► Roof down to the roof of the world

► Cheating death on the world’s highest road

► Ben Oliver takes a Mini to 18,000 feet

The road out – our only road out – was quickly being eaten by the raging, flood-swollen river 50 feet below. The hillside into which it was built had partly collapsed, eroded by the torrent beneath, so the outer half of the road was just a crust of blacktop with nothing to support it. The inner lane looked stable enough, for now, but the river’s appetite wasn’t waning and unless we got the cars past before the road fell in completely they’d be stuck between the resulting chasm and the dead-end in the other direction until a new road was built, and our plan to drive this Mini Cooper from Delhi to the top of the world would be dead on day three.

So what else could we do but take a deep and possibly final breath, floor the throttle and hope the river didn’t choose that moment to swallow the rest of the road? The oddest thing about the experience is that looking back over our ten-day, 2000-mile journey, it doesn’t really stand out as a danger highlight. Driving a road car to Khardung La, the Himalayan mountain pass that claims to be the highest motorable road in the world at 5602m, or 18,380 feet, or 200m higher than Everest base camp, or half the cruising altitude of a passenger jet, was never going to be easy, but we didn’t foresee all the varied and inventive ways in which this trip would try to kill us.

We knew about India’s horrific road-death record. We knew about the dangers of driving at extreme altitudes: confusion and vomiting are merely incompatible with dignity, but pulmonary and cerebral oedema are incompatible with life. We took medication to help us adapt; any drive that requires drugs must be interesting, right? And then there are the militant Kashmiri separatists. The Foreign Office advises against ‘all but essential travel’ immediately to the north of Khardung La, along the ceasefire line between India and Pakistan, and driving a Mini convertible to the world’s highest road doesn’t count as essential travel. Like the drug requirement, you know your drive is going to be interesting when your map has ceasefire lines and disputed territories marked on it. India, Pakistan and China face each other up in the Himalayas; if World War Three starts, it may start here. Bill Clinton called this ‘the most dangerous place on earth’.

So we really didn’t need the freak rains that killed 34 people across northern India in our first couple of days there, and ate our road and caused the landslides that would later nearly end our trip. And particularly not when we were doing this in a Mini. Why a Mini? India has just become this riotously successful British brand’s 100th market, and this magazine started out as Small Car and Mini Owner in 1962, so it seemed right in this anniversary issue to link the two with one of the adventure stories this magazine later invented; one which will literally never be topped. We’re pretty certain that no convertible has ever been driven over Khardung La, and we liked the idea of going roof-down to the roof of the world.

A word about that ‘highest motorable road’ claim: the Indian authorities still make it, but it is actually a couple of hundred metres short of their claimed 5602m. There are two unmade passes in Tibet which are higher, one of which is reported to be crossed by a weekly bus service, which probably qualifies it as ‘motorable’. But the buses there are short, high ground-clearance designs that will go over boulders that would defeat Land Cruisers.4 There’s no evidence that a road car would make it over these passes. And they’re in Tibet, so good luck persuading the humourless Chinese authorities to let you go find out. Khardung La remains the highest road you can actually drive over.

But first you have to get there. Snapper Charlie Magee and I landed in Delhi in 48degC heat and heavy humidity and met Bunny Punia, an Indian journalist and old friend who has been over Khardung La on two wheels and four, but never in something with as little ground clearance as our Mini. It’s a 121bhp Cooper with the six-speed auto ’box standard in India. I have an insurance policy: a rented Toyota Fortuner, a locally made proper off-roader, an SUV based on a HiLux pick-up which we’ve filled with jerry cans, spare tyres, radios, a steel towing cable and essential mountain supplies such as water and bags of cheese puffs. All of these will be needed.

A long way in India feels a lot longer than anywhere else: from Delhi we have a two-day drive just to get into the foothills of the Himalayas. A couple of hours in and Charlie says he’s already using his testicles as worry beads, and we’ve seen most of the sights that make Indian roads such an intense, exhausting, terrifying experience. We dodge the gutsy remains of a stray dog, and only spot a beggar sleeping in the street when he shifts onto his side because his near-naked body has taken on the exact shade of the dust in which he lies. There are cows in the road, and stick-thin rickshaw riders who arch and strain against the pedals, using all their meagre body weight to get their overladen chariots moving. There are families of four on one scooter, the children looking vulnerable and delicate amidst the furious swarming traffic, their arms as far around dad’s belly as they will reach, eyes tight shut against the dust and fumes, or the rain. There is a sadness in the dissipated ambition of the big projects started but seemingly abandoned – bridges and bypasses and shopping complexes and cinemas – and in the environmental havoc; the great piles of rubbish, the dense black clouds of soot from the ancient, gaudily decorated cargo trucks. It can be hard to see the mysticism in modern India.

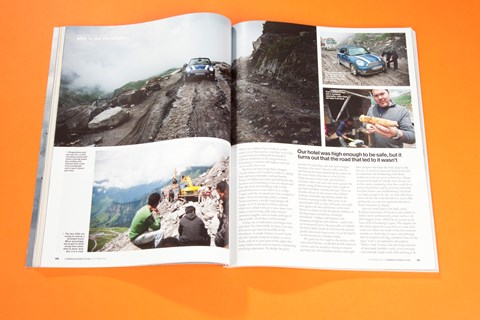

We spent our first night in the relative calm and cool of Shimla, an old British hill station at 2200m, and our second at Solang at 2600m; gaining only a few hundred metres each night slows progress but helps the body adapt to the thin air. As we drove up to our hotel in the dark we could hear the thundering of the flood-swollen river but not see it; in the lower villages we passed through the people were already out on the streets, wondering what they could do to protect themselves, and by morning some had lost their homes and smallholdings. Our hotel was high enough to be safe, we were told, but it turns out that the road that led to it wasn’t. But getting the cars out just required some nerve. Worse obstacles lay ahead.

Just two roads lead to the high, exotic Kashmiri provinces of Zanskar and Ladakh in India’s most northeasterly corner, and to Leh, their biggest town, which lies at 3500m at the base of the Khardung La pass. The supplies for the entire region for a year have to come in by truck over these two roads in the four summer months in which they’re open, and although they’re marked with big, confident lines on the map, ‘road’ is an optimistic description. There’s some Tarmac, but also long stretches of deep mud, boulder crawls, river crossings and unmade single-track with nothing tocatch you if the edge gives way as you squeeze past another oncoming, non-slowing truck.

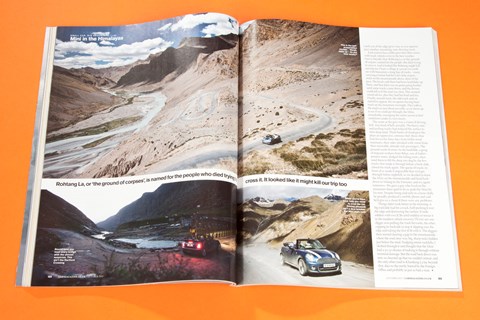

Each road in has a killer pass that often seizes with stuck vehicles even in the best weather. Ours is literally that: Rohtang La, or the ‘ground of corpses’, named for the people who died trying to cross it. And it looked like Rohtang might kill our trip too. From a village at 3200m we could see with binoculars a long line of trucks – many carrying aviation fuel for Leh’s little airport – stuck on the mountainside above, short of the pass. The locals said there had been landslides up there, and that there was no point going further until some trucks came down, and the drivers could tell us if the road was clear. This seemed sound advice, plus they had hot food and tea. Finally, around noon, the odd truck and car started to appear, the occupants having been stuck on the mountain overnight. They told us the road was just about passable, so we drove up to see if we could get through; the Mini, remarkably, managing the entire ascent in foul conditions under its own steam.

The scene at the pass was a vision of driving hell. Any kind of hell, actually. The heavy rain and jostling trucks had reduced the surface to shin-deep mud. Thick banks of cloud gave the place an oppressive, ominous feel. Buses that had driven for three days from Delhi stood stationary, their sides streaked with vomit from their miserable, altitude-sick passengers. The ground stank of urine. In the landslide, a gang of migrant workers from Bihar, one of India’s poorest states, dodged the falling rocks, then used them to fill the deep ruts dug by the few trucks that made it through before a fresh slide closed the track again. The queue of trucks in front of us made it impossible that we’d get through before nightfall, so we decided to leave the Mini on the mountainside and head back down to Solang in the Fortuner, and try again tomorrow. We gave a guy who lived on the mountain three quid to let us park the Mini by his tent. Despite being clad only in a loose cloth, he proudly produced a mobile phone and said he’d give us a shout if there were any problems.

Things didn’t look better in the morning. A big rockslide had hit a truck, half-pushing it over the edge and destroying the surface. It took soldiers with two JCBs until midday to rescue it in the maddest vehicle recovery I’ll ever see: one digger arm pulling the truck forwards, the other cupping its backside to stop it slipping over the edge and taking the first JCB with it. The diggers then started clearing a gap in the mountainside where the road once was; big, sharp rocks hidden just below the mud. Dodging minor rockfalls, I sloshed through it and thought that the Mini had a 50-50 chance of making it through without terminal damage. But the road back down was now so churned up that we couldn’t retreat, and the only other road to Khardung La lay beyond that, days to the north, barred by the Foreign Office and probably in just as bad a state. In how many ways could this go wrong? If the Mini got stuck I didn’t fancy getting out to attach a tow rope in a landslide, so we hooked it to the Toyota before we entered the worst section. So now not only might we both get stuck, or pull each other over the edge, or be taken out by falling rocks (I put the roof up, like that would do me any good), but if the cable snapped it might take the spectators – who were ignoring the falling rocks to watch the trucks – off at the shins, for which jail time seemed likely.

But like the washed-away road, there wasn’t much choice but to get on with it. It lasted maybe 30 seconds, the Fortuner jerking the Mini forward as it bellied-out on the rocks beneath, the noises coming from the underside sounding like a pod of dolphins being massacred by Japanese fishermen. My elation on the other side is hard to describe: not only was the trip still on, after 36 hours in which I was fairly sure I’d have to call it off, but the Mini seemed fine, with no visible damage and the system check saying: ‘OK – no faults.’

Charlie had brought the theme tune from The Italian Job and saved it until now; I wonder if it’s ever been played in Kashmir before, but it seemed entirely appropriate. But beyond the Rohtang Pass everything changes; Led Zeppelin is the only soundtrack, and I saved one song in particular for the moment we crossed the border into Kashmir itself. We stopped in a little hotel with hard beds but a satellite dish through which we watched, bizarrely and with a bunch of stoned Tibetans, Andy Murray and Laura Robson lose their Olympic mixed-doubles final, before setting out the next morning to cover the 220 miles to Leh through most the heart-stopping, other-worldly scenery you’ll ever see.

Because these high, remote, serene, protected provinces are so bloody hard to reach they feel quite apart from the crowded chaos of the rest of India. The roads are almost deserted; the people visibly ethnically Tibetan. They smile beatifically and wave at our odd, out-of-place car as we pass. It wasn’t the height superlatives that made me want to drive to Khardung La. It was the landscapes of Zanskar and Ladakh, an environment almost impossible to access, its vast valleys barred in the very far distance by rows of snowy saw tooth peaks, the wide turquoise rivers with soft sand banks whipped into weird fantasy castellations by the winds, and the roads cut into the sheer sides of flat grey or metallic red mountains, looping further and higher than any others, anywhere, each bend revealing another prog-rock album-cover view that leaves you torn between stopping for a picture, or driving on to the next, higher, better view, or just weeping at the bizarre, barren, alien beauty of it all.

We were getting properly high now, the altimeter approaching 5000 metres, me reciting lists of Prime Ministers and Presidents backwards to check I wasn’t getting confused and was still fit to drive, the sun getting whiter and fiercer as we got closer to it, scorching my nose and cheeks, and the occasional ricochet as another bag of cheese puffs detonated in the boot as the air pressure dropped. Over 200 miles is a long way when you’re scanning every inch of road for potholes, and your speed suddenly drops to a crawl when the Tarmac ends and the ‘road’ heads off into unmarked desert. The hell of Rohtang had thrown our schedule, and the fuel station we’d planned to fill at was closed, forcing us to buy some from roadside traders in a little truck stop called Pang (not twinned with St. Tropez). One trader, blind drunk, emerged with two jerry cans and a fag and started trying to fill the Fortuner with diesel while smoking. He insisted the other can held petrol but a sniff told us it wasn’t, and we bought some from someone sober instead. Refuelled, it took us until midnight to cover those 200 miles, which meant driving over the Taglang La pass – at a claimed 5328m second only in height to Khardung La – in the dark. When, exactly, did I start thinking it was okay to scale the world’s second-highest pass over unmade, unmarked tracks in now near-freezing temperatures and pitch-black night, in a Mini with the roof down? At least I couldn’t see the drops.

But the Mini didn’t seem bothered at all. My observations on the car might not seem relevant if you won’t drive yours at 18,000 feet, but I was genuinely impressed by the toughness of this little car. Once the mud of Rohtang had dried and fallen from the underside we could see that the exhaust was as dimpled as a golf ball and the oil pans for the engine and gearbox had been seriously reprofiled, but being pressed steel, had bent rather than cracked. A radiator hose had been pulled away from its mountings but was easily fixed. The cabin and hood mechanism were deluged with talcum-fine desert sand but both continued to work faultlessly and the Continental run-flats didn’t puncture despite hundreds of miles over vicious little stones. The engine started to lose torque only over 4000m; on start-up, it would idle roughly until the fuel system noticed the lack of oxygen, then smooth itself out. And most importantly the brakes were just always there, whether stamping on them to avoid another oncoming truck, or constantly brushing them to bring the car down two vertical kilometres in an hour. If you’re going to sell a car successfully in a hundred markets, it needs to be properly engineered for all circumstances, and this one plainly is. And you’re particularly grateful for those qualities when you’re three miles up and hundreds from a mobile-phone signal or hospitals or any other kind of help.

Leh, population 28,000, felt like Manhattan after that utter, eerie isolation. And I felt like the coolest man in town in my Mini convertible: everyone, from Buddhist monks to Western travellers staring at it like it’s a supercar, and locals who’ve never seen a soft-top before demanding to see the roof in action. The final, 30-mile drive from Leh up two vertical kilometres to Khardung La looked relatively tame compared with what we’d been through, but we still decided to have the car blessed by a young monk at the ancient Tsemo monastery on the way up, the prayer flags he fixed to the Mini’s windscreen possibly saving us in the closest we came to a head-on about five minutes later. The climb took two hours, the Tarmac ending with about ten miles to go and leaving us with a couple of deeply unpleasant rock-crawls to negotiate, the Mini cambered down towards oblivion, but just trickling calmly and sure-footedly over them as we’d come to expect it to.

And then we rounded a bend and were there: Khardung La, 5367m by my altimeter, and regardless of the disputed claims, as high as you can drive a car. I’d been reading about this place for ten years, been planning this trip for months, and been convinced at least twice in the last few days that I wouldn’t make it. So when I finally did, I leapt out of the Mini, but nearly fell back in with the sudden, weird, dizzy head-rush from the lack of oxygen. So you walk in pigeon steps across the 50-metre pass, eyeballing proper Himalayan peaks in the far distance but at the same altitude as you, and obeying the notices in English and – bizzarely – Spanish not to sacrifice any animals. There’s a hut with oxygen, which we didn’t need, the world’s highest cafeteria, serving cups of tea, which we did, loud Buddhist prayer chants played on loop by the little monastery almost hidden by the tangle of prayer flags, and entirely appropriately for the end of a journey in this most English of German-owned cars, a detachment of Indian soldiers playing cricket three and a third miles up in the sky. I joined in, and edged my third ball to short leg. At that point, it started to snow, and it suddenly felt like the right time to leave. Ever felt like you’ve pushed your luck as far as it will go?