► Celebrating 50 years of V12 Lamborghinis

► From the sublime Miura, Countach, and Diablo…

► … to the sensational Murcielago and Aventador

When you Drive a Lamborghini Aventador SV the world stops – seven hundred and forty horsepower and a sound like a Lexus LFA and a Shelby Cobra duetting on a Black Keys cover can do that. Drive an SV slowly and little boys with messy hair and much older ones with none at all will freeze, rooted to the spot, and stare open-mouthed. Drive an SV fast and cars heading in the same direction but obediently kowtowing to the 70mph speed limit smear past the window like a streak of raindrops. And you do drive it fast; it’s impossible not to. Think you’ll be able to keep it under 100mph and avoid sending your licence on an enforced sabbatical? Forget it. Try one-forty. Minimum. The SV’ll get there so quickly you’ll find yourself indulging again and again, seeking out those spaces where you’re convinced you won’t get caught, but where common sense would say you quite possibly would. Resistance is futile so press the pedal, live for the moment – every moment – and soak up a sound mankind will soon only hear in grainy bootleg recordings passed down from their grandfathers. You can worry about the roadblock when you get there.

Except for tobacco, it’s difficult to think of many things so capable of delivering joy while being simultaneously so out of step with the zeitgeist as the Aventador SV. Thirsty, polluting, antisocially overpowered and dangerously fast in the wrong hands, a V12 Lamborghini is the crystallisation of why you first loved cars all those years ago, and why you still do. A blend of classic supercar charm and modern tech, Lamborghini’s most extreme production Aventador is a worthy recipient of the fabled Super Veloce badge. But is it the best Lambo ever?

One look at the Miura is enough to fill you with doubt. But one look is never enough – you can’t take your eyes off a Miura. It’s a tiny car in the metal; 86mm lower even than the Aventador, as beautiful and delicate as a spider’s web, and a complete anomaly. Every other car we’ve gathered here plays by the accepted Lambo rules of supercar design: the slide rules. They’re angular and angry. But the Miura is soft, curvaceous, warm, sensual. If it were a Bond girl it’d be Thunderball’s Claudine Auger to the Countach’s Grace Jones. If it was a bond it’d be one you really ought to have kept hold of: prices have gone stratospheric in the last 10 years. This one, just restored by marque specialist Colin Clarke (colinclarkeengineering.co.uk) is worth over £1.5m.

That value is as much to do with the Miura’s significance as its ethereal beauty. You know the story: successful industrialist gets sick of his unreliable Ferrari, rows with the boss, claims he can do better, and creates his own cross-town car company to do exactly that. He starts with a bug-eyed GT with an engine commissioned by disgruntled ex-Ferrari man Bizzarrini, then turns the world inside out with the mid-engined Miura. Presento, il supercar!

Technically, the Miura’s a bit of an oddball. It’s constructed of steel rather than aluminium and the V12 engine, though lifted from the earlier 400GT, isn’t merely mounted 6ft further back but but twisted through 90 degrees and mounted on top of the transmission, just like BMC’s ’59 Mini.

The first slim-hipped P400 cars (P for posterior, or rear; 4 for 4.0) produced 345bhp, later bumped to 365bhp for the 1968 P400S. But barring the one-off Jota, a stillborn track-ready offshoot and its handful of SVJ-badged imitators, it’s the 1971 SV, the car we’re driving, that’s the ultimate incarnation of the Miura. That was the first outing for Lamborghini’s now familiar Super Veloce name, back then not a standalone model, merely an evolutionary step, but a hugely more serious Lamborghini all the same. Fat arches covered wider but still plump-walled rubber, the earlier car’s effete headlamp eyebrows gone and the V12 teased to produce 380bhp.

Approach the Miura’s driver’s door and the car appears to shrink with each step, the roofline apparently at waist height and the push-button door release so low, hidden below the lowest of those gorgeous slats, that it’s like trying to operate one of those wheelchair-accessible ATMs. Open the door and the slats come too. As a piece of design theatre it’s not as outlandish as the Countach’s scissor doors, but it’s an interesting touch, appreciated best from the front with both doors open: you’re presented with the view of a raging bull, horns and all.

The view from the other side of the glass is every bit as cool, the windscreen pillars so vestigial you feel like you’ve got trinocular vision when you drop into the recumbent seats. There’s little in the way of dashboard beyond the aircraft-themed console looming over the open-gated shifter, its six small gauges supplementing the two main clocks that seem to float in the ether ahead of you.

Twist the key (no starter button here, they were for uncouth racers) and instead of the grandstanding roar you’re expecting the V12 gently, almost apologetically bumbles into life. The thin-rimmed steering wheel points skywards like an Area 51 satellite dish trying to intercept alien chatter, but the steering itself shrugs off its heft once you’ve eased the heavy clutch pedal out, wowing with delicacy and communication that you didn’t expect, nudging your wrists up and down as the front tyres feel their way along the road.

There’s no redline on the Jaeger rev counter but in deference to this car’s freshly rebuilt motor I stick to 5000rpm, which is about 500rpm after the V12 really starts to get into its stride. The noise is immense under load, impossibly so by modern standards, a thundering wail of valvetrain, gear noise and induction roar from the brace of carbs sitting behind your head. But it’s more than bluster. Even just dipping a toe into the meat of the powerband, this Miura feels rapid. Contemporary tests put the 0-62mph time at 6sec and the top speed at around 170mph – ample go given the feeble brakes imbue it with the stopping performance of an Australian road train.

Charming it certainly is, but challenging too. You want to be able to flick it around like a Ferrari Dino but you’d need both skill and bravery to really paste a Miura because by any objective yardstick it is miles less capable as a driver’s car than its wedgy successor.

The Countach is a very different beast to the Miura. Harder to get into, harder to see out of, but much easier to send down the road in something like the same manner in which you’d approach the 200+mph Aventador. And so what if the claimed 200mph top speed for the original show car was pure bull? To a nation tucking into the terminally tedious new Morris Marina in 1971, the car Ferruccio unveiled at that year’s Geneva Expo looked more than capable. Though again designed by Marcello Gandini – and borrowing heavily from his stunning 1968 Alfa Carabo concept – the LP500 prototype’s crisp sheet metal and outrageous scissor doors broke all links with the swoopy Miura, and it was the same story underneath the skin. The chassis was now a steel spaceframe, and the V12 turned through another 90 degrees – Longitudinale Posteriore – but with the transmission tucked under the tunnel facing forwards, unlike most mid-engined cars.

The early 365bhp LP400 production cars – narrow of body, wobbly of chassis and now worth a mil – might be closest to Gandini’s blueprints but it’s cars like this black LP500, all arch flares, deep-dish rims and arrow-shaped spoiler, that most minds conjure when hearing the word Countach. The 1978 LP400S was first to get those mods, but ironically it mated them to a 20bhp meeker V12, a flaw remedied on 1982’s LP500S when a hike to 4.8 litres returned power to the original’s 365. This is the Countach as I remember seeing it for the first time. Big, ballsy and ready to give any Ferrari a black eye. Then, 30 years ago, it was hunkered down on a grimy moorland road in the pages of CAR. Today it’s here and the keys are in my hand.

As with the Miura, you’ve still got an offset pedal box and limited seat adjustment to deal with, but this time the steering wheel is set at an angle that suggests humans were consulted during development. But it still feels like a Lamborghini. Flat windscreen. No indication where the nose is. Slightly scary. And I haven’t even fired the thing up. Bloody terrifying once I do. If Jeffrey Dahmer sang in the shower, it probably sounded like this.

It’s not that friendly to drive either, at least not at first. The controls are heavy – even on the move the steering is weightier than the Miura’s, the gear change stiff – but the chassis is so much better balanced. The Miura might have been the first supercar, but the Countach is the first that looked and drove like one in the modern sense. The Aventador is about as demanding as a Kia Picanto in comparison, but you can sense the shared DNA between Lamborghini’s second supercar and its latest, even if it’s more philosophical than technical.

And even if it doesn’t have the sledgehammer kick of the later QV, this 500S (or 5000S as it’s sometimes called) pulls impressively hard for an old timer, pushing you deep into that strange buttoned therapist’s couch that passes for a driver’s seat, the claustrophobic cabin reverberating with a mix of exhaust beat and the voracious slurping of six twin-choke carbs. Period tests told of 5.6sec to 60mph and 170+mph top speeds without the optional wing, which held it back by 10mph. Most buyers bought it anyway, and kept buying the Countach long after its original Ferrari Boxer nemesis had given way to the Testarossa. Constant evolution was the key, the final four-valves-per-cylinder 5.2 Quattrovalvole iteration delivering a mighty 450bhp – monstrous power for the time.

By 1990 though, the Countach’s time was up. And so was Lamborghini’s patience with Gandini. Sticking with tradition, Lamborghini had again asked Marcello to draw its next supercar but new boss Chrysler didn’t like the result, judging it too fussy, and reworked the design. The Diablo’s raw materials weren’t that different from those of the Countach, but that V12 was boosted to 5.7 litres and 492bhp for a 202mph top speed.

A four-wheel drive VT arrived in 1993, and then, more than 20 years after bowing out, the SV badge made a return in 1995. This time it was a standalone model; more dynamic than the standard car and – incredibly – for less money, something unthinkable in modern times. With more power and rear-wheel drive (rather than the four-wheel drive of the VT), it was lighter and faster. But it wasn’t the most unhinged Diablo. Among pre-facelift cars (recognisable by their pop-up lamps), the SE30 and its track-ready Jota were even fiercer. And the ultimate post-’99 cars have to be the limited run of 80 Diablo GTs.

Even in the context of the current Aventador SV, the GT is an evil-looking machine. There’s something disquieting about it; the wider wings covering those three-piece OZ rims, the huge bonnet vent, that monstrous rear diffuser. When the engine’s running your conscious of not getting too close to the giant roof snorkel – just in case the 6.0 V12 snorts you down whole.

Stretched to 6.0-litres and delivering its 575bhp exclusively to the rear wheels, this example is running straight-through pipes: they simply hold the door open as a stampede of V12 noise charges through from the exhaust ports. In an era where we’ve almost convinced ourselves that the dull blare of turbocharged engines is worth listening to, here’s the real deal to set us straight.

It’s tempting to dismiss the Diablo as the album filler between the classics and the modern stuff. The reality – at least when it comes to these later models, if not the underdeveloped originals – is much better. After the cramped Countach, the Diablo, with its strangely drooping window line, feels bright inside, the GT’s gorgeous carbon-backed buckets locking you in pace in front of the leather-wrapped, alcantara-bossed wheel. Compared to the Countach I’ve just stepped from, the addition of power steering transforms the driving experience. Low speed manoeuvrability feels less like a Foreign Legion fitness test, and the extra lightness at higher speeds makes it so much easier to flick the Diablo about on the move, heightening the palpable sense of agility. Yet despite that assistance, there’s still feedback aplenty, the wheel gently wriggling in your hands, and sufficient traction from the 335mm rear rubber not to worry about that 575bhp. This car is the surprise of the day. I’ve driven a GT before but this one is even better than I remember, a brilliantly judged blend of classic old school Lamborghini scariness and modern usability.

But not genuinely modern technology. That didn’t really come until two generations later, and the arrival of the Aventador in 2011. Although the Murcielago, the car that followed the Diablo, and today’s Aventador might look outwardly similar, they’re totally different beasts beneath the skin. Where the Murcielago follows the Countach’s lead, hiding a steel spaceframe chassis beneath its skin, the Aventador is built around a carbonfibre monocell. Where the Murcielago uses an evolution of Bizzarrini’s four-decade-old V12, its successor’s V12 is genuinely all-new, a screaming short-stroke motor worth 690bhp in standard form and stretched to 740bhp for the SV. Instead of conventional coil-sprung suspension, the latest Lambo uses racing-style inboard pushrod dampers.

Does it sound like we’re in danger of overlooking the Murcielago’s huge contribution to Lamborghini’s supercar history? That wouldn’t be fair. The Murcie brought carbonfibre brakes and the hugely popular e-gear paddleshift transmission to Lamborghini’s V12 supercar, and with Audi bums now firmly on the boardroom seats at Sant’Agata, quality was miles better too.

The greatest fear was that Audi’s steadying hand would erode Lamborghini’s character, but a drive in any Murcielago, and in particular the SV – the greatest of the lot – proves those fears totally unfounded. In its swansong outing the venerable V12, by now 6.2 litres and 661bhp, is an absolute behemoth. Noisy, raw and filling the cabin with more good vibrations than a mindfulness self-help CD, that V12 dominates the driving experience, intimidating the newcomer with its aural fireworks as the rev counter needle swings through the first half of its arc, then knocking the wind clean out of your lungs as it lunges for 8000rpm.

Sixty-two takes 3.0sec, compared to 3.4sec in the standard LP640, but the top speed fell from 211mph to 209mph – or climbed to 212mph with the smaller standard wing. Even without the big spoiler and its exquisite struts, there’s no mistaking the SV for a lesser Lambo: blackout composite aero parts feature front, back and side, along with a black coating for the wheels – at 18in tiny in diameter, if not in width.

What you can’t see is that Lamborghini had ditched 100kg of kerb weight with those changes, or how special they make it to drive, how much sweeter thesteering is, or how strong those carbon brakes are. But neither can they tell you how much better the Aventador SV is than even that. So we’ll do it for you.

There’s no mistaking the step-change. The new-gen V12 engine is so much smoother, revs flaring with the merest brush of the throttle, and it makes the whole car feel like it is without inertia, a sensation that the older cars can’t match. Fat pillars impede your view and the seats feel like they’re fashioned from slabs of granite. But get the SV rolling and it’s a revelation. Not supple, despite the adaptive dampers lesser Aventadors so desperately need, but nimble, flickable, and incredibly benign. Although it retains a four-wheel-drive layout, there’s so much less understeer than in the Murcielago, and nothing nasty to catch you out should you get the other end slipping and let it get out of hand. The thing’s a pussycat in a tiger’s skin, a serial killer with the manners of a kindly vicar, resolutely secure on the road, but more than happy to let you tease the grip on track. No V12 Lambo supercar in the type’s 50-year history has been so entertaining, so forgiving. And even if you haven’t got the driving skills of Pirelli test driver Marco Mapelli, you can still sense how he was able to pull off a 6min 57sec lap of the Nürburgring.

Does that make it the greatest Lamborghini? It’s certainly the most dynamically able, but perhaps there’s more to it than that. A Lamborghini is such an irrational thing that its competence is almost an adjunct to its base emotional draw. Which you’d grab the keys for first might well rest on the generation to which you belong, which poster you had on your wall, whether your favourite film was The Italian Job, Cannonball Run or, er The First Wives Club (Diablo fans really suffered for a fix). But over 40 years after it was launched, the Countach retains something truly rare in the car world, a true cross-generational appeal. It’s the origin of the supercar as we know it, and in our eyes the greatest Lamborghini of them all.

Miura

Number built: 764 (1966-1973)

Price then: £10,760 (P400 S)

Value now: £1million and beyond…

Same Bizzarrini-designed V12 as the front-engined 400GT, but this time mounted behind the seats, transversely, on top of the gearbox, and fitted with four-triple-choke Webers, not six twins. Quite pretty steel body designed by Marcello Gandini at Bertone. All were coupes apart from one-off Roadster concept produced by Bertone in 1968, and a roofless SVJ converted years later for then boss Patrick Mimran. Steel monocoque chassis by Gian Paolo Dallara with input from Paolo Stanzini and Bob Wallace. Some suspension shared with 400GT to reduce costs.

Engine (SV): 3929cc 24v V12, 380bhp @ 7850rpm, 295lb ft @ 5750rpm

Performance: 6.5sec 0-62mph, 175mph

Weight: 1245kg

Length/width/height: 4390/1780/1050mm

CAR said then: ‘A supremely glamorous, beautifully engineered toy with which rich men might indulge themselves in the innocent and increasingly undervalued art of recreational driving’

Verdict now: The most beautiful supercar of all time, if not the best to drive

Rating: ****

Countach

Number built: 2049 (1974-1990)

Price then: £18,000 (1975)

Value now: £1million

The V12 switches to a north-south orientation but with the gearbox under tunnel, nearest driver. Reverts to six twin-choke sidedraught carbs initially, then downdraughts for QV necessitating huge bulge in engine lid. For the chassis Lamborghini switched to a competition-style steel spaceframe for Countach. It proved weak on early cars leading to disappointing handling. Pirelli’s revolutionary square-jawed P7 tyre brought a whole new look on LP400S. Bodywork – alloy panels on that steel spaceframe – was again by Gandini. It needed big cooling ducts adding to the show car’s rear quarters to work. Early cars wore no arch extensions or wings – that lot came with 1978’s LP400S poster boy.

Engine (LP500S): 4754cc 24v V12, 370bhp @ 7000rpm, 302lb ft @ 4500rpm

Performance: 5.6sec 0-62mph, 170mph

Weight: 1490kg

Length/width/height: 4140/2000/1070mm

CAR said then: ‘For sheer outlandish eye appeal, and track-car capability that’s translatable for the road, there is simply no better car‘

Verdict now: As good to drive as that Athena poster promised

Rating: *****

Diablo

Number built: 2884 (1990-2001)

Price then: £155,000

Value now: £160,000

The V12 is upped to 5.7 litres initially and fitted with four-valve heads and multipoint fuel injection. Final cars boosted to 6.0 litres as Audi prepared to launch Murcielago. Four-wheel drive from 1993. Chassis is still a steel spaceframe mounting double-wishbone coil spring suspension with front and rear anti-roll bars, like Countach, but switches from round to square tubes for simpler construction, and high-strength steel is added to the cockpit. Bicep-busting unassisted steering until ’93. Aluminium and composite body is based on another Gandini design but was substantially softened at new boss Chrysler’s insistence by American stylist Tom Gale, later of Plymouth Prowler and Dodge Viper fame.

Engine (GT): 5992cc 48v V12, 575bhp @ 7300rpm, 465lb ft @ 5500rpm

Performance: 3.9sec 0-62mph, 210mph

Weight: 1460kg

Length/width/height: 4430/2040/1115mm

CAR said then: ‘It isn’t nearly as vicious as the Countach but it still calls for skill and respect’

Verdict now: The bridge between V12 Lamborghinis old and new is driveable and deranged

Rating: *****

Murcielago

Number built: 4099 (2001-2010)

Price then: £160,000

Value now: £120,000 (£350k for SV)

The V12 gains a dry sump, a drive-by-wire throttle and another stretch to 6.2-litres and 572bhp for first Murcie, then 631bhp and 6.5 litres for the LP640. Slick new gearbox has H-pattern and sixth ratio. E-gear paddleshift from 2003. Power ably transferred to the driven wheels via four-wheel drive and a limited-slip differential at both ends. The final outing for Lambo’s now traditional steel spaceframe construction. Steel brakes initially but a carbon ceramic option followed soon after launch. Design ushered in the current obsession with creases, and in some style – Luc Donckerwolke had designed the stunning A2 for Audi and moved to Lamborghini when the Germans stormed to power. He’d already produced the facelifted Diablo before delivering its successor in 2001.

Engine (SV): 6496cc 48v V12, 661bhp @ 8000rpm, 487lb ft @ 6500rpm

Performance: 3.0sec 0-62mph, 212mph

Weight: 1565kg

Length/width/height: 4705/2058/1135mm

CAR said then: ‘Right now, rough edges and all, the SV is as exciting a supercar as money can buy’

Verdict now: Sensational swansong for the original Lamborghini V12

Rating: *****

Aventador

Number built: 4000 so far (2011-)

Price then: £247,767

Value now: £250,000

Brand new V12 sticks with 6.5-litres but gets massively oversquare internal dimensions for unheard of response. New ISR paddle-shift ’box is quick but brutal and there’s no manual option. Aventador brings Lamborghini’s chassis tech bang up to date – core is a carbon monocell, bookended by aluminium subraframes that can be easily replaced in a smash. Suspension gets fancy pushrod dampers, but only the SV’s are adaptive. Donckerwolke had departed to Seat, leaving new design head Felippo Perini to create the body, which was hinted at by the earlier Murcielago-based Reventon. Roadster version had lift out panels, not Murcie’s farcical canvas cap.

Engine (SV): 6498cc 48v V12, 740bhp @ 8400rpm, 509lb ft @ 5500rpm

Performance: 2.8sec 0-62mph, 217mph

Weight: 1525kg

Length/width/heigh: 4835/2030/1136mm

CAR said then: ‘The Aventador doesn’t just move the game on from the Murcielago, it transports it to a new time zone’

Verdict now: All of the classic Lambo fear factor, but with none of the foibles. Almost a bargain

Rating: *****

Godfathers – the men that made the V12 dynasty

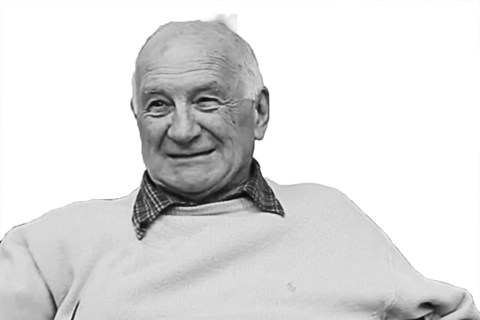

Ferruccio Lamborghini

Tractors, air conditoners, golf buggies, helicopters, wine, supercars: Ferruccio’s various businesses dabbled with them all during his 76 years. Supposedly started building cars to show Ferrari how it was done, but sold up in the mid 1970s.

Gian Paolo Dallara

The brains behind the Miura, young Dallara created the bare chassis shown at the ’65 Turin show and devised the transverse engine-above-gearbox layout. Founded Dallara Automobili, which supplies chassis to the single-seater world.

Paolo Stanzini

Dallara’s second in command, the talented Stanzini was also in his 20s when work started on the Miura. Took over chief engineer duties when Dallara left, and later developed the four-wheel-drive quad turbo EB110 for Romano Artioli’s short-lived Bugatti revival.

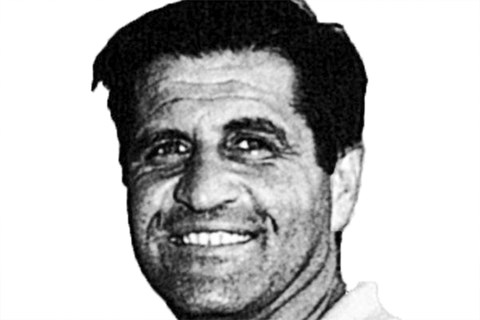

Giotto Bizzarrini

One-time Ferrari man had created the 250 GTO for Enzo but left in protest at Enzo’s re-organisation of the engineering department. His legendary Lamborghini V12 packed twin-cam heads compared with Ferrari’s singles.

The missing V12s

350 GTV

Lamborghini’s first car, and the first to get the Bizzarrini V12, was a stunning front-engined GT by Scaglione. Sadly it was significantly uglified for production as the 350GT, its engine detuned from almost 300bhp to 270bhp for manners

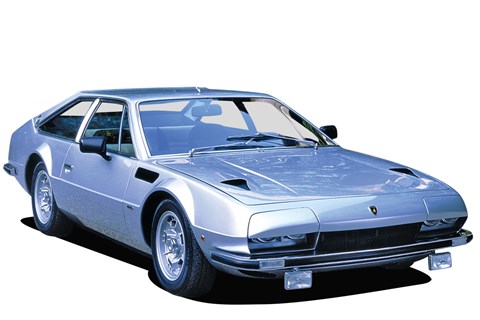

Espada

Inspired by the ’66 Marzal show car, the 1968 Espada had space for four but retained all the performance Lambo buyers had begun to expect. Estoque four-door concept from 2008 hinted at a modern version, but it never made production

Jarama

The subtle yin to the Miura’s showy yang, but again with the classic V12 under the bonnet. Built on a shortened Espada chassis, its life was equally truncated, lasting two years from 1970

LM002

Sant’Agata’s evilest was a V12 SUV with its roots in a project to supply off-roaders to the military. Urus spiritual successor on sale in 2018…