► We gain exclusive access to Rolls-Royce’s factory

► 800 hours to make a car ‘worthy of the badge’

► Plus the inside story on the ‘Black Badge’ models

There is an alligator on the table. An ostrich too. Both are very dead. They have been eviscerated and tanned (not in a good way) and are now laid out in the room at the Rolls-Royce factory where customers work with designers to create their guaranteed-unique car. The ostrich hide looks like a vast black deflated balloon but the alligator is immediately recognisable. Only the underside is soft enough to be used. Its legs and tail are largely intact, and its former sphincter looks up at me with a forlorn, one-eyed gaze.

You won’t find much ex-alligator at Nissan’s Sunderland plant, although it seems a bit pointless to point out that Rolls-Royce’s Goodwood factory is unlike any other in this industry when its cars start at a nearly a quarter of a million quid, and can easily run into seven figures once it has billed for the bespoke work which the overwhelming majority of its customers now ask for.

If you struggle with the notion of a new car costing that much, you need to come here and witness the skill of the staff who will line your boot with alligator if you wish and execute (almost) any other request you might make with infinite patience, and who won’t give you your car unless it is utterly perfect. One custom paint-job took 18 times longer than average. Calculated at an hourly rate, a new Rolls-Royce starts to look like better value than Tesco.

The trouble is, you can’t come here and witness it. Rolls-Royce is a surprisingly, refreshingly unstuffy organisation and a fine corporate citizen, but it does not offer factory tours to the public. It prefers to reserve that privilege for customers, and there are customers here every day who might prefer not to be seen by the public.

So unless you’re already a customer, you’re going to have to come in with CAR. My appointment has been made in a rare gap between actual paying clients. The time is inconvenient for me. I try to change it, but it is gently pointed out to me that it’s probably going to be harder to change the clients’ schedules than mine. I arrive at the appointed time.

You probably know that there’s a car factory at Goodwood, but even if you’ve been there for the Festival of Speed or the Revival you’re unlikely to have seen the factory unless you have business there. ‘Obviously, we couldn’t have allowed a smoking great factory at Goodwood,’ said Lord March. ‘This isn’t the 19th-century Ruhr.’ So it lies just south of the motor circuit, partially sunken in former gravel pits and barely visible from the surrounding roads. Once past the gates, the drive sweeps up over a crest and finally reveals Sir Nicholas Grimshaw’s 2003 design. It is striking and modern but more functional than flamboyant: less of a statement than the McLaren Technology Centre. It doesn’t disguise the fact that it’s a car factory: you can see straight into the assembly hall from the big, square central courtyard into which the chauffeur-driven Phantom sent to collect customers will sweep. I parked around the back.

There are two really important things you learn whenyou’re allowed inside this place. One is that idea of value. The bosses of car makers such as Rolls-Royce and Ferrari like to talk about themselves as purveyors of luxury goods: in Ferrari’s case, to benefit its stock market valuation. It’s true to an extent, but they still have a depth of engineering and craftsmanship which requires huge investment in staff and facilities, justifies their prices, and just isn’t present in handbags or pairs of shoes whose insane price tag is more to do with the label.

For that craft and engineering, you go through the front door and turn right towards the assembly halls, as we will shortly. But first, and for the other lesson, we turn left, like the customers. This is something they’ll be used to, assuming they ever fly scheduled. Here, past a vast 1930s Sedanca de Ville and one of just 28 original Silver Dawn convertibles built in the ’50s, is the suite of rooms reserved for their use. Rolls-Royce might make around 4000 cars each year now, but it doesn’t have 4000 customers because some of them order 40 cars at a time. Torsten Müller-Ötvös, the CEO, says he still knows a significant proportion of them personally. And a lot of them come here to the factory to design their cars and see them being made.

And that’s the other thing you learn about this place. A few of these people might easily have revenues that exceed a million dollars a day, but they’ll happily spend one of those days here choosing how to deploy that alligator around the cabin of a car which they might only use a handful of times before it gets lost in a collection of hundreds of others. The experience of creating their own car – the way they’d commission a work of art, or a new house or yacht – is as important as the end product. So it had better be a pretty bloody special experience.

Michael Brydon is one of the bespoke designers who provides it, his background in superyachts proving useful in coping with the demands of ultra-alpha customers. He shows me around the ‘atelier’, a room intended to inspire customers with examples of what’s possible. Hence the alligator, the ostrich and an odd assortment of other items, including a canoe paddle (I forgot to ask why).

With a ‘standard’ palette of 44,000 colours, and some customers creating and naming their own and reserving it for themselves for all time, it’s not like picking between three different silvers in a BMW dealership. You can have your royal crest embroidered or tattooed into the leather, or set into the veneer, which might use wood from your own forest. You can have the famous starlight headliner reveal your crest, or the night sky when your child was born. And if you want something functional to solve seriously first-world problems such as where to stow mucky polo boots, these guys can make it. ‘We want to get across the notion that there are no limits,’ says Brydon.

Really? How does Rolls-Royce cope with customers whose taste lags their budget? ‘We are not the arbiters of taste. If a customer wants to do something bold, we can work with that. We are here to give a level of steer, and usually customers will take our guidance. We certainly won’t do anything that compromises the car’s safety or legality, and there are certain things that we will not interfere with, such as the Spirit of Ecstasy, or the grille. It must always be a Rolls-Royce. But if a customer really insists on a colour… it’s actually amazing how good the pink cars look when they reach their final destination.’

It’s unfair to focus on the more garish bespoke cars, although Rolls-Royce doesn’t try to conceal them. There are books in the atelier showing previous bespoke cars with shocking spearmint-green cabins, and one double-pink example inspired by the colour of the lining of a pair of rubber gloves, also pictured, which the customer provided. But there are just as many very cool, very tasteful projects. One of Brydon’s favourites was a car inspired by the space-race of the 1960s, finished in white and pale grey with orange detailing and titanium cupholders.

Whatever is conceived here has to be made on the other side of the building. The assembly line, usually the heart of a car plant, seems like a side attraction here. Rolls-Royce likes to boast that there are only two robots in the factory, both in the paint shop, which we can’t see today as there is something ‘special’ in there. Given what we’re allowed to see but not mention, it must be pretty special: maybe a Cullinan SUV prototype. But the engines and the body-in-white both arrive here largely complete from Germany, so the heaviest, noisiest, most complex and most automated work is done elsewhere. This place is all about the stuff that can’t be done elsewhere: the paint, leather and wood, and bolting it all together without scratching anything.

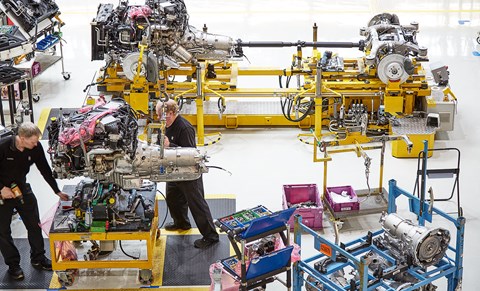

So the two assembly lines – one for Phantom, one for Ghost and its Wraith and Dawn derivatives – move incredibly slowly. In a normal car factory, the ‘takt time’, or the interval between the start of production of each new unit, and thus the time the car spends at each build station, is measured in seconds. On the Ghost line it’s an hour, and on Phantom, two. There is an oddly serene atmosphere. The cars are held in rotating cradles, not unlike a normal factory, and are conveyed between the stations on a line. But unlike a normal plant, nobody seems to rush, and the lack of machines means you can hold a conversation without raising your voice.

This often proves useful, says Stephen Horscroft, a senior production manager. ‘If you’re an apprentice here, you might find yourself fitting a piece of trim one minute, and then talking to a customer on a factory tour who’s a king or a president the next. We do have a word with them about how they handle that.’

But the work that really makes a Rolls-Royce a Rolls-Royce is done in the wood and leather workshops to the side of the production line. Some other makers of traditional luxury goods would have you believe that they must be made byfifth-generation craftsmen working in the same gloomy sheds in which their forebears suffered.

In 2003 the new Rolls-Royce plant gave the lie to all that, producing at its first attempt a car that blew all of its rivals away with a quality of craftsmanship and material that went way beyond the automotive. I’ve written about this before, but I drove the very first Phantom released by the new factory and I remember most its tactile qualities. You don’t think about ‘feel’ as much, but your hands are almost always in contact with the car, influencing you more subtly than its acceleration or noise, or lack thereof.

Then as now, Rolls-Royce did this with craftspeople who hadn’t always made cars. The woodworkers come from the local boatbuilding and furniture trades; the leatherworkers made Savile Row suits and ministerial red boxes, or have fashion degrees. And they all talk constantly about that quality of feel, and the irreplaceability of the human eye and hand.

But it starts with the materials. The veneers are stored in a vast, walk-in humidor kept at a constant 28 degrees centigrade and 80 degrees humidity so they stretch perfectly over their substrates. ‘It’s like Bikram woodwork,’ jokes one worker. The thin sheets of exotic woods sit in neat piles and have names I’ve never heard before but sound like like Gwyneth Paltrow’s children: Santos Palisander, or Waterfall Bubinga. The leather comes only from young bulls (no teats) kept at high altitude (no ticks) on farms with no barbed-wire fences (obvious) and in herds which are brought into barns at night, because it’s less stressful, and stress causes the cow’s veins to bulge, and that can be unsightly. Relaxed cows: that’s how you make a Rolls-Royce.

Even then, the hides are all minutely inspected by hand and eye and any flaws marked and discarded before the patterns are cut from perfect pieces: up to 14 complete hides go into each car. In the wood shop they build up the substrates over which the veneers are applied by hand from sheets of tulip wood, interspersed with aluminium to meet crash regulations. The final layer won’t be seen but still has to be hand-filled and sanded so the veneer sits perfectly over the top. They could just make these pieces out of something else, by machine, but then it might not feel right, and wouldn’t sound like wood if you rapped it with your knuckles.

‘We do spend a lot of our time working on things that you’ll never actually see,’ says Martin O’Callaghan, the woodshop production manager. ‘But we don’t mind. Most of the guys in here are pure woodies. They’ve been around wood their entire working lives. They go home at night and work on their own woodwork projects. You might not know if it isn’t perfect, but we would.’

There is a faint sadness about the amount of skill and love that goes into these cars. You worry that it might not be fully appreciated by some owners, or that it might never be seen at all. In the bespoke section of the woodshop, where they make the most complex one-off customer demands, theyshow me the ‘mournful Panda’. As the name suggests, it’s a slightly doleful-looking giant panda sitting among bamboo shoots, designed by a customer and set in marquetry into the veneer panel which faces the front seat passenger. The whole scene is made of tiny laser-etched pieces of veneer of different shades and grains, all chosen and precisely aligned to create the bear’s coat or the bamboo leaves. It looks perfect to me, and about a month of someone’s life. But it was decided that the mournful panda was not quite centred correctly. So they just did it all again.

Once the wood and leather sets have been finished and checked (and re-checked) they are fitted to the cars on the assembly with the most painstaking care. Scratching something is unthinkable: like the panda, it might take a month or more to make a bespoke part again, and if the car is a birthday gift for a king, it really can’t be late.

Once finished and on its wheels, the car is parked in Stephen Horscroft’s ‘test and final’ area, where it gets its very final inspection. Despite the risks, every car gets a ten-mile test drive on the roads around Goodwood, before being returned to ‘zero-miles’ condition and dispatched – often flown – to the customer. The factory makes an average of 18 cars per working day and there are about that number parked here.

It’s one of the very few places in the world where you’ll see lots of Rolls-Royces. ‘I mean, you shouldn’t, should you?’ says Horscroft. It’s quite a sight, enough to draw in even those who work here. Part of Stephen’s job seems to be keeping slack-jawed employees away. One wanders in clutching a dangerously sharp-edged package as we talk. Horscroft has no hesitation in stopping mid-sentence to intercept him.

Not all finished cars are flown immediately to their customers. Some customers fly to their cars, which are revealed to them in their own private Geneva moment on a stage back in the customer suite. The lights dim, the music rises and the curtains draw back. Only the car’s headlights are visible at first through the gloom, and only as the floodlights around it light up do you get to see if that pink you ordered looks the way you hoped it would.

The car I’m being shown isn’t mine. I haven’t invested months of time and hundreds of thousands of pounds in it. But the drama of the moment is dialled up the car in question being the new Wraith Black Badge: the 2016 Geneva show car, and quite a departure for the marque. I’m looking at the car, and they’re all looking at me to see how I react.

I love it. Like the factory, Black Badge is a sign of a brand at ease with itself and confident enough to rethink itself. It just needs more alligator.

Torsten Müller-Ötvös, Rolls-Royce’s CEO

Was there a risk in moving this famous name hundreds of miles to a new factory?

‘I’ve never met anybody who said, “this is not your authentic kind of place because you moved down here 15 years ago.” You don’t need an old-fashioned atmosphere to demonstrate what craftsmanship is, or to prove you are authentic. Just look at this place. It is true. We have hired people with skills you normally don’t find in the auto industry, and trained people here over many, many years. It takes 800 hours until a car is worthy of the badge, and we are crazy with the details.’

Why have bespoke builds become such a massive trend in the luxury car market?

‘In the whole luxury goods business, people want to make pieces as individual as possible. It’s like you’re creating your own piece of art. You are the painter. Our designers help you, of course, but it’s your creation. That’s what makes it so special. That’s why our customers spend the time. It’s not only about the experience, but also that they later can tell a story about what they have crafted here. They can tell their friends the story of why they chose this wood, or why they asked the guys to make that kind of marquetry.’

Should Rolls-Royce go a step further, and go back to one-off, coach-built bodies?

‘Coachbuilding would be my dream, real coachbuilding. We had it, but it disappeared. It became too expensive. Today there are homologation issues and that makes it costly. But ideally, I would love to bring that back, and we are investigating it. Of course we’ve had requests from customers for it. We can’t live up to their expectations yet, for technical and capacity reasons. So that’s something which comes at a later stage. First, I need to make sure that we are 100% bespoke in terms of what the majority of customers expect of us. This is almost done and dusted. Then we can go to the next step. That’s my clear vision. And of course, the new aluminium spaceframe architecture makes it easier to do stuff like that.’

Black Badge: Rolls’s M Sport?

Rolls-Royce is a brand in a constant state of reinvention, and that process will accelerate in the next couple of years. At the Geneva show it revealed the Ghost and Wraith ‘Black Badge’ models. This is as close as Rolls-Royce will get to a performance badge. The black Pantheon grille and Spirit of Ecstasy and the carbon wheels and cabin trim are very striking, but the real news here is that Rolls has dialled up performance and involvement with a new mechanical package.

Just don’t call the new cars ‘sporting’: they’d prefer ‘spirited’, and point out that owners probably already have a bunch of supercars in the garage. Both Black Badge cars get tauter body control, more weight and precision in the steering, uprated brakes and remapped transmissions which hold gears longer and downshift sooner.

The forthcoming Cullinan ‘high-riding vehicle’ will also get the Black Badge treatment, but the next Phantom is unlikely to. Phantom production finally ends this December after 14 years. Because this is Rolls-Royce, the replacement can’t arrive immediately, so there will be a year’s pause before Phantom VIII comes in early 2018. It will share the same new aluminium spaceframe architecture as all forthcoming models, and the hiatus will be used to switch the factory to the single production line all will share. Unsurprisingly, the current Phantom Coupe and Drophead Coupe will not be replaced, having been duplicated by Wraith and Dawn.

After spectacular and near-constant growth since its rebirth in 2003, Rolls-Royce sales slipped slightly to 3785 cars in 2015, solely due to plunging demand in China. Expect a reasonably calm couple of years before Cullinan arrives in 2018 to boost sales to 7000 or more. Having grown four-fold since 2009, Rolls could do with a rest.

Read more CAR magazine features