► New Le Mans centenary book reviewed

► Authoritative, insightful, surprising

► Coincides with landmark Le Mans race

If you’re telling the story of 100 years of Le Mans, where do you begin? Not in 1923; not really. Because this is not just the story of an endurance race usually held in June in north-western France. It’s the story of the modern world, of the sport-business-leisure nexus, of the automotive industry, of the advance of technology, of globalisation.

It’s also a story that explores the timeless urge to compete, to go further and faster for longer. And for all that, it’s about people focused on adding their name to the list of 140 winning drivers, and 25 winning manufacturers, it’s also a story about losing and failure and dying.

Le Mans 24 hours: a race fit for heroes

The race itself really began in 1906, the brainchild chiefly of Georges Durand – ‘a child of an age when France could glimpse the past and the future waving to each other. He was born in 1864, a year in which the country still had an emperor – Napoleion III, Bonaparte’s nephew – and Jules Verne published Journey to the Centre of the Earth.’

Although the First World War paused racing, it also in a sense hastened its progress. The pace of technological development picked up – the same would happen after the Second World War, too – but equally importantly it shaped a generation of future racing drivers. They’d tasted excitement, or tasted death, and were ripe for a peacetime challenge.

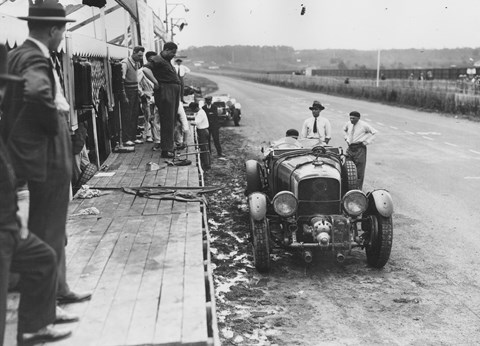

The burgeoning European and American auto industry had been quick to see the promotional benefits of doing well in an event that showcased a car’s performance and reliability. And in 1923 the race as we more or less know it began (although over the decades the format, the date, the time – everything has changed repeatedly).

All human life is here

The builders of the cars turned pro much quicker than the drivers. In the early days these were predominantly thrill-seeking toffs – the sort of people Williams had such a knack for describing in his Richard Seaman book, A Race with Love and Death. Here they’re often pithily sketched in wonderful footnotes. For example this:

‘In sixteenth place in 1934 was a Lagonda Special co-driven by Edward Southwell Russell, the 26th Baron de Clifford. Belgravia-born and Eton-educated, at 19 he had caused a stir in society by marrying the daughter of a notorious West End club-owner. An early supporter of Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists, he made speeches in the House of Lords advocating driving tests and speed limits. A year after appearing at Le Mans he was charged with manslaughter following a head-on collision in Surrey… The last peer to be tried by the Lords before a change to the law in 1948, he was acquitted. He was said to have earned his living in later years as a door-to-door dog-food salesman.’

Or this, from 52 years later, about Texan brothers Don and Bill Whittington, accused of financing their racing through illegal activites: ‘Bill, the younger, was jailed for 15 years after pleading guilty to tax evasion and smuggling marijuana into the US; he was killed in 2021 when his twin-engined plane crashed in the Arizona desert, the cause of the accident never determined. Don pleaded guilty to money laundering and was handed an 18-month sentence.’

Williams also goes out of his way to mention the many females who have competed over the years, their number much diminished recently, in a curious bucking of the general trend in sport.

The serious-but-fun spirit of the Bentley Boys continued for a long time, and to an extent survives today in the presence of ‘gentlemen’ drivers, although it’s been a long time since an amateur had any chance of winning the overall honours.

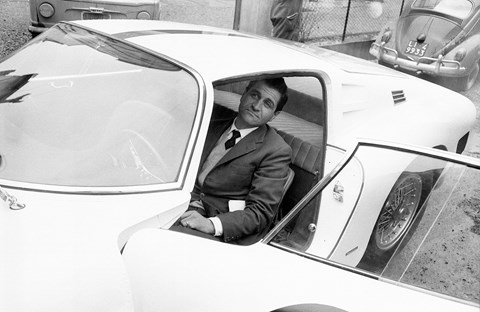

Meanwhile, the manufacturers were getting ever more solemn, and committing ever higher sums of money. It’s hard to imagine today that there would be a repeat of what happened in 1965, when Giotto Bizzarrini (above) – best known as father of the Ferrari 250 GTO that won Le Mans in 1962-64 – nabbed the class-winning Bizzarrini 5300 GT Corsa from the driver and drove it home to Italy after the race.

A special mention, though for ’90s team owner Charles Zwolsmann. ‘After his flower export business went bankrupt, Zwolsman did much better as a drug dealer, shipping large quantities of marijuana between North Africa and Europe. His success bought him a 115ft yacht berthed in Saint-Tropez, and in 1992 he launched himself as a team owner at Le Mans, with Heinz-Harald Frentzen, a future Grand Prix winner, and himself among the drivers.

‘He, Frentzen and Shunji Kasuya overcame various problems to get one of the cars home. Back in Holland the following week he was arrested for speeding, found to have violated bail conditions while awaiting earlier charges and sent to prison. There would be more arrests for drug smuggling and money laundering in the following years before, in 2010, he was caught in possession of 2000 kilos of hash and four guns. He died in prison the following year, aged 55.’

The highs, the lows, the unknowns

Periods like the Kristensen imperium and the Toyota default dominance inevitably have less drama than times when the winning drivers and winning teams have been harder to predict. So thank heavens for mavericks like Jim Glickenhaus, and innovators like Gordon Murray, and the rotary Mazdas, and Peugeot and Audi backing diesel (briefly), and the largely hopeless Nissan Delta.

In the new hybrid Hypercar era, all bets are off. Nobody knows if and when the Peugeot and Ferrari will get good, or how well the Cadillac will do, and what will happen when Lamborghini joins in next year. Like the Dakar, there are many reasons to think that Toyota (above) will win again, but it’s possible something entirely unexpected will rewrite the script and nudge the event onto a new trajectory. This survey of the first century is a fantastic primer for this year’s event, and beyond.

Williams guides us masterfully through the decades. He’s particularly strong on the 1950s and ’60s, with material that overlaps with his Seaman, Stirling Moss and Enzo Ferrari books (but never feeling secondhand). Yes, he’s better with people than with cars. And yes, one or two years get trotted through rather quickly. You might join me in wanting a bit less on the rule changes (so very, very many rule changes – about when you’re allowed to refuel, about how many hours one driver is allowed to clock up, about raising and lowering the roof…) but on the whole the mix of material is well judged, the storytelling well paced.

There are also times when you wish for a bit more of the author – more of the first-hand impressions that made The Last Road Race so special.

It’s an exceptionally good book – Williams, as ever, has researched it meticulously, marshalling his material into a manageable shape, and then telling his story with a propulsive energy appropriate for the event itself, and an eye for the telling detail that breathes new air into even the bits you think you’re familiar with.

24 Hours by Richard Williams, published by Simon & Schuster, £20