► An archive gem from CAR’s back catalogue

► ‘911’s popularity costs Porsche hard cash every day’

► Plus Ian Fraser tests latest 911 SC

As a last-minute reprieve saves Porsche’s 911 from death, Georg Kacher explains why Porsche would like to kill it but can’t and Ian Fraser takes the latest SC – bouncing back better than ever – out for a hard day’s drive.

This article was first published in CAR magazine in December 1980.

911: the road goes on

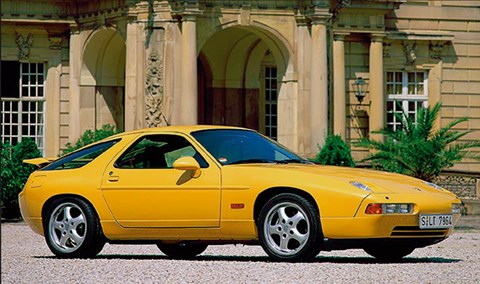

If the 928 had sold as well as Porsche hoped, the 911 would have died two months ago. But the rear-engined Porsche continues — and is likely to do so for some time — because it is still seen by many buyers as the only proper Porsche. They don’t care that the 911 — designed in the ’60s — is an anachronism compared with its new front-engined sisters; that its abilities are clearly limited compared with those of the ’70s-designed 928.

So the 911 — in SC, Targa and Turbo form — continues to have the steadiest sales of Porsche’s three models. It is the only Porsche to have amortised its development costs. Yet its continuing popularity costs Porsche hard cash every day because it forces them to produce three models in parallel rather than just two. Conversely, the 911 is a valuable prop to the Porsche 924, continuing — as it has done for the past 15 years — to be Porsche’s one real bread-and-butter model. Its unfaltering sales have kept up a steady flow of cash at a time when Porsche made their half-voluntary, half-forced switch to the new front-engined models, had to spend a great deal of money doing so and then earned less than they had anticipated from the newcomers.

Buying the 924 project back from VW — who had commissioned it as an Audi sports car then rejected it as too avant-garde and too expensive to build — cost Porsche £10m. There were further hefty developmental costs on top of that, and the 924 still costs Porsche money. Its break-even point won’t be reached until well into 1981. Even though Porsche recently announced that, in response to rising demand, 924 production is being increased from 74 to 86 cars a day, it is still more than 20% below the original target of 120 cars a day.

Nor, despite the help of the desirable 924 Turbo, is production likely to be further increased significantly. The unexpected sale by Volkswagen of the 924 engine production line to America has forced Porsche to develop new engines ahead of schedule (on the test benches are 2.2- and 2.5-litre fours delivering about 145 and 170bhp). Furthermore, 924 sales keep slipping on the vital US market at which Porsche aim 50% of their production. Last year’s 8349 US sales were down from 13,658 in 1978.

Porsche, who made 37,000 cars in both 1978 and 1979 and turned over about £340 million, are too small and too vulnerable to weather a major crisis. In the 1979/1980 business year they sold 10% fewer cars than the year before, but 1980/1981 looks even gloomier with the hitherto remarkably steady home sales having dropped by 18% from January to September this year. As a result, Porsche employees had to work shorter hours in September and October.

From the financial point of view, Porsche presently face two major tasks: on the one hand they will have to spend about £80m by 1984 to complete modernisation of their Zuffenhausen plant; on the other, they need cash for future development programmes and new models. Here is the likely —though unconfirmed — rundown of Porsche’s forthcoming projects:

- New four-cylinder engines for the 924

- A turbocharged 360bhp version of the V8 for the 928S

- An economy 928 with part-load cylinder-switch off system, à la Cadillac

- A 928 Targa, to be introduced after the 911 finally does die

- Launch of a new down-market spyder/coupe based on the floorplan and mechanicals of the 1981 Volkswagen Scirocco

If approved, the economy sports car will combine stunning looks and Porsche-like performance with a relatively modest price. The arrival of the 928 Targa covers much of the traditional 911 market and the rest will be taken over by the 2.5-litre 924 Turbo/Carerra.

Unfortunately, it will take years to realise what, for a company Porsche’s size, is such an ambitious and precarious project. Even though Porsche have for the ’81 model year cut the daily production rate of the 911SC from 45 to 40 (including up to six Turbos), the model still heavily outsells its declared successor, the 928, by almost 50%. Despite the addition of the superb 928S, Porsche cannot anticipate increasing the 928 production rate beyond 22 cars a day. Balanced against that, Porsche chairman Dr Ernst Fuhrmann says the break-even point of the 911 is around 20 cars a day —too low a threshold to stop the rear-engined models reaching their 20th birthday.

Porsche’s second problem child is thus the 928. It came too early and was not as refined or reliable as it should have been for the price, it looked different but not distinctly Porsche, it weighed 3200lb and it used too much petrol considering the fact that few examples delivered the promised 240bhp. Most early 928s developed between 220 and 230bhp, a suspicion indirectly confirmed with the introduction of the 1980 model which still delivers ‘only’ 240bhp despite a higher 10.0 to one compression ratio and the required switch to four-star fuel.

Slow sales forced Porsche to halve the 928’s originally planned production rate from 40 to 20 units per day. This correction upset earlier calculations and calls into question whether the development of an all-new engine for such a low-volume model will ever pay off, and whether the 928 will still be selling in 1987 when it will reach its break-even point. The car’s poor initial reputation did in addition quickly begin to leave its marks: the dealers resented the 928 because second-hand examples turned out to be virtually unsaleable, many Porsche customers hesitated because the 928 neither looked nor drove like a typical Porsche, and the marketing experts tore their hair out attempting to reprofile the damaged image. It is irony that even though both the 924 and the 928 have in the mean-time shaken off their teething troubles and are now truly desirable cars, the buyers still seem to waver and —especially in the case of the 928 — resort to the 911 instead.

Porsche’s motor racing activities have long contributed to the company’s sporty image, but even in this respect there is now sand in the gearbox. The list of more recent track problems includes the disputed and expensive withdrawal from Indianapolis, the loss of the 1980 European sports car championship to Lancia, the mistake of building only 400 Carrera 924s when you need 1000 to homologate the car in group three (some Carrera customers have reportedly already threatened to sue Porsche if they produce more than the originally announced 400 cars), and the refusal to rejoin Formula One racing notwithstanding the existence of what is said to be an almost unbeatable turbocharged 1.5-litre ‘baby’ engine that could make them champions.

Porsche still cannot make all the cash they need out of producing and selling sports cars. They also depend on the profits of their Weissach brain factory where automotive job orders are accepted from prominent car makers like Volvo, Lada, and of course VW. Porsche have had a close relationship with Volkswagen since Ferdinand Porsche designed the first Kraft-durch-Freude-Wagen in 1938. But so far the Porsche-Piech family has resisted the tempting grip of a helping hand — like in 1969 when ex-VW chairman Kurt Lotz’s proposal was met with a rebuff and Wolfsburg had to be satisfied with the foundation of the ‘VW-Porsche Sports Car Sales Organisation’ established to honour the birth of the traumatic Volks-Porsche.

In the eyes of Toni Schmucker Porsche must still look quite attractive: the models would nicely round off the top of the VW Audi programme, the gain in image and prestige would be accepted with thanks, and the Porsche know-how plus the already interwoven dealer network are additional assets. I don’t think that closer co-operation would be a disadvantage to Porsche either: Schmucker’s cheque could enable Zuffenhausen to invest in more advanced technology, the mutual exchange of standardised parts and production facilities (spyder!) would support Porsche’s rationalisation plans, and the Zuffenhausen-Weissach engineering crew could become a task force within the VW Audi combine.

But these are only visions of a possible tomorrow — at least as long as Porsche are led by Professor Fuhrmann. The new chairman, however, who is expected to be elected by the Porsche-Piech family later this year (Ferdinand Piech, currently chief engineer at Audi and the most obvious choice, was earlier rejected by the board) may soon hand over the helm —for a rumoured £2.5 million worth of Porsche shares.

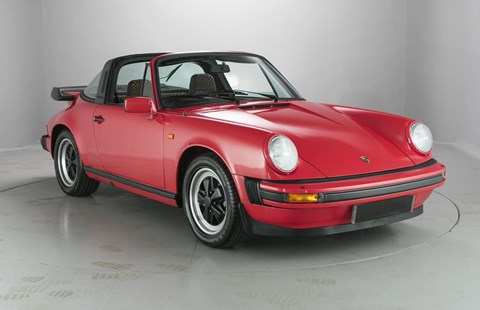

Driving the new 911 SC: past its sell-by date?

Ian Fraser tests the latest Porsche 911 SC

Like Rasputin, the Porsche 911SC is hard to kill and tricky to handle. It is a shadowy figure, a spectre of pensioner power lurking beside the mainstream but refusing to be carried along with it. Rather annoying when you consider the grand plan to phase out the anachronistic 911 in favour of those paragons of superbly executed conventional design, the 924 and 928. In the face of the newer Porsches, the 911 should be squashed as flat as last week’s road-accident rabbit, yet it haunts the logic that declares it has no place. Porsche would be glad to see the back of the 911 — if only their other cars were more widely accepted, specially on the German home market.

How dare a rear-engined, high-performance car survive into the 1980s when its demise was confidently predicted in the early ’70s! And who would have thought that the French, with their predilection for front-wheel-drive, would continue to embrace the equally eccentric Alpine A310, the pair of them representing the only rear-engined true performance cars that ever really mattered anyway. How history will treat all this is something I just do not know, but perhaps the books will record that Porsche’s decision to put the engines up front was taken too late, allowing the 911 to dig a little too deep into the souls of men.

Where the 911 goes after this is also a highly speculative matter. Maybe it won’t go anywhere. Or perhaps tamer turbocharging will seep down from the 930. And if it does, would it not be a surfeit of riches? This time round, for 1981, Porsche have done what they are very good at and developed the injection six another— significant — stage upwards. They have left the outside of the car alone (who would want to spend a kaiser’s ransome on interfering with one of the best known shapes in motordom?) and paddled around in the combustion chambers instead, to increase the horsepower and decrease the fuel consumption.

The SC now has 8.5% more engine output (which cuts about three seconds from the 0-100mph time) and uses 17percent less fuel, at least on the standard consumption cycles. Thus, if you were content to travel at a steady 56mph, the car would go 35.3miles on each gallon.

Academic, really, since the normal cut-and-thrust of life means that you use the Porsche energetically. The truth emerges as 20 to 22mpg over a mixed bag of town and fast country running, rising to 25 with long distance cruising. But if you have to worry about fuel costs in a car of this price, you simply cannot afford it in the first place. Where it counts is in the fuel-stop frequency which, at 320 to 375mile (safe) intervals, can be made to coincide with human requirements. Note, also, that the fuel consumption for a 204horsepower, 3.0litre engine in a 2550lb sports car is nothing if not reasonable and a reflection of Porsche’s abilities as development engineers.

It’s also worth throwing in a historical fact: the standard 911SC’s power is now the same as the famed 1976 Carrera, regarded then as a hotspur’s ideal. Now that power is in the cooking model, for better or worse. In common with others, including the latest V12 Jaguar engines, high compression ratios have made their comeback in the SC. It has been jumped up from 8.6 to one to a four-star 9.8 to one. The pistons have been redesigned to achieve it and the injection and ignition have also been altered. So has the gearbox. First is in the main gate and fifth outside it, like an Alfa’s pattern. Fifth is now as tall as the Post Office Tower and is pointless this side of the de-restriction sign.

The enigma does not stop at the 911’s mechanical layout. Here is a Morganesque sports car of superb build quality, rivalled by just a handful of makers and bettered by only one or two, with a seven-year anti-corrosion warranty which so contradicts the Italian approach. Porsches are built to look as though they will last for a decade or two and presumably will do just that. Yet all that deliberate refinement, that manufacturing care, that lovely engine, does nothing to counter the car’s thoroughly fierce road behaviour. Anyone who does not scare himself at least once in the new 911SC has simply bought the wrong car, or been fooled by the vehicle’s obvious qualities.

In a world weaned onto front-wheel-drive on one hand and passionate about mid-engines on the other, the outboard rear engine of the SC is increasingly at odds with its contempories. One has to search the memory banks to recollect how to treat such cars. Even if it does not come to you, the Porsche is equipped with reminders that you ignore through ignorance or complacency it matters not- at your peril. The SC is not a kid gloves car like some of the best mid-engined machines that require more sensitivity in the fingers than in the backside. The Porsche does not tap you politely on the shoulder or send chills up your spine: it simply assails your backside with the sort of information that was commonplace in the sports cars of the ’60s and early ’70s, and makes you saw at the helm to straighten it all out again. If you want to drive the Porsche fast then you must expect to be busy and, as they say, busy minds have fun.

In the dry, the back-end holds on well enough, however, unless you are prepared to tread in the power at the right moment, the front-end runs slightly wide and the only rectification is to turn up the wick. Wet roads are something to ponder. Understeer can be fairly pronounced and the power cure works just the same; but too much power snaps the tail around in a big rush that you need to be expecting but which can be fun if you are. Furthermore, the front wheels, still lightly laden despite the artificial weighting, tend to lock early on slippery or loose roads.

All of which is another way of saying that the SC places its driver in the position of having to concentrate unusually hard to ensure that little is left to chance. Once you come to grips with this idea the Porsche is immense fun to drive in a rancorous way, even more rewarding than some of the up-to-date exotica. In that may be the SC’s longevity. It is touchy to drive, but enjoyable because of it.

There is such a thing as being too good, too refined and too risky to exploit the high upper limits, almost beyond the skill of even very experienced high-performance drivers. They go from one place to another a great deal quicker than any 911SC but do such drivers have as much entertainment getting there? The SC is man-sized with no pretensions of being a state-of-the-art car. It’s a boney vehicle in which the basics show through; that’s made unavoidable by the age of the 911 and by the age from which it evolved.

But having said all that, I must also say that the SC is a safe car. Safe because whatever you do in it you do with your eyes wide open. You have done it because you chose to ask that of the car. For example, I always knew was going fast in the SC, not because it felt crude but because it felt fast: 130mph in the Porsche was as fast if not faster than any 130mph I have done in anything. Exactly the same at 50, 80, 100; the car reveals all so if you get it wrong there’s no blaming intangibles.

When you go around a corner fast you know it, for the steering (not power assisted, of course) has very strong reaction and if the surface is choppy it feels as though a Sumo wrestler is working out with the front wheels. Nor do road surfaces pass unnoticed. Although the suspension – torsion bars and struts back and front – has been mysteriously revised for the better in this latest SC, it’s no magic carpet.

Road noise has not been damped out – has it in any German car? – but running the car on 70series Dunlop Sport Supers strikes a happier medium than with the P7 set up on the last SC we drove (CAR July ’78). An SC that Georg Kacher drove in Germany had 215-60 Goodyear NCTs which he rated highly, although UK-spec cars will come on 70series rubber unless ordered otherwise.

There are a number of other inconsistencies that vary from wearisome through to entertaining, to worrying. The Porsche is terribly good on B-roads, the tighter the better. There’s a wonderful feeling of squatting low and thrusting mightily from one place to the next: the power, the suspension, the handling, the roadholding are all just fine. Yet the steering wears you out after a while and the brakes need quite a lot of leg, as does the clutch. On long, very fast corners, where not as much steering movement is needed, there’s strong reaction through the wheel and that desire to run outwards at the front, readily rectified with a blob of power. Typical British road humps fuss the suspension so that the car lands askew. Crosswinds are an element with which the 911 in at odds.

Part of the enigma of Porsche’s behaviour is its engine. Whereas the handling and roadholding can be criticised for lack of modernity and the inconsistency of behaviour that stems from its mechanical layout -the engine is hard to fault. Not only does it deliver power aplenty, it also spreads it like oil over water so that tractability has not been sacrificed to achieve upper-end whoomph.

So good is the engine’s pulling ability that I found myself doing second-gear starts in thick traffic to alleviate the need for one extra gearchange. You see, the clutch has a long, heavy throw with a sort of over-centre action that’s less than desirable. And the gearchange, with its floppy, long neutral -the only spring loading being between the fifth/reverse plane and the third/fourth positions – still leaves room for improvement.

I didn’t much like the weight or the speed of the shift, either. Initially at least, there’s a great temptation to over-use the gearbox because it’s hard to believe that the engine is capable of what it really will achieve for you. Fifth occasionally proves too high after you’re baulked in motorway traffic, but since the other end of its story is 146plus mph, lack of real accelerative ability at a mere 60mph is hardly surprising.

The 204bhp peak is at 5900rpm and peak torque – 197Ib/ft- is at 4300. Electronic breakerless ignition and K-Jetronic fuel injection give the SC immediate drive-away ability hot or cold and contribute to the overall completeness of the engine.

It will be for the engine, rather than the total ergonomics, that the 911SC is best remembered. Wheel-arch intrusion in the cause of obtaining a reasonable turning circle has caused the pedals to be offset towards the centre of the car, leaving the brake pedal in line with the steering column and the clutch close enough to the centre tunnel for it to be awkward to find a left-foot refuge.

A large lump of the speedometer face is hidden behind the steering wheel rim -the tachometer takes precedence in the display – and you have to be really thinking about it ever to glimpse the dial registering the contents of the oil sump. Various switches are scattered about, but the heating system is very efficient, being fast and well controlled.

All else is predictable. Good vision, marvellous seats, a handy compactness to the dimensions that makes the car so easy to place in traffic and on narrow roads. Finish and build quality are impeccable and there’s the imposing guarantee for the body as well as the mechanicals. Luggage space under the bonnet is better than it looks at first and can be supplemented by using the rear compartment after the trog seats have been folded down to make a carpeted platform. All the usual bits and pieces abound, such as cruise control, electric mirrors and windows, rear wiper, headlamp pressure washers. Servicing requirements are sensible.

At a very good £16,723 this is a complete car. But if I were parting with money for this 911SC I really would have to convince myself that I could live with the contradictions that it poses, that I would be content to accept the escalation of its outdatedness, that I would not be happier with a Ferrari, a Maserati, a Lamborghini, a Mercedes, a Jaguar, a 924 Turbo or, especially, a 928S. For my part I don’t think I could, anymore than I could in the past. It’s far too civilised to be just a ‘before Sunday breakfast’ car, yet too anachronistic to make you feel that you’re into the last fifth of the 20th century.