The man at the Swiss customs smiled indulgently when I told him that the Miura was simply a Mini Cooper turned back to front. Perhaps he did not altogether believe me; perhaps I was not altogether telling the truth. The Miura is really rather special. There are other cars whose rear wheels are driven by an engine mounted transversely in the tail, and some of them have nicely shaped and streamlined two-seater coupe bodies – but none of them can do anything like 180mph, and none of them costs anything like £8050.

If all this isn’t enough to make the Miura special, there is the tantalizing thought that there are only three or four in Britain. So when the time came last September for our East End friends Lamborghini Concessionaires to go and fetch another one it seemed that the occasion should be marked in some way. What better way – from my point of view, at least – than for me to go to Italy and help drive the thing back to England?

Providence, I must say, was looking after me very well inasmuchas (a) Mr Assistant Daniels was infernally busy because (b) Mr editor Blain was on holiday and (c) nobody else had been let into the secret. Little persuasion was needed to get me on a plane for Milan, little encouragement for me to hustle a Hertz-hired (and full marks to them for service) Fiat 125 down the autostrada to Bologna. The autostrada was not very busy and the folk using it were excellent mirror watchers, so the Fiat could maintain a noble 95 all the way while I sought to get my eye in for the fast motoring expected on the morrow.

Hunger is supposed to be the best sauce, and I must admit that I was mentally slavering in anticipation of the way the Miura would eat up the roads on my return journey. There is so much to look forward to with a Miura: that legendary V12 engine by Bizzarini, the reputedly brilliant chassis by Dallara, the spell-binding sculpture of the body by Bertone, and the final sorting and tweaking by Wallace. And think of it: £8050! The most expensive thing I had ever driven before cost a mere £8025 – but there, I suppose I just have to admit that my life hitherto had been humdrum and lacklustre…

There is another way of looking at the price tag: on a basis of pounds sterling per pound avoirdupois, the Miura is just about 50 percent more expensive than anything else I have driven before. Or again, £4025 per seat does seem rather a lot – especially when the seats are not very comfortable.

However, I do not think it was reflections such as these that caused such a crowd of excited Italians to cluster round the Miura as it stood outside our hotel (the sadly misnamed Jolly) in Bologna next morning. They weren’t crowding round it because it was so expensive or because it was particularly well made, for parked behind it was a more expensive and in many ways better made Series T Rolls-Royce with special coachwork which never attracted a second glance.

Maybe the Miura’s colour scheme had something to do with it: it was a particularly virulent lime green, with the details picked out in matt black – not a trace of brightwork anywhere on the car except for the little Bertone insignia on the flank. But surely this is the most exciting thing on the roads today, with that blind-looking and heavily slatted rear window so much part of the roof as to be almost horizontal, with those vast and obviously functional air intake scoops on the rear quarters, the vast windscreen and right up at the front those retracted Minnie Mouse headlamps pointing resolutely skywards. The whole thing looks magnificently absurd, expensive, expansive; it is 3ft 5in high, 5ft 9in wide, 14ft 2in long and it weighs the best part of a ton. It develops 350bhp, wears its own special kind of Pirelli radial ply tyres and has synchromesh even on reverse gear (yes – really).

Maybe it was a bit too much to expect luggage space as well. There is in fact a bit of a boot in the extreme tail, but the Lamborghini Concessionaires man did have rather a lot of stuff with him. My overnight case had to be kept in the car alongside my feet, my hat had to go on the floor beneath my knees. And I personally had to twist myself a bit in order to get in. Legroom on the passenger’s side was okay but headroom lacking, because the roof starts scraping downwards immediately aft of the windscreen, so only by moving my seat forward that my knees jackknifed into the air could I avoid a crick in the neck. This didn’t promise well for the next 1000 miles, but there was nothing that oculd be done about it now. The LC man made himself comfortable in the driving seat – he is about 5ft 10in and could enjoy a perfect driving position – and twisted the starter key.

The exultant whoop of a thoroughbred V12 is like nothing else in motoring. It is immediate, urgent, peremptory. The Lambo idles at about 800rpm and a gentle blip up to 2000 produced a sort of instant quickening of everybody in the square like a WO calling parade to attention. Mr LC slid the big lever into the gated slot for first gear, I breathed a private prayer that he might not be a nerve-wearing driver and we eased away into the busy morning traffic. The first gearchange showed me that I probably need not worry about my new friend’s driving: it was slow, methodical, straight out of the one-pause-two army drivers’ manual. Before the second gearchange I had time to appreciate that the low-speed ride over a rather broken, irregular road surface was surprisingly good – firm, but without shake or harshness. After the third gearchange, the last for some time, it dawned on me that the big four-litre Lambo engine was amazingly flexible. It might develop 87.5bhp per litre, but from ridiculously low revs it would pull as smoothly and inexorably as a Silver Ghost. Clearly this was going to be an astonishing motor car.

Looking about me I could see some astonishing things already. Glue, for example: yes, glue, between the carpeting and the sides of the back-bone tunnel that forms part of the chassis and fences off the driver’s compartment from the passenger’s. Clearly Mr Bertone’s bodybuilders are like all other Italian bodybuilders, though maybe not quite so bad (I gather that Englishmen buying Miuras usually take them to somebody like Hooper or Radford for an interior refit). Basically the interior décor is quite pleasing, the whole thing being done in dull black – leather, door handles, ashtrays, everything. Mark you, things like ashtrays are basically the regulation issue chromium things that you get on most Italian cars, sprayed with a light coating of black paint that might resist finger nail but not for long.

The fascia, the instrument binnacle, the door panels, the outer panels of the seats: all are in well stitched black leather. The central seat panels are knitted from plastics in an open design that encourages ventilation, the window winders are huge perforated metal cranks painted black and turning in the recesses that allow them to remain flush with the door trim; considering the length of the crank handle. I found the low gearing ridiculous and the stickiness of the action discouraging. By way of compensation there was some intelligent switch location, notable in the series of toggles mounted centrally at the top of the windscreen to control things like lighting and fans – the latter not only ventilating kind but also a Kenlowe for the water radiator. Actually there are two of these electric radiator fans, one switching itself automatically on and off by a thermostat; but Mr L C was using the other in traffic as a precaution.

Precautions were the order of the day, really. In the first place the car had to be delivered to England whole and unmarked. In the second place it had to be run-in, which was tiresome but unavoidable. All Lamborghini engines are given 24 hours’ running-in on the bench under their own power before installation in the chassis, but thereafter they still have to be nurtured carefully for a while. Our orders were not to exceed 5000rpm and generally to treat the unit gently as one would in normal running-in procedure. The peak of the power curve is at 7000rpm, so we were not too gravely handicapped, but it is rather galling to be limited to a miserly 126mph in a car that looks as if it ought always to be travelling at its easily achieved 176. With the 4.09 to one axle ratio that is normal issue the Lambo is so geared that when the engine is doing its 7000 the car will be doing 56mph in bottom gear, 83 in second, 116 in third, 144 in fourth, and 176 in fifth.

Lamborghini claim 300kmh as the maximum speed, which on this axle ratio would be equivalent to exactly 7350rpm – which is not too much for the engine, certain owners being known to have taken it beyond 8000 without apparent harm. Another way of doing your 300km/h, or 187mph, is to opt for the 3.76 to one axle which brings the revs down to a mere 6850 at that speed. The advantage is surely not worth the presumable sacrifice in acceleration, and the normal axle ratio is perfectly pleasant. Limited to 5000 as we were, we ran out of each gear at 40, 59, 83, 103 and 126 mph and at that we seemed to be crawling.

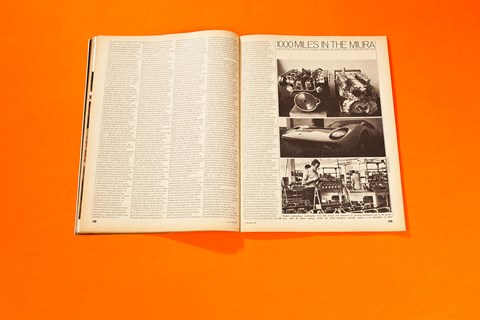

So we crawled away to the factory at Sant’ Agata where sundry papers were to be collected and a pair of wing mirrors fitted. It was a welcome opportunity to see the place where the chassis are built: and having seen it I can only say that if the Lamborghini engine and chassis are not the best made in the world they jolly well ought to be. Considering the small scale of production, the factory is tremendous. Its sheer size makes even more incredible the cleanliness of the place, the sort of positive, almost aggressive cleanliness that brandishes its fist at you as you enter, like that of a hospital or a dairy. The floor is some sort of red tile, the walls and ceiling are whitish concrete relieved by expanses of glass, with drawing offices and the like windowed along one wall of the huge single room in which all machining and assembly are done.

At one end is the machine shop, replete with nice clean, modern, but on the whole fairly unsophisticated machine tools. The other half was largely occupied when I was there by an over-head conveyor supporting a row of 400 GT 2+2 Lambo’s in varying and successive stages of near-completion. Alongside were racks of assorted components, all carefully colour coded, while in another corner Miuras were being put together at floor level in markedly smaller quantities. The place was not exactly a hive of activity, but if you looked hard you could find people at work on various things; there was the esteemed Mr Wallace walking through the shop with one of the engineers and looking fairly happy about everything, there in another corner was a customer discussing details of his inchoate 400, and dominating the entire place was a huge notice announcing to the workers that the closest inspector was the customer and that they had better watch it. A cursory look at the way the workers were working suggested that customers need not worry about the quality of the engineering they are buying. Whether they can feel as happy about the quality of the bodywork is, of course, an entirely different matter. It probably depends on the customer’s nationality – there are six British firms whose standards of carriage work are very much higher, but the Lamborghini bodies are probably as good as or better than any others.

After what seemed like ages, during which I was reluctant to smoke lest some ash get on that spotlessly clean floor, we left the factory and crawled away at our beggarly 120 on to the autostrada. Everybody seemed to be driving so slowly that morning. Fiats of all sizes, Alfas of all types were passed with such promptness that it seemed as though they were all playing a trick on us, driving around at a snail’s pace so as to kid us into thinking that were going fast whereas in fact we were crawling too. Weren’t we? It was so difficult to tell – there was no sensation of speed, no feeling of movement, no wind noise, no tyre noise. No shortage of noise either: the noise level inside the car is quite high, and the navigator should be a Stentor. But the noise level is more or less constant regardless of engine or road speed: a steady, mechanical mezzoforte made up of all the mumbling, thrashing, whining, whirring, groaning and grumbling metallic obbligati that a race-bred engine furnishes to fill the octaves left unoccupied by that exuberant exhaust. It is a lovely noise, an expensive noise, but I suppose when all is said and done it is a noise.

The autostrada was much busier than on the previous day, and although the road going Italians were still well-behaved there was a sprinkling of holiday-making Dutch and Germans who could not or would not use their mirrors. Oh yes, we made progress, and having a speedo calibrated in kilometres makes it seem rather satisfying to cruise at 200. But staying below 5000rpm in the Lambo is a bore, and despite the physical discomfort of being wedged between my luggage and the roof I went to sleep. All right, how many cars have you slept in at 126mph?

So we cruised on, up to and through Milan, along the lovely Ivrea autostrada, and then up the even lovelier hills towards Aosta. I was awake now, and taking interest; dull would he be who did otherwise in this breathtakingly beautiful country, where the foothills of the Alps provide lighting and colour and building and people and roads of surpassing interest. This was on the road that Mr Editor Blain and I had followed in the Elan so much earlier in the year, and I breathed a sigh of relief as we passed the spot where the Lotus had succumbed to its ignition troubles. All the same, my relief was tempered by a rising irritation: when the devil was this man going to let me drive?

Apparently various businesslike reasons made him want to be at the wheel while we negotiated customs barriers, and his idea was that I should take over once we had entered Switzerland. My first reaction was that this was a stinking rotten trick because I hate driving in Switzerland, and because I wanted to fling the Miura up the winding mountain road towards the Grand St Bernard so that I could compare it mentally with the wonderfully agile and controllable Elan S/E. However, I remembered that there were roads down the other side of the hills that were just as good, and some approaching the French border that were in fact more difficult; and undoubtedly I could see a lot more of this beautiful bit of Alpine Italy from the passenger seat than I could from the driver’s. So Mr L C was forgiven and when we pulled up soon after at an attractive Swiss hostelry only my desire to envelop a good bellyful of red meat and pasta could overcome my urge to get to grips with the Miura.

Maybe it was a very substantial bellyful, but for some reason I seemed to sink further into the driver’s seat than I had into the passenger’s. With the seat as far back as it would go, the wheel was at a comfortable distance – perhaps a little high and tilted away too far in the Italian fashion, but manageable for all that. The gear lever was perfectly placed, and had a lovely big wooden knob with a finger groove for comfort; but it worked in a very rectilinear gate, and was heavily spring loaded towards the plane of third and fourth. The clutch pedal was fairly heavy, which was to be expected; but dear Lord! The accelerator pedal was heavy beyond belief. You may remember that back in the days when the Hispano Suiza was the best car in the world its designers reached the conclusion that the brake pedal should require no more effort to make the car slow down at a given rate than was needed on the accelerator pedal to make it accelerate at a similar rate, wherefore the brake servo was invented.

Lamborghini appear to have approached the problem with the same object in mind, but from a different direction: they have simply made the accelerator pedal as heavy as the brake, instead of making the brake as light as the accelerator. To make matters worse the linkage to the throttles is terribly digressive. The first half-inch of pedal movement seems to trigger off an explosion in the engine compartment, and the next four or five inches serve merely to amplify this somewhat. I know there are 12 throttle butterflies to be controlled, and several accelerator pumps, and that they are all rather a long way from the pedal, but the whole affair is still ridiculously heavy. Oh well, it would help to discourage me from exceeding the rev limit – and I wasn’t really comfortable enough to start flinging the car around just yet anyway. I had to tilt my head forward and to the right to keep it clear of the roof, and in fact was not sitting square in the seat at all. Mark you, there is room to lower the cushion by one inch and the steering column can be adjusted for rake by dint of a few minutes’ spanner work, in which case the lofty Setright would fit into the lowly Miura pretty well, I reckon. Such modifications were scarcely possible in mid-Europe, however, and it was time we were off: so with a final reminder from LC that the car cost an awful lot of money and had to be delivered intact – we were off!

Not so fast. I stalled it. The pedals are heavy, and the clutched turned out to be as sudden as the engine. A second try with a few more revs took us smoothly away, and at last Setright was driving a car £25 dearer and potentially 25mph faster than any he had driven before. The change from first to second gear went through quickly and smoothly. If all the others were going to be like that I would have no complaints: there was resistance from the synchromesh, but only just enough. I let the spring loading of the lever do half the work of finding third for me, and getting fourth was much harder, for that spring is really powerful and it is impossible to cut the corners of the gate. Maybe the upward changes could be speeded by putting a bit of effort behind the lever to supplement the spring loading, I thought, going promptly from second gear to fifth in consequence.

Remembering that the Lamborghini has synchromesh for its reverse gear (which is opposite to fifth in the gate) so that it could be engaged while travelling forwards, I thoughtfully slid the blanking-off catch into position. By this time the Swiss had been alerted to the fact that there were a couple of foreigners seeking to drive across their previous country at high speeds without actually spending anything, and they rose up in force to prevent this dastardly possibility being accomplished. Mrs Castle would feel at home in Switzerland; so would dear old Fabius Cunctator. The first thing that the Swiss Defence did was to establish a traffic jam around some apparently non-existent road works, this delay enabling them to put up a few more speed limit signs. The netted effect was in fact to foil their obvious intentions, for although the hold-ups resulted in our reaching the northern shore of Lake Geneva just as the Montreux-Vevey-Lausanne traffic jam was building up to its evening peak I had by that time had so much practice in the difficult art of balancing an instant-engagement clutch against an instant-full-noise accelerator that we were more inclined to press on than to stop and let it all disappear.

Part Two

Although those first few dozen miles of snail’s-pace driving through Switzerland were miserable they were not overwhelmingly so, and we felt more inclined to press on than to stop and let it disappear. They also proved something about the Miura: that breathtakingly powerful engine is not so mettlesome that it will not endure prolonged idling or low-speed pulling. Once the clutch is fully home, the big four-cam V12 is completely and utterly tractable and will pull as smoothly and surely as a steam engine from tickover speeds in any of the three bottom gears. It does not overheat, it does not foul its plugs, it does not cough or splutter, it does not vary in the regularity of its idling.

Once away from the lake, gratification in the things that the engine does not do was replaced by delight in the things that it does. The winding roads over the hills to Valorb were full of variety, with lengthy straights, fast curves, hairpins, and all. The Miura reveled in it. As I began to use more and more power, the acceleration was beginning to verge on the incredible. Using the permitted 5000 in each gear it was seldom necessary to drop below 3500, and gearchanges come fast and free. Upward ones were pleasant enough, but downward changes were sheer delight. This high-revving four-litre was no discernible flywheel effects, changing speed with the sort of immediacy that we used to marvel at a decade ago when listening to the racing Gilera four-cylinder motorcycles. Approaching a 50mph corner from a 100mph straight was sheer bliss, the change from fourth to third going through like lightening punctuated by an immeasurably brief and incomparably crisp zip of revs. The brakes seemed just right for this kind of car and this kind of driving: extremely progressive in their response to the pedal, as sweet as honey if you pressured it gently and like a kick in the chest if you booted them hard.

However, such things are mere preliminaries for a corner and what really counts is the car’s behavior thereafter. What counted even more on this occasion was the feelings of the proprietor for the time being, who was sitting there obviously hoping that I would not do anything rash. This was inhibiting, but fair: after all, the agreed object of the exercise had been to make acquaintance with the car and not to wring its neck. In any case there is no greater sin in driving than to alarm one’s passenger (which, if I may say so, is why I most enjoy travelling with Mr Editor Blain) unless it be to alarm him in his car. We Setrights can bite the bullet, so I did not attempt to explore the farthest reaches of the Miura’s cornering and handling departments. Even so we did not hang about. At what felt like about seven-tenths for the Miura it simply went where it was steered, with no roll and no sensitivity to the use of throttle and brakes in the corner. There is not much feel in the rack and pinion steering, which is rather low geared and heavily damped, but it lacks nothing in precision and since it seems to have rather little castor action it does not vary much in weight.

Even though the fun was circumscribed, it was great fun nevertheless. Yet it could not last, for it was growing dark and the French border was near. Customs formalities for a new car being taken overland to England are inevitably more complex than the ordinary sort of touring transit and precious experience had indicated to LC. Esq, that the best time to cross this particular border was first thing in the morning. A couple of miles short of the frontier was a pleasant and clean little motel with a huge menu and there we halted. Early next morning, when what sounded like a couple of hundred cowbells stopped ringing so that it must have been milking time, we rose, and as the mists began to clear to reveal a grey and chilly morning we set off to cross France. For the same reasons as in France. For the same reasons as in Northern Italy, LC was driving. I just sat there and froze. It was a cold morning, admittedly, but we covered 20 miles before the engine’s oil temperature rose enough to allow spirited driving. The previous afternoon oil and water temperatures had been stable at 82 deg C, but then the sun had been shining and we inside the car were positively sweltering – that huge windscreen lets a lot of sun in, converting its due proportion of visible light into infra red in proper greenhouse fashion, and we had made the most of the half-dozen fresh air nozzles available.

This morning, though, all these nozzles were remorselessly tracked down and bunged, yet with every kilometer nearer to England and I felt more and more chilled. It was all right for LC – he is one of these Nordic types with glycol in the arteries, who breaks out in a sweat if somebody strikes a match but is apparently frost-proof. Personally I am more inclined to wear full tweeds in mid-Sahara and I could only conclude that the Miura, being a sports car, had no heater. This led me into an evil train of thought about Italian automobile engineers who never travel further north than Turin and probably winter in Taranto. It made me fume, which is one way of keeping warm; but then I took over the driving after an early lunch in Chaumont I discovered that there in front of me was a heater control. While LC was looking the other way I turned it on and engaged in a spot of rapid estimation and calculation to see how long he would take to slow roast at the usual 40 minutes per pound. I reckoned that we would make Calais before he needed to be turned over and basted, and warmed to my work.

Unpleasant work it was too, but through no fault of Lamborghini. Since mid-morning we had been driving through heavy rain in company with lots of obtrusive traffic on slow, narrow roads liberally set about with huge diversions. Every time we got away from one crocodile of cars and lorries we promptly caught up with another. Nobody wanted to let us by, and the limited vision available on the switchback roads made it hazardous to stay in the opposing lanes for long even with the sort of acceleration that the Miura could summon. Our route was to take us through Troyes, Soissons and Bapaume, and as we staggered on I could not help but think sorrowfully of the occasion a month earlier when in equally heavy rain I put 97 miles into the hour northbound from Paris in my own car. On this more easterly route our average was less than half that, and frequently less than a third.

Every so often the road would clear ahead long enough for me to give the car its head, and I was now using occasional bursts of full throttle to hustle it up to our maximum permitted speed. When treated to the spur, the Miura fairly rockets forward. There is never any hint of breaking traction, even on those streaming wet and bumpy French roads; just an unhesitating and almighty shove that suddenly leaves the mirrors empty. With folk and fuel aboard the Miura musters about 330bhp per ton, a figure that is worth comparing with that of some well-known Formula One cars at their starting-line weights. For example, the Mercedes-Benz in which Fangio won his 1955 world championship left the starting grids with 314bhp per ton; the Maserati which served him to the end in 1957 had 325; while of the rear-engined cars, Brabham’s championship winning Cooper of 1959 had 358, Hill’s ditto BRM of 1962 a mere 296, and even the beautiful little two-litre Type 33 Lotus in which Jim Clark performed such wonders in 1966 only figured at 364. Such a comparison is, of course, terribly approximate, for these racing cars had little more than half the frontal area of the Miura even if they were less streamlined; and in any case we were not able to employ full power, the full throttle output at 5000rpm being only about 84percent of the engine’s maximum potential. Even so, with perhaps only 280bhp per ton, the Lambo while being run in is obviously no sluggard.

There were times during these intermittent sprints when I wondered whether the chassis was really as fast as the engine. On Italian and Swiss roads 120mph had been plain sailing, but in France the bumps and camber made the car something of a handful at similar speeds. There seemed to be some bump steering from the independent rear suspension whose wheels are set with three degrees of toe-in at static deflection. Quite a lot of work at the wheel was sometimes necessary to maintain course on a straight road at three-figure speeds, and I was wholly glad that the situation was not further complicated by the sensitivity to gusting side winds such as we encountered from time to time. Occasionally the car’s headlong flight over wavy roads had to be checked as the suspension movement got in phase with the road contour and something bottomed with a nasty screech. The something later turned out to be one of the rear tyres making contact with the inner wall of the wheels arch at full bump.

All this I was prepared to forgive a little later when the Miura redeemed itself beautifully. We had gone rushing over a long hill brow at no little speed only to find beyond the crest that the wicked French wanted us to divert ourselves to the right but had not chosen to tell us in advance. With the right foot shifting smartly from accelerator to brake, the Miura was swung gingerly into the fork, and braked as hard as I dared as we shot down a wet concrete hill to a junction below. With the road still curving to the right, the sheer power of the brakes and the speed of the car at last overcome the grip of those very special Cinturati and all four wheels locked simultaneously. The car slid and wriggled; I backed off the pedal pressure by perhaps a fifth, and all of a sudden the tyres were biting, the car was under control, on course, and coming to a rapid and most commendable halt as the last bit of road curved away to the left. Inwardly damning the French and blessing certain Italians, coupled with the name of a New Zealander, I looked up and down the road we were to join, slotted first gear, and shot off into the rain.

It was really miserable journey, made worse by an appalling traffic jam in Bethune where we lost nearly an hour. A telephone call to Calais suggested that we had also lost any chance of a flight home, since we merely had an open ticket, so we trundled on into the murky twilight hoping that there might be a cancellation even though the number of holidaymakers heading in the same direction and cluttering up the road made it seem improbable. We could not help recalling the Bradford boy racer who had accosted us shortly after we entered France when we were held up behind him in a traffic queue. Where, he wanted to know, are you headed – Calais or Boulogne? As though there were no other conceivable possibilities. But we thought more cheerfully of him upon arriving at Calais Airport, wondering if by a poetic chance his might have been the cancellation that enabled us to travel on the day’s last plane to England.

During the final leg of the journey home from Southend to London, with LC at the wheel, I had time to reflect on what I had learned of this unique car on this unusual trip. Of one thing there could be no doubt: that engine is absolutely superb, In terms of performance the car has little to fear from anything else anywhere. How much of its performance can be used is more debatable; as I have explained it was simply not on to try cornering conclusions, but the car did feel skitterish on French roads and the steering is perhaps too low geared. At night the lights are only good enough for perhaps 90 or 100mph, giving plenty of spread but seeming to have little range. The pilot lights on the instrument console are angled downwards, forsooth, and cannot be seen in daylight, and there are several other details of interior appointment that could well be revised. There is virtually no stowage for odds and ends for example – just a little shelf ahead of the passenger which would not only not accommodated Mr B*dd*’s Rollieflex but would not even take my Zenith, though it would presumably be spacious enough for a Minox. Still, if you wanted a practical everyday car you would not be spending £4025 per seat. In fact unless you are a rabid go-it-aloner you will not buy the Miura as your one and only car.

As part of a stable, however, this dramatically conceived Lamborghini can be employed for what it is – an immensely fast, modern two seater with the world’s finest engine, society’s highest cachet, and plenty of scope for further development. It may indeed be that Lamborghini would rather not have been pressurised into selling into the Miura so soon. It is really still a prototype, but one which is already undisputed master of the road.

Since committing all this to print I have had the opportunity of driving another Miura, one that had already covered a fairly substantial mileage in the hands of one of our most esteemed readers. It is only fair to say that this car had a much lighter accelerator, a bit more headroom, and a bit less synchromesh. At least it was thoroughly run in, and it was a real pleasure to let the engine have its head instead of curbing it at 5000rpm. The 2000 beyond this limit come up very quickly indeed, as is only expected when you consider that the peak of the torque curve is at 5100rpm.

Another gratifying thing about the Miura is the confidence it instills. Having driven one fairly slowly, I had no hesitation in giving this second specimen full throttle in the first four gears as soon as I was at the wheel. This for me is most unusual, for I usually like to play myself in fairly gently even in cars to which I am no stranger.

Alas, I still have no idea what 180mph is like. I only had a car for a few minutes during a photographic session on a narrow and somewhat short country lane – certainly not the long kind that has no turning. Even so, the thing got up to 120 in fourth before I had to turn back to remain in the photographer’s view. According to Lamborghini this should take 18sec, but I had the advantage of a downhill start – and if you want to try high living, let me recommend the experience of unleashing 350bhp downhill and then changing up! Free-fall parachuting probably gives the same sensation at a fraction of the cost, but driving the Miura is more comfortable and the terminal velocity is appreciably higher.

Read more CAR adventure drives here