditional Alfa craftsmanship with up-to-the-minute technology continues. Low-slung carbon bucket seats are trimmed in tan leather, the stitching intricate and perfect. The dashtop is a solid hulk of carbon, with a monolithic slab of aluminium set inside – its blocky dimensions and triple air vents recalling great Alfas past. Adjust the central controls and feel the engineered-in heft, the machined touch surfaces. The wheel feels thin, solid, tactile. The curved carbon paddles poke from behind it.

Press down on the engine start button and the 4.7-litre V8 spins to life, idling with a bassy growl. Press the brake, tip back the right-hand paddle to select first and move off, noting that the rear differential locks up easily as you exit T-junctions. The vocal exhaust goads you to up the pace, to indulge the most diverse sonic repertoire of our trio. You make tentative progress, tickling the throttle, stability systems engaged, inputs over-cautious. Then the striking red of a Ferrari homes in from behind and adrenaline kicks in. Drop to second, a whip-crack fires from the exhaust and the 8C surges for its 7500rpm red line. The Ferrari retaliates with an angrier, higher-pitched wail. Maranello’s V8 pushes 1000rpm deeper than the Alfa’s, the needle spinsfaster, the gears bang in superfast. I fire home third, the Alfa’s exhaust replies with a boom. Lift for a corner, pop, pop, pop. What fun. The Alfa has raw talent and always feels supercar rapid, but its ageing Maserati underpinnings let it down. The ride is unyielding, the steering quick to respond but slow to communicate, and the brakes lack pedal feel. All the while you’re aware of what feels like an incredibly short wheelbase and a limited slip differential – the component that felt so aggressive at low speeds – that’s too keen to pitch the car sideways. A wet corner taken too fast in third gear will spoil your day. So the 8C never leaves the Ferrari behind, but you sense that, on these twisting roads, even the Scuderia would struggle to build a lead if roles were reversed.

I climb into the Scuderia’s supportive seats. The textures are striking: the smooth carbon; the cold chequerplate flooring; the soft-touch alcantara. Spot the reassuringly chunky welds in the naked footwell, the yellowtachometer that dominates the instruments and the steering wheel mannetino with its five settings. Press the red starter button and the V8 fires. Accelerate hard, sense the huge grip, hear the note deepen beyond 3000rpm.

Oncoming headlights are visible from way down below, so our charge can be more intense. Maserati instantly slips into its own pace, the Ferrari and Alfa moving rapidly downhill and into the distance. Set the dampers to soft and the Scuderia chassis is see-through communicative, the steering responsive, the carbon ceramic brakes strong, if over-eager to trigger the anti-lock.

The Ferrari feels as quick as its 503bhp suggests. But the 450bhp Alfa is still in touch. Lights flash against craggy rock faces, sporadic bursts of battered armco narrow the road and amplify the pace. Look through the corner, not at what you’ll hit. Not at what you’ll hit! Can the object in my mirror really be closer than it appears?

Finally, we slow for an urban speed limit and pull over – hearts pounding, eyes wide open – and wait for the Maserati’s distant lights to join us. The contracting metal of hard-worked engines pings in the night air and the dry, acrid stench of cooked brake pads fills our nostrils. It’s been a long day. Tonight we head for Modena.

The road to Modena isn’t exactly dream-driving material. It’s mostly motorway, but that’s not all bad news. This first section of autostrada is actually supercar heaven. Here’s a slice of nirvana coming now, a long tarmac-floored cylinder cutting its way through the rock face that amplifies exhaust noise like a Marshall stack wired to the national grid. You know where this is going: tread the brakes, drop four gears and both windows, let the revs fall to around 3000rpm, take one last breath, tighten your grip on the wheel and steel yourself for the impending explosion. Thunk. The pedal hits the stop. Thwack. Your head hits the horse stitched into the seatback as all hell breaks loose. Do not lift. Do not lift. Just try to ignore the fact that the mechanical rave happening behind your head is scaring people in the next lane. Under pain of death do not lift until you’ve kissed 8600rpm on at least three occasions. Bottling out early is as unsatisfying as stifling a sneeze because you don’t get to experience the absurdly quick 60-millisecond gearchange. The Alfa’s paddleshift ’box feels as sophisticated as a three-speed crash-box in comparison.

And you really must take it all the way to eight-six to get the full effect of the ear-bleeding soundtrack. At low to medium speeds the Scuderia’s flat-plane crank engine sounds exactly that – flat, its exhaust simply loud rather than tuneful, its timbre more like that of a hardcore four-pot beside the retro V8 yowl of the other cars’ more conventional 90-degree V8s.

But wind it up until the last of the wheel-mounted shift lights have illuminated and it is utterly terrifying both in volume and tone. Intoxicating stuff, a bit like the litres of poisonous gasses you’ve gulped down as a result of driving for miles in tunnels with the windows cranked down.

You’ll risk bronchial pneumonia for the Alfa too, which bawls out bystanders like a deaf drill sergeant on start-up, and crackles on the overrun like logs on Beelzebub’s sitting room fire. This has to be the loudest production car on sale today. But, you know, it’s actually a little overdone. Fun for five minutes, but too droney at part throttle. And it writes cheques the engine can’t cash: this is a fast car but not that fast. Yet with 50bhp more than the Maserati and 390kg less weight to carry, it minces the refined-sounding Granturismo, for which brisk is a more appropriate word.

Eventually you pay for that tunnel tomfoolery with more than just your health. The autostrada’s regular toll stops, though great for drag racing your playboy companions from adjacent booths – Ferrari beats Alfa beats Maserati every time, in case you were wondering – are also a huge source of revenue for the Italian government. Though where the hell they spend that money is anyone’s guess. It certainly isn’t on this, the A10 motorway running along the north-western coast, which is one of the most ridiculous bits of tarmac in western Europe. No wonder the Italian road death rate is so high. Mostly unlit and devoid of cats’ eyes, it would be a strain to drive at night if it was arrow straight. But in places it’s twistier than an Alpine pass.

The body control of a racer and headlights that could pick up footprints on the moon are mandatory when even 70mph can feel terrifyingly fast. Approaching a corner without the headlights on full beam, there’s little indication as to which direction you might need to turn. Then, if you’re lucky, some chevrons might appear on the unyielding concrete walls. So you turn in. And there, right at your window is the crash barrier. Margin for error? What margin? Only the Ferrari’s pilot feels truly relaxed. I’ve switched to the Maserati and neither it nor the Alfa can calm the nerves.

Astonishingly, the Scuderia is just as useful when we leave the twists and tunnels behind. With the dampers set to soft, it is genuinely comfortable – much more so than the Alfa – and, even without carpets, it’s not the marbles-in-a-washing-machine experience you’d expect.

Here is a car that looks like it was built for Sunday use only (and I’m not talking about the drive to church). But it’s actually perfect for Monday through Friday too. The pathetic single-DIN radio/sat-nav is a disappointment – the Alfa’s is similarly old-tech – but the forward visibility is the best here and better than a Mondeo’s, while the nose’s cargo-hold swallows all of our luggage with ease.

But there’s only one car for this journey and, predictably, it’s the Maserati. The swept-back pillars create a terrible blind spot and the front chairs are oddly firm but there’s enough space in the back to make it a proper four-seater, the build quality is terrific, and it’s the only car with cruise control and full-screen navigation. Even so, we take the wrong road and end up driving north towards Milan. Realising our error, we turn off at the next junction to head back only to immediately re-take the wrong road, a procession of supercar ineptitude.

We stay at the inappropriately named Hotel Executive. It’s museum stuff, the décor reminding you of newsreels of Russia before the fall of communism. I don’t feel much like a playboy anymore. The Eastern Bloc feel continues as we crank the cars into action next morning. If, in your romantic view, everything in Italy looks like the Amalfi coast, I’m sorry to spoil things. The north is like Britain before decimalisation. You can buy wiper blades from petrol stations, but not coffee. From your window you see nothing but miles of featureless agricultural land and the unremitting greyness of ugly industrial units. But the great roads and beautiful scenery are there, they just take some uncovering. Central Modena is beautiful and, if you travel south from there, the flat, almost fen-like fields become lush rolling hills, and rod-straight roads start to flex in every direction like a free-form jazz tune.

We can’t resist one last thrash before it’s time to return the cars. The Ferrari is sensational. The steering is like the power reserve gauge on a Rolls but telegraphs remaining grip instead of torque. It’s the most responsive just off the straightahead, but not nervous. I’m mesmerised by the combination of electronic differential and electronic stability system. From the rain setting – with its zero tolerance attitude to lateral movement – to the on-your-own-mate CST-off, it does it all.

On these damp roads the 8C feels twitchy as you near the limit and the steering awkwardly heavy, but be brave, commit to a slide and it comes good, faithfully following the arc you mapped out in your head. The Granturismo’s far too refined for that sort of silliness. And a bit short on grunt. But that’s not what it’s about. It’s a proper GT, a Merc CL and Bentley Continental rival for people with fire left in their bellies and an eye for a bargain. It’s fun to drive but better to own: the nearest it will get to lapping Monza is the VIP car park on race day.

Like the Granturismo, the Ferrari is a multi-faceted machine, but one whose character is firmly skewed towards performance rather than luxury. If you want to immerse yourself in the mechanical process of driving, there is none finer. Which is why it’s so surprising to find it so usable – unlike the old Challenge Stradale.

And what of the 8C? It’s not perfect and, as all 500 are sold, you can’t even have one. But even if its connection to showroom Alfas is tenuous, be thankful it exists, and just pray that the next Brera coupé might be blessed with such beauty – but, please, not its ride quality.

For five days we lived in the company of these three descendants of those 1950 Monaco winners, but still only caught a glimpse of what it must be like to own these amazing cars. To those fortunate few expecting to take delivery of any one, we doff our caps as we set off for England on our Ryanair winged cattle truck. For us, the dream is definitely over, as distant a memory as that 1950 Grand Prix. For some though, it never ends.