► Part two of Dash to the Desert, July 1978

► Peugeot 305 answers every question posed

► Classic travel journalism in CAR+

Click here to read Dash To The Desert Part 1

Out of the dunes and back to the mountains – with our Peugeot 305 pushed hard all the way. How did it shape up? Ronald Barker has the answers in the second instalment of our Moroccan adventure.

Now, where were we last month? Look at your map-of-the-world pencil sharpener and see if you can find a tiny dot marked Erfoud. That’s where our hotel was friendly but fresh out of hot water (because of out-of-season repairs) and spare cash in the kitty to swap for travellers’ cheques. We were, you see, becoming rather short of ‘readies’ for petrol, guides and food. The cast was still in good running order (well, Dick the photographer was countering an attack of Montezuma’s Revenge with a barrage of tablets from Tolworth) and the Peugeot 305 likewise. It had now covered 3500 miles since new, some 1850 since Le Havre, and everything about it remained original even down to the water in the rad and the Action air supporting it. The sump dipstick still wet right up the ‘full’ line – it must have been slightly over when we left home –and so the contents of the fuel tank was the only variable.

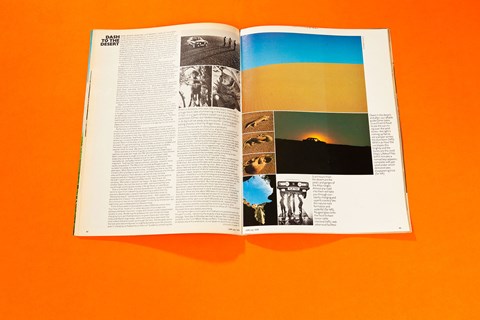

In Erfoud every single eligible male aspires to be a Dune guide, and at 4.30am ours, as agreed, was already waiting in the dark by the Peugeot for us to stumble out – Cherif Omar, a handsome young Moroccan with a high IQ and dressed in blue jeans. The dunes of Erg Chebbi are a small yellow splodge on the Michelin map, remote from other areas of pure sand, and the dirt road to them is tricky with rough sections punctuated by stretches of washboard and vague junctions in the desert waste lacing any indication of which way to where. Omar (derive: home, radar) knew every fold and wrinkle on that road’s surface, and in low tones that did not interrupt conversation, complemented by unobtrusive hand signals, gave the driver almost continuous instructions: ‘More fast! Eighty kilometres here. Slow, very slow, more fast. Left, slower, more fast, eighty kilometres.’ His advice could be relied on absolutely, and he would be ace material for a rally navigator. As an Awful Warning against driving below 80km/h (50mph) on the washboard, he told us of a VW Combi burnt out following a fatigue fracture of a fuel line caused by vibrations. Also of a Spanish tourist who expired for want of water last year after a mechanical breakdown in that area.

Object of the early start was to witness the sunrise over the dunes, sand which can be very beautiful with the play of colour and shade picking out the voluptuous bosomy forms of the dunes. While Dick fired his Nikons, Omar gave a bright little lad who appeared like a mirage from a nomad’s tent lessons (like most nomadic children, he did not go to school) in Arabic and Roman calligraphy, shaping words and symbols in the virgin sand with their forefingers. The boy had brought along a species of salamander to show us, a glossy skinned mottled orange creature known locally as the Poisson de Sable (sand fish) because of its manner of wriggling into the sand to hide from prey and predators.

Nearby was a vast black lake, or so it appeared, of brilliant basalt chips on a bed of sand, and the marks the Peugeot made as we tore across into its centre disfigured the surface with patterns that may take centuries (well, at least a month or two) to obliterate. And, finally Omar led us to an area rich in fossils where you could look down on ammonites embedded in the rock all around. Back in Erfoud he introduced us to a very friendly but glib purveyor of rugs and clothing, who sold Mel a camel hair jellabah and me a junk rug for a fraction of the first asking price but probably several times it value. We were not yet good at bargaining.

Omar wanted us to let him us south-west to Zagora by a spectacular piste (dirt road), but Mel declined because it would have been unnecessarily tough on a car set up for European roads, especially carrying four people and all our gear, and because the ‘everyday car, everyday motorist’ facet of our journey was all important. Tackling that road would have, sensibly, called for more careful preparation. The Moroccan insisted all Peugeots were suitable for pistes, but was fairly scathing about most other makes and types. Most Renaults were okay, including the little 4; but the Citroens 2CV and Dyane were non-U, perhaps because only the later ones with hydraulic front dampers (which he may not have experienced) don’t keep pitching their little noses into the ground. He didn’t seem much impressed by the GS, the CX was too complex, Mercedes in general too heavy. He was in favour of the smaller Opels, but non too keen on VWs, and reckoned that you could forget anything else except a Range Rover or Land Rover.

Dick is a football freak, and was bowled over (for want of abetter term) to learn from a beaming youth serving us petrol that the previous Wednesday Liverpool had beaten Germany three-nil. ‘Allemands kaput!’ said he with obvious relish – then asked if we would do him a favour. If he produced a cassette, could he listen to it for a minute or two on our stereo player? In this fairly remote part we had come upon a dedicated Cat Stevens freak…

From Erfoud west to Ouarzazate is about 200miles and as easy four-hour drive, much of it a rather desolate moonscape over plateaux between mountain ranges with distant snow-topped peaks usually in view. Bordering the plateaux the rock formations keep changing from petrified dinosaurs to green-black wet-look hippo rocks and Welsh slag-heaps, while here and there dark teeth-like land-locked Gibraltar’s push up through the flats. Did the gods sense that we were becoming every so slightly bored because the scenery wasn’t changing so frequently on that run? Suddenly something like a flying saucer loomed up in front of us. A perfectly formed disc of cloud was approaching us from the south-west, followed by another and another, all apparently popping up from peaks along a distant crest and presumably hatched by a bizarre phenomenon of air currents and humidity. As they came nearer we could see that some had dark centres – heavenly poached eggs on a massive scale, giant Polos, aerial jelly-fish or just plain smoke rings? One began spiralling upwards from the centre into a ragged cone, others doomed like mushrooms. Fascinating. For the last 60miles, this route is flanked by numerous castellated kasbahs in the style of children’s sandcastles on the beach but probably owing something of their form to the mediaeval structures of Crusader times.

At Ouarzazate we settled for the night at a modern establishment a mile or so east of the town, the Hotel La Zat run by the French PLM chain. Airy and comfortable with excellent rooms, it lost all the four stars of its rating in the dining room. After and hour’s wait for a dinner table we were very rudely handled by a boorish head waiter and served with the sort of dinner expected of a UK motorway cafeteria – tepid, tasteless consommé or bland veg soup followed by a plain omelette or a slice of rectangular processed ham – or even tinned sardines on toast; then a hunk of cotton wool chicken without sauce accompanied by cold, greasy chips and wet vegetables, or the standard Moroccan meat balls. But had we gone elsewhere, we should never have chanced upon those two charming English gentlemen, wearing neckties and with old-world good manners, who were totally engrossed in a bird-watching holiday. ‘D’you know’ they said, ‘there are only about 400 (was it?) survivors of the Bald Ibis left in the world, and today we’ve seen 21 of them!’ Add in the Editor Nichols and the score was 22! During the day they had been delighted to come upon a can with GB plates and, sure that no one would venture so remotely except to watch birds, tapped on the door, it was occupied by a young Scot and his girlfriend, who promptly told them in no uncertain terms to shove off. You could see the experience was deeply wounding.

During the night at micro-pool of oil had accumulated beneath the Peugeot’s sump; tightening the plug by a few degrees stemmed the seepage. Next day (a Monday) we had to deliver Mel to Agadir, so he could fly to the Turin Motor Show via Paris. Time was now too short to realise one of his ambitions, to run down to Goulimime, a caravan centre 125miles south of Agadir, to watch the famous Blue Men, nomad camel-drivers, ride in from the Sahara. Anyhow, they only do that on Saturdays for the weekly market, so that will have to wait for another visit (the men are not really blue – just their clothes; and it isn’t the sort of caravan centre that disfigures our countryside).

Dawn in the desert, and after: our affable guide Omar takes us out from Erfoud to see the sun rising over the sand dunes – the light is coming up fast as we scamper across the dust basin (left). Within an hour the sun blazes this brightly and the dunes are this vivid (top). Lifeless? No; within minutes a nomad boy appears, complete with pet salamander which demonstrates disappearing trick (far left)

Scant hours from the desert are the peaks and gorges of the Atlas ranges. Almost any road into them will take you through constantly changing and superb scenery like this natural rock formation and waterfall (far left). Peugeot goes onto the hoist to have minor rattle checked (left); was otherwise faultless

So we set Taroudant as our next goal, just a 50mile hop inland from Agadir, with two strong recommendations for hotels. One was for the Gazelle d’Or, suggested by a friend at home and eulogised by Which? Readers, the other for the Palais Salam on the fringe of the town which our birdmen had found enchanting. But at our first roadside stop out of Ouarzazate as we finally got underway for Taroudant, you could have watched three grown men studying the life style of a schizophrenic dun-beetle, its hind legs propelling the captured highball backwards across the tarmac road by an erratic but obviously predetermined course to a patch of soft dirt, where it soon excavated a cavern large enough to absorb the prize ball.

Still the white-capped mountains were around us, and by the road were filed of grain almost golden ripe this far south, wild flowers including poppies in profusion, and fragrant herbs of many varieties. After the pass called Tizi-n-Taghatine (6190ft) there is a spectacular descent towards Taliouine, with streaky bacon rock patterns covering the hills and lush gardens in the valleys of grain and tree plantations. This is an area of almond trees in profusion, and between Taliouine and Aoulaz are forests of argan trees. These squat and thorny, with plenty of space around each growth. Thanks to our Hachette Guide their remarkable contributions to man’s existence can be revealed. The rejected stones are collected by herdsmen, and from the kernels is extracted argan oil. This oil is used for fuelling lamps as well as food preparation (said to be rather bitter) and is also fed back to animals as argan-cake. Finally, the wood makes good charcoal. Sure enough we soon came across herds of goats in argan trees, only the heavy old rams being unable to climb up them and limited to standing on their hind legs to feed off the lower branches.

Lunch was quick and simple – a packet of excellent crisp biscuits washed down with Pepsi followed by ripe bananas from Ecuador, all bought at a small village shop. Twenty miles west of Aoulouz the road joins with the route coming south from Marrakech via the Tizi-n-Test pass (more of this later) and runs over a fertile plain with numerous tributaries to the River Sous, which disgorges at Agadir. Here are vast acreages of fruit trees screen by larger tress, to protect them from strong prevailing winds that, on this day, held the Peugeot back to a 50-75mph peak on full throttle.

Taroudant is a smallish walled town with bastions spaced along its ramparts and a long history. With two splendid hotels, it has to be one of the best centres for exploring Morocco’s south-west. The Gazelle d’Or is set in luscious sub-tropical gardens, out in the country about 1.5 miles from the town, and would be a quiet and relaxed base, But we didn’t want to be insulated from the country and people we had come to see, and followed the lead of the birdmen. Once a Pasha’s palace, the Salam has 75 rooms and is the antithesis of the Gazelle in that the gardens are inside the hotel, several beautiful courtyards with streams running through them and beds of richly flowering shrubs, plus orange trees, banana palms, date palms and bamboo. Tortoises swam, cats caterwauled all night (damn them). The décor is Moorish, the bedrooms are two-tiered and brightly decorated with colourful geometric patterns, and the food is adequate in the European-style restaurant. One fares rather better in Moroccan restaurant (where at last we enjoyed a proper couscous) and the first night there was very vigorous and good-humoured musical entertainment thrown in, lasting until midnight. The local hand drum, held in one and tapped with the other, looks like a Klaxon horn with a skin stretched over its mouth, and rhythmic off-beat hand-clapping is a deafeningly insistent accompaniment for any dance routine.

At Agadir airport, next morning, whence Mel was booked to ascend at 2.45pm, there was a tense hour because his booking had not been confirmed, so he had to queue with the reserves. ‘We don’t want to lose you, but we think you ought to go’, we said, and eventually he went, wearing the Basque beret and the Spanish boots but not the Moroccan jelly-baby. I mean, whoever saw a Bald Ibis wrapped in jelly-baby? But what a mocking Richard and I didn’t realise was that with him in his bag had gone our few remaining car papers! Next duty was a shampoo and set for the car, at a well-equipped garage in the city’s outskirts, where the crew were entertained for a while by the world’s largest grasshopper sunning itself on the forecourt. The Peugeot was then raised on a hydraulic lift to search for the source of a squeak. It was almost certainly in a flexible joint, but the mechanics insisted it didn’t need tightening, and Moroccans are too polite to argue with.

We were booked in at Taroudant for two more nights, and there was only time now for afternoon run to the cascades of Imouzzer des Ida Outanan, reached by turning right off the main Atlantic coast road a few miles north of Agadir. This narrow and tortuous but well-engineered road first runs through a luxuriant gorge, and roadside vendors did their dangerous best to pull us to in flog us ammonites and mineral stones hacked from the rocks. The cactus here were like spiky green Liberace candelabra. Opening up, the road then weaves around the hills, mostly climbing and with strings of lacets which the Peugeot took in its stride, now considerably lightened (no Nichols, and our baggage left at the hotel) until we took a pair of native hitch hikers on board. But had we not done so, we should not have heard of the two-day Fete du Miel (festival of honey) which had just taken place that weekend at Imouzzer. Luckily there was still enough left at an eating house near the cascades for Dick and I to tuck into like a couple of grizzlies. It was served up with fresh bread and butter, and diluted with beer. As far as we could gather, the honey is brought in by beekeepers from the hills all around.

Imouzzer being at the top of its hill, you have to go down a couple of miles to get a view of the cascades, and not much water was falling that day because the supply was being diverted upstairs for irrigation. A apparent phenomenon is that the falls have built up a curiously shaped deposit unfurling from the top like a well-filed garment, rather than eroding a fissure in the rock face. Perhaps this happens when the flow is minimal and the rock face is at baking temperature. At the base is a small rock pool said to be at least 300ft deep. In evening twilight the moon gleamed directly over the pool, frogs creaked, lizards lounged, and there was a scent of lavender.

In Morocco, where public transport is well-established but necessarily infrequent for the more remote places, people ask very politely for lifts and good manners impel you to welcome them if there’s room and they look reasonably respectable. Our guest for the return run was a grey-clocked monkey from an Agadir mosque, and we gave him none of the Roger Clark treatment round the endless hairpins. Among front-drive cars, the 305 is quite outstanding for the refinement of its transmission, with none of the torque reversal jolts every time you open or close the throttle that are unavoidable with many fwd installations. Only a really ham operator would jerk this one – it’s a passenger car as well as a driver’s car. Our monk enjoyed his ride, and asked us in to (mint) tea, which neither of us fancied; we hope it wasn’t bad manners to have declined.

After dark the Agadir-Taroudant road is a bit of a nightmare among the heavies, and the Peugeot’s dipped beams seemed weak in contrast to the indifferent main beams supplemented by M Cibie’s brilliant twin spotlamps, always bearing in mind that a pedestrian or unit cycle may materialise out of the shadows at any moment. That evening Mel rang from Paris; he had discovered our Green Card and list of spare parts in his briefcase, luckily before a touch-down at Tangiers, and had left them at the enquiry desk there, and we should ask for Ahmed. Fine; now we had no car papers at all …

Next day the plan was to do a circuit south embracing Irherm, Tafraoute Tiznit and Agadir, in the hope of seeing a bit of desert and a few camels. For the first 55miles there was excellent tarmac, the serpentine road nowhere steeply graded; just short of Irherm it turns right for Tafraoute and the real dirt begins, the broken rocky surface demanding constant vigilance and often 10-15mph is the discreet limit. Fifty miles of this allowed plenty of time for enjoying the scenery and roadside flora, and peering down into fertile valleys with huge round enclosures among the cubist huts, probably for drying grain. During this section we had met one car and two mopeds. At Ait Abdaklah, a predominantly military encampment, we sipped Coca Cola in a sleazy café while watching local kids play a clapped out football machine with astonishing speed and skill. A few miles further, at Titeki, the road was transformed into brand new tarmac for a superbly picturesque descent towards Tafraoute. A large hotel complex was under construction, and there were fancy houses around to confirm that this was a refuge for the wealthy; massed tourists would soon be spoiling it.

Tafroute itself was rather dead, and after a brief snack there we decided it was too late in the day to continue to Tiznit and to return more directly via Ait-Baha since we were told the road thither had been improved since our map had been printed, and this proved to be the case. Once-difficult sections had been cut and quarried to ease gradients and hairpins, and in a few years time much of the adventure of travelling here will have been removed.

But it was time now to point north again, with the homing instinct becoming stronger, spoilt by the prospect of having to slog up through Spain and France without the time to enjoy them. Between Taroudant and Marrakech there are about 135miles including some of the most spectacular sections in the country, including a rise to nearly 6900ft to clear the Tizi-n-Test pass. We snaked up on the well-surfaced though narrow road, scented with lavender and other fragrant herbs and bright with spring blooms too numerous to mention, especially as we didn’t know what most of them were. At the top was a primitive refuge with crudely written ads for the inevitable Coca Cola and cassecroute, and symbols for tea etc. Outside were two herdsmen with a goat and its new offspring, a dog and a mule. A monument records the engineering feat of making the road, accomplished during 1926-1932, by the Moroccan Public Works Service, and lists those chiefly concerned in a classic pyramid of power and authority. You can imagine the bucks of day-to-day problems being handed up from one to the next until they reached the unfortunate M Joyant, but presumably he had someone even grater to turn to before the President of France was notified. NM JOYANT Director-General, DELANDE Ingenieur en Chef, MARTIN Ingenieur Ordinarie, CONTANT Ingenieur Subdivsionnaire, GAUTHIER Ingenieur Adjoint.

After the T-n-T the road surface changed colour with its surroundings, abruptly brick pink to pewter and back to pink at different strata, and here there are stone houses, reed thatched and topped with mud, built on terraces around pewter pinnacles. At lunchtime we stopped near Asni at a quite small but smart roadside establishment with a proud name, the Grand Hotel-Restaurant du Toubkal, Jebel Toubkal being Morocco’s highest mountain (13,660ft) and set in a national park. The peak is one among many in a magnificent backdrop to the hotel; for Dick it was a nostalgic sight because as a teenager he had once camped near the summit. Inside the restaurant there is elaborate plaster décor in Moorish style, and the atmosphere of well-to-do relaxation that goes with an abundance of clean white linen. The maître d’hotel was formally dressed with black bow tie; he offered us salads Niceoise and fresh solo meuniere which had left Agadir at five that morning, and delicious pastries, which we at on a terrace outside, overlooking the rose garden. No wonder that Winston Churchill used to patronise this restaurant and sometimes paint in the garden. He is remembered as trés sympathique, a simple, informal guest who never wore a tie or made special demands on their services.

Over the past 30years another famous Briton has often patronised it for Sunday lunch, followed by a short snooze before returning to his apartment in Marrakech – Field-Marshal Auchinlek, The Great Auk – now in his 90s. He is chauffeured by his eccentric Arab domestic who dresses to simulate Charlie Chaplin, even to the bowler hat. We sat and watched a stork wheeling high overhead. Then, as though the control tower had given it the OK to land, the great bird began losing height, swept low over our heads and stalled for touch-down on one of the hotel chimneys, followed by a great clacking of beaks with its mate which we hadn’t noticed on its nest until that moment. The stork family returns there every year, and twice came back after their nest had caught fire; that particular chimney is never used now.

Outside, small boys vied to sell us extravagantly coloured mineral samples, some very beautiful but the sort of thing that has so much more value if you yourself have picked it up. As a parting shot they held up in the macabre offering of a fairly fresh looking head of a black goat. In Marrakech we could spare only an house in the Place Jemaa el Fna, just as the entertainers were beginning to gather for the evening diversions – snake charmers, musicians and dancers, the Koran-bashers and story tellers, acrobatic monkeys – and milling round them the hippies and hustlers, tourists and beggars, refined Englished ladies with summer rocks and blue rinses, white handbags and peeling red arms.

It was hot in the air still in Marrakech; our schedule was tightening, but the road north to Casablanca runs dead straight for mile after mile, it is smooth and wide and neatly edged, so fare for cruising at 80mph when you’re prepared to risk a brush with the gendarmerie. Without papers we could have been in serious trouble, but in fact were never stopped even when the roadside checks were being made. Beside the road were enormous acreages of ripening corn or almond trees, right up to the verge, sheep and cattle grazed, and there were several small groups of camels with their young.

That evening we settled in Kenitra, a township created from nothing in 1913 (according to Hachette) about 25miles up the Atlantic coast from Rabat. Frogs in a man-made marble pond opposite the hotel croacked louder than the traffic through the night. During the dash to Tangiers next morning we stopped only for a saunter around the remains of Roman Rona Lixus just north of Larache. They are quite extensive and well preserved, but no one seems bothered about protecting them from thieves, and vandals. Alongside the roadside there were stork nests lodged on lopped trees only a few yards from the thunder and backdraughts of mighty trucks; they seem to welcome the human presence and are unruffled by the din and poisonous fumes. And we overtook a Renault 4 containing three adult men and more than calf-size cow. Sighs of relief at Tangiers airport, where our car papers were handed over and the obliging staff would take no payment.

For reasons of economy we decided to return to Spain by sailing to Algeciras via Ceuta instead of Tangiers, Ceuta’s Monte Hacho being the second Pillar of Hercules opposite Gibraltar and which cuts down the voyage by about an hour. Were we unwise to buy our tickets in Tangiers? We hadn’t noticed a message printed in red on them that they had to be presented 2.5 hours before embarkation, but fortunately they were honoured without delay. At Ceuta there is a lot of paper ‘bull’, with chits being handed back and forth to no apparent purpose but we had no problems. In Algeciras, however, the Spanish customs people are methodical about searching cars, tapping their door sills and searching under wheel arches for hidden caches of you-know-what.

We had covered just under 2000miles in Morocco without any form of breakdown, without adding water to radiator or batter or oil to the sump. The only spare part used was the carburettor air filter element, which, frankly, we changed in Taroudant to get rid of the package rather than because the used one was dirty. The only adjustment made had been made to the headlamps, because the two-way triggers behind each lens do not provide quite enough change in beam angle to cope with our sort of load, and the meagre tightening of the engine’s dripping sump plug.

Returning to Spain lost us the two hours gained on the outward journey. Knowing no better, we decided on a different route north, via Cadiz, Seville, Caceres, Valladolid, Burgos, and into France by the Motorway running through the frontier into Biarritz. Seville was totally involved in a week’s fiesta, with children and pretty girls everywhere in party frocks, handsome horsemen in national dress with their ladies riding side saddle-pillion on immaculately groomed stallions, groups of horses tethered outside bars and restaurants, hordes of men, women and children all walking somewhere else in different directions, with the determined expressions of people who knew where it was, or would be. Could we join in the fun? No, because there was no room at any inn. So we ate, and pressed on north, and suffered, in darkness, one of the world’s worse roads, terrible surfaced, with unmade edges, diabolical hairpins left and right always just over blind crests, and the whole lot garnished by a continuous stream of enormous trucks mostly coming in the opposing direction. Thank God for the ‘mark’ lamps on the tops of trucks which suddenly rise from apparently flat roads and give you welcome warning of yet another super truck approaching from an unseen trough. This vision of Hell lasted for perhaps two-thirds of the 125 miles to Merida, where we found a motel with spare bedrooms but I had to join a bingo club at three in the morning to get a stiff glass of whisky to put me to sleep.

Spain in April has lots of storks, too, on almost every church tower and many less likely places. The daylight run was uneventful apart from several miles of first and second gear creeping on an unmade road before Plasencia. A night in Biarritz, a leisurely rush up through France on almost exclusively minor roads of excellent quality and great charm right up to Le Mans, and finally a latish arrival at Dieppe where there hadn’t been a boat for hours and there wouldn’t be another until 5.30am. The receptionist at our favourite Hotel Windsor on the sea front watched patiently while we turned out our pockets and counted the travellers’ cheques. Mercifully there was enough for eating, for sleeping, and even for buying a boat ticket tomorrow. The Peugeot’s milometer now read 6238, of which our share had been 4665, and there was still the matter of Newhaven to London via here and there. Nothing had broken of an adventure-seeking tourist with a fortnight to spare, and a good set of wheels; but of course there was one rather big difference between Us and You: we could put our petrol bill down to expenses.

What we are left with now, all three of us, is the strong yearning to return to Morocco for yet another sampling, and as quickly as possible. It is marvellously friendly and interesting place, a country of scenic drama as well as sheer beauty. It is easy for Europeans to reach and in which to travel but it is so excitingly different from anything on the Continent. Its people are polite and helpful, and its authorities, if our experience is anything to judge by, are sufficiently casual or understanding to let tourists roam as they please. You can expect to pay about £8 a night for a very good hotel room, although most formal meals will cost around £3 and crossing the Straits of Gibraltar will be about £8 for a 305-sized car and two people. Petrol in Morocco is £1.40 a gallon. Unless you’re bent on driving through the night, you should plan on spending two nights at hotels in France and Spain on each of the out and back journeys.

And what, in the end, did we think of the Peugeot 305? A car has to be good to stand up to the scrutiny of people as finicky as us for two weeks and almost 5000miles. The Peugeot did, and in its own unassuming way just kept impressing us with the days and the miles. It has excellent seats and a spacious cabin – and as those roads through Spain and the stretches of dirt in Morocco proved, its suspension is truly superb. Its handling is accurate and enjoyable, its roadholding tenacious; its engine is smooth and willing and if it could occasionally do with more power or another gear, while laden as heavily as we had it, its performance is, overall, brisk and satisfactory. It is not a notably quiet car, but it is not noisy either. It took everything we encountered fusslessly in its stride allowing us to enjoy Morocco to the full. Better still, we each enjoyed driving the car as much as we did riding it, its comfort level is better than most bigger cars and in its market segment that makes it a very complete mid-sized family saloon indeed.

Click here to read Dash To The Desert Part 1