► Gavin Green drives the Ferrari 288 GTO

► Epic drive from Maranello to London

► Wonderful CAR+ archive tale from July 1985

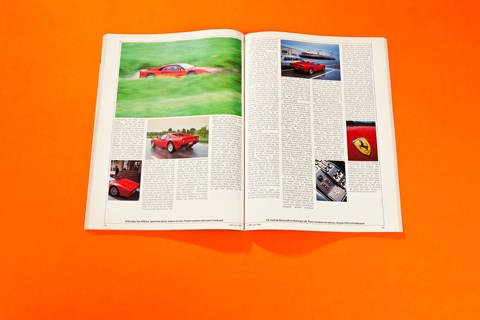

The tiny village of Grazzano Visconti in northern Italy will never be quite the same again. The red Ferrari GTO, on its first day out of the Maranello factory, drove slowly into town, its exhaust burble reverberating down the narrow streets and echoing through the houses and shops. Shutters were opened, and heads popped out. People ran out onto the streets. We pulled up in the main piazza, gave the engine a final blip, and then turned the key to extinguish the muscle of the most powerful road Ferrari of all. If Ronald Biggs rode down Fleet Street on Shergar, the look of surprise would not be any greater.

But then the amazement turned into one of mirth. G-T-O, G-T-O shouted a few of the locals. Ferrari, Ferrari, other voices yelled, accenting the ‘Rs’ heavily, and rolling the vowels through their mouths with the same vigour they were using to wave their arms. We – new owner Ron Stratton and I – got out of the car and were greeted like a couple of racing drivers who’d just stepped out of the winning car at Le Mans. Then we lost the Ferrari in a sea of enthusiastic youngsters, slightly more circumspect parents, curious old folk undaunted by the frenzy of the children and even three nuns – whose sombre black and white contrasted with the colour of the crowd.

The owner of the restaurant that bordered the piazza offered us wine, ‘or perhaps some other aperitif – with my compliments’, while some parents ran to get their pocket cameras to photograph their children with the Ferrari. Little Instamatics were clicking while parents entreated their children, standing bright-eyed in front of whatever corner of the car was free, to straighten their shirts and tidy their hair. Grazzano Visconti’s other tourist attractions – and it is a very pretty village, owned in its entirety by the late Italian film director Luchino Visconti – were ignored. Nothing could have usurped that Ferrari GTO that day. The new scarlet paintwork shone brightly in the Italian spring sun, and set off to perfection the lines of the most beautiful supercar of all.

The car even halted a wedding procession. Just as the happy couple were being chauffeur-driven from an old church, through piazza, the crowd of people caused the driver to stop his white Mercedes. So Mr and Mrs Newly-Weds got out of the bridal Benz and proceeded to pose in front of the GTO for their official photographer. The restaurant owner approached me again, as the bride and groom smiled radiantly in front of the car. ‘Now I know what you are doing here’, he said, eyes beaming and hands waving. ‘I have just heard. So this car is a present from the Visconti family to the happy couple!’

Eventually we had lunch in the village, before we took our Prancing Horse back outside the town, and directed it north on the next stage of our run back to London. The population of Grazzano Visconti – all 280 of them, or so it seemed – lined the road out of town and waved.

About the only place on our 1000-mile drive back from Maranello to London where the new GTO was not greeted with awe and incredulity was inside the Ferrari factory itself, where such sights are clearly quite common. Ron Stratton and I arrived at the hallowed green gates of the Maranello factory at about 2pm. Although Stratton – who runs one of Britain’s more progressive Ferrari dealers, Strattons of Wilmslow – is a Maranello veteran, it was my first visit to the most emotive name in motoring. We parked our Fiat Uno rental car alongside a brace of Lancia Themas in a small car park near the main gate, and went in to the bare reception area, where a group of hefty Rocky Marciano look-alikes questioned us from behind a thick glass security screen. When it became clear we had more love for Red Sports Cars than the Red Brigade they greeted us with big smiles and asked us to wait a few minutes.

As anyone who deals regularly with Italian companies knows, ‘a few moments’ can mean anything from a couple of minutes to some time next year but in this case Ferrari was to show Daimler-Benz-like efficiency. Stratton, complete with personal banker’s draft for £59,690 (‘that includes air-conditioning and power windows, which are a £250 extra’) was quickly relieved of his money and quickly escorted through a large showroom – complete with the ex-Rene Arnoux Formula One racer and another GTO – to a garage out back. And there, parked behind a red Testarossa, was the car.

It did look magnificent. A mechanic was adjusting the tyre pressures of the huge Goodyear NCT rubber – 225/50VR16s at the front, 255/50VR16s at the rear – while the Ferrari man gave Stratton a quick run down on the car. One thing soon became obvious: the election of tapes Stratton had brought with him on that morning’s British Airways flight from London would be useless, for an unsightly rectangle of plastic occupied the space where Ron expected to find a radio. ‘A radio cassette player is an option’, explained the Ferrari man. ‘Although we do fit the speakers and the wiring as standard.’ ‘What do you expect for your 60 grand?’ replied Stratton, half serious.

But the man was genuinely excited and pleased, and who could blame him as he clambered down into the low seating position for the first time, and felt that lovely three-spoke Momo steering wheel and looked over that comprehensive cluster of instruments. From the outside, the car is even more impressive – with its vast wheelarch flares housing those huge tyres, extra scoops and slats compared with the 308GTB, and yet with the same rounded poetic lines as the lovely GTB. Not that you’d ever get the two cars confused. The GTO, which has totally different panels from the GTB apart from the same aluminium doors, looks far more muscular. Alongside, the GTB is a Dinky Toy. As we drove across Europe, few people mistook the GTO for a lesser Ferrari. The size of Stratton’s cheque was further testimony to their differences.

Ferrari had made only 200 customer GTOs. Built ostensibly as a Group B raining sports car – 200 is the minimum number needed for homologation – but bought more commonly as road machine and as gilt-edge investments, the GTO is probably the fastest road car Ferrari has ever built. Far more of a practical street machine than any racing Ferrari sports car of the past – it has a fairly luxurious interior, and is a very easy car to drive in traffic, as our run back to London would demonstrate – the GTO is already regarded as one of the all-time classic Ferraris. Thanks partly to its limited volume, it’s one of the most valuable, too. Stratton’s machine probably doubled in value before he even saw it.

Not only is the car one of Ferrari’s most valuable, it is one of its most technically interesting. It is the first Ferrari road machine to make extensive use of plastic composites, and the first high-performance road Ferrari to use a turbocharged engine. The body is made of glassfibre composite with the exception of the doors. The rear bonnet and rear bulkhead are made of a Kevlar composite. Despite being longer and wider than the GTB, and despite having heavier mechanicals, the GTO is 250lb lighter. The lightweight plastics technology is the work, mainly, of British engineer Doctor Harvey Postlethwaite. Other Ferrari road cars will increasingly use plastic body bits instead of steel.

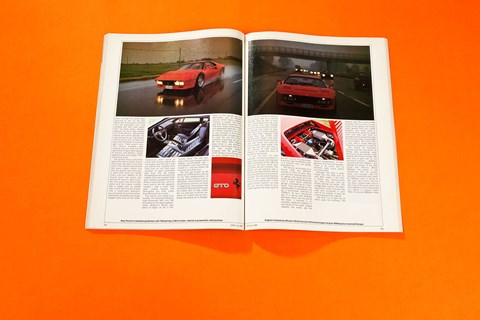

The engine is based on the 3.0-litre quattrovalvole V8 used in the 308GTB and Mondial, but much modified. In order to make the GTO qualify for Group B racing, the capacity is reduced to 2855cc (when you multiply the engine capacity by the constant of 1.4, which is applicable to turbo engines, you can see that the GTO just sneaks in below the 4.0-litre class limit). The engine is also turned 90deg compared with the GTB unit, so that it is placed longitudinally. The five-speed gearbox is in-line behind the engine, in the best racing car fashion. As a result there is no rear boot in the GTO. Stratton warned me to pack lightly for the trip.

The all-alloy V8 is placed well forward in the engine bay, with the front four cylinders hidden under the rear scuttle. At the back of the bay are the twin Japanese-made IHI turbochargers – one for each banks of four cylinders – which are largely responsible for the GTO’s 400bhp power output and the massive 366Ib ft of torque.

After our brief introduction to Ron’s new rocket, we were asked to go back in the showroom, ‘while we fit the number plates of the car’. Ten minutes later, with the perpetual cigarette still between the centre and index finger, the Ferrari executive returned to tell us, ‘Your car is ready’. It was out of the garage now, parked only 10ft from the electric gate of the Maranello factory. Stratton was handed the keys, given a Prancing Horse key ring ‘with our compliments’ and was told about there being a box full of spares in the front boot. He shook hands with the thick-set Ferrari man and then climbed down through the narrow door opening to rest on the thin Boxer-like driving seat. I climbed into the passenger side and bumped the rear-view mirror with my head. Stratton gripped the thick little leather rim of the Momo. ‘Where’s the electric door mirror adjuster’, he said, eyeing the two big exterior mirrors which stick up from the doors like the heads of oversized golf clubs. The electric windows were lowered and rain spat onto the upholstery. Fingers were applied to mirrors until Stratton, clearly apprehensive, was happy. Time to go.

The ignition key is just to the right of the Momo wheel. Turn it and some red lights jump into action. Then Stratton pushed the little black starter button just near the ignition key, there was a brief whirr from the starter motor and then 400bhp of V8 muscle burst into action just behind the driver’s right shoulder. One quick stab of the right pedal and the engine snarled like a caged wildcat poked with a stick. Not that the engine note is particularly obtrusive: you can certainly hear those four camshafts, those 32 valves and those cogged belts play their tune inside that engine-bay auditorium. But the engine, even though it rests just behind the carpeted bulkhead only an inch or so from your shoulder, is never uncomfortably loud. The tall plastic-knobbed gearleaver stands in the middle of the six-fingered metal gate. Stratton grabbed the knob firmly. It went into first – which is back, and to the left, opposite reverse – with a clunk. First gear proved stiff throughout our mille miglia from Maranello to London.

The barrier was raised and, outside, the Maranello-Modena road beckoned. With only 193 kilometres on the Veglia speedometer, Stratton’s Ferrari was about to begin its life in the outside world. The stiff twinplate clutch was engaged with a slightly uncomfortable jerk – both Stratton and I took time to master it – and the Ferrari left its home, bound for ours.

The rain got heavier as we drove out of Maranello, and out of our first conglomeration of waving, screaming fans. Even in Maranello, where Ferraris must be as common as Fords in Dagenham, they looked hard at the GTO. We travelled through the flattest part of Italy, where the sun-parched buildings rise above the verdant spring landscape like wooden blocks on a snooker table, to the equally flat and featureless city of Modena around which Italy’s supercar industry is based. The traffic was bad. Eventually we got to the Fini Hotel, after stopping three times to ask directions. Stratton, who’d been driving all the way, looked relieved. Gingerly, with the gruff bark of the V8 bouncing through the car park, Stratton took his car down into the bowels of the Fini and parked next to a normal 308 GTB. After he left, a thick grille descended over the exit. The Ferrari man had insisted that the car should be in a lock-up garage that night. In Italy, they don’t only revere Ferrari’s, they steal them. Stratton had heard that two GTOs had already been stolen, one from Paris. So we left the car and ate well and drank well and, for some reason, slept badly. The next day was fine with only a thin shroud of mist to hinder the burn of the Italian spring sun.

It was my turn on that Saturday. The driving position is good, even though your legs are offset noticeably to the right to clear the left front wheelarch (all GTOs are left-hookers). The pedals are well placed, with a generously sized left footrest to brace yourself when the g-forces get high. The little black steering wheel is set more horizontally than in most sports cars – in the typical Italian fashion, so that you can rest the heels of your hands against the lower part of the rim – and is not adjustable. It was too high for Stratton, who is a smallish man, but ideal for me.

Although the GTO is 2.4in longer than the GTB, and almost 8.0in wider, it still feels a wieldy and manoeuvrable car when first you take up station behind the wheel. The cockpit feels narrow; the steering wheel is small; and you feel cosy and contained in your half of the cabin.

Not that it is a light car to drive; quite the contrary. The steering, with 10in of low-profile Goodyear NCTs to muscle around, is very heavy at low speed, and rather lower geared than you might imagine. You really need a strong hand to guide the gearlever into first, and then a positive hand to guide it through the other four cogs, all arranged in an H-pattern. The clutch, too, is firm, with a sharp take-up. Practice is needed to master it.

The frenzy of Grazzano Visconti and the flat plains of Emilia and Lombardy were behind us, as we headed north towards the French border. We were still in part one of our running-in routine – 4500rpm maximum for the first 1000km – but already the power of the Red Horse was obvious. Below 3000rpm, the power is not exceptional. The car accelerates, sure enough, and has excellent tractability right down to 1000rpm, even if you’re in fifth gear. But there’s not the low-down, torque-laden kick in the small of the back which the Ferrari Boxer and the Testarossa can deliver in copious quantities. At around 2000rpm, when accelerating, the little turbo gauge – black, with orange markings like the rest of the instruments – moves off its stopper, and there’s a noticeable helping hand from the twin puffers, already whistling quite audibly. Strong momentum is being gained, but there’s still no power explosion. Wait until around 3000rpm for that. Sure enough, as the thick orange needle continues its swift sweep of the rev counter and passes the 3000 mark, the turbo gauge jumps to 0.8 bar – maximum boost – and the previous distant whistle of the blowers and grumble of the engine is replaced by a blood-curdling howl. The helping hand turns into a full-blooded right jab, and the GTO bolts forward with more ferocity and fire than any road-going supercar in my experience. The effect as the blowers come in, can most accurately be likened to that of a Porsche 911 Turbo when the boost becomes strong. But the power jump is more savage. It’s as though you’re in a glider, in tow behind an innocent prop plane, and the tow rope suddenly becomes intercepted by a low-flying F-111. And so quickly does the crankshaft accelerate when it is aided by full boost from those twin IHI blowers that, if you want to keep full acceleration, you need to swap cogs very quickly to avoid over-revving. It takes practice, too, to swap cogs fast enough and cleanly enough to allow the car to surge on in one uninterrupted blast, rather than in five disjointed ones. The 1-2 change is the one most likely to cause trouble, particularly in a new car with stiff linkages. The other lever movements are more fluid. With practice, and without any running-in restrictions, Ferrari says the GTO can accelerate from 0-60mph in under 4.9sec, can cover the standing quarter mile in 12.7 sec and won’t stop accelerating until 189.5mph. Drive the car and you’ll believe the figures.

Not quite as impressive as the car’s open-road performance, but somewhat more surprising, is the GTO’s ability in town. The sheer tractability of the machine – particularly for a turbo racer – is amazing. In Modena and then in London two days later, the car was capable of trundling around town, dicing with Fiat 500s and Minis without changing out of third gear. The vision out of the car, although not of Fiat Panda proportions, is not bad for a mid-engined racer either.

Our view out of the windscreen, however, became far more scenic as we left the last of the Italian autostradas and headed north onto the roof of Europe. Ahead, hiding in a sheet of mist, lay the outline of the most spectacular mountains Europe has to offer. We kept climbing, as we drove through Aosta, heading towards the Mont Blanc tunnel. The mountains become clearer, sharper, and the drops in the valley became greater. Snow covered the tops of the mountains like pointed white hoods, and trees clung tenaciously to the sides of the hills, temporarily free of the heavy snow with which they had been encumbered only a month earlier. The road wound higher and higher. We passed a few lorries, labouring like old men up a steep flight of stairs, breathing heavily with the exertion. The Italian border guards were playing cards and paid us no attention. So were the French. So we passed through the Mont Blanc tunnel and heard the Ferrari’s melodious engine note change as it reverberated back off the tunnel walls. If the fumes hadn’t been so bad, we would have wound down the windows better to savour the sound of the Ferrari V8.

We drove through Chamonix and other names better associated with white slopes than red card, and kept well clear of the spring snow which still clung a foot deep to the roadside. We crossed briefly into Switzerland before reaching the tranquil shores of Lake Geneva, encircled by tall mountains like broad white-haired giants standing around a pond. Millionaires’ homes, impressive but inconsequential compared with the rest of scenery, fought for space on the lake’s shore. In Evian, just over the French border, the Hotel de la Verniaz, with a panoramic view of Lake Geneva, housed us and fed us as only good French eating houses can.

It was raining again on Sunday. Clouds hid the peaks of the mountains and raindrops pricked the surface of the lake.

By this stage we had got our packing routine down to a fine art: Stratton’s leather bag – a made-for-Ferrari device, with a GTO motif – could be insinuated in the front boot with some judicious packing, while my bag – and all our oddments – were kept on the passenger’s floor, hard up against the seat cushion. We were comfortable, if a little cramped.

We crossed back into Switzerland, drove around the east side of the lake to Montreux, and then joined the autoroute, bypassing Lausanne, before heading north-west on back roads to the French border. Just outside Lausanne we passed the 1000km mark; we could now use 5500rpm. To celebrate we gave the car a quick burst up to 140mph, about our rev limit in fifth. The GTO was still incredibly stable and, although the engine produced a definite growl, conversation between driver and passenger was still possible. Later, with more miles behind us, we tempted the GTO even higher up its performance tree: to 155mph. It was still so simple and so easy to drive, that to laud that velocity as a driving feat would be totally to underestimate the excellence of the machine. Vigilance was necessary, but not skill. Mostly, though, we cruised at between 90-110mph. At 110 the Ferrari is mechanically quiet, with only some wind gush and occasional tyre road spoiling the tranquillity.

Back in Dover, after an excellent overnight stay in Le Chateau de Ligny, in Ligny-en-Cis near Lille, the special nature of our steed was immediately recognised by the surprisingly friendly man from Customs and Excise. ‘This one of the 200, is it?’, he asked Stratton, just before he asked him for a cheque for £14,668.45 – which took the total cost of the GTO to £74,358.45. Stratton handed over the cheque with more glee than I have ever seen in any man handing money over to the government. ‘I just wanted to get it over with quickly’.

Now, of course, the Ferrari GTO had gone – it lives a couple of hundred miles away from me, in Stratton’s showroom in the main street of Wilmslow and I am left with memories and a notepad full of scrawl. But the car is still so clear, and so fresh in my mind. I can still feel the surge of acceleration over 3000, and the excellent cruising performance. I remember taking a series of bends in France at well over 110mph – bends that most cars would be struggling to conquer at 60. I remember my surprise at working out the car’s fuel economy figures – a worst of 19.8mg, a best of 21.9, both excellent figures. I can remember the very firm ride which, on some French D-roads and even one section of poorly surfaced autoroute, made the car jerk and bob and the huge four tyres in concert with the stiff springs and dampers, fought an uneven struggle to conquer the bumps. On a concrete part of the M2, from Dover to London, the tyre noise and the regular thump of the joining strips prompted Stratton to liken his Ferrari to the Manchester to London train. I remember the minimally damped steering, which caused the wheel to wriggle and writhe in my palms as the front tyres climbed over bumps and into holes. Brake hard and the front wheels would always point the same way as the road’s camber. I remember the growl of the engine on full throttle, the cramped cockpit and the poor ventilation which, in conjunction with the steeply raked screen, made the optional air-conditioning a must.

I remember my last sight of the GTO, when Stratton dropped me off in north London on a wet and miserable Monday. It growled off down the High Street, a prince among all the pawns.

In Retrospect

The fact that the GTO was conceived as a Group B racer and the initial run of 200 road cars (272 were eventually built) was to satisfy homologation, is now all but forgotten. So is the fact that the GTO broke the mould by extensive use of plastic composites. And the performance, although ferocious, has long been overshadowed by that of the F40.

No, the GTO is celebrated for being the most achingly beautiful of all supercars, combine that with 190mph performance and exclusivity. What other car could have worn the GTO badge and not suffered by comparison with the ‘60s icon?