► Epic 10-day, 4155-mile drive across Australia

► Sydney to Perth across unforgiving desert

► Gavin Green retraces his father’s 1965 expedition

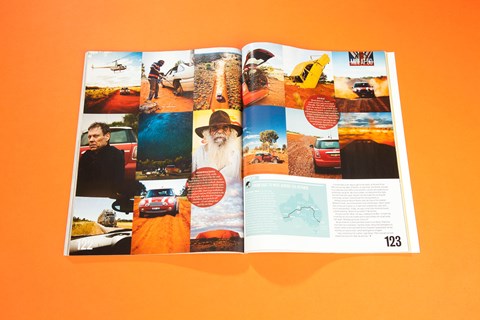

The Mini ploughs along the rough rust-red track, its belly grading the central ridge of the ill-defined road. The ridge is covered in hardy spinifex grass, which grows prolifically in the Australian outback, and the Mini’s metal sumpguard – protecting mechanical vitals – cuts the tussocks like a lawnmower.

Progress is slow. The Mini is just 90 miles from Uluru (what Westerners call Ayers Rock), heading west into one of the most deserted parts of the world’s most deserted continent. Speed rarely rises above 10mph. Majestic gums, tough little acacia and giant termite mounds bear witness to the little car’s travails. So do the occasional ‘big red’ Kangaroos and camels, looking on nonchalantly. Thick sand slows progress almost to a halt as the Mini’s front wheels desperately claw at the ground, seeking firm purchase.

Bang! Slump. On a sandhill the front suspension breaks. The driver feels the car drop as the left corner ploughs into the track, and the car comes to a stop, almost tripping as the nose digs into the loose sand. The Mini lies lopsided, like an athlete felled by a stitch.

The nearest settlement ahead, the old gold mining town of Laverton, is almost 800 miles away, and every one of those miles is on tracks that are either rocky, sandy, or just plain rough.

Yet the car is still mobile. So rather than turning back 400 miles to the nearest town (Alice Springs) for help, the crew moves on. They camp and, next morning, use their axe to chop wood. They carefully shape branches from a mallee tree. The timber is placed between the suspension arms and the body of the car. Magically, the car sits upright again. And thus, with no suspension on the front corner, but riding level, the Mini limps on to Kalgoorlie – where the suspension is repaired properly – and on to the west coast of Australia, through the Red Centre by land.

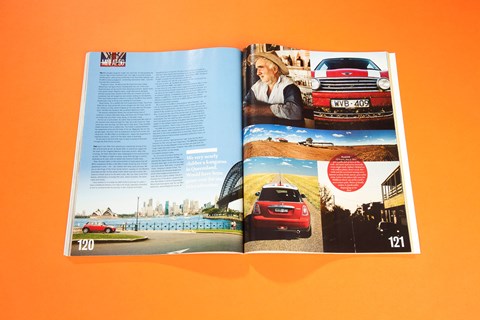

That was in late 1965. Four adventurers shared the driving of the Mini and its back-up car, an Austin 1800. A Land Rover supported the team on the roughest Western Australian stretch. After that crossing, the team then did a (less challenging) north-south journey as well. The figure of eight crossing, using Alice Springs in central Australia as its axis, took six weeks and covered 12,600 miles.

Now, 44 years later, on the same stretch of track where that old Mini’s suspension broke, a new Mini Cooper driven by one of those adventurer’s sons – me – also battles with thick sand and dust. We are on the fringe of the Great Sandy Desert, heading for the Western Australian border on this sandy tack (which now has a name: the Tjukururu road) and on to the west coast. We, too, have come from Sydney, attempting a crossing that uses, where possible, the same roads and tracks.

I have wanted to re-create my dad’s historic journey for years. I have a childhood memory of a map in his study, specially presented to him to commemorate his journey. It was of great Australian expeditions and among the roll call of worth Victorian explorers, with their thick bears and unsmiling faces and their formal woollen suits, stood a familiar name and date: ‘Evan Green, 1965’. His figure-of-eight crossing was the last entry on the map.

Plus, the time was ripe for a re-creation of that historic journey. This year is, after all, the Mini’s 50th birthday. And that’s why BMW, now owner of the Mini marque, was so keen to loan me a car and, what’s more, suggested a back-up vehicle too. We’d be going through some harsh and dangerous terrain, in a car about as well-suited to desert adventure as Gucci loafers are to outback trekking. A breakdown could be disastrous. The back-up vehicle is a BMW X3 – hardly a 4×4 tough guy, but they weren’t offering a Land Rover. Its driver is BMW engineer Darryl Cook, who happily proves great company.

My co-driver in the Mini is photographer Mark Bramley – like me, an Aussie in London. Mark’s a good mate. He knows the outback, he’s a good driver, and he’s the sort of guy who you can spend all day cooped up in a small car with and not want to kill. He’s also, as you can see, one of the world’s best car photographers.

Our brand-new Mini Cooper is standard apart from a big steel sump guard. The rear seat has been removed, to make it easier to carry two spare tyres and two five-gallon fuel containers (the fuel supply on the outback roads is at best inconsistent and in many places non-existent). There is also a five-gallon barrel of water.

The BMW 4×4 carries two more spare tyres, more fuel cans and other spares, while the satellite phone ensures we can ring for help even in the most isolated parts of Australia. There is also an emergency beacon that promises assistance within four hours, no matter where we are.

Tyres are a worry. I want all-terrain ‘rally’ tyres but the Mini’s unusual run-flat rims just won’t take them. The BMW/Mini engineers insist that the strong sidewalls of the run-flats will cope with rough roads and sharp rocks. However, they offer no reassurance about ride comfort on the deeply corrugated outback tracks.

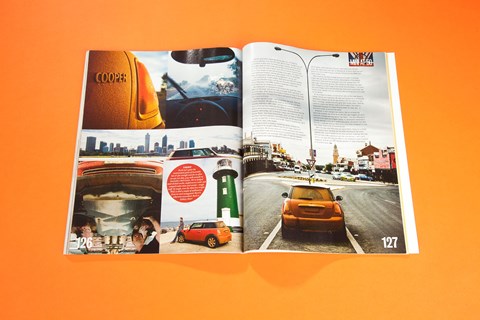

So, on a cool morning in Sydney, we set off across the harbour Bridge, passing the Opera House, just visible in the grey dawn light. In the first two days we cover about 1000 miles, on good flat roads, sleeping in decent hotels. The only hazards are the grey Kangaroos, which reach plague proportions at dusk. We very nearly clobber one as it bounces of the gloom, phantom-like near Barcaldine in central Queensland. Would have been game over for our Mini adventure, and probably for us to.

It should take us ten days to get to the coast, at the end of our 4155-mile journey. West of Winton, on day three, the tarmac narrows to a single lane and traffic is non-existent. Locusts are caught by our windscreen and grille. We cross creeks, normally bone dry, many now half-filled with water. Recent rain has made the countryside surprisingly verdant. Colourful parrots zig-zag above us. Halfway along the Winton-Boulia road, we stop at the isolated Middleton Hotel, one of the world’s most remote pubs. Owner Lester Cain comes out to greet us, in well-worn outback hat, open shirt, shorts and barefoot. ‘O’clay’, he says in that time-honoured Aussie outback greeting. ‘Where’re ya headin’?’ We tell him. His eyes narrow. ‘What’, he says, nodding to the Mini. ‘In that?’ He scratches his chin and stubble and his face breaks into a half-smile, half-laugh. ‘Whaddya gonna do. Carry it?’ We go inside for a drink and meet Lester’s son Stony. ‘That’s his real name not a nickname,’ clarifies Lester. Stony flies helicopters to muster cattle on the vast beef farms of western Queensland. He has recently survived a crash, which destroyed his chopper. `1 was unconscious for a while,’ says Stony. ‘Then I just got out and walked five hours for help. No worries.’

He might have been describing a minor traffic bump.

We meet an Italian opal prospector drinking at the bar; otherwise the old pub is empty. He tells us a king brown snake had recently bitten him. Stony rang for the Flying Doctor, which landed on the road and flew him to Mackay on the Queensland coast, 500 miles away. ‘He almost died,’ says Stony. ‘Browns are nasty bastards.’

A particularly nasty one lives under the pub. The outback is full of venomous snakes— browns, tigers and, worst of all, the desert taipan, which has the most toxic poison of any land creature. My 11-year-old nephew told me this, the day before we left Sydney.

We move on to Boulia, an oasis town on the Burke River — where the explorers Burke and Wills camped on the tragic return leg of their south-north crossing of Australia in 1860-61 — and overnight at the Australia Hotel, the same pub where my dad stayed 44 years earlier. Today the proprietor is Trevor Jones, the town’s former mayor. He’s a big, tough, no-nonsense man, in a small, tough, no-nonsense town. We have big steaks for dinner, and a big bacon-and-eggs platter next morning. This isn’t the sort of pub where you’d order a soya latte for breakfast.

We tell Trevor where we’re heading. A little red Mini with white stripes and a Union Jack on the roof driven by two boys from London is never going to impress. In Boulia, the usual set of wheels is a vast 4×4 Toyota with a ‘roo bar as big as the Buckingham Palace gates, tractor-like tyres and enough ground clearance to vault a small hatch. ‘Well, ya’ll neva get down the Donohue in this,’ he says. That’s the sand and gravel road ahead that is supposed to take us to the Northern Territory. ‘They’ve had heavy rain. Road’s been cut up bad. It’s for 4x4s only.’

Just a few hours later the Donohue looms ahead, and Trevor is right. A sign says the road is closed to all but high-clearance 4x4s. Our Mini, obviously, is front-wheel drive. And it’ll barely vault a pebble. Our first big test and we capitulate, looping north on tarmac roads, through the mining town of Mount Ise then Tennant Creek, before our halfway destination of Alice Springs. It adds 300 miles to our journey.

So, with 2400 miles on the clock (and nearly 2000 miles still to go, mostly on rough roads), we arrive at Australia’s best-known little country town. We drive down the Stuart and Lasseter Highways to Ayers Rock, and watch this eerie and deeply religious symbol of geological might magically turn from dull terracotta to bright orange with the sun’s last caress of the day. Then, as if in a bid to outdo itself, Australia throws the spectacular Kata Tjuta (The Olgas) in our way, the majestic rock formations that look like 36 orange-red domes standing proud of the desert. And then the tarmac stops. The real test is about to begin.

The road is sometimes rocky, sometimes sandy, never smooth, but the Mini scoots along well enough. We are very near where my dad broke down 44 years ago. We pass wild camels, grazing on hardy spinifex grass, grown luxuriant in the recent rain. The terrain is rough and deeply weathered, beaten by millennia of scorching sun and harsh winds. Rich red sand hills form between clumps of hardy acacia and eucalyptus. There are grey, gravelly rises. We are entering Australia’s Great Sandy Desert, one of the driest areas of the world’s driest continent. The sun, hot and strong, stands smug over one of its greatest conquests. Forty years ago no outsiders ventured here. Nowadays one vehicle uses this road every few hours by daylight, and almost every one of them is a 4×4.

A motorcyclist approaches, wearing Darth Vader helmet and integral dust mask, a long rooster tail of dust chasing his chunky back tyre. He waves at us to stop and pulls up alongside. He speaks with a French accent and is riding a big Paris-Dakar style dirt bike. ‘Turn around!’ he exclaims. ‘The sand ahead is terrible! You’ll never make it! Especially,’ he adds rather dismissively, looking at our car, `especially in this.’ We ignore him. There is, after all, no alternative, short of diverting to the north or south coasts, adding over 1000 miles. Amazingly, more than 40 years after my dad’s journey, there is still no sealed road from east to west coasts through the centre.

And the sand does indeed get worse. Big ruts, cut deep by previous vehicles, scar the soft road. We hit it fast, trying to use our momentum to skim over the loose surface. Initially, we slow as the nose digs deep into the rough and the Mini almost grinds to a halt, as it first hits that wall of sand. I turn off the traction control to get those front wheels to spin and we break loose again, the engine revs with newfound freedom, and we gain speed. From the passenger seat, photographer Mark yells encouragement: `Go, go, go?’

The combination of light weight, wide tyres and high entry speed means the little Mini keeps surfing over the sand. Engineer Darryl Cook, following in the BMW, reckons it looks like a little radio-controlled toy car skipping over a beach.

We sweep past an abandoned 4×4 stuck in the sand then, soon after, on the other side of the road, a stricken 150ft road train, sunk up to its-axles. After about 20 minutes of intense driving on the wide but winding track, the sand thins and a solid gravel surface gives the car’s tyres solid grip.

Another big test is over — and we passed, this time. Then the routine resumes. We pile on the miles (or kilometres, out here)- steadily, listening to ABC radio — it’s the only station available for; most of our journey. Eventually the signal disappears, but not before we’ve become experts on local news, farming issues and the weather. Worryingly, rain is forecast. Heavy rain would cut worse, flood — the Great Central Road, which will take us from the Northern Territory/Western Australian border all the way to the tarmac at Laverton, in south-central WA. There is no diversion. We’d be stuck for days, even weeks.

Mark goes back to reading, sometimes aloud, reviews in a 4×4 magazine he bought in Mount Isa. It’s our major source of entertainment. We discuss what sort of 4×4 we’d buy if we lived in the bush (either high-tech Discovery or a Land Cruiser, the outback’s ship of the desert, we conclude, after days of vigorous debate). Just before we reach the Western Australian border, the rain starts failing. Little channels of brown water gush over the dirt track. We make camp that night at Warakurna. A storm destroys our temporary roof, made of a groundsheet tethered to the BMW and some mallee trees.

Next morning, the sky is a deep blue and the light is achingly bright. We see herds of feral camels, descendants of the beasts imported to help build the telegraph lines and railways over 100 years ago. Every time we stop, flies attack us. We camp that night near Tjukayirla, on the fringe of the Great Victoria Desert. The stars are surprisingly vivid in the ink-black sky. Even more surprising, two hungry emus wander into our campsite next morning and try to-steal our breakfast. As we prepare to leave, a truck driver tells us the road ahead is muddy. Storms are expected. We skip over bumps like a windsurfer skimming a choppy sea as the sky darkens and rain pelts our car. River crossings, usually bone dry, gush with muddy water. Nearing Laverton, where the tarmac road to Perth begins, the track is impassible because of a deep flowing creek. So near, yet… a diversion routes us around the water.

Whatever. It can’t dampen our elation. We’ve survived the worst the outback can throw at us. We don’t get bogged; we don’t puncture. A brake warning sensor has failed – the dust affected it – and there are dash and tailgate rattlings. A subsequent examination reveals damage to the car’s underbody piping, the plastic fuel tank shroud is smashed, and 5mm thick solid steel sump guard now 3mm thick. That’s a lot of bottoming out.

After ten days and 4155 miles we reach Perth, ready for a break and a decent bed. The little car has been impressive, far more capable over such ill-suited terrain than we ever imagined. But next time we have a Mini adventure we’ll do it on tarmac — we’ll use a 4×4 for our next off-road trip. Mark is still reading his well-thumbed magazine. And we still can’t decide whether to take a Discovery or a Land Cruiser.