► The off-road king bows at 68 years old

► We drive the cars bookending Defender story

► Across Scotland in Series 1 and Defender

Land Rover’s definitive off-roader founded an automotive empire, saved the nation in war and recession, and lasted 68 years. We drive the first one… and the last.

I’ve had a few genuinely alarming moments in cars, but never before in something with 50 horsepower, made in 1951 and only capable of 50-something miles per hour. I am sitting in a Series I Land Rover: or rather I’m sitting on it, because with the canvas roof off and the windscreen folded forward, the tiny car’s bare-minimum bodywork barely reaches my hips. Its highest point is the thin Bakelite steering wheel I’m grasping, and the only roll-over protection I have is my flat cap.

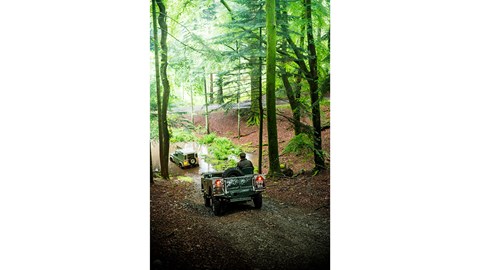

Ahead of me Land Rover’s Roger Crathorne, the Stirling Moss of off-road driving, is easing a modern Defender over the brow of a 50-metre, 40% descent whose gravel surface has been further loosened by the biblical downpour so typical of a Scottish summer.

There is a nasty step about halfway down that might easily break the car’s traction and there had been some debate about whether my 64-year-old museum-piece should attempt it. Roger volunteered to go first, and his Defender’s vertical rear end seems to tip almost table-top flat as it goes down.

As it skips over the step the engine braking proves too strong and Roger is forced – counter-intuitively – to get on the gas to raise his wheel-speed and sort out the coming slide. He brings the Defender down in one piece, and radios back to me that it is ‘probably’ okay to come down in the Series 1.

The Legendary Pioneer

I don’t have to make a case for the Land Rover’s inclusion on our list of British cars to drive before you die. It drives like nothing else on or off the road, and if you haven’t driven one yet, you don’t really know cars. We’re not specifying which Land Rover you should drive: instead, we’re driving two versions that bookend its 68-year history (and still share one common part) to see if we can detect any commonality.

But the green thread that links them connects more than just how they feel to drive. It runs right through the post-war history of this country, and is the real reason the Land Rover deserves its place on this list. It was first conceived as little more than a tractor, famously sketched out by Rover’s Wilks brothers in the sands of Anglesey’s Red Wharf Bay in 1947 and designed to make use of readily available war surplus ‘Birmabright’ aluminium alloy, and minimal use of scarce steel.

The result was so successful that it helped to kickstart Britain’s post-war car industry, bringing in desperately needed export earnings, opening new markets for all our car makers and sparking the British car industry’s huge export boom in the ’60s. The Land Rover moved explorers and aid agencies, and the British Army in every conflict since Korea.

Not all went overseas. The vehicle was as popular with British farmers as the Wilks had hoped: an MOT-failure Series II around a muddy field aged 14 is our most common first experience of driving. The armoured Land Rovers of the Royal Ulster Constabulary were on the TV news every night from the start of the Troubles in the late ’60s, and in the financial and industrial strife of the ’70s the Series III’s continued export sales kept bread on a lot of West Midlands tables.

Land Rover’s strength kept Jaguar alive in the last global financial crisis, and it now provides 80% of the sales of the modern JLR, a riotously profitable business that is once again creating new jobs by the thousand, building new factories here and abroad and pumping cars out through British ports, most significantly now to China.

The Wilks thought they might sell 50 Land Rovers each week: over two million have been made. The Defender, asit has been known since 1990, remains the brand’s heart but now provides only a tiny fraction of its sales, and this year it finally ceases production, killed by emissions legislation. Never again will this magazine, founded in 1962, bid farewell to a model that was around before we were.

This story is that farewell. Had it been less significant I might have bottled that descent. Instead, I put the Land Rover into what I hoped was first gear, let the clutch out slowly, planted my feet on its Bronze Green metal floor away from the pedals and let the car chunter over the brow on tickover.

As it tipped forward I did a press-up on that thin-rimmed wheel and gave a silent prayer that the retirement-age transmission wouldn’t slip out of gear, leaving me utterly buggered. It didn’t, of course. The revs rose, the tyres gripped and this pensioner just burbled down to the bottom with less fuss than the Defender.

‘God, I love the Series I’

And not just because it didn’t kill me. By the time I attempted that hill I’d already spent a day driving it over the Blair Atholl estate in the Highlands. I was meant to be driving Roger’s Heritage Edition Defender too, one of a limited run built to mark the end of production and already sold out. But I didn’t want to get out of the Series I and Roger, who retired from Land Rover in 2013 after half a century and has probably spent quite enough time in open Landies on wet, windy Scottish hillsides, looked quite happy in the Defender.

With its fabric roof in place the Series I looks top-heavy, under-tyred and ungainly, but with the roof off and the screen down that minimalist body suggests that it’s going to be fun. It is. Motoring journalists use ‘agricultural’ a bit too freely to describe a car lacking in refinement but the Series I really is only one step up from a tractor: the first prototype had the driver’s seat in the middle and this one still has a big hole in the back for a power take-off to drive farm machinery.

But it is astonishing how something so utilitarian can have so much charisma, and how much it can do with that 50bhp. At the pitiful road speeds it can manage you don’t really need the screen: you just pull your cap down tight and carry on your conversation.

But off-road it cedes less than you’d think to the modern Defender with its 120bhp and 265lb ft, partly because the burbly 50bhp petrol puts out a more diesel-like 80lb ft of torque. Once we turned off the tarmac and onto the gamekeeper’s tracks over Blair Atholl, I just pushed the yellow knob down for four-wheel drive, or pulled the red lever back for low-range, and let the little car get on with it.

‘Forget the modern obsession with autonomous driving’

Land Rover offered it in the 1940s. It copes with many obstacles at tickover: you definitely want to keep both feet away from the pedals when descending, and if it’s following ruts it even steers itself too. Because there’s no superstructure you seem to get tossed around less: you just sit upright on the seat-pad and let the car pivot under your backside. It’s almost comfortable, and the view out is as good as if you were walking or on horseback.

And that view is extraordinary. The bleak, grey granite contrasts with the pink-purple of the bell heather and the electric green of the new growth on the lodgepole pine. It wasn’t just John Brown that kept Queen Victoria coming back to Blair Atholl. Many of the rough bridges we’re crossing were built for her carriage, and it’s odd to think that the Series I was built closer to her reign than to these final days of the Defender.

The Series I makes our modern Heritage Edition feel like a Rolls-Royce for isolation and refinement. The steering is unrecognisable: now power-assisted and operated by a thick-rimmed wheel. And of course its off-road ability is greater, with its coil-sprung suspension, modern tyres, electronic traction control and a lot more grunt.

But you really do feel like you’re driving an evolution of the same car: it isn’t just wishful thinking. The sense of driving something that’s as wide as it is long and the view down to those sharp 90-degree corners is the same. The pedals have the same deliberate, heavy action. The gearbox has changed many times but it keeps the same slightly awkward feel of a short throw operated by a long, spindly lever. The fly-off handbrake is in the same place and works the same way.

And more fundamentally, the sense of modest but irresistible performance is identical. The autonomous-driving effect is even stronger in the Defender. Its remarkable, completely idiot-proof anti-stall system allows you to put it in first at the base of a steep, heavily rutted obstacle, take your feet off the pedals and your hands off the wheel and allow the car to drive up one side and down the other in complete control without any intervention. The fact that both cars can do so much themselves, mechanically and without sensors and a data connection, perfectly suited to and seeming to understand their environment, makes them feel as alive as any Ferrari.

Verdict

Landmark cars like these seldom disappoint. You don’t sell two million cars over 68 years on purely rational appeal, or if they’re no good to drive. You need to drive a Defender.

Six ages of Land Rover

Series I (1948-1958)

The very first Land Rovers had just 50bhp from a 1595cc engine, and an 80-inch wheelbase. Grew in length and power during a decade of production: over 200,000 were made. The earliest and best now sell for over £40,000.

Series II (1958-1971)

David Bache (of Range Rover and SD1 fame) ‘styled’ the Land Rover for the first time: the hallmark rounded shoulders survive on today’s Defender. Over half a million were made, production peaked at 56,000 in 1971.

Series III (1971-1985)

Syncromesh, a more conventional dash with the dials in front of the driver, and the County versions with tweed seats brought a little civility, but Aussies in particular bemoaned the plastic grille, which could not be removed and barbecued on.

90 and 130 (1983-1990)

One of the biggest changes, with coil-sprung suspension, a five-speed gearbox and the flush nose. This special edition was due to be one of 40 made to celebrate the 40th anniversary: strikes meant that only two were made.

Defender (1990-2007)

The arrival of the Land Rover Discovery meant the original Land Rover needed its own name. Series-production of the desirable V8 for the UK ended in ’94: this NAS (for North American Spec) soft-top V8 version with its roll-cage and bright colours sells for more than its list price when new.

Defender (2007-2015)

The arrival of the new four-cylinder Puma diesel engines was another step-change in performance and refinement, and is marked by the power bulge on the bonnet and blanked-off vents under the windscreen: no longer needed by a ventilation system that actually works.

Land Rover: born to explore

Barbara Toy

Land Rover’s most famous early ambassador was Australian Barbara Toy, who in 1950 drove from Gibraltar through North Africa to Iraq in her Series I, christened Pollyanna, before driving around the world in a Series II in ’58, and again aged 81 in 1990 in the restored Pollyanna.

Oxford and Cambridge Expedition, 1955

Six Oxbridge students drove two Series Is from London to Singapore in what is thought to be the first ‘overland’ expedition across the Eurasian land mass. They had to cross virgin jungle with no roads at all in their six-month, 18,000-mile trek.

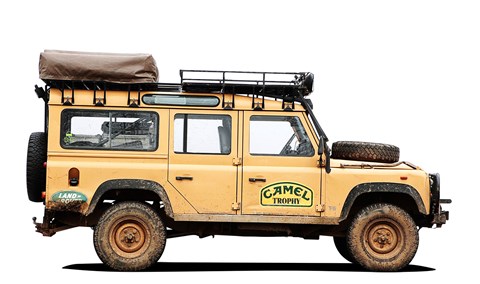

Camel Trophy and G4 Challenge, 1983-2003

Over 20 years, the Series III, 90, 110 and Defender ruled the Camel Trophy and G4 Challenge. Conditions were so tough in the jungles of Borneo in 1985 that teams covered just 2km per day. ’03 winner Rudi Thoelen swapped his Range Rover prize for two Defenders.