► CAR visited the 2019 festival

► Celebrating the very ordinary

► Next festival is in 2021

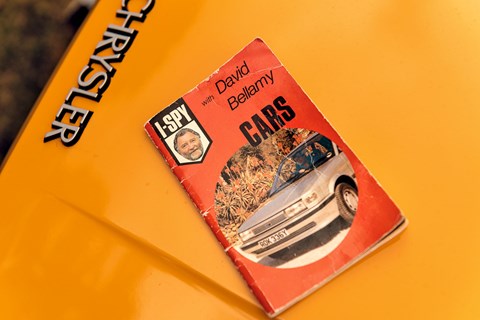

Today I woke at 5am and abandoned my kids, driving four hours to stand in somebody’s front garden and gawp at a 1988 Nissan Sunny 1.6 LX. I love cars but this is ridiculous. It’s all David Bellamy’s fault.

The recently deceased bearded botanist was all over TV in the ’80s and ’90s before some rather un-zeitgeisty views about climate change led to him being excommunicated by the Beeb and his other employers.

And for a time in the early ’80s, one of Bellamy’s employers was Ravette, then owners of the I-Spy books series. First published in 1948 by former headmaster Charles Warrell, these books were designed to keep post-war kids entertained on boring journeys when iPads were the kind of witchcraft you read about in the Dan Dare comic – the comic you’d finish in the first hour of the trip and discard on the floor of your dad’s Ford Popular.

There were different I-Spy books covering different themes, and thank God I ended up with the cars book and not the one about British coins or supermarkets. The cover of my 1983 I-Spy Cars features big Dave and the front end of a then-new Austin Maestro, while on the back there’s Lagonda designer William Towns’ weird six-wheel Hustler, the result of three Mini subframes crashing into a conservatory showroom.

Inside the book, cars are arranged by the name of the manufacturer in alphabetical order, with a space below each for you to record the registration plate to prove your find. I wonder how many kids cheated. Some entries require you to spy a specific model, like a 300-series Volvo. For the more rare-groove marques, like Porsche, any model will do. Once you’d finished your book you’d send it away to Big Chief I-Spy, who’d stamp and sign it before sending it back.

Unfortunately, though the scrawl under cars like the Talbot Samba, Ford Granada and Volkswagen Passat testifies to my attempts to make that happen in the early ’80s, I never did finish it.

But for some reason I hung on to the book, occasionally toying with the idea of finishing it, even plugging in a couple of magazine test-car plates for Morgan, Ferrari and Bentley as I’d driven them over the years, then immediately feeling guilty that they weren’t period correct, so didn’t count. No, if I was going to complete the book and get Bellamy’s approval it had to be with cars I could have spotted in, or at least close to, 1983.

But how? The irony is that the cars that were so difficult to spot in ’80s Newcastle – the Ferraris, Aston Martins and Bentleys – are the ones that are relatively easy to spot today. First, because they’re now built in greater numbers than they were 35 years ago (Aston built 30 cars in 1982; 6441 last year). But also because so many of the older cars have been preserved.

No, it’s the ordinary cars, the cars that once littered every street, that would have been an easy spy back then, that are the hardest to find today. Cars churned out in the millions that are now almost impossible to find.

I used the DVLA’s website to check the VED status of the 34 cars whose plates I’d recorded in period. Some didn’t even see out the ’80s, and only a couple made it to the new millennium. Only one, a Mercedes SL380, registration JYU 961W, is still listed as taxed and MoT’d.

Thirty-one entries remain blank. I might take years to tick them off, if I ever manage it. Tracking down a Renault Fuego (18 taxed, according to howmanyleft.co.uk) was going to be tough enough. But where on earth was I going to find a bloody Talbot Rancho?

And then I heard about the Festival of the Unexceptional, which is how I find myself standing on the front garden of Claydon House in Buckinghamshire, watching a man wearing an IWC chronograph lean gingerly over a long bonnet – heaven forbid he should damage its pristine, original paint – to get a better look at a car worth considerably less than his watch. ‘Total left in UK: 2’ reads the sign in the window.

In one sense, it’s a familiar scene. Dozens of the world’s rarest cars, paint and chrome gleaming under the British summer sun, parked for all to admire on a pristine lawn in front of a posh country pile.

But this isn’t Goodwood and you won’t find any 250 GTOs or Porsche 917s here. This is an anti-Goodwood celebrating the car your Uncle Gordon might have driven. Rover 200s, Mk1 Clios, Austin Maestros, Mk5 Cortinas, Vauxhall Carltons, Yugo 45s. Cars that you took for granted because they were everywhere, until they weren’t. Cars whose attrition rate makes the Great War’s seem inconsequential. When did you last see a Datsun 140J? Or a Renault 6? Or a Toyota Carina II?

The centrepiece of the one-day event is the Concours de l’Ordinaire, which involves a panel of classic car expert judges picking a winner from 50 perfectly preserved but almost universally undesirable cars from that weird hinterland between used car and classic. It’s like watching Quincy Jones and Calvin Harris arguing over whether Brother Beyond or 5ive should be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

‘We used to get organisations like Salon Privé trying to persuade us to get involved,’ explains Marcus Atkinson from Hagerty, the classic car insurance broker behind the show, now in its sixth year. ‘But the sums involved were huge and behind the scenes we were starting to wonder why there wasn’t a space in the classic scene for ordinary cars.’

And by God, are they ordinary. Not all of them, mind. The kitsch 1973 Toyota Crown Custom estate with the striking blue interior is far too cool to be considered unexceptional. But mostly they’re deathly dull, or ought to be. Instead, they’re strangely fascinating.

Almost all in plain, non-sporty spec, often wearing wheel trims and un-sexy non-metallic paint. Almost all with the same backstory – owned by an old boy who bought it after he retired and barely used it. Almost all now owned by someone who can pin their peculiar fascination on dad having once owned one, or sold them for a living. And each one representing a model only a handful of MoT failures from extinction.

Some of the cars are, quite literally, unrepeatable.

Case in point: a 1978 Chrysler Horizon, never registered and displaying a genuine 300 miles on the clock from its one journey across the sea from Ireland to Bristol wearing a set of fake plates borrowed from the owner’s other Horizon.

Seeing is disbelieving. If we were talking about an air-cooled 911, or even a boggo Mk2 two-door Escort, collectors would be falling over themselves to throw money at the owner so they could put it in their living room. ‘It’s probably only worth £4k,’ says its owner.

Money, or more precisely the lack of attempts to part you from it, is one of the show’s most refreshing aspects. Obviously it’s run by an insurance company who’d love your business, but you’re not bombarded with branding or attempts by car manufacturers to hijack it, or by branding from Hagerty or any other sponsor (though judging by the amount of filler in the arches of some of the cars out in the main car park, Isopon would be absolutely on-brand). But the real brilliance of the Festival of the Unexceptional is its inclusivity. Yes, the Goodwood Festival of Speed gives us a chance to see and hear many extremely rare and important cars. Standing next to the plane-engined Fiat Mephistopheles or an Auto Union as it cranks into life is an incredible experience, but unless you’re a motorsport buff you’re unlikely to feel much of an emotional bond to any of them.

At the Festival of the Unexceptional, it’s a different story. Because the cars here are so ordinary, and drawn from such a broad period stretching from the ’60s to the ’90s, everyone can relate to them. If it wasn’t your first car or your dad didn’t have one, your teacher, your driving instructor or the bloke two streets over probably did. As with Goodwood, the metal in the car park is as interesting as the machinery headlining the show. I keep coming back to the Mitsubishi Cordia Turbo with its twin gearsticks, and the Mk2 Vauxhall Cavalier Calibre whose awful Irmscher bodykit is so heavy handed it looks like it was designed solely to help smuggle vast quantities of Class A drugs across international borders, French Connection-style. And I can’t get enough of the Lancia Gamma and Alfa 2300.

Listening to snippets of chatter floating through the air you realise that the people here are every bit as knowledgeable about these cars as the Porsche and Bizzarrini geeks are at Goodwood. ‘Ah yes, but that upholstery/gearbox/wheel trim was only used between ’79 and ’80,’ they say.

I spot former CAR editor Richard Bremner imparting his vast BL knowledge, and then bump into another ex-CAR ed, Steve Cropley, who’s here with several senior figures from the UK car industry. Between them they’ve brought a load of cars from the Vauxhall and Mercedes heritage fleets. Not so they can press the corporate message. But because it seemed like a great day out. The smiles on their faces say it is.

And despite the larger field containing everything from a Ferrari 412 to one of those pale blue Invicar mobility trikes, everyone seems to respect Hagerty’s ‘no sneering’ policy.

A sheet of paper in the window of a lovely J-plate Citroën BX GTI automatic sums the spirit up best. At the bottom of the page beyond the car’s description, it reads: ‘I also own a 2CV and a range of other cars from an Aston Martin to a Porsche 911 and BMW i8. I love this car, though.’

This main parking area is a great place to look for opportunities to fill the blanks in my book. I spot a TVR 350i (the I-Spy pic is of a similar-looking but less-powerful Tasmin, but the text says any TVR is allowed) and replace the modern Ferrari entry I stuck in a couple of years ago with a relatively period-correct Ferrari 412 (the book shows a slightly earlier 400i).

But then I start to get picky. I need a Fiat Panda, and get all giddy when I see one across the car park, but my hopes are dashed when it turns out to be a foreign-spec 34-badged model. I can only score for a Super or Comfort. There’s more hand-wringing over a Mk3 Supra. The book shows a Mk2, so I pass. Still, by the end of the show I’ve ticked off several missing cars, including the Peugeot 305 SR that won the People’s Choice Award. In the low-octane concours shootout a spectacularly unpleasant Morris Marina estate that was rescued from the crusher pipped a Vauxhall Chevette to take the overall win. Edge-of-the-vinyl-seat stuff.

No sign of a Talbot Rancho, sadly, so my book remains incomplete. And in any case, with David Bellamy now tending the great greenhouse in the sky, I’m too late to get his thumbs-up. But it’s an itch I need to scratch, and with only two Ranchos on the road, I’d better get a move on before they fail their final MoT.

If I’m going to finish the job, this is the place.

Want a visit? The next Festival of the Unexceptional is planned for July 2021.