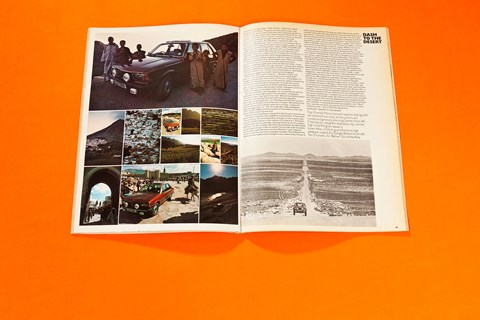

► One of our most audacious drives from 1978

► Can we reach the Sahara in a Peugeot 305?

► Classic travel journalism in CAR+

Click here to read Dash to the desert part 2

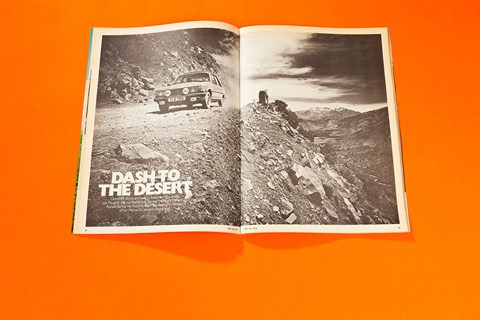

It is dawn in the Sahara. The car is a Peugeot 305, driven hard from Britain. The task? To see how a modern family saloon copes with a man-sized test… three people, 14 days, 5000 miles and the rugged magnificence that is Morocco in the spring. Pictures by Richard Davies, story by Mel Nichols and Ronald Barker.

It seemed the natural thing to do – take the latest Peugeot to North Africa. Peugeots are traditionally tough, well-conceived cars able to cope comfortably with long trips and difficult conditions, and they seem inextricably linked with North Africa – not just because of the link with France in the past but because the 404, in particular, served well enough to become the motorised equivalent of the camel. The 305 doesn’t replace the 404 – the forthcoming 405 does that – but it is very much an everyday family car pitched into the big volume sector of the market (it goes on sale in Britain this month at these prices: 305GL £2999, GR £3299, SR £3599). Why not, we thought, see how such a car handled a two-week expedition to North Africa by way of an introductory test? There was, of course, a certain amount of hedonism involved, but, to keep in reasonable touch with reality we decided that our journey had to be one that could be made by any British motorist interested in finding somewhere a little off the beaten track. Maximum interest with minimal hassle in accessibility and bureaucracy meant Morocco. It had been eight years since we were last there – to put the then-new Range Rover through its paces – and we were looking forward to updating our impressions of such a fascinating country, This time, however, our ‘normal motorist/everyday car’ parameters would keep us away from camel tracks across the desert.

Because the 305 is such a new car – unknown in Spain and Morocco – we carried an unusually large story of spare parts. Peugeot, with precious little time to run the car in and prepare it (it was the first rhd production car into the country), gave us everything from the obvious set of belts and gaskets to things like a clutch plate, valve springs and even complete with headlamp units (they’re unique). We also took a second spare wheel, emergency containers of petrol and water, a complete toolkit and a compass.

The top line 305SR is well equipped; our car also had the optional £265 pack which provides electric front windows, tinted glass, laminated screen, map light and sunroof. We also had lhd dip pattern headlamps, and two big Cibie spotlights and two fog lights.

Amazingly, all the equipment, our three bags and Richard’s camera case went into the boot with a little to spare. We swiftly found that the 305 was fairly roomy inside too (cunningly, it looks and behaves bigger than it is: 13ft 10in long, 64in wide, wheelbase 103in, weight 2068Ib) and the prospect of two weeks on the road did not seem a daunting one at all.

After careful checking our equipment (but failing to note that we did not have a log book!) we headed for Southampton. A Townsend Thoresen ferry (reluctantly boarded, although its cabins were clean and comfortable) had us on the road out of Le Havre at 7.30 French time the next morning (Sunday), heading directly south for Le Mans and Tours. On the run down the M3 to Southampton the 305 had felt just tail-down enough under its load for the attitude to be noticeable but its stability and ride were not at all affected. It was, however, slightly noisier than we had anticipated: between 70 and 80mph the engine sounds slightly fussy, brought to your attention by the lack of road noise and wind noise. The twisting roads of Normandy swiftly revealed impeccable handling and quick, accurate steering devoid of fwd reaction. The quality of the drive-train was also coming to light: absolute silkiness as the throttle was applied or released, so that the car could be brought very smoothly and cleanly into the bends and powered out again without a trace of snatch or judder. The 1472cc/ 74bhp at 6000rpm engine (the GL and GR have the 1290cc unit) was smooth and willing enough to pass for a good 1600 but we could have done with more capacity or a fifth gear for passing trucks.

We escaped the collapse of the Wilson Bridge over the Loire at Tours by minutes, picked up the Aquitaine autoroute for Poiters then continued on to Angoulême. Slow traffic prompted us to switch then to a ‘yellow’ road to sweep to the east of Bordeaux. The faithful Michelin Guide found us the superb Hotel des Pyrenees at St Jean-Pied-de-Port near the Spanish border and we were greeted and fed exquisitely at nine on a Sunday night. Despite a brief blizzard, we were in Pamplona within an hour the next morning, and we’d recommend the route (D933/C135). Atrocious roads heading for Madrid had us in growing admiration of the 305’s suspension and seats; we held 70 to 80mph in perfect comfort. Toledo – quite staggering – was worth the small detour; the hotels were full so we stayed nearby and went back the next morning for two hours’ exploration. More appalling roads down through Ciudad Real but through often dramatically beautiful country and the Peugeot competent, refined and relaxed enough to allow us to enjoy it. East of Cordoba and down to Malaga (our destination for the night) we struck rain and deep puddles on the road. Here, we found the Peugeot had far more grip than one associates with Michelin ZXs. It never put a wheel wrong and handled so beautifully that we were in fact able to despatch the last 100miles with astounding swiftness and real riving pleasure. It had been flat out for nearly 300miles on that leg but returned 28.5mpg. With Morocco still to come, we were well impressed. Next morning (Wednesday) we cruised along the coast to Algeciras, washed some excellent freshly fried squid down with cold beer in a quayside bar while we waited for the 1.30pm ferry; and then we were crossing the Straits of Gibraltar in warm sunshine at last – with all Morocco ahead of us.

So here we sit on the Tangier dockside, cutting washers out of the Peugeot 305’s seats with apprehension, half a bootfull of spares and tools being scrutinized by the customs and this powerful-looking official sheltering under the straw titfer asking to see the car’s papers. Horrors! The Carte Verte (insurance) we have, the Carte Grise (log book) we have not. How long might we be stuck here, exposed to all Tangier’s moral pitfalls, before missing document can reach us? Miraculously M Strawhat’s attention is suddenly diverted towards some other migratory prey; one of his colleagues slams our boot shut and waves us away. Good Lord, we made it. But if Ché Melvary persists with his Basquerade as a four-stroke revolutionary under the provocative beret he bought in the Pyrénées we’re bound to be stopped by highway patrols who will ask to see the car papers, and it will add to the story to report first-hand on life in a Moroccan gaol. One Ché leads to another, and the Bedrof family motto: Ché Sará, Sará (whatever will be, will be) fits our predicament admirably.

At this stage Morocco, for us, consists of one 1978 map (Michelin 169), Holiday Which dated September 1977 and Hachette’s Guide Bleu in English 1966, and because of not having a log book we cannot apply for the tourist fraction of cut-price petrol coupons, the going rate without these being about £1.30 a gallon. It’s worth noting, too, that the crossing from Algeciras to Ceuta, rather than Tangier, is much shorter and therefore both quicker (by an hour or more) and cheaper. Ceuta, which Moroccans know as Sebta, is an eight square mile patch of Spain, all they now have left in North Africa apart from another Med seasport, Metilla, near the Algerian border. It forms a sort of isthmus, quite a lot of which consists of Mount Monte Hacho, one of the Pillars of Hercules; the other is Gibraltar. Just as the Spanish are less keen about the British occupying one of the Pillars, the Moroccans don’t exactly welcome the Spanish on the other. If you don’t happen to have all the necessary papers, the odds on slipping in unobtrusively are probably better in Tangier where the border atmosphere is less strained and formal. Why didn’t we have a log book? We had everything else – and as we checked it all before setting off for Southampton, we failed to see that the otherwise incredibly efficient Peugeot had somehow forgotten to slip it into our document pack. Then again, we were somewhat preoccupied making sure we had the correct bail bond for Spain! That’s the really important one.

For those who didn’t know it, one cannot step ashore in Morocco, hire a camel and set off into an infinity of Saharan sand. A great deal of the country consists of spectacular mountain ranges – the highest in North Africa – interspersed by vast plateaux and plains. The Saharan bit south of all this lacks properly defined roads and is no place for inexperienced and unaccompanied tourists, especially now while there’s a tension almost amounting to war with neighbouring Mauretania. As it is, there are large areas of infertile wasteland where not having a compass, plenty of petrol and a supply of drinking water can easily lead to dry bones.

In the north there’s a crescent shaped range matching the Mediterranean coastline, the Rif; below this, and spanning the country diagonally from north-east to south-west are the great Atleas ranges – Middle, High and Anti – with the first two extending into Algeria. In the mountainous districts there are, of course, few routes with metalled roads and M Bibendum’s codes by colour, width between parallel lines and type of line (green-bordered, continuous, and broken) are invaluable aids. Even ‘yellow’ roads with continuous borders can be astonishingly primitive in places, and white roads with a broken line one side are sometimes difficult to find in the first place and may disappear or divide into three unsigned directions after carrying you confidently into the centre of an apparently limitless and featureless moonscape.

Some of the ‘red’ roads are superbly engineered and adequately wide, some are smooth but narrow with unmade borders so that two wheels have to take to the dirt when meeting other vehicles; and some stretches of ‘yellow’ roads have become highways since our map was surveyed. Morocco is being opened up for tourism, and navigation will become easier with every year. If in doubt about a route you have only to stop the car in a town or village and a throng of eager advisers will soon accumulate. Even when you’re miles from anywhere and apparently quite alone, a shepherd or nomad will appear. Most of them have at least a smattering of French; many are fluent, and this was useful later on.

Crossing the Straits of Gibraltar ‘gained’ us two hours, so that 4.30pm was suddenly 2.30. At 2978 miles from new, 1316 since leaving Le Havre, the Peugeot was aimed south-east out of Tangier towards Tetouan, with plenty of time to reach Chechaouen (sometimes Chaouen), the night’s objective, a mere 70 miles: we wanted time to see this town in daylight, and generally avoid nocturnal marathons. Going this way, as distinct from the Atlantic coastal route towards Rabat and Casablanca, there is no gradual acclimatization from European to Berber and Arab people and their backgrounds. The moment you leave Tangier the people along the road are all very native, the women always walking, the men more usually sitting on their asses or mopeds. Most of them could have stepped straight out of the canvasses of biblical scenes by the Old Masters, for their fine features as well as their clothing.

There are trucks mostly by Volvo (who have an assembly plant in the Kingdom), Daf and Berliet and menacing great coaches by the same makers, always full to the brim and their roof racks stacked with everything from cycles to propane bottles in addition to miscellaneous luggage. On the level they move fast and only suicidal car drivers would compete with them for road space. Having to follow one on a slow climb often brings one back to Liverpool Street Station in the Steam Age – clouds of stinking black smoke; but their drivers are mostly courteous, flashing green signals or waving you on when the road is clear. Sometimes the driver of an oncoming vehicle appears to raise his fist at you behind the screen, or the outstretched palm of his hand; what have you done to upset him? Nothing! It only happens where the road if unmetalled, or where either or both vehicles have to put two wheels on the dirt, when pressure inside the glass can prevent it shattering if hit by a stone. In some sections we saw remnants of toughened screens all along the roadside. Our 305 was fitted with a laminated screen, and if you’re in Morocco-bound you should take this precaution.

A few miles out from Tangier the road climbs and you have a fine view behind the plain of Tangier. A mile or two short of Tetouan, which is on the main route to Ceuta, the Chechaouen road turns south, and at this point one can see it spread out on a plateau below, predominantly white and enticing with it walled medina (old town), towers and marinates. Like most Moroccan towns it has a less concentrated and compact European section to remind one of the period 1912-56during which the north was a Spanish protectorate and the rest French, since when it has been an independent kingdom. At first the road south from Tetouan runs between ridges along the valley of the Hajera river, then climbs between the peaks topping 7000ft, still snow-capped in April. Sadly, the Berber villages in this area, once thatched, are mostly now roofed with corrugated galvanized sheeting which glistens somewhat unromantically in the evening sun where it still reaches into the valleys. Although traffic is fairly sparse, there are frequent roadsides vendors offering round goats milk cheeses. They run into the road and try to wave you down, but smile cheerfully when you wave back and drive past.

Chechaouen is just the place for your first night in Morocco. It’s just off the main Tetouan-Fes road almost free from motor traffic, about 2000ft above sea level and built on the lower slopes of a sheltering mounting. You enter it through the newer Spanish suburb and arrive in a small, open square surrounding a lush garden. Stopping here to think of the next move we were immediately assailed and hassled from all sides, mostly by amazing multi-lingual kids hoping to pick up a dirham (eight to £1) or two to guide us to a hotel, or a ‘very cheap house where I live with my brother’, or to the medina. Which doesn’t help, but Hachette recommends the Parador hotel in the Place de Maghzen, a little further up the hill on the fringe of the old town, and the end of the road for cars.

It’s a peaceful and well-equipped hotel with agreeable service; Moroccans are polite, cheerful and helpful without being servile, and thus also sensitive to good manners. Not everyone who tries to help wants a reward for it. We should have liked Moroccan food rather than the uninspired though adequate European style provided, but the trade knows most tourists are notoriously unadventurous and nervous about upsets if anything ‘new’ is dropped in their feeding troughs; even the feeding troughs in hotels.

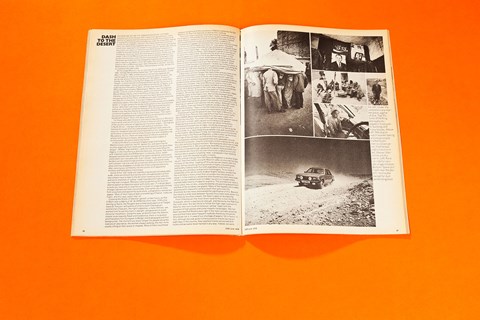

Only a stone’s throw from the Palace de Maghzen is another larger square, free from traffic and with Moorish cafés on one side facing a mosque on the other. Leading off this are narrow streets with tiny shops selling everything from pyramids of highly coloured spices and healthy-looking fresh fruit vegetables to all forms of clothing, pots and pans and general ironmongery. To our eyes it looked like a film set for some Arabian Nights fantasy, except that the truth here is more unreal than any props man would dare to show it. In the medina’s residential area mysterious dark alleys lead off the narrow cobbled lanes to hidden squalors or maybe totally naïve cubist, box-on-box, unadulterated by any planning department and few of the windows are glazed. Many of the façades are crudely splashed with a beautiful ice-blue wash that spills over the threshold but we never discovered the significance of this. Beyond the medina a wide walk between fig and citrus trees leads down to a fast flowing mountain stream, the town’s open-air launderette.

From Chechaouen the most direct route to Fes is over the Rif to Quezzane, then turn south on tortuous ‘yellow’ roads with the prospect of high passes and some majestic landscapes. We had been warned that Ketama was right in the main cannabis growing area and that there were frequent roadside checks by the Police. Should we risk it, in view of our shortage of papers? All in favour. In fact, although we saw quite numerous police checks during out eight days in the country, they seemed mainly concerned with trucks and we were never harried in any way. Indeed we were ushered through with a polite ‘bon voyage, messieurs.’

A the first roadside stream after Chechaouen our Box Brownie expert insisted on a cold shower and rub down for the Peugeot. We had no bucket, but we did of course have a big water carrier; we didn’t have a sponge, but the Editor had a pair of socks that needed a wash … and we did have a make-believe substitute leather. The car sparkling, in a few miles we were flanked by snow-covered peaks as we climbed through the Bab Taza Pass along roads bordered by spring flowers and up into forests of fir, holm oak and cork oak, through the Bab-Berred Pass at just over 4000ft. It is such big, open country: the valleys deep and long, the peaks high, sometimes miles off, and the road often visible, climbing higher and higher, miles ahead. And the air so clear and crisp in the thin sun shining down on to the mountain tops.

And then quite suddenly, while driving along the ridge with these great panoramas of mountain and valley each side, and apparently quite alone, we came across people and vehicles by the roadside and, on the Mediterranean side in the lee of the ridge, looked down upon a huge concourse of people and animals. It happened to be the day of the weekly cattle and fruit market in this remote but lovely place, and an area of perhaps two acres was a seething concentration of life (death, too, in a make-do slaughterhouse) and hubbub. Cattle and sheep and goats for barter; mules, donkeys and a few small dark horses for transport, stalls heaped high with oranges, vegetables and even household needs like packets of Omo. It was cold enough for pullovers and jackets. While Richard strolled about snapping local colour with his Japanese birdie-boxes Nichols and I were good-humouredly but very persistently pressed to buy hashish – and other wilder pleasures were graphically suggested by a leering character who called in English: ‘Come along, I like old men!’ Subtle lot, these Moroccans.

Still the ridge rose until we reached the snowline and drove through a forest of frosted cedars at the 5250ft Pass of Bab-Besen, where on a clear day one can see across to the coast. The Peugeot handled the climb with aplomb, pulling steadily in third and top: the prospect of the snow hadn’t worried us – we knew from the blizzard in the Pyrénées that it could cope well enough in the slush. Six miles more brought us to Ketama. What we saw of it looked a bit of a shanty town among the cedars, but it is, in fact, a budding ski resort so there must be more that we didn’t have time to investigate. Here to welcome us at the filling station was an old friend from Italy, the six-legged animal from Agip.

It’s a 50mile run south from Ketama to Taounate, the scenery down from the ridge changing to rolling green hills with cactus, gorse and many varieties of wild flower now in bloom. This is good Peugeot country, too, where the tenacious grip (via Michelin ZXs) and stability could be exploited because the steering is so responsive, with quite a bit of feel coming through, and the ride so well balanced that the passengers don’t complain. They just sat and took in the dramatic landscape. With three up and an overload of spares and things in the boot it could have done with another half-litre in the cylinders to boost the torque at this altitude, but the slick gearshift and frugal consumption were compensations. We had swiftly discovered that it’s certainly one of the few cars in this class that treats its rear seat passengers almost as well as those in front. None of us liked the brakes much, which lack early bite and need more effort than expected with a servo to assist, although they never (like old soldiers) faded away or gave a moment’s worry.

At Taounate there wasn’t time to enjoy a Bain Moderne El Fath (would there be massage too?), only to relish fantastic views over vast green plateau, sprinkled with red and yellow spring flowers. There’s an extraordinary thing about Morocco that you might not realise if you’ve never been round the other side, which is that much of everything you see there has its match in Australia. ‘Ah!’ Mr Editor Nichols was apt to exclaim, just as a spectacle quite unlike anything Dick and I had yet seen was suddenly revealed, and our senses were trying to absorb something of it and pack the information into the brain cells: ‘Just like the run into Gundagai!’ This place’s claim to fame, we were then informed as if we should have been familiar with such gems of Australian culture, was that, in some old song: ‘The dog sat on the tucker boxes, nine miles from Gundagai’. ‘Never mind about dogs on tucker boxes,’ we said: ‘What about Morocco’s goats in trees?’ Sooner or later we knew we’d find some, and that shut him up once and for all.

Five miles south of Taounate you cross the Oued (river) Ouerrha into Ain-Aichae village and now the roads are tree-lined with green crops all around, and small conical hills protruding from the plateau with olive trees growing in terraces around them, like pom-poms on a clown’s hat. Outside a tiny hamlet we saw women preparing a fire in a clay oven shaped like a beehive, ready for baking the day’s bread. We went up the track to ask if we might watch. It takes only a few minutes to bake and we were promptly invited to sit down and share it with the men, but the women discreetly disappeared. Bowls of liquid yoghurt were handed round, with lots of refreshing mint tea. The men smoked hash in a small pipe, offered politely to us but with no pressure and our refusals (none of us smoke, full stop!) were accepted easily. We spoke in French of all manner of subjects from storks to cannabis growing. It seemed there was a stork’s nest on one of the men’s aunt’s house just down the road. The uncle had died and left her with five or six young children, mostly with runny noses and sores on their faces, but the familiar Moroccan smiles. Only a little girl was shy. Perhaps Little Girls’ Lib will come one day, with Muslim Womens’ Lib. The aunt’s house was a mud hovel with rather squalid surroundings, remote from other dwellings. She didn’t appear but sure enough there was a stork nesting above. Apparently stork families return year after year to the same nesting places and are welcome guests, but you mustn’t try to touch them or get on familiar terms. The male is the larger, and when the eggs are hatched male and female take turns to sit or forage for food.

Amid the lush green of these valleys, the gutted skeleton of an orange MGB GT lay forlorn by the roadside – smashed on hash, perhaps, paraphrasing that Cadbury ad for instant Murphy. In the afternoon light the fields were yellow, blue and purple, and the walled medina of Fes, covering about a square mile, came into view from several miles distant. A road encircles the old walled city, which has a haphazard outline punctuated irregularly by formal crenelated centrances, and taking this road anticlockwise brought us up to high ground north-west of the city near the tombs of the Merinid dynasty. From this vantage point the prospect is mind-bending: the sheer compression ratio of buildings within the walled area and the knowledge that a huge proportion of Fes’s quarter-million population live in the medina, with how many more crammed into it in daytime when merchants and buyers and artisans poured in … and then the coachloads of gawping tourists (like ourselves?) ready and eager to digest the city’s delights.

Without a guide (human or paper) one could soon become disorientated in the narrow cobbled alleys which might be frightening in such a throng. But if you keep in one direction rather than in circle you are bound to reach the wall somewhere, and if you look pathetic someone will rush to help. Should we spend the night at the Palais Jamai, just outside the wall? It looked a bit large and formal, and to be attracting migratory flocks of familiar species such as Thompson’s Group, who can observe visibly ripening by day in their glazed charabancs. Instead, we chose the modern Merinides, high on the fringe of the bowl, the complete antithesis of the way of life in the old city below.

Supplementing the brass-badged official guides are myriads of quick-witted small boys and youths anxious to precipitate a windfall of dirhams from well-heeled and gullible tourists. We had declined the services of one unofficial guide at the hotel, but when we found ourselves at one of the city gates with no other in sight we wished we hadn’t. But we were soon rescued by a diminutive Artful Dodger straight out of Dickens, except that his name was Ahmed. He knew a good eating place right in the middle of the medina, but had to lead us from a distance in case the city police spotted him, which would mean three days in goal because he was under-age to be a guide, After a plate of fine soup it was rather dry-chicken-and-chips washed down with Coca Cola, just like on gets in Newquay or a motorway caff. Mel and Dick did better with local meat balls. In the late evening many of the tiny shops are still open, stacked high with every sort of merchandise for eating and wearing and decorating the household, while craftsmen labour away in gloomy caverns dimly lit by low wattage bulbs, beating copper, chasing Berber silver and brass, welding and soldering, cobbling and weaving. Perhaps the most intriguing and seductive of Morocco’s imperial cities, Fes has somehow survived an incredibly chequered history, and you would need several days to really get to grips with its architectural treasures and unique vitality. What a place; another world altogether – and still we have been in Morocco little more than 24hours!

With 1560mile covered since Le Havre, the 305 was still completely intact apart from an occasional squeak underneath from a slack exhaust bracket. The radiator level was normal, the sump dipstick indicated full, and the overall consumption had been excellent considering the pull through the mountains and the previously very exacting dash through Spain. Our next goal, Erfoud, lay some 275miles due south and over the humps of both Middle and High Atlas, where they obligingly not too high. After green plains to Sefrou there is a barren red rocky plateau, and it was here that we achieved 100mph on the clock for the first time. Steadily, with the road predominantly straight, we started climbing towards towering snow-capped peaks, the land around us spreading out to their bases; above, glorious bright blue sky.

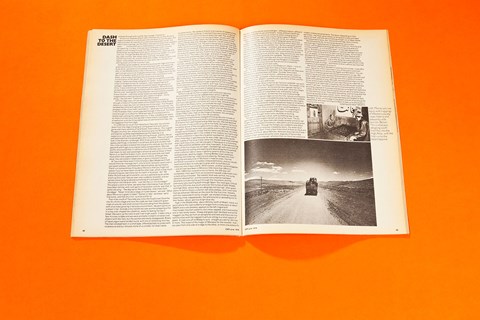

High in the Middle Atlas, about 40miles north of Midelt, there is a point where the road suddenly emerges from a rocky pass at about 5700ft and a vast Plateau appears to the left ringed with moonscape mountain patterns, but snow-capped, and traversed by one or two lonely tacks. Sheep and goat look like black and white maggots (as they do from an aeroplane) and here and there are tiny communities with flat-topped mud huts sitting in a small splash of green. A road runs of at 90deg to ours: straight as a die for 20 miles or more. This is part of the magic of Morocco for the traveller, that you pass from one side of a ridge to the other, or from one plateau to the next, and the whole scene changes – different colour, different trees and roadside shrubs and flowers, totally different dwellings, the metamorphosis almost as instant as when changing colour sides in a projector; each new vista bringing a grasp of delight.

Over a seemingly infinite plain of brown scrub, our road now dead straight and undulating slightly, a line of telegraph poles skirting it formed a mirage like tall buildings in the distance which deceived us until we saw it break up into parallel lines. By the road goats grazed with black and white sheep – and black-and-white sheep, the front half entirely black and the back white. Often we saw a herd crossing the road ahead, under the herdsman’s full control and very quickly between one swaying truck and the next. Stray animals are very rare but horses and mules graze by the riverbeds. The hills change to pastel greys and greens and reds with the sun almost vertically overhead soon after midday although the Peugeot’s tinted glass spoilt it rather with a blue overcast that almost eliminated the delightful pinks shades which was a pity.

An avenue of tall poplars led us into Midelt at 1.45pm – time for lunch. The cool, elegant Hotel Aichi fed us French-style and deliciously with Artichauts Vinaigrettes, then Rognons de Veau avec Champignons washed down with beer. Outside, there were vendors or gorgeous mineral stones – wherever you go, even on quite lonely roads, someone is there trying to sell you something, but pleasantly so. Midelt’s outskirts are a sad mass of litter and the rusted skeletons of cars and trucks.

Climbing the High Atlas to the Col de Tahlremt at 6250ft, we were worried slightly about the Peugeot’s thermometer, the needle rising just short of the red sector. As the bonnet was opened, the fan’s electric clutch engaged and we knew all was well. Here the villages are enclosed by walls of castellated mud, and healthy looking turkeys flutter round them. Sometimes the rock strata emerge vertically and form dorsal ridges across the hills, natural counterparts to Hadrian’s Wall. Green cultivated terraces rise from the riverbeds, often below road level, irrigated by mud-walled ditches like mighty worm casts. In the distance villages looked like heaps of children’s toy bricks, their shapes picked out in bright biscuit and black shadow by the hard sunlight. One curious rock form could have been a horizontal stack of coins on a croupier’s table; it is a geologist’s paradise, and the mineral wealth of Morocco must be almost infinite. I never thought mere rocks could be so exciting.

This was a superb day’s drive with something new to see seemingly at prearranged intervals all along the route. The Ziz Gorges (well, the river does look a bit sleepy already) are brick red with towering cathedral formations, date palms and terraced green fields by the water. Through the Gorges you suddenly look down upon a huge artificial reservoir created by dams, the water level alarmingly low for April. From a few miles short of Ksar-es-Souk and all the way to Erfoud, about 80miles, there ksour (plural of ksar = fortified village) spread along the route, legacies of fierce tribal warfare, not so very long ago, whereas Ksar-es-Souk has extensive modern military encampments. The ksour, depending on their perimeter, may have up to a dozen or so square turrets extended above the wall, and look like something straight out of Beau Geste: only Hollywood’s heroes, the cannonfire and flags were missing.

We followed the Ziz, its course bordered by luscious but painstakingly irrigated groves of date palms and fruit, into Erfoud at sunset, and stopped to photograph the stunning silhouette of a turreted Kasbah – or is it another ksar? – to the right beyond the palms. Richard was very excited about it, seeing it perhaps as a sort of curtain drop at the end of the day’s series of snaps. So he took it from all angles, at many exposures, while Mr Editor Nichols and I decided that the government-owned four-star Hotel Erfoud was probably the place to stay. Just a little along the road a sign points right to it. You guessed it – it is a splendid modern edifice built in the castellated style of a ksar – and thanks to Dick’s efforts we now had a battery of photographs to prove it.

We weren’t being so decadent in picking such a hotel: it was £6 a room, typical for a first-class hotel in any of the towns and cities outside the real tourist centres like Agadir and Marrakech. You can also rely on finding a good hotel almost everywhere you go. We weren’t quite sure why, but poor Richard had an upset stomach and tore straight off to bed with nothing more than a bottle of mineral water and a packet of clog. Mel and I sauntered downstairs to a big dinner and a couple of bottles of first-class Moroccan cabernet, a fitting end to an idyllic day’s travelling. But the Moroccan surprises weren’t yet over: no sooner had we finished eating than, drums pounding, a group of musicians and dances emerged from behind a curtain at the far end of the dining hall and set about entertaining us for the next hour or so. They were fascinating, and not long after the haunting sounds of their voices, horns, hand-claps, drums and strange banjo-like instruments had died away we headed for bed. We were, at last, on the edge of the desert and we’d found a guide called Omar who was coming at 4.30am to take us to the dunes in time for the sunrise.

Click here to read the second installmant of our 1978 Dash to the Desert adventure drive