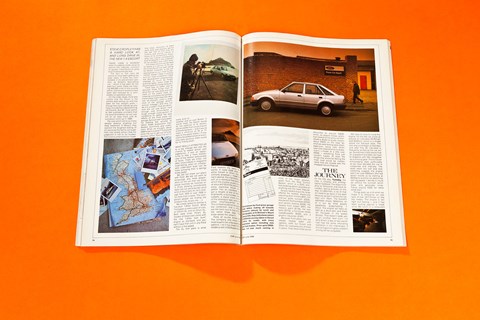

► Ford Escort sales neared 900,000 units in June 1986

► ‘Cars which sell to so many people deserve anything but easy treatment’

► Steve Cropley embarks on the most epic of road tests

There came a moment when it suddenly made sense to submit the ordinary, common or garden Ford Escort to some kind of extraordinary test.

The tact is, this car’s life seems to have been getting too easy lately. It looks too comfortable in its pre-eminent position as Britain’s best-selling car — which it has been for the past four years. Sales are nearing 900,000 units in this country alone, and recent revisions have been well received by a completely co-operative press.

On the wider stage, Ford also claims that the Escort is the world’s best-selling car and has been for five straight years — though this claim stands up only if you include the underwhelming US Escorts. But Mr Ford seems to feel justifiably confident that his second-smallest car will now roll on an easy track until its successor turns up in 1989. Yet, cars, which sell to so many people, deserve anything but easy treatment. In Britain, they warrant the toughest testing of all, because the family car buyer here has clearly shown that his judgment is not to be trusted. The Cortina phenomenon made that clear; 4.2million of them were sold over 20years, yet for the last half of that time the Cortina was plainly inferior to many of its competitors. Popularity can induce complacency and blind spots in the judgment of car builders and users alike.

For these reasons we decided to review our opinion of the job the Ford Escort has been doing for British motorists. Is the car appropriate to our most fundamental needs? Does it entirely suit our road conditions? Have the development programmes, stressed so much by Ford’s publicity types, really made the Escort superior in long, hard use?

There was no better way to discover these things than to drive the car very long and very hard on the public road, eschewing completely the genteel, home-every-night road test. Why not, we thought, cover a large slice of the average driver’s annual mileage? And why not do it in a week? That would ensure the car was driven hard enough and encountered a tough enough cross-section of conditions to defeat the best efforts of the Ford press car garage, famous over many years for treating test vehicles to rather better preparation than dealers commonly give customers. What, we thought, about 5000 miles in a week? That would every kind of weather and all over Britain. It would mean the Escort would try the patience of its drivers, stand a better than usual chance of breaking down — and it would need a minimum of 16 or 17 trips to the petrol station. If new claims for performance or economy were spurious, there would be no hiding place.

What really attracted us to a big mileage test was the chance to repeat actual user experience; it was an opportunity to take a more realistic view of the relative seriousness of faults. There are times, not often encountered in magazine road testing, when an untraceable under-dash buzz can be more annoying than a spongy brake pedal.

We did not share our plans with Ford. We did not want to encourage any more preparation on the car than we knew would routinely be lavished on it. (Ford, showing considerable style, has not yet acquired what kind of stunt took its car’s mileage from 1600 to over 7000 in no more than a week. The company’s people are finding the answers now, as you are…)

We simply asked to borrow a five-door 1.4-litre Escort. What Ford gave us were a pair of cars, an Escort GL and an Orion GL. Both were silver. Ford’s GL models of these cars come from the new 1.4litre ‘lean burn’ engine as standard and you can’t have that unit in any Ford without a five-speed.

The GL trim pack is what Ford reckons the family man wants. It costs £559 more, in either Escort or Orion model, than the similarly powered L model, the rep’s special. For that money, as well as a standard five-speeder, which the market usually values at around £120-£150 (and which every Japanese Escort competitor has as standard), you get a couple of bits of exterior bright work, a tachometer, better carpets, a digital clock instead of the analogue type, and a few other inconsequential items. This is hard evidence to support the contention that L models are the best cars to buy among the ranks these days. They show where the value is.

Ford, of course, knows this. The company also knows that most buyers like a few expensive options – so it has made the GL model a sort of £559 pass-key to most of the major goodies, apart from the Stop Control System, which is a £315 anti-lock braking option available on anything but the base Popular.

So you need to buy a GL to be offered the heated, electrically adjusting door mirrors (£97), the manual glass sunroof (£326), the electric front windows (£203), and central locking (£234), the heated front screen (£97), the metallic paint (£118), the rear belts (£113), a full-house stereo radio/cassette (£208) and a graphic equaliser (£167).

Because Ford press cars are always heavily laden with options, both our Escort and Orion GL had every one of these in place. That meant their prices amounted to around £9000 which, as anyone knows who’s ever looked at the price list then asked a dealer to quote, means about £9500 on the road. So what we are testing were small expensive, luxury cars which bear little resemblance to everyman’s L-model at a little over £6000 – something Ford just couldn’t supply. At least the things that would be feeling the most load would be components that are shared with the cheapest Escort Popular.

The journey

On the first day, Tuesday, the crew is Cropley and the photographer Goddard. The object is to drive to Penzance and back to London, taking pictures on the way. It’s 650miles; a lot of that will need to be done in the dark because we don’t collect the car keys until 10am. The Escort’s odometer shows 1654miles, all of it run by Ford people apparently pussy-footing it about. The engine still feels as tight as a drum-skin in the power delivery. That doesn’t body well at all; another ‘lean burn’ 1.4 we’d driven a day or two earlier had had the same infuriating hesitation in the mid-ranges. If this car’s gremlins grow, a week’s driving will be purgatory.

We have no time to nurse the engine. On the M4, we cruise at around an indicated 80-85mph and 3500rpm, which is a shade above the flat-spot area. The rain and wind begin at Swindon and after this, 80 indicated is frequently as fast as the car will go. Sometimes it falls below that on a gradient and often we have to dispense with fifth altogether as a cruising gear. This is not an encouraging start, particularly as we have decided the car is overpriced and ordinary. The seats seem too soft and lack cornering support, the engine won’t rev over 5000rpm (the red sector mocks us by starting at 6500rpm) and the car seems too well equipped. I decide it could do without the sunroof, which leaks and generates noise. Fancy paying £326 for extra wind roar!

Things perk up a bit when we make it to Penzance on one tank of fuel (317.2miles on the trip meter). The engine is still tight but freeing – and it has been pulling against a headwind. We lunch in a restaurant called. The Buttery at about 4pm, continue on to the Marazion coastline opposite St Michael’s Mount for a photography session, then cross to St Ives. The camera locations are fabulous in the low light of sunset, but we have to drive on. Only 333 miles have been covered and it’s getting dark.

The Escort shows off its excellent lights on the motorway trip back to west London. We stop near Exeter to eat and fuel up, but otherwise press on. Two night driving problems surface. One is a spot of amber light which reflects annoyingly on the right of a tall driver’s natural point of straight-ahead vision. The second is the way the fine elements of the heated screen catch and refract the glare of oncoming cars, especially when there’s road spray about. It isn’t a truly serious problem, but it’s annoying. Ford might be adventurous in specifying this option, but I decide I would do without it.

We’re through Exeter at 8.40 and in London by 1am. Goddard stops here, but I have to drive tomorrow. We’ve taken 649 miles off the total – well below the daily average of 715. That’s 66 miles extra I’ll have to make up.

We are late starting on Wednesday, the Escort and I. Not away until 7.57 and with 781 miles to do if I’m to get back on schedule. Though a long motorway is the best idea, I come off at the bottom of the M3 after heading south west out of London, take the slow A31 down past Wimbourne, then the A35 beyond Dorchester towards Honiton and Exeter.

This is bad travelling. The slowest arithmetician could eventually figure out today’s proposed 781 miles requires an average speed of 65mph, from a driver who sits solidly behind the wheel for 12 hours, taking no rest. So the foot goes down on the M5 and the car creeps along in the low 90s now, helped by the fact that its engine is definitely freeing and, for a change, the wind’s in the right quarter for a time.

But I am now more at peace with the car, apart from getting irritated with today’s two faults – an unstable lurch outward whenever the Escort passes through the bow-wave of a fast-moving truck, and a creaking, squawking noise from the polyurethane foam pieces that form the dash. Once you know what it is, the persistence of such a noise absolutely demolishes any illusions about the car having a ‘quality feel’.

Up the M5 we race, me noting the vastly different throttle openings the car needs to sustain an indicated 80, rather than 90. Also noting that the polyurethane squawk gets worse when the dash is heated by direct sunlight. I’m soon at work packing little bits of paper here and there to try to make it go away. No joy, though.

We pass three Ford Fiesta Populars, all still waxes and running on trade plates, travelling line astern at an even 83mph. I creep past and see that one, at least, has no reading at all registered by its speedo needle. I feel some sorrow for the owners who will take pains to run these cars in.

South of Birmingham, at Bromsgrove, I start to panic. There’s a road hold-up as three lanes – two full of trucks – channel into a single lane right where two motorways intersect. It’s 1.30, I’ve been going five-and-a-half miles, and the car has only 320 miles up. But in the afternoon, as they did yesterday, the miles climb more effortlessly. The car will sustain 85 in fifth now, though it still needs frequent down-changes to cope with winds or gradients. By dusk, around 7pm, I’m listening to the Radio Four news as we rush at full tilt past Loch Lomond on the A82. There has been a painless trip through Glasgow; Fort William seems a fair destination.

Just near Glen Coe I’m doing an even 80 through the night revelling in the even bends and the mostly good surface of the A82, when out steps a sheep confused by my headlights. It is necessary to hit the brakes very hard indeed. The tyres grip faultlessly on the damp surface, or at least I think they do. I’m not aware of a pulsating pedal but the car stops straight and the first bite and subsequent feel of the pedal belies the Escort’s lowish position in the motor car hierarchy. On the other hand, the dampers, which have caused me increasing impatience as I have begun to push the car on winding roads, do not control the body’s bounces well enough.

Anyway, it all happens in a matter of seconds. The sheep departs in fright and I proceed more slowly to Fort William’s West End Hotel, the first accommodation I see on entry to the town. The place has a welcoming entrance hall but the room is characterless and oppressive. I bet the proprietor has never spent much time in the room in which I spend the night. I park the car at 8.45pm, with 731 miles for the day.

It’s raining as I emerge, on Thursday at 6.20am, from the hotel where my sagging bed has kept me awake. My ill-humour isn’t helped by the fact that the insufficient rain gutter of the Escort dumps half-a-pint of rainwater in my lap as I get in. Still, the freshness of the early morning is invigorating, the car demonstrates its endearing characteristic of warming quickly (the manual choke can be pushed in after a few hundred yards) and I’ve nothing to do but drive on deserted roads to John O’Groats – and as far back towards the south as I can get. As the light spreads across the south-eastern sky behind – and we dodge the first delivery drivers in box vans travelling flat-out in the southerly direction – I realise what a supreme advantage in motoring it is to have a firm destination, and a schedule, and the license simply to do as many mile as possible.

This is where I really begin to enjoy the car – the steering’s perfect gearing and fair sensitivity, the comfort of its bump-absorption over untidy ripples (never mind the lurching over undulations) and the increasing smoothness of the engine, which now feels reasonable up to 5000rpm or so. I’m still hardly using fifth, and often not even fourth for long periods, however, owing to the winding, hilly conditions. But I stroke the car along, developing a kind of easy, durable, but fairly fast rhythm of driving. There isn’t a mood which gives greater pleasure.

But it’s windy. Later today the weather bureau will report a record gust of 153mph and somebody’s car will be lifted bodily by the gales in a western coastal village, and chucked in the harbour.

This morning it is quite demanding, keeping the car moving fast along the A82, beside Loch Ness, en route to Inverness. The road is wet, there are leaves and twigs coating the apexes of most corners. There is the potential here for a big, big slide, but the Michelin MXVs grip better than I can remember them doing on previous test cars. I clout somebody’s plastic garbage tin in a little town just past Invergarry because the wind has rolled it into the road. Sorry.

I realise, suddenly, that I’ve not wished at all on this journey for a bigger, faster, saloon car, or something with real potential such as a Ferrari or Porsche. -The fact is that these roads, though engineered to have beautifully regular curves, are a little rough for the likes of a Ferrari, a little confining for the likes of a big Merc.

I’m pleased, often, by the neat dimensions of the second smallest Ford. Some more power might be nice, but I realise, on past experience of the XR3i and RS Turbo, that the extra 30 to 50 horsepower would make itself available only if it brought torque steer with it. The 75bhp Escort 1.4GL has absolutely none of that, and I’m happy to settle for this package. Or, better perhaps, a 90bhp 1.6.

Yet this is not a slow car. In fact, if you drive it to the edge of untidiness, you’re going far faster than other road users want to go. It’s now possible to say the engine is approaching a ‘run-in’ state at 3000 miles-plus. It will improve over another 3000 yet, but the flat spot has disappeared.

I drive on up the A82 to Inverness (spending a fruitless 45min there looking about for Polaroid and film) on up the A9 through Bonar Bridge and Helmsdate to Wick, and finally John O’Groats. The absence of any control over the intermittent wipers’ ‘dwell’, annoys me in the drizzle. They’re too quick for the job and there’s nothing you can do about it.

Even more infuriating is the radio aerial, incorporated into the rear screen demister to thwart big city vandals. It does not work very well in either sense out here in remote Scotland. It fails to gather weak signals (you know that by the fact that its performance ebbs and flows according to your direction of travel and whether you’re on a hill or in a valley). And it does not work as vandal-proofing for the car, because there are none of those out here.

Somewhere along the road the thought strikes me that if, as people say, there are more Scots people outside the place than in it, they either must be the most adventurous souls on Earth, or the most oppressed by successive governments. Above the latitude of Glasgow and Edinburgh, the place is deserted, the people who do live there are truly nature’s gentlefolk and the scenery (and a lot of the road engineering) is memorable.

At the northern end of Britain, I pause to bash off a couple of crudely crafted Polaroids by the Orkney Ferry ticket office, then pause in the Stroma View souvenir shop. This is a mistake, as I do not enjoy a political harangue from an SDP-voting lady proprietor, who tells me in venomous tones that the awful Margaret Thatcher is only sustained in power by all those blacks in London voting for her. She wonders why we all don’t give David Steel a chance. I confess I’m not the man to ask, and escape gratefully.

Then it’s south towards Inverness, dicing with the first Volvo 360GLT I’ve ever seen being driven remotely well (we lose each other in a combination of curves, though), and out to Elgin in a dramatically slower manner, as vans, mimsers and caravans conspire to crowd the route of this Escort that just wants to gather mileage. Elgin to Aberdeen is freedom again — wide open roads; big sweeping bends. The winds that have delayed my progress on the northern run gather to press the car forward. On flat, straight sections the car runs at the ton. When the road changes direction and the gale is not pushing directly from behind, it’s almost as though the engine has suddenly gone off song.

I forge on through Aberdeen (where the traffic lights are hopelessly timed and the locals are rapidly getting used to traffic jams), then down to Dundee and Perth to join the motorways north of Edinburgh. The gale is still blowing, but the roads are uncluttered and the sky is clear. I race around the Scottish capital.

Heading down to the border, I take the A697 towards Coldstream instead of the better used, more direct, A68. There is method in the madness. Off the main route I take a six-mile detour to drive into Duns which was the home town of the late Jimmy Clark, the finest grand prix driver of the modern era and my hero of the ’60s. I have never been to Duns before. The place is deserted when I get there at 8.30pm. There is a plaque erected to his memory in the town, but I cannot find it and there’s nobody to ask. But it’s easy enough to recall my intense admiration for Clark and his exploits, and my disbelief that something he was so skilled at should kill him. And the thought strikes me that, although I never saw him race, had he survived, by now I might have met him. Even after all these years, that’s quite a thought.

Escort and I spear south, link up with the A1(M) above Newcastle. I’m supposed to be meeting John Lilley in the car park of Scratchwood services just above London at 9am tomorrow, but that’s still 300miles away and my eyes are displaying a marred determination to stay closed when I blink. So I give in at Scotch Corner and take a room in the motorway hotel there. I expect the worst but find it’s a comfortable, rambling place with a friendly face. The room is huge, the bed is large and soft, the bath is the biggest I’ve ever been in, and the price is reasonable. Much more than the motorway traveller expects. Escort and I have managed to put 754 miles into today.

The bed is so comfortable, it seems a shame to leave it early, but we’re on the road at 5.40am on Friday, heading for Scratchwood services, 240-odd miles away. It’s a straight thrash down the motorway, though I make a change from A1(M) to M1 at Doncaster. We accomplish the 243.5miles by 8.43 and Lilley’s early, too. He hands me the keys to a Renault 5 GT Turbo; we fuel the Escort and he heads off, back up the M1 to the M62, then west on the network of motorways that lead to the north welsh coast, destination Holyhead.

That journey west takes place largely in crosswinds, because today’s prevailing blows are big north lies. The crosswind stability, especially when there are gusts, borders on the unacceptable. Just holding the car straight requires real concentration, not because the steering is woolly, but because this car, eight percent more slippery than its predecessor, does not keep its directional stability.

Lilley and Escort press on to Holyhead after £1.98 lunch of steak and kidney pie, gravy chips at Penmaenmawr (it says in his notes), getting there by 3.30. Then it’s on to Fishguard (by 8pm) by which times its driver has decided he agrees with me that the car handles and stops uncommonly well. Only the lack of power – particularly passing power – irks him. The engine, now with better than 4500 miles under it, is sounding positively sweet (and continues to be free of flat spots or any kind of intrusive resonance). Now it is cruising quickly and comfortably on motorways in neutral conditions – if you can find any in this gusty spring week.

Lilley gets back to the office car park in Earls Court at 11.45pm, having accomplished 779 miles. With the extra 242 miles down from Scotch Corner, that is 1022 miles today. Which puts us on course to finish early.

I turn up at the car park a little after 7am on Saturday, read Lilley’s last illuminating note: ‘Final mileage 4811. Seat still comfortable.’ I make a note to ask him to show me some of his early poetry.

There are worse things in the world to do than to turn up at the office car park at 7.10am on a Saturday with the object of doing seven laps of the M25, London’s ring road. I know there are worse things. But I can’t think of any as I drive away. Saturday is spent dutifully lapping the M25, including the detour bit. It is accomplished in conditions of such mind-numbing boredom that I would rather not recall them here. Suffice it to say I spend £4.20 of the firm’s money on Dartford tunnel tolls (seven times 60p) three of the passes in a northerly direction, the others travelling south. I discover, furthermore, that the M25 is 121.3miles long, measured on a Ford Escort’s odometer, if you travel anti-clockwise. In the other direction it’s 0.65 miles longer. That’s measured predominantly in the middle lane, of course; the volume of slow Saturday traffic ensures it.

Still, this is the fastest day of all. A total journey of 868 miles in just under 14 hours, allowing two fill-ups and sandwich stops. That makes an average speed slightly ahead of 62mph. It will be a fairly long time before anyone bothers to beat that. It takes our mileage totally to 4032, with two days to go. The car has been fine, today. It has sat 85 to 90mph in conditions of light wind and variable congestion. The engine is terrific, now. It seems to have developed better throttle response with the miles. And if anything, it’s quieter too.

On Sunday, we take a tour through the Home Countries. London, M25, Oxford, Swindon, Bicester, Stow, Cirencester, Tetbury, then Reading, London and Dover. I can scarcely remember how I hooked them all up. Only that the journey put another 524 on the total, and that we finished up in Dover, where I stayed at the Moat House Hotel. It was OK, I think.

Back to London for Monday morning in the office that leaves 300-odd to be put away today. It comes easily enough from a motorway trip connecting Bristol, Birmingham and London. That, and a little sojourn around the M25 in the evening. Then it’s all over. There is no emotion except relief, but there is a realisation that few people who speak of it, have any idea of how far 5000 miles is. But I do.

The car

Our Escort 1.4GL covered 5034miles in seven days, without putting a wheel wrong. It needed its anti-lock brakes only once, to avoid a sheep in Scotland, but there’s some doubt that the car could have avoided the animal without them. It finished its journey extremely dirty, picking up loads of road grime from the dozen of detours one encounters in 5000 miles of open-road British driving. Apart from that, it finished without a bodily blemish, not even the mark of someone else’s parking.

To cover the distance, the car had to be filled 19 times, an average journey length of 265 miles. But it frequently showed that it could provide a 310-330 mile touring range, even when driven hard. And hard is the way it was driven. There is a considerable difference between the way you would drive your own car on the open road, and the extra effort you put into one like this, when the real object is just to gather in another mile. We drove at the very edge of untidiness, not so much guided for maximum speeds by the legal limit, as what we could get away with. That meant a voluntary maximum of 90mph indicated (84-85mph true) and about ‘eight tenths’. Full throttle was always used for passing manoeuvres. When the car wouldn’t pull the required 90mph in difficult motorway conditions, it was driven at whatever it would do.

Given this driving style, and the fact that our car’s engine was definitely tight for the first half of its journey, the fuel consumption was excellent. The overall consumption was 35.9 mpg, in conditions where we honestly expected no better than 30. The best figure of 44.7mpg was recorded on the high-speed dash down to Aberdeen, where the tail wind must at times have reached 60mph. The car seemed to be 20 or 30bhp stronger when it came up to pass a truck. The worst consumption was registered earlier that day – 27.1mpg – when the car was on twisty roads straining into the very wind that later assisted it down to Aberdeen.

As far as performance goes, the car’s smoothness and top speed improved dramatically over the week. From a point where its reliable maximum speed was barely 80mph, the car eventually freed up to a stage where it would show 110mph on the speedo. If given enough road. So Ford’s quoted 104mph is about right. The engine never revved comfortably beyond 5500-5700rpm. It would do it, but it lacked real bite up there and you were better advised to change up. The gearbox became slick and light towards the end, but that could not disguise the unhappiness (for fuel figuring reasons) of the ratios. The main problem was with the 22.5mph/1000rpm top gear, which was just too tall. The car would not cruise at 90mph and 4000rpm. It just did not have the torque. Had the gearing been lower, the car would have been much, much improved. We believe it would have given better ‘real world’ fuel figures simply because on this test we would have used fifth far, far more. As it was, fifth could not be trusted to maintain our momentum.

The 1.4-litre, five-speed package is just about the bottom line for open-roads use. You do not actively yearn for more power (especially since this engine does not generate any bothersome wheel fight/torque steer, commonly found in more powerful Fords. But the 1.6-litre, 90bhp engine with five-speed gearbox is indisputably a better thing for all-roads use in an Escort. But it’s thirstier (by at least 10 or 15percent in actual use) and it costs more in the first place. It is not, furthermore, either quite as smooth or free from vibration periods as the 1.4. In fact, this new engine rivals the really good small fours of firms such as Honda in all but its somewhat sluggardly throttle response. If you want action in this Ford, you floor the throttle. No half measure will work.

The Ford Escort’s suspension is under damped for our all roads use. On the other hand, it is compliant over ruts, and quieter than most, too. And though the body will lurch on undulations, the car has quite manageable body roll. A little more low frequency damping and this would be the best of the cars in the tough small car arena. And that’s quite a step from the bouncy, jarring little car Ford began turning out in ’82. The same compliments are owed the handling. The car is a classic understeerer, but the roll is contained, as mentioned, and the car refuses to scrub at all, even in the wet. The standard Michelin MXVs might have been engineered for this car.

But for all the Escort’s good chassis, it must be pointed out that most other competitive cars have very similar abilities. A couple of model changes could very soon put the Ford at the rear end of a trio. The fairest thing to say is that the Escort is at a good class standard, incapable – as LJKS points out in our accompanying story – of being seriously criticised.

The Ford Escort, however, comes nowhere near to being the perfect car. Its tachometer (if ours is typical) takes unscheduled leaps around the dial, and reads slightly slow. Its push-push switches occasionally stick on (if one in our Orion is typical). Its interior console, a luxurious option, flexes when a leg touches it, destroying any illusion of luxuriousness. Though much of the add-on equipment is of commendably high quality (because it is frequently shared with the Sierra and even Scorpio) certain things stand out as tacky: the sunroof is noisy and too expensive, the graphic equaliser is a pretentious toy in a car which is naturally as noisy as this (or any small car). The electric windows are not needed. The front screen-heating element promotes a ‘greasy’ effect to the night driver’s eye. There is one extremely annoying reflection into the driver’s eyes from the instruments at night.

The interior light is crummy. The seats are too soft for the heaviest drivers and lack side support for all. The instruments are set so far into their new binnacles that the bottom third of their graduations can’t be seen by shorter drivers. That’s a bad fault in everyman’s car.

The king of faults for us, however, was that infernal squeaking polyurethane foam, buried down there in the dashboard. It is clearly a minor fault, perhaps confined to this car out of thousands. But it was also one which we could not fix, and which our friendly dealer would doubtless be reluctant to search for. Those things make it a big issue, worse than a slipping clutch or an oil leak. Yet the Ford is a good car. Not entertaining or fun, but faithful. Whenever we climbed back into it to do another few hundred miles, it just felt like home.

On just one occasion in 5034miles, the Escort refused to start. But I solved the problem. I turned the key again.

Escort rearmed

Late developers, who only when more or less full grown begin to realise their potential, are a phenomenon well known to educators; and this tardy triumph of plenitude over lassitude teaches us that we should not be too hasty to condemn the inadequacies of the young.

It is the same with cars: how often have we seen some potential rocket suffer delayed ignition, and only soar when all the introductory fireworks are forgotten embers? It is even so with the Ford Escort: I still remember (and Ford itself has probably not forgotten) my bitter disappointment in that car when it was new – but now, when its days might have been thought numbered, at last it emerges as the very image of all that was implicit in its conception, as though Mks 1 and 2 had been but larva and chrysalis. As never before, the Escort has become an important car; it has also become a good one.

It always looked good. Tall and boxy like all the others of its class, it somehow disguised this evidence of the usual economic constraints, to appear the most handsome Ford ever, and one of the crispest of its category. Alas for the reality behind the appearances. It was an ill-behaved little brat, rowdy in ride and perfunctory in manners, and whatever was supposed to have been done from time to time to make it better merely made it different.

Yet the Mk3 Escort is now beyond serious criticism. Miracles, as some of us recognise, are with us every day; but this is no miracle. It is as though a disconcertingly large number of designers, producers, testers and comptrollers had, after long and disordered argument, finally reached a consensus and acted in concert.

Appraisal began in the Duriton sanctuary of Mr. Engineer Mellor, who displayed and discussed dismembered engines and dissected brake systems. Much of this was calculated to make first steps look like completed journeys: Ford’s long-term plans for truly lean-burn engines, concentrating on efficiency in the part-load condition which prevails almost all the time in almost all driving, will lead to engines astonishingly different from today’s, working on different principles and weaning some new techniques.

I would not advise you to wait; by the time they come into production, some of today’s toddlers will be proving themselves late developers. All I will say of the present engines is that although they are fairly clever, they are not brilliant: only one of them ever reaches the 18 to one air/fuel ratio of which Ford advertisements are so proud.

What really caught my fancy in the Dunton engineering centre was the anti-lock braking system which Ford, cautious as all manufacturers must now be of tempting the providence of Trades Descriptions Acts, has chosen to| call a Stop Control System (whence SCS). (Here is another challenge to the blinkered folly of all those who would have us ignore motorcycles: like so many other good things in the modern motor car, the sensors and modulators of the Lucas Girling SCS system were originally devised for two-wheelers.)

Ford had faced difficulties in applying the principles of anti-lock braking to the typical modern small front-wheel drive car: negative-offset steering geometry imposes, requirement for diagonal split braking circuits; which complicates the engineering of a reasonably cheap system – and in this part of the market, no system that is not cheap can be thought reasonable. However, the rear tyres of such cars never do much of any consequence apart from keeping the tail off the ground, so Ford decided to turn that impotence to advantage. If the engineers could find a cheap and simple (and therefore presumably mechanical) device which would work on two wheels, and which could be mounted conveniently, then the Escort could enjoy the security and controllability that had hitherto been the costly preserve of the upper classes. Girling, its apparatus not yet good enough for motorcycles, but good enough for cars, had something, which precisely fitted the Ford bill.

Trying it on the snows and ice of cryogenic Finland proved more than the efficacy of the SCS. It proved the value of the heated screen, the effectiveness of the wipers and cabin heating, the good balance of the estate version of the Escort, and the smoothness of the new 1.4-litre engine. Driving the Escort in England, where the roads are so much busier and the weather so much more changeable, proved how much better were all the minor controls which now raise the Escort to a level of ergonomics at which the Fiat Uno may be challenged.

It showed that on the chaotically inconsistent road surfaces of Britain, the ride of the Escort is now as good as it should be, the levels of mechanical and aerodynamic noise lower than they were, and the predictability of handling (together, or so it seemed, with the surety of roadholding) somewhat better. It also confirmed the incalculable value of the SCS, tried to finality in test-track conditions far too dangerous to simulate on the road. To kick the brakes hard at the apex of a 70mph corner, to kick them hard while swerving round an obstacle at 50mph on a slippery surface, to kick them hard at about 60mph when the offside tyres were on dry road and the nearside tyres on wet and icy, would take even more nerve on the crowded roads of England than it took to use them hard on the snows of Finland. To retain full steering control in the first two cases – not merely enough to effect a lane change but even to resume the original line – or to enjoy a rapid yaw-free hands-off stop in the third case, is to discover regions of control beyond the aspirations of professional competition drivers, and expectations of safety in circumstances outside the control of ordinary humdrum drivers such as myself and, if I may make so bold, you.

The new Escort is greater than the sum of its parts. There is more to it than anti-lock braking, much more to it than mere fuel economy or exhaust cleanliness, or the possibility of hearing good music decently reproduced. All these and more matter, but the SCS matters most, for with it the new Escort has done more than just to make a mark: it has overcome a barrier. Because of that, and because of the influence that the Ford will have on other designs, multitudes of very ordinary humdrum drivers should in future find life easier – and possible longer.