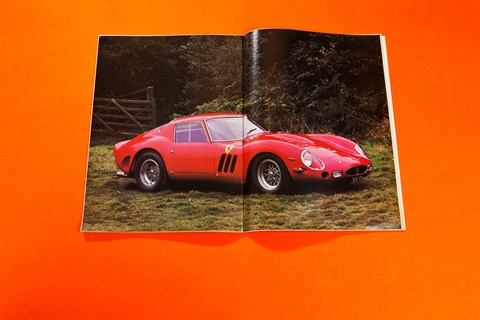

► Mel Nichols drives Ferrari 250 GTO

► Iconic car driven flat out back in ’79

► Relive the moment with CAR+

‘You’ll be tired when you get there,’ they said, grinning; and I was. But what a tiredness! Alone through the night with a Ferrari 250 GTO, blazing over 100 miles of testing and deserted roads, the exhausts whooping and snarling and barking and wailing, the engine both gentle and savage, the steering sharp and alive, the gearshift sweet and steely, the cabin cold, loud and glorious, the concentration intense; the experience fatiguing but overwhelming. And, tired or not, I couldn’t leave the car alone when I arrived. There was too much of it, too much in it, too much to be had from it. I warmed myself by the fire, ate a little and then had to go out into the night with it once more, anxious to share its extraordinary pleasures with an appreciative friend; unable simply to slip it into the garage. And nor, in the face of such inspiration, was sleep to come quickly when at last I settled down. There were too many moments to relive and too many more to anticipate; the GTO was to be mine for another six days. The legend was within my grasp at last.

For me, that legend began with a picture on a school-friend’s wall. It was a picture of a red car so beautiful and yet so purposeful that we stood in awe before it, able only to dream in our certainty that, in darkest Tasmania, we would never see one race; and nor we did. But on the Other side of the earth, in Mother England, another college boy stood awed before another red GTO as it swept to victory-one Sunday at Goodwood. He got close to it and photographed it – and dreamed about it afterwards; and the GTO was the car, he vowed, that he would, one day, do his utmost to possess.

And it was he, all these years later, who, right there at Goodwood, handed me the keys to his GTO. It was a moment heady with excitement and sombre with apprehension. I knew he’d refused £75,000 for the car only weeks before. I knew how long he’d searched for it and I knew that, when it was finally his, he’d found the car’s original number plate beneath its current, incredible 250 GTO plate and discovered, from those old photographs, that it was the self-same car that had initially captivated him at Goodwood in 1964. Dreams are rarely so felicitously fulfilled.

Nor maintained. Nick Mason, whose GTO it is, is a director of Modena Engineering, the specialist workshop setup in East Horsley, Surrey, two years ago by a group of Ferrari enthusiasts to cater exclusively for the marque: They restore Ferraris, repair them, service them and now they even sell them. When you go there, you will see bays and corridors filled with fabulous cars; and yet, when the GTO is among them, it commands special respect.

Why is the 250 GTO so special? It was the last front-engined Ferrari racing car, the crowning glory in that incredible array of gentleman’s racers, the 250 Gran Turismo Berlinettas, that, between late 1955 and 1965 won more races (three world championships among them) than any other series in history. They were the cars that did more to carve out the Ferrari reputation than any of Maranello’s other models. They were created to contest the GT category (established to separate the enclosed cars from the true sports cars in the mid- ‘50s) but some were also to be sold as road cars to customers prepared to sacrifice a few creature comforts to ultimate performance. Altogether, they were about 350 250 GTs of varying types; 36 of them were GTOs. Happily, all 36 survive, most in excellent condition and most still driven regularly.

According to Jess Purret’s superb book The Ferrari Legend: The Competition 250GT Berlinetta (John W Barnes Publishing/Patrick Stephens) the racing world in 1962 thought that, after seven indomitable years, the 250 GT was at the top of the tree. But the best was yet to come. Strong challenges were looming from the lightweight Jaguars, Aston Martin Zagatos, the Cobras and the Porsches; and Ferrari, at the end of 1960, had begun developing the GTO from the familiar low, nugget short wheelbase 250 GT (itself derived, in 1959, from the original long wheelbase GT, the car that soon after appearing in the mid ‘50s had put paid to the Mercedes 300 SL).

Ferrari knew that the 250’s engine could meet the challenge. His faith in the omnipotent Columbo-designed sohc V12 (in 3.0 litre form for the 250 – they ran in the 2.0 to 3.0 litre class) had paid off handsomely. It was sensible, simple, beautifully-made and reliable. And more power could be drawn from it without endangering that reliability: the more potent but basically similar Testa Rossa engine had also been winning races for years. The chassis was old and relatively crude but it too was sturdy and reliable and could be made to hang on for another couple of years. Importantly, since more than 100 short wheelbase cars had already been built around the chassis, the new bodywork could be used without the need for fresh homologation. And it was the bodywork that really had to change. The short wheelbase 250GT’s blunt nose limited its speed to 155mph, and beyond 149mph it grew light at the front. Nor was the short rear bodywork up to the task of keeping the rear wheels down at high speeds, and Ferrari wanted 190mph if he was to keep his growing army of opponents at bay.

Until then, Ferrari’s engineers had no concerned themselves with detail aerodynamics: their engines had always been powerful enough to overcome any drawbacks. But the puny-engined Lotuses, Panhards and Alpines at Le Mans had proved just what good aerodynamics could do. So, in 1961, with various hacked-about Berlinetta bodies, Ferrari spent a great deal of time examining penetration, drag, lift and adhesion many of the tests were conducted on the autostrada, others on the track and still more in the wind tunnel. Step-by-step, the GTO’s body evolved.

It was never really styled as such, but the final shape was and is exquisite. It’s a shape born entirely of purpose and yet that purpose has been combined with an extraordinary aesthete, a classic example of the Emilian engineers’ unique touch. Beyond admiring the shape, to look at a GTO now is to be overwhelmed: here is a racing car with chromed windscreen wiper arms and chromed surrounds for its windscreen, backlight and side windows, the most marvellous chromed clips to hold its forward-opening bonnet in place (along with those little leather straps), locking door catches, beautiful hand-beaten surrounds for its headlight covers and a delicate horse carved from light alloy mounted so as to float in it elliptical snout, itself outlined with chrome. There were slight variations to the GTO bodies, but most of them were like Nick’s car (chassis no 3757GT, delivered to the Belgian Ecurie Francorchamps on June 14, 1962) with rectangular fog-lights set into the nose either side of the central opening, then the twin brake duct openings and with the sidelights jutting from the curving bodywork half under and half beside the headlights. And then there were the three extra vents in the nose, the three scallops that spelled out GTO to the world. You undid their press-and-twist Zuz fasteners and lifted off the covers to increase the cooling at low speeds. There were, too, those plexiglass scoops over the inlets on the cowl that fed air to the cockpit, and the slashes in the flanks that released the air fed to the brakes (the forward vent) and air from the engine compartment (the after vent). All the GTOs came out of the factory with just these two side vents, but many owners swiftly added a fashionable third. Ecurie Francorchamps did.

There was another vent in each rear mudguard-to release air from the rear brakes, and on the tail there was, for the first time on a GT car, a spoiler. Initially, the spoiler was riveted on. Later, it was faired into the bodywork. All of these things were distinctively GTO; but most of all it was a car with a very low-nose and low waistline, and it had all the penetration that would allow a 22201b car of only 3.01itres to reach 180mph.

The engine’s height helped there. For its new role it was given a new dry sump made of magnesium, which not only helped the lubrication but meant that the engine’s height was extremely modest, permitting the low nose and bonnet line and helping the engineers obtain the lowest possible centre of gravity. The V12, its block cast in silumin with the cylinder banks at 60deg, was made to extremely close tolerances with enormous skill. The crank was, in familiar Ferrari fashion, machined from one steel billet; but so too were the con rods. The cylinder heads had the biggest valves the combustion chambers could take, and all the gas conduits were beautifully polished, with each intake/exhaust port matched against the other. The rocker arms were milled for spring clearance and they pivoted on needle bearings. The cam covers were magnesium, again to save weight. Nestling between them went six twin-choke downdraught Webers topped only with stubby tittle trumpets with their flanges carefully siamesed. The precise capacity, from an over-square bore and stroke of 73 x 58.8mm, was 2953cc. The compression ratio was 9.8 to one, and if each engine did not develop between 296 and 302bhp at 7500rpm on the test bed it went back-to the racing shop for rebuilding. Only when the required figures were registered and the engine fully tested was it installed in the car. Coupled to it went an all-synchromesh five-speed gearbox and any one of eight differentials ranging from a low of4.85 to one (which gave phenomenal acceleration against a top speed of 129.3mph at 7500rpm in fifth) to a high of 3.5 to one (which meant less acceleration but a top speed of 175.9mph). It was enough, when the GTO began racing at the beginning of the 1962 season, to devastate the opposition.

The chassis of the GTO was very similar to that of the old 250 GT. The 94.4in wheelbase was retained, and the frame was made up from the same sort of tubular steel although some of the tubing itself and the position of many of the bracing members and mounts for things like the body, fuel-tank, Watts linkages and dampers was different. There were forged unequal length A-arms, coil springs and new adjustable Koni dampers at the front, along with a hefty anti-roll bar. The rear axle was live, located with stiffer leaf springs than have been used before, and by four track rods, the two Watts links and another pair of the new Koni shockers. There were disc brakes all round, with special alloy callipers at the front and a little pump to boost the braking effort to the front wheels. The steering was 17 to one ZF recirculating ball. The 35gal fuel tank, hand-riveted, went behind the rear axle: the 5gal oil reservoir was between the chassis rails just behind the passenger’s seat. Both were protected from stones-by an aluminium shield slung beneath the car that was also cunningly contrived to use the air flow beneath the car to assist high-speed stability. The wheels were Borrani, with alloy rims and steel spokes, 600 x 1 5 at the front and 700x 15 at the rear carrying either Dunlop R5s or R6s. Those tyres would last 9hours at Le Mans and 1.5hours at Goodwood.

It was a crisp, clear afternoon at Goodwood this winter when it became my turn to open the door of a GTO, drop into the little leather bucket and snap on the racing harness: The door, you note, feels light and almost dainty and yet it shuts with a no nonsense thunk. There is no more flab on it than there is elsewhere in the cabin. There isn’t even a door handle inside, only a cord to be pulled when you wish to get out again. Your eyes pick up plenty of the black-painted tubing of the frame work: in the foot-wells, running up inside the pillars, close beside your seat, and even diagonally across the passenger’s foot space, forcing one shin to go under it-and one to go over it. The plain tunnel that splits the cockpit has flat sides and top. On its left side there is a little leather-covered pad, a buffer for the driver’s right knee. From the top of the tunnel juts the box holding the gearlever and its gate: big, meaty, meaningful beautiful. The lever itself rises high, so that its round, glistening alloy knob is almost at the level of the steering wheel boss — or, for someone my height (5ft 11in) at a point that allows the arm to be run almost straight out from the shoulder. In first it is less than a hand’s spread from the wheel rim; in fourth, where it is furthest from you, it is at a full arm’s stretch and around 120deg to the plane of the chest. The wheel has even more appeal. Straight ahead of you, polished wood bonded to an alloy rim and with alloy spokes and, dancing in its centre, the black-on-yellow horse.

Your hands drop on to it perfectly, not quite at full arm’s reach. Through it, mounted in a frugal black crackle-covered metal panel that is shrouded no more than it need be, you see a huge, clear tachometer-that reads to 10,000rpm. Its tell-tale is set at 7500rpm. Around it there are five smaller dials: on the far left the fuel gauge, at 11 0’clock to the tachometer the fuel pressure gauge and at seven the water temperature gauge. The oil pressure gauge is beside the upper right side of the tachometer, and the oil temperature gauge is directly below that. It is a neat grouping, each dial nicely chrome-rimmed, and all but free from reflections. There is an indicator stalk (from a Lancia Fulvia, one suspects) on the left of the steering column. Arrayed across a thin little panel tacked on to the ma-n dash cowling to the right of the wheel you find the tiny ignition lock, the knurled headlight knob and then three tiny alloy toggles. The nearest to you is to switch the fuel pumps on and off, and next the wipers and the next the fog-lights. Finally, there is another knurled knob with which you adjust your panel lighting. There is a wide slot cut into the centre of the main dash cowling. Through it peep three pipes; they provide the demisting and the ventilation. You can supplement them on a hot day by tugging back the sliding plexiglass panels that form the side windows. The air is swept from the cabin through a hole — shielded by another of those plastic scoops you find on the bonnet— in the rear window which is itself plexiglass.

Lift your eyes beyond the dashboard and the view is exquisite. It is rather akin to looking down an E-type’s bonnet but it is shorter and the curves more sultry (though not as pronounced as those of the D-type). There is the seductive curve of the wing on flattening out low and smooth ahead of the windscreen to disappear below the point where your left hand rests on the wheel. Were you to guide the car close alongside a white line, the wing would curve out over it at the front but it would become visible again where you glance down through the lower corner of the windscreen— voluptuous curves or not, the GTO can be placed tight, tight, tight into a curb because it provides its driver with tremendously good vision. Swing the eyes across to the centre of the car and there is a flat section and then the bulge that covers those six carburettors. Another flat section and then the full curve of the right wing. The Perspex scoops and the chromed bonnet clips, gleaming in the sun, are the icing on the cake. Does this car look menacingly beautiful from the outside? From inside, it is merely sensational.

Adjust the mirror, squeeze down on the throttle, turn the key in its neat lock and then push it. There is a wheeze and then the roar; this engine has the lightest of flywheels and the most precise of throttle linkages. You’ve pressed too hard and the revs are soaring. Now you know about its responsiveness, at least. Pull the tall lever over and back into first, and feel the gear engage. Ease the clutch out; how extraordinarily sweet and accommodating it is. The GTO rolls forward, bumping across the grass, jiggling and joggling; what will it be like on those long, difficult roads away from the circuit, this car that ran third at Le Mans in 1962, won at Spa in the 500km race in 1963 and set a new lap record of 127mph doing it, and then went on and on with its race record? Didn’t Jess Pourret say he’d driven 25,000 absolutely trouble free miles on the road in his GTO; and didn’t Nick Mason’s little logbook list journeys he’d made in his 18months with the car as diverse as a run to the Nurburgring for a historical meeting and taking his daughter the 2miles to school through north London streets?

The GTO was quite warm. It had been running hard around Goodwood all afternoon. Modena Engineering and some of their friends were having one of their owners’ days. The car swung on to the track, empty now since most people had packed up and gone, and began accelerating. Clean, hard — and loud. All the legendary sounds of the 12 were there: the solid suck of the carburettors, the whine and thrash of the cams and the valve gear and a constantly changing exhaust note that sounds more marvellous than one might think has any right to come from a mechanical object. The first shift left me in no doubt about the pleasures that were going to come from that gearlever and -its big, slotted gate. And the steering, into the first bend, swiftly showed that it, too, had more than enough to offer. It was quite light, quick, full Of feel and there was no doubt that the car would react to it very swiftly and accurately. There was the slightest understeer, and then, in response to a little more from the engine when I

cared to ask for it with my toes, a swift shift to neutrality. Moments, mere moments, were enough to demonstrate the integrity and balance of the car, so exciting and dramatic and yet so comforting and reassuring to drive (until, says David Piper, who raced GTOs often, you sought the last half-second and then it could become very difficult, prone to sudden breakaway that was difficult to catch). It was soon apparent that all the performance could be used; and how glorious it was to hear the engine howl around — so quickly! — to 7500 in fourth, those exhausts thundering out their music, and then get that stupendous change of note with the shift, flat, into fifth.

Running hard like that, climbing beyond 7000rpm and 140mph in top but unable for the sake of early preserve to carry right on to the 7500rpm maximum and the 147mph it would bring, there was still nothing intimidating or difficult about the GTO It just went lunging, yowling, forward; light and easy in the hands, rock stable, lifting very slightly at the front but stuck down hard at the rear. You knew it was stuck down hard; you could feel it through your backside. Then it was time for the brakes, and they required a strong, sustained shove, the leg straining against the pedal and the’ results modest. So that was it: allow plenty of space, more than you would-in almost any contemporary car and then push hard with the ball of the foot, dabbing at the throttle with the smaller toes for the downshifts. The stability was all still there, and when the foot came off the brake the car just turned perfectly into the bend and went sailing through and away to go up through the gears again. In a few more laps; when it had demonstrated its poise, I was able to begin drifting it, and it was there that it was sufficiently delectable to make me tingle with pleasure. That link between the backside and the rear axle said everything: the tyres shifted sideways and you could feel them nudging across the surface. Flick the wooden wheel and they came straight back, and with a superb tidiness. There was so much purpose to it all but so much feel arid character too, and within those few laps the car had -me firmly within its spell.

Out on the road, it was no less captivating. The ride was very firm and ever-joggly and it would, as the Modena Engineering people knowingly (enviously!) had said as they saw me off, undoubtedly tire me by the time I’d completed the 150mile journey that lay ahead. From time to time, the racing tyres made the car tug against the wheel and dart about. But it was not unexpected and never awkward: just part of driving a racing car of another period on the road: It had, more than anything else, the highly animated feel of a race car going slowly. The motion wasn’t exactly discordant but all the ingredients were not flowing silkily, perfectly, together, to create the optimum. And there was great pleasure to be had from driving the car slowly like that, feeling and examining ail those ingredients, savouring each, and occasionally blending them with a concerted blast through an inviting series of bends or with full acceleration past slower traffic.

It wasn’t long before I was in thick traffic, for my journey was taking me right through London, and-any fears I might once have harboured about the G TO’s behaviour there were despatched at a stroke. That smooth and positive clutch was never anything else that potent VI 2 demonstrated that its heart was as big as its soul, moving off without fuss and rolling along in the snarls without a moment’s hesitation or complaint. It would, if you cared to test its flexibility, potter down to 1000rpm — 20mph — in fifth and pick up happily again. Drive the GTO in the city? Yes; absolutely

Ah, but how extraordinarily satisfying it is to drive beyond the conurbation. By the time I’d cleared London again there was little traffic left on the roads and I was ready to string those GTO ingredients together as best I could. To hear the sound and revel in the acceleration — it’s quite subjective without a speedo, but I would guess that it’s about Countach level: enough to press you hard back into the seat — caused me to run to 7500rpm in the gears as often as I could. Fifty, 74, 101 and 126mph, with 5th to come. Clear roundabouts challenged me to get the braking exact, to match the downshifts perfectly, to select the correct line and then to take the Ferrari through, wailing hard and balanced on the edge of a drift. Mild though the angles were, you could feel it heeling slightly, nose lifting and tail dipping, with the power. Sometimes, sweeping out of the final curve with the VI 2 giving its all, the tail would nudge quickly and yet somehow gently into flat, positive oversteer. How intense and how beautiful the feeling when, to catch it, you simply flicked the wrists, with the wheel light and delicate between the fingers! On smooth roads, when you’ve gotten it right, the GTO is like that: possessed of the poise and the balance special to a terribly good front-engined car. If it tugged against the wheel and jiggled at loping speeds on the back-roads that quickly followed the dual carriageways, it sharpened into a clean, flowing projectile beyond 100mph — and even on those roads that was so often possible with such lightning acceleration available. Everything flowed together to attain the objective of covering the ground quickly, effectively and securely. ft just ran straight and hard, but still with all that communication pouring through. Under hard brakes into the tighter bends it did not dodge and dart as one might expect a car of its age and type to do; its approach was smooth and sure. Nor was it much deflected by bumps mid-bend, and if I wanted the slightest response or the slightest reduction -in power from the engine to adjust the line or attitude, had it. The steering was the same. There was the slightest possible leeway, common to such recirculating ball steering, at the rim in the straight ahead position, but more than a fraction of an inch and you had instant but fluid action. Those lingering, sensuous gearshifts of the miles in town became swift purposeful movements, the hand helped by near perfect spring loading, the clutch ideal for in-an-out jabs. And there was that furious noise all the time — from the carburettors and the cams, from the exhausts and from the wind. Near the limit, the roar of the wind past the little Perspex side windows was like that of a modern fighter flying fast at medium height. Cold air rushed in between those Perspex panels and from between the doors and the wings, for there are no niceties like rubber seals. Nor was the heater, simple as it is, working and t shivered when I had time as I trundled respectfully and laboriously through the villages, thankful that it wasn’t raining. The GTO would not be so much fun then.

So – cold, tired by the noise, the liveliness of the ride and the degree of concentration, but exalted by the experience— I arrived at my destination to be greeted by friends who, from within their house, had heard the GTO coming through the night. I drove it again later that night, unable to tear myself away from its remarkable character; and in the ensuing days I drove it whenever I could. Any excuse was enough; taking a child to the church fete, nipping down to the butchers, volunteering to go and pick up the bread, insisting that a far-flung antique dealer had a piece worth inspecting, grumbling falsely that a certain beer was unavailable in any but an off-licence 30miIes away. Each time, the GTO fired perfectly from cold in response to three prods of the throttle, and then idled without fuss. It would take a long time to warm up, and the gearbox was slightly stiff until it did, but according it that time and appropriately respectful treatment was just part of the pleasure of being with it. So too was to roll gently through the higgledy-piggeldy villages, listening to the noise coming back off the walls, or to be caught in a stream of traffic, having to meander up and down the lower part of the rev range, soaking up the constantly varying sounds. There would be a pronounced burble up to 2000rpm before the sound grew sharper and shriller, rising through a proper tearing calico’ period around 3500rpm. In the higher gears you could feel the engine climb properly onto the cams at that point, but proper peakiness was not part of its behaviour and nor was hesitancy. Just a mild caress of the throttle would have the car surging forward. Should you have cause to back off without being able to wind the engine right out, there’d be a tremendous rumble on the over-run, laced with a sort of crackling and popping, in the range between 3500 and 4000rpm. From the cams here would come a really shrill whine. Accelerate again and that whine would rise until it became a solid, exciting thrash. The exhaust note would be rising too, and about 5000rpm combine with the engine noise to create the real bellow that, by the time you’d reached 7500rpm, had become so beautiful it was hard to believe. Once, while Richard Davies and Adam Stinson were up from London to photograph the GTO, I went off some distance to check a new location. t was able, through miles of quiet forest on the way back, to run the car right out flat and then, as I approached the intersection they were near, come right down through the gearbox. Adam, who is new to cars and had never heard a 12 before, let alone one this magnificent, was moved to say that if you were asked to imagine how the world’s best racing car would sound— perfect, powerful, magnificent — then you would imagine something like this.

Were you to establish an image of classical handling, you would probably find that the GTO fitted it-perfectly too. Savour its cornering power and balance though I might, I never felt I had fully extended the car; I knew it to have finite balance well beyond me. And yet it never treated me with cruelty or even disdain. Once, coming sufficiently hard through a 100mph bend for all of the road and careful balancing of throttle and steering to be necessary, I encountered a mole right where, in an instant, the GTO’s left front wheel would be. There was a moment of pity and panic but then somehow I knew I could drive around him, and the car allowed me to do it. Once, almost flat in second and pushed hard back into the little leather bucket by the power, I encountered a patch of mud on a normally safe crest and the tail snapped around far enough for me to look, wide-eyed, out the side window. At 70mph and straddling the road, the car allowed me to collect it cleanly and more easily than I might dared have hoped. What it had done was to remind me that, gentle though it was prepared to be (‘It always feels as if it’s on your side,’ Nick had said. ‘That’s why it’s so special’), those

300horses were alive and very well. Beyond relating that knowledge to the prevailing conditions, and beyond allowing something like double the braking distances one would in a modern high-performance car, the GTO insists on nothing from its driver; but he is not doing it justice if he does not try to perform every function as perfectly as he is able. It feels old, a survivor of a previous era, but it rises way beyond that era and mechanical limitations like a live axle and leaf springs too. As a car of its time and type it is everything, to relate it to Mr Setright’s piece that the Cobra is not.

Sorrowfully, on the 6th day, I took the GTO from the garage for the last time and, heading south once more, ran it hard where I knew I could run it hard and trundled with only minimally reduced pleasure where I had to trundle. Just to be in the car, feeling it and hearing it, was to be enthralled. In London, I picked up Sub Editor Murray for the final run down to Modena Engineering, and like everyone else who rode in the car he too was reduced to speechless awe, when, clearing town, I let it all go for the last time. He will, no doubt, ride in faster cars; and among those I have been privileged to savour have been many that, given the benefits of many more years of progress in tyres and suspension (let alone mid-engined layout), will corner more quickly and more securely, and cover bumpy roads in significantly less time and greater comfort. But I have never driven a car in which the ingredients blend quite so sumptuously to provide the driver with enormous pools of pleasure in which to wallow, a car where purpose is backed by even greater degrees of soul and character; yes, and manners too. Do not, however, think of the GTO as a servile car. It is a proud and truly wonderful machine, the Ferrari epitomised, and the six days I spent with it have enriched my treasure trove of motoring pleasures beyond my dreams.

Ferrari country

Fast roads bring out the best in the GTO, and for the driver the experience is exquisite. Stability is demonstrably good and even cornering hard, as the GTO is in this picture, it rolls very little. Handling at times like this is superb, helped by impeccable engine response. Cabin is a workplace with real appeal: leather, alloy, wood and black crackle. Low waist and big screen mean good vision

The distinctive snout of the Ferrari 250GTO allowed Maranello to increase top speed of their Gran Turismo racers from 155 to almost 180mph. Big vents below lights feed brakes. Taking caps off three unique vents above main opening increases flow to radiator in hot weather. Similar flap further up hides radiator cap. Engine is quite rightly considered one of the finest — sohc 3.01itre VI 2 at 60deg, six Webers, 300bhp at 7500rpm