► Driving to the North Korean border in a Mini

► A classic CAR adventure drive from 2005

► Read the full story in our CAR+ archive service

Your visit to the Joint Security Area will entail entry into a hostile area and the possibility of injury or death as a direct result of enemy action. The United Nations Command cannot guarantee the safety of visitors. Fraternisation with the North Korean People’s Army or the Chinese People’s Volunteers is strictly prohibited. Visitors will not point, make gestures or expressions which could be used by the North Korean side as proapaganda material against the UN command.’

Hang on. This is CAR magazine, not News at Ten, and I’m not Kate Adie. The scariest sounding waiver I’ve ever signed is the ‘motor sport can be dangerous’ form that gets you into the more interesting bits of a racetrack. But what do you do when you’re presented with the above by a crew-cut American soldier who, if you sign it, will take you into the weirdest place on earth? You sign.

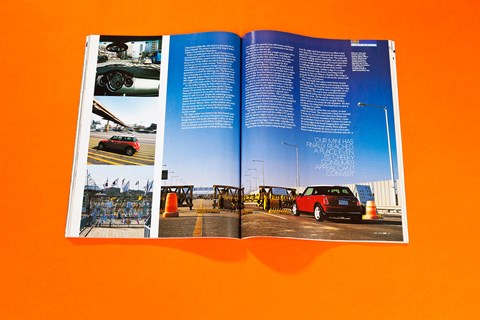

We’re here at the demilitarised zone between the two Koreas in celebration of the fact that the South has just become the 75th market in which you can buy a Mini. Despite the slump, global demand is hanging in there, especially in emerging markets like this one. Much as the original ad campaign became irritating after a while, it takes on new meaning when you’re driving from Seoul up to the border with North Korea. It’s a Mini adventure. Mini reaches the end of the capitalist world. The end.

The fact that the Mini has gone on sale in South Korea is nearly as interesting as the drive to the DMZ. Korea is stuck, geographically and metaphorically, between China and Japan. It lacks the size and potential of the first and the wealth and advancement of the other. And whatever it achieves economically is always marked down by the ‘Korean discount’. In the eyes of the world, economic value created in Korea is worth less than elsewhere because fewer than 50 miles from the capital lies the world’s last hardline Marxist state, ruled by a despot who keeps his 22 million people in a state of ignorance and often starvation, who has a million-man army and nuclear weapons and is so unaccountable and unstable that neighbours as mighty as China have to bribe him with aid just to persuade him to behave himself. The twisted world of Kim Jong-Il makes Saddam’s Iraq look like Glastonbury.

So you can understand why the South Koreans favour the home team; you’d be more inclined to buy British if the Wehrmacht had been camped north of Birmingham for the last 50 years. Of the million cars sold in South Korea last year just 25,000 were made overseas. Times used to be even tougher for car importers; foreign cars used to be refused petrol by garage attendants, and buying one once guaranteed a tax audit the following year. The Koreans are more welcoming now, but they still overwhelmingly want big, affordable, proper saloons and local makers just make them bigger and cheaper. GM had to buy into Daewoo to get a share of this market; Ford’s presence is limited.

So why bother bringing the Mini when it will cost almost twice as much as the new home-grown Hyundai Sonata? For precisely the same reason that the Mini has been such a success in the 74 other, easier markets in which it’s sold. It is cool. Despite the marketing campaign, people don’t need to be told that they want one. BMW reckons that the tech entrepreneurs who work 20-hour days on Seoul’s Teheran Street, and the creatives who make the soap operas and the pop tunes that obsess both the Koreans and the Japanese, won’t be able to get their won out fast enough.

The ‘target market’ was invited to the Mini launch party in a Seoul nightclub, but most of the guests we meet, cool though they are, look barely old enough to drive, let alone spend 20 grand on a car their fathers wouldn’t approve of. They are certainly more interested in fiddling endlessly with their mobile phones and watching the Korean ‘slebs’ arrive than in the speeches from stiff German and Korean car industry executives who, in a concession to the Mini vibe, have taken their ties off.

We get our car the next day, a bright red Cooper with a white roof and every conceivable extra, including the fetish-studded leather trim. Seoul loves it. Every time we stop, a crowd gathers and girls lean across the scuttle, grinning and making V-for-victory signs for their boyfriends’ camera phones. The Mini’s ubiquity on UK roads has cost Frank Stephenson’s styling its impact but in Seoul it feels funky again; we just wonder how a nation raised on big, three-box saloons is going to get on with rear seats that would cramp even the diminutive dictator to the North and a boot that won’t hold his shopping.

Seoul is so crowded that the South Korean president has a plan to build a new capital elsewhere, to free the government from the city’s gridlock and put it out of Dr Evil’s immediate grasp should he invade. Most of the roads are unnamed; you just have a zipcode and a randomly assigned house number. This is probably the chief cause of South Korea’s terrible road safety record; lanes and junctions are well controlled and the standard of driving is no worse than in Italy, but before you reach your destination you have to spend at least 20 minutes cruising the neighbourhood squinting at door numbers.

The Mini is fit for the purpose; the ride is hard over Seoul’s craters and the terrible CVT gearbox holds the thrashy engine at peak revs when you ask for even modest acceleration, but we’d have hated to tackle the city in anything bigger. Solid traffic, unfamiliar city, Mini Cooper; it’s like a Korean remake of The Italian Job.

Most of the time we spend cutting through Seoul’s neon-lit, single-track back streets is in an effort to find some dog to eat. Korean cuisine lacks the international appeal of its Japanese and Chinese rivals. The staple dish is kimchi: cabbage pickled with chillies and a lot of garlic and served chilled with every meal. It’s much better than it sounds, though pungent cold cabbage is unlikely ever to challenge sweet and sour chicken on the world’s favourite Oriental menu. Neither is dog. It’s no urban myth; the Koreans really do eat it, but trying to find someone to serve you Shep on a Sunday is like trying to persuade Mr Bris the butcher to sell you the ‘special stuff’ in The League of Gentlemen.

When we finally find a place it feels furtive; located down a back alley, one rundown room serving as kitchen and dining area. We have the choice of boiled dog or dog stew and, hoping it would be more recognisable, we opt for the former. The meat is tasty; somewhere between beef and dark turkey meat, but definitely mammalian rather than avian. The fat and the curly boiled skin attached to it is a bit too much for our girly Western palates and has to be prised off with chopsticks. We clear our plates, but eating man’s best friend feels too close to cannibalism for comfort.

Still picking the canine from our canines, we head north out of Seoul. The countryside is bleak but beautiful. A sharp, dry, icy wind comes down from Siberia and across the bare brown mountains of the North; I doubt the symbolism is lost on the South. It freezes the water on the rocky edges of the broad Hangang River and freezes the bored-looking conscript sentries whose pillboxes appear more frequently the closer you get to the border. Korea’s roads are good, but the best is the least used, the Unification Highway that runs north and will become Korea’s M1 if the two states are ever reunited. For now it’s almost empty; there are bunkers and ready-made roadblocks but almost all seem to be on the southbound carriageway, ready to trip up Kim’s invading army.

Bright yellow six-inch metal spikes across the road indicate that our Mini has finally reached a place even its cheeky consumer appeal can’t convert. We stop to take a picture but are quickly warned off by a well armed South Korean soldier. I’d argue, but I keep hearing the (slightly modified) words of Noel Coward’s Mr Bridger in The Italian Job. ‘I hope Oliver likes kimchi. They serve it three times a day in the Korean jails, you know…’

To enter the demilitarised zone you have to park up at Imjingak station, from where a recently built but unused rail line also runs north, and board a bus. The border area is pretty much as you’d imagine it; watchtowers, barbed-wire fences, minefields, an anti-tank wall. And a theme park, naturally, with rides, tourist-tat shops and mournful piped music to accompany the monuments to Korean families separated by the Allies’ division of the country along the 38th parallel after its liberation from the Japanese at the end of the Second World War. The Soviet-sponsored North invaded the South in 1950 and had almost overrun it when the UN struck back and beat the North back almost to the Chinese border. With Chinese help, the North pushed the UN south again until in 1953, with the two sides back where they’d started, an armistice was agreed. Who said war was futile?

A line of white stakes was hammered into the ground from coast to coast, marking the frontline. Each side withdrew two kilometres to create the demilitarised zone, though maybe the North should have gone further to get out of range of the southerner’s kimchi-breath. The village of Panmunjeom, through which the frontline runs, was renamed the Joint Security Area and became the meeting point for the two sides. The UN built a hut over the frontline; the table in the middle lies half in the North, half in the South and when the two sides need to speak to each other delegations arrive, sit at their respective sides of the table, and leave again. No peace treaty has ever been signed; in the JSA the Cold War has been put on ice and turned into a tourist attraction.

And the weirdness? Half a century of stalemate and boredom has turned the place borderline insane, with bizarre rituals and behaviour. The North Koreans stand facing each other when on patrol; if one tries to defect, the other has to shoot him first or face a firing squad himself. When not on patrol they sometimes crowd into the ‘Monkey House’, a hut next to the UN’s, and make throat-slitting gestures at the South Korean guards outside. The South Korean uniform now includes compulsory shades so the other side can’t see they’re bothering them, and pebbles sewn into the hems of their trousers to exaggerate the sound of marching. When they’re on guard they take a taekwondo fighting stance: fists clenched, arms drawn back and legs akimbo.

Both sides are capable of staggering pettiness. North Korean soldiers took down the UN flag in the meeting hut and polished their boots on it, so the South replaced it with a plastic one. The South built a 100-metre flagpole just on its side of the ceasefire line, so the North responded with the world’s tallest, 160 metres high with a chain-mail flag weighing a third of a tonne that only flaps when there’s a gale blowing. Fortunately for Kim Jong-Il, there’s always a gale blowing.

The worst incident came in 1976, when the North Koreans took such objection to a UN tree-trimming exercise that they murdered the American officer leading it with the axe he was using. Shooting him would have constituted a breach of the ceasefire. There was a gunfight in 1984 when a Russian on a tour of the North tried to leg it for the South. Maybe he’d heard the Metro had just gone on sale in Seoul.

The oddness of it all, and the sight of Japanese tour groups posing for pictures mimicking the soldiers’ stance, distracts you from the fact that the waiver you sign isn’t just for effect. It is still a war zone, and another incident could spark a war that would turn South Korea from a nation of prosperous, Mini-buying capitalists into something grimmer. Enough to turn a Mini adventure into a major catastrophe.