► Ferrari to the end of the world

► Bremner drives 3000 miles in a 550

► A CAR magazine archive gem from 1999

Most would go to the ends of the earth for a Ferrari, and we’re no exception. In Buenos Aires, we pointed the nose of a £150,000 Maranello at Tierra del Fuegos, more than 3000 miles due south. And hit the gas.

There’s nothing we can do now. The Ferrari heaves from side to side with increasing violence as gouts of water splash across its bonnet. The horizon tilts crazily and I begin to feel a little sick, while remembering that to escape a sinking car you must allow it to fill with water before attempting to get out – otherwise you won’t be able to open the doors. And that will mean a long wait in cold water. Very cold water.

We – that is, myself and photographer Anton Watts – are sitting inside a Ferrari that’s aboard the tiny ferry shipping trucks and cars across the Magellan Straits, from the Argentinian mainland to the Isla Grande in Terra Del Fuego. Ripping winds are scuffing the sea’s surface, turning it from blue to white, and forcing the ferry – we can’t help noticing while we wait to board to aim for a point on the shore well to the west of its actual landing point. The idea seems to be that, as it slows down to dock, the winds will do the rest. Then we just have to drive down the ramp, dunking the 550 Maranello’s wheels into the chilling straits for a moment, before mounting the ferry itself. Simple, really. The fact that we have seen trucks half-on and half-off the ferry while it bucks about in the wind worries us less, perhaps, than it probably should. But we have a long day’s drive ahead of us (somewhat longer than we’d planned, it turns out), plunging further south than either of us has ever been before, and we’re quite keen to proceed. Because we’re going to the end of the world. By Ferrari.

You may well wonder why. At one point during the trip, so did we. Well, four years ago, this magazine took a Ferrari F512M to the Sahara Desert (CAR May 1995) – partly to exploit Morocco’s fabulous roads, partly to blow the ‘Ferrari’s are fragile’ myth, and partly because it was there. That last reason is the important clue: it’s so easy to apply to a range of interesting places. Like, say, Argentina. It’s undeniably there. Crucial premise satisfied, we formed a plan to drive a Ferrari to Tierra del Fuego – specifically, a place called the End of the World. To ice the rationale cake, it’s about as far south as you can get in a car without taking a boat to Cape Horn – and allegedly further south than any Ferrari has been. Which is how Watts and I came to be driving the silver Ferrari 550 Maranello to a press conference in Buenos Aires on April morning. All of Argentina wanted to hear about such meticulously-reasoned madness.

One route takes us south through the Pampas, west towards the Andes and the Lake District, south through Patagonia and on to Tierra del Fuego. It is the proverbial Long Way. The 550 Maranello, shipped from Italy for the drive, has 11,234 kilometres on the clock when we pick it up in Buenos Aires, and I needlessly add to the tally by getting lost shortly afterwards. But soon we’re plunging towards the Pampas, when a drenching rain sets in, caking the roads – and anything that goes near them – in grey mud. After just two hours, the 550 looks as if it’s been to Tierra del Fuego already. It must make a striking sight, for plenty of people stare. The nearest thing here to a supercar is a Renault Fuego – though there seems little confusion between the two – while assorted, ancient Ford Falcons, VW-badged Hillman Avengers, VW and Palios, Corsas and Renault 12s are nothing like it at all. But most people seem to know that it’s a Ferrari – you can see them mouthing the word.

It takes a while to leave the outer suburbs of Buenos Aires, not surprising with a city of 10 million. Eventually the buildings disappear and we’re rolling through flat, green-grey countryside, populated only with distant, dark smudges, that turn out to be Argentinian beef in its ‘before’ condition. The road is smooth, straight and endless.

Despite the rain, it’s possible to mount brief forays to 150mph – it’s just so easy in this car – until we decide, after a moment of aquaplaning, that something closer to 80mph is wiser.

The rain sheets down through the day, and the scenery – by some way the most astonishing thing is how unchanging it is – remains flat, green and grey, until we reach the outskirts of Bahia Blanca: a biggish port well south Buenos Aires.

The respite is brief, because when we leave there’s more rain. But 75 miles south or so, we notice a change in the topography – there are sudden outburst of brown-orange rock among the green, and amazingly, the rain is subsiding. It’s not as flat any more, either. Instead, we’re driving through a succession of shallow valleys, and more often than not, the road fades into the distance – completely undisturbed by curves.

Something is becoming increasingly hard to resist, and it involves the right foot. We realise that we can see clear road for three or four miles ahead.

Temptation beckons, and we’re in the perfect car to indulge it. Gathering speed in the 550 is so easy. You can leave it in sixth at 100mph, squeeze the throttle, not necessarily to the floor, and it will gather momentum with sufficient conviction to have you concentrating hard in short order. Not because it feels unstable – the reverse is true – but because the white lines, which we decided to straddle for safety, are narrowing under the 550 in a near-continuous blur. And, suddenly, the speedometer has arrived at 280kph, the 550 still accelerating firmly. That’s an indicated 174mph, and quite enough for now, thank you. The security it offers at these speeds is amazing. Slow to 100mph, and it feels like 30mph. Really.

Soon we stop for lunch, wait for the Fiat Ducato and Fiat Marea back-up vehicles, and snack on ham-and-cheese sandwiches. Later, we stop for Watt’s camera to take in a vista. I kick around in the dust – and hear a few gunshots. About five minutes later a black VW Santana drives by, three blokes aboard, one of them casually waving an item of light artillery from the front passenger window. It’s an eye-widening sight, though not uncommon, apparently, as the many, bullet-riddled road signs silently testify.

The last part of our journey that day involves some off-roading. We are heading to San Martin de los Andes which, as the name suggests, lies in the foothills of those famous mountains. Some of the way is dirt road, and the Ferrari feels perfectly stable – 479bhp or not – but the jolting and jarring is enough to make you wince. I try to forget that this car costs £149,701, as stones rattle in its wheel-arches and we bathe it in mud, but it’s not easy. Eventually we strike tarmac again, and indulge the Ferrari’s muscle over a swooping road that speeds us to San Martin. I discover that if you run the V12 out to 7400rpm – something it’s amazingly willing to do – the gearing allows you to accelerate almost seamlessly to crazy speeds, the engine pulling hard immediately after every upshift. And the 550’s grip allows you to enjoy it. The lack of roll and directness of the steering help too, so that it’s not long before you find yourself cornering, relaxed, at speeds topping 100mph.

So, it’s a salutary thing to have to confess to striking a dog a glancing blow, ironically while travelling far slower, which sends it to its maker – mercifully in an instant. My conscience, and Argentina’s fauna population, is further battered when I hit a hare that runs out, in the dark, a day or two later. It’s enough to earn me the nickname ‘killer’ from my fellow traveller.

The following mornign we clean the car, and ex-Formula-One engineer Raffaelle Brugnoli decides to raise the 550’s ride height by 155mm at the front, because the plastic undertray has already been damaged by the dirt roads. It will give a little more clearance, he says, but also introduce some understeer. He’s not wrong, though it takes quite some miles to notice that, at high speeds, the Maranello is definitely a shade lazier to respond to the wheel. It’s a small price for protecting its sump, especially as we are off-roading again, this time to Bariloche, which will take us past some of the most beautiful lakes in the world – imagine a more verdant version of Britain’s Lake District. Sadly, many of the roads here have turned to washboard – something the 550 does not like.

There’s a theory, popular in African countries, that if you drive fast enough, a car will float over pounding ridges, allowing the ride to smooth out. So we try it, teeth gritted as the jolting intensifies until we hit 60mph – and then, yes, the ride does smooth off. Slightly. Noise doesn’t abate, though, and we could hit a deeper rut at speed.

Sheer beauty has us stopping a while later, for lunch (on more ham-and-cheese sandwiches) near a farm whose 10 occupants, plus their assorted cows, horses, pugs and chickens, will be snowed in for winter, completely cut off from the outside world. From here, we advance through the hills, then trace the shoreline of Lago Nahuel Huapi. Can you remember the opening scenes of The Italian Job, in which that orange Lamborghini Miura is seen spearing through the Alps on a brilliantly sunny day? Well, this road reminds us of that, though I’m pleased to say that there’s no heavy-duty digger to greet us in the tunnel.

We go hard for mile after mile, learning how to set the 550 up for corners (resisting flurries of late braking seems to help its fluency), and discovering that switching the dampers to the sport setting limits roll noticeably and makes the Ferrari even tidier to hustle. In short order we arrive at Bariloche, to see kids goggle when they spot the car.

We are told that from here to our next stop at El Bolson, there are hard roads ahead. Indeed, mountains capped with stalagmite-like spikes confront us in the distance – the scene conjuring on other world atmosphere right out of The Hobbit. And El Bolson is populated by people who have occupied other worlds of different kinds – chemical other worlds. It was invaded by hippies back in the ‘60s, and plenty of them still live there. Just outside the town we notice strange, fat streamers of could hanging in the valleys, and we haven’t been anywhere near a hallucinogen.

When we get there, the place seems conventional enough. We stop at a roadside café to have a lunch that is not a ham-and-cheese sandwich (though it will be a few more days before we realise what a miracle it is), and meet the sizeable Miguel, who has seen the Ferrari outside. He invites us to one of the three garages he owns, for a coffee. He jumps into a VW Gol (not his, as it turns out – he ‘accidentally’ gets into the wrong one) and we follow him at high speed through the township to his well-equipped garage, where there are already plenty of people milling about. When they see the Ferrari, they surround it in open-mouthed and friendly wonderment. While we drink some (particularly fine) coffee, we meet Adrian, who is astonished. He was reading a story in the local newspaper (La Manana) about a couple of nutters driving to Tierra Del Fuego, when he looked out of the window and saw the car in the metal. Ooh, the power of the press.

We leave in front of a crowd, which makes it impossible to resist switching off the 550’s traction control, and using up a bit of one of our sponsor’s budgets by spinning the Pirellis in a modest power slide. We can hear the cheers over the engine as the Ferrari rockets away. Childish, yes, but what fun.

Not far south of El Bolson, the scenery suddenly changes. There are no trees at all, and not much habitable land. It’s utterly bereft of people, too, though after a while I realise that there are dozens of sheep – they look so similar to the ubiquitous scrubby bushes that they’re almost invisible. Eventually, we find some landscape variety again, coming across the brilliant-blue Lake Sarmiento in the middle of nowhere, and surreal herds of the gently nodding, pterodactyl-like oil pumps that extract Argentina’s petroleum, which in the south of the country costs half what it does in the north-good news when you’re in a 16mpg supercar.

Onward, and at one point we drive the Ferrari down a dirt road, skirting snow-capped mountains, dazzling lakes, crazily driven Renault minibuses and at one point, a horse. This animal, as magnificent as the cavallino rampante of the Ferrari’s badge, has run a well-worn path beside the fence of its enormous field chasing tourists’ wheels, and the sight of it bounding along beside the Maranello is a spine-tingling moment.

So is what comes next. In places, the dirt turns as smooth as mousse, and we turn the traction control – off we can’t help ourselves. I’ve never had a £150,000 supercar in a four-wheel drift on a dirt road before, and probably never will again, but the more we do it, the more it seems that the 550 is born for it. It arcs through curves with the grace of a skater, feels as chuckable as an old, rear-drive Escort and invites you to feel as wanton with it as you wish. Which is downright raunchy. So it’s probably just as well that the road roughens up, and we have to slow. Especially as it begins to tighten and climb. The sky darkens, the temperature drops, and suddenly its snowing. We wind endlessly through woods until the track just stops, surprisingly, in a car park. We can’t see much, as a fog of cloud has enveloped the Ferrari and everything else.

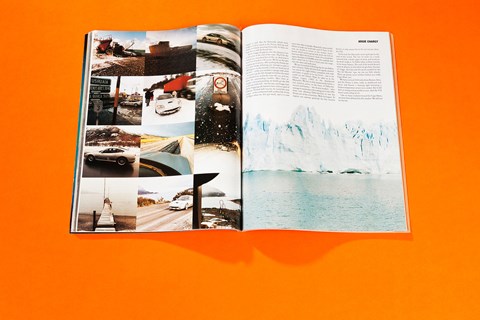

When we get out, we get cold – it really is wintry, here. And then I hear a thunderous cracking noise, and the splash of something massive hitting water. No, it’s not the result of one cheese-and-ham sandwich too many: it’s a slice of ice splitting free and plunging into a lake. We have arrived at Perito Moreno, the biggest glacier in the world outside Antarctica. It’s just that we can’t see it.

But, as we venture gingerly down iced steps towards the lake, it looms into view – a wall of jagged ice almost 200 feet high that glows blue, as if lit from within by neon. It is truly, madly, deeply awesome, and we just stare at it. We see pieces of ice fall away, ice that is over 130 years old, though the chunks seem disappointingly small from where we stand. So, we get closer – until we see a sign that tells us that we should go no further because people have been killed by flying lumps of shattered ice. The next day we visit again, this time in a boat, and in much clearer conditions. As our craft edges away from the glacier, a chunk as big as a detached house shears free. A huge wave breaks silently around it, before the ice splits in two and rolls slowly in the water. It looks like a whale heaving in a final death spasm, or a small ship ceding its buoyancy to the tug of the deep. It is completely and utterly amazing.

More so, in truth, than the vast wastes of southern Patagonia – a land raked by wind so relentless that the terrain is endless nothingness. It’s like that on both sides of our crossing of the Magellan Straits, and both sides of the neighbouring Chilean border – which you must cross to reach Ushuaia, the world’s southernmost city.

When we reach Rio Grande, we are told that we have 125 miles to go, and that 50 of them will be on dirt. The 125 miles pass easily enough, despite the dark of the evening, and so do the first few dirt miles. But then it starts to snow. Hard. Soon we are lit in the reflected light of our headlamps bouncing off the mountains, which pass at no more than 30mph, sometimes less. The Ferrari plods up and down this hilly road easily enough – until it decides it will plod no more.

I feel the momentum drain away, and our 479bhp supercar stops, its rear wheels spinning uselessly. We get out, jack it up, put on the mud and snow wheels carried in the Ducato, and carry on. Actually, we don’t. We have the tyres, but not the rims – they’re trapped in customs at Buenos Aires.

Belatedly, we notice that we’ve stopped by a huge hostel, and from its grounds emerges a maniac on a four-wheel-drive Kawasaki buggy. He enthusiastically tethers it to the towing eye that has been thoughtfully screwed to the 550’s nose, and begins to pull. But the Kawasaki, which must weight a third as much as the Ferrari, flails up and down, its wheels spinning frantically. So then our man tries to jerk the Ferrari free. As the buggy disappears into the distance I see a faint glint at the end of the rope. That’ll be the towing eye, wrenched free of the car. And now it won’t screw back in. Of course. We hit on the idea of going up in reverse. After pulling the Ferrari out of a snow bank, following my attempt to spin it 180 degrees on the throttle, I stick my head out of the door – as the rear window is opaque with snow – to reverse up the hill, though not before the wind has dropped an avalanche onto the car, and me, from the surrounding conifers. After three attempts, and much pushing, we finally get the 550 to the top of the hill – the last one, says buggy man before buggying off, between here and our goal of Ushuaia. Flushed with success, we round the next corner – to be confronted with another hill. It was 10.30pm when we first got stuck, and it is now some time after midnight. Repeated, unsuccessful efforts to make our hotel take until 4.15am. In the end, we decide to return to the maniac man’s hostel, which means going back down the hill we have just taken two hours to climb. It’s a weird feeling to abandon a £150,000 car by the roadside, but that’s what I do as I drive it hard onto the verge, shut the door and walk away.

We are rescued the following day by two Pablos and a Gaston. Pablo-the-first had eagerly awaited our arrival the night before, complete with wife and baby, to guide us to our hotel – just so he could see the Ferrari. Now, he takes us in his Subaru Legacy 1.8GL to the abandoned Maranello. We free it only momentarily before a real solution arrives in the form of Pablo-the-second and Gaston – two Scania truckers – who manage to reintroduce the towing eye to the 550’s front end, allowing Pablo-the-first to tow the Ferrari out of the mountains. With his legacy. To express our extreme gratitude for this favour, it only seems fair to let our rescuer drive the 550.

In the end, the Maranello never quite gets to the end of the world. The last 12 miles are a track covered with a thick carpet of snow, and we know we won’t make it. So Pablo takes us there instead, in his trusty Subaru. The end of the world doesn’t seem to deserve its title when we get there, because it’s foggy. And beyond the point marked by the ‘Fin del Mundo’ sign, we can see little islands. There are plenty more of these before you strike Cape Horn, too.

We have covered 3334 miles from Buenos Aires, and the Ferrari is dirty, rattly in the dashboard and doors and flaunts a warning light betraying a broken temperature sensor on a catalyst. But it still feels as strong and powerful as ever. And the V12 hasn’t used a drop of oil.

Like so many seafarers bound for Cape Horn, we have been defeated by the weather. We will not be the last.