This limited-run, lean-and-hungry Lancia Rally is no exotic car. It is a pure homologation special. It was built to have two properties: traction and manoeuvrability to beat a rally-prepared Audi Quattro turbo, and an instant, supercharged response to the throttle. And it delivers both.

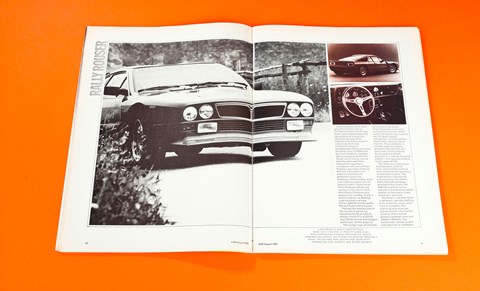

Lumps, bumps, scoops, slats and a huge black spoiler. Mandatory red paint glinting in the weak and intermittent spring sunshine of a Turin side-street. The 1982 Lancia Rally rasped its way from beneath the interconnecting walkway that links the two halves of the Fiat-owned Abarth plant. After hours of negotiations an exciting portent of the sporting ’80s was ours to drive for an afternoon; just one of 207 new mid-engined two-seaters built to ensure that, post-Stratos, the Lancia name stays to the fore of international rallying in the coming decade.

It has to beat the four-wheel-drive Audi Quattro and another turbocharged pioneer of the way rally cars are developing in the ’80s, the mid-engined Renault 5 — never mind the why-are-we-waiting? Escort Turbo with rear transaxle transmission a la Porsche 924/ Alfa Romeo Alfetta, and a host of other way-out Group B homologated cars that other manufacturers are developing. Lancia had to make 200 cars to be eligible and that means there will probably be fewer than 150 Rallys available as road cars; the rest are reserved for factory rallying needs.

The car safely in our hands, we wheezed gently away to a handy photographic location, and a chance to study this fascinating technical marriage. It is an alliance between the modern mid-engine and the revival of one of the oldest routes to extra engine power: the mechanically-driven supercharger.

Supercharging and its comeback will be no surprise to those familiar with developments at the recent Turin Show (CAR June). Together with four-wheel-drive and turbocharging (where the exhaust gases provide the energy that pressurises fuel mixture induction), supercharging was hot news in Turin, particularly as Lancia also had the far more modest —though yet unavailable for road testing — Trevi thus equipped. But for motor sport purposes supercharging has been dead since the ’50s. Why revive it when turbochargers are providing ever more fantastic, and flexible, outputs? In categories as diverse as Grand Prix racing (circa 600bhp from 1.5Iitres) to rallying (330bhp from 2.2litres, or 260bhp from 1.4litres) the turbocharged petrol engine sets the pace.

It is because power, sheer brake horsepower at least, is far from being the only requirement in a rally car. Torque, instantly available for a corner that deceives, or a sequence of 50-90mph bends, is priority one in a top-line rally motor. It must be flexible enough to drive on public roads and yet provide heart-pounding acceleration at the split-second a driver demands it. Even those dedicated engineers at Audi with their intercoolers and complex back-up systems have failed to provide such qualities in their Quattro.

The Audi gets better all the time, but those most intimately involved freely admit that it would be better with a normally aspirated, bigger capacity engine. Renault suffered such problems in Formula One racing, where they could not initially qualify on tight circuits like Monaco with their 1.5litre turbos. In rallying, the R5 mid-motor magic is best delivered where the way ahead has been thoroughly learned, using a pace note system. Tackle a road full of unknowns, such as Britain’s RAC Rally, and suddenly the R5 Turbo driver discovers he needs his power now; more quickly than he usually can get it.

Those who know their Ferraris will be acquainted with the name of Ingegnere Aurelio Lampredi. From 1946 until he left for a Fiat production engineering job in 1955, Lampredi learned how to apply his previous aero engineering talents to the frontline battle that was to take Ferrari ahead of Alfa Romeo in Grand Prix racing. He did not always use superchargers, indeed Ferrari proved the worth of large unsupercharged motors repeatedly, but Lampredi was always well aware of the low-down power, akin to doubling the cubic capacity, that supercharging could swiftly provide for his drivers.

In the late ’70s Lampredi was to be found working beneath the Scorpion emblem that Carlo Abarth sold to Fiat along with the rest of the Abarth motor sporting and conversions company. Once again the supercharger was emerging for serious consideration. There were mild performance versions of Fiat’s 131 (the twin overhead camshaft engine was Lamprecii’s baby in 2.0litre, 16valve guise) with 130bhp supercharged, plus engines providing around 200bhp that had a clear competition intent.

The result of all this background work provided a 16valve Fiat Abarth twin-cam engine with perfect road manners, yet a healthy power peak of 205bhp at 7000rpm. The cleanly-delivered horsepower is reminiscent of the best fuel injection systems, yet the long stroke (84x90mm) engine is pressure-fed by a single Weber 40 DCN. The competition potential is 310bhp and lots more torque, using fuel injection within the rallying specification.

The Abarth-developed supercharger has a two-lobe mechanical compressor within and is belt-driven from the nose of the crankshaft. In this mild-tune roadgoing role it is asked to provide little more than 7.Olb/in2 boost to a cylinder head operating on a 7.5 to one compression. That is enough to bring the kind of generous torque curve many heavier 3.01itre engines fail to supply. From 1500rpm to just short of 3000rpm the torque value ascends rapidly, which makes the Rally a very easy car in traffic. Yet maximum torque of 166lb ft is not reported until 5000rpm, emphasising the broad spread of pulling power. To put that in normal production perspective, the dimensionally-similar injection 2.0litre sold in the Lancia Coupe and HPE provides 122bhp and 1291b ft of torque. That is how effectively this roadgoing supercharger installation performs in practice.

Other design features that demand attention include the use of twin gas dampers each side of the rear suspension. They are just part of an independent wishbone system that can be manipulated to transform the suspension from that of Safari sand scrambler to racing tarmac tearaway within minutes. Basically, Pininfarina constructed the body by grafting tubular frame extensions to a lighter and stronger Lancia Monte Carlo cockpit. Unlike the Monte Carlo the Rally’s twin-cam is mounted north-south with a ZF five-speed transaxle and 25percent locking differential aft of the engine. Why? So that rally mechanics can service it faster than is possible around a transverse layout.

Exterior panels are in stout glassfibre for the road car. Pininfarina claim an 0.37 drag factor, reasonable despite the late addition of a huge (but optional) rear spoiler for stability and traction reasons. Lancia say the mixed construction body is exceptionally strong, surviving drop tests up to 12,000lb and 6g. Such durability, together with an exceptional result in 30mph crash testing, can be partially attributed to the integral roll cage that is included on all Lancia Rallys. Padded cage tubes embrace the roof, front pillars and extend to provide side protection across the doorways. Unfortunately, even such rigorous protection can meet its match. Works driver Attilio Bettega suffered leg injuries in the Lancia’s first World Rally Championship appearance last May. It was a double setback, as Bettega surprised both a private Ferrari 308GTB and the works Renault Turbo with his pace.

Perhaps the prettiest part of the car are its gleaming Speedline 8Jx16 and 9Jx16 wheels. Pirelli P7s of 205/55 and 225/50 section (the biggest at the rear), do the gripping. The cockpit says all that can be said about the Italian alliance between machismo and sporting machine. At the outset, the layout says ‘Look at me, I’m about serious competition.’ All three pedals are drilled in best racing car manner. The accelerator is suitably large and ideally placed to heel-and-toe; the gear lever is fairly long but moves with marvellous precision in a narrow, fool proof pattern — first opposite reverse, fourth opposite fifth.

The seats are a marvellous amalgamation of Italian style, red pinstripe on black cord, and honest-to-goodness comfortable location. The black mood is carried into virtually every item of trim, particularly the generous acreage of the simple, flat, matt facia and the centre console in a distinctive rubber similar to that used to make skindivers’ wet suits.

The Rally’s instrumentation is generous, perhaps baffling to an unfamiliar driver, but it soon is accepted. The matching large dials are placed smack in front of the driver to inform him of progress between zero and 260kph (162mph). The tachometer carries no limit indication for its 10,000rpm scale, but we exceeded 7000rpm, the power peak, only once. Supplementary instrumentation covers not just the expected oil pressure and water temperature, but continues its white-on-black clarification with oil temperature and supercharger boost pressure. The latter reads to a maximum three times beyond the road going maximum boost—to 1.5 atmospheres. The centre console is taken up with pop-out blown fuse indicators and the gearchange.

When hot, the engine fires almost instantly— at the turn of a key rather than the push of the button which Lancia, with their competition background, might have been tempted to use. The engine burbles and chuffs at between 1200 and 1400rpm, its slightly uneven running shaking the tail of the car just a little. The engine has the crispness of the usual loose-tolerances competition unit, but there isn’t the clatter you might expect. That supercharger seems to quieten the engine to a degree when crank speeds are low.

The ZF gearbox chatters when the engine idles and the lever is in neutral but that stops when you push the fairly heavy clutch pedal (how good it is to have pedals with plenty of surface area) and snick the lever into first. The clutch, fairly heavy, has a beautifully sensitive take-up. No judders or jerks, just smooth metering of the power— even when it is abused with a 6000rpm start.

The engine, rorty and rasping throughout its range conveys its power so efficiently — and the car itself accepts 205bhp with such ease —that it can deceive you into thinking that it is not quick at all, never mind its engine output that exceeds 100bhp/litre. There is no sudden push in the back or feeling of the engine rising ‘onto the cam’. There are two overhead camshafts, 16valves and a supercharger, but there’s no shrill compressor whine (until the car is powering in the high gears above 80mph), no bad manners at all. This engine runs much like the lower-tune 122bhp job.

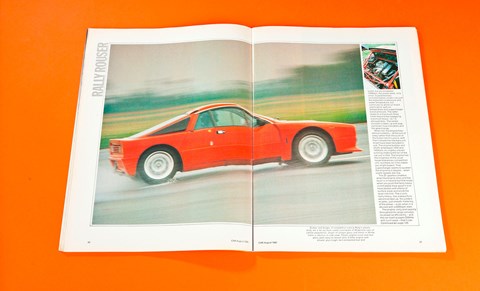

So you pit the car against a stopwatch on an apparently endless straight, wide and well surfaced. It’s then you find that the claimed 7.0sec from 0-60mph is slightly conservative; your own stopwatch will read 6,8sec even after you’ve corrected the speedometer error. It will run easily to an indicated 205km/h, converted and corrected to a true 116-118mph but will accelerate only gently from there. This is a 125mph car, with the last of the speed available only on a very long wind-up. On the other hand, the car will show 180km/h (110mph or so) on quite a short straight.

If you try and baby the Rally on a fast start it will likely bog down, such is the grip of its huge P7s and the comparative softness of its engine below 3000rpm. Get tough, hand it 6000rpm and it spins its rear rubber momentarily, recovers and rockets away, the revs never falling below 3500-4000 (it’s hard to read the dial accurately in the rush). But your departure is abrupt. The standing quarter mile is dismissed inside 16sec and the engine—with 7000rpm as its limit— stretches for 40mph in first, 60 in second, 90 in third, and fourth produces 118mph. That’s the practical fifth maximum, too; though a really long straight will produce more.

At first, it seems that this car’s equipment— corduroy seats, door linings, coarse carpet; dammit, even facia vents — smother its competition intent, but it is not so. The noise — burble at low revs, clatter and snarl at higher speeds — is more (and more inspiring) than the run of road cars and the build-up of cockpit heat shows that the elegant through-flow vents are far from adequate. You must lower a window to keep cool on mild summer days, even when the breeze you’re generating is doing 100mph. And the rattles from the easily-flexing plastic bodywork, frequent on rough Torinese streets, regular on occasionally-rippled Italian autostradas, wouldn’t do for a purpose-built road car, either.

Yet the comfort of the ride (plenty of clearance; superb damping, surprising travel) is quite as good as the most superior sports cars. You need only keep at the back of your mind the need to protect your low, cow-catcher of a nose spoiler. Wind noise is quite low and the car needs less than half throttle (and half noise) to propel it at 100mph.

Yet speed in a straight line is not the reason for this car’s existence, You know full well that it is built for manoeuvrability and reliability and strength and stamina, the elements needed in a top-flight European rally contender. Put some authority behind your steering and braking commands and you learn that the more. The steering, always firm, almost heavy at low speeds, is absolutely pin-sharp. You can literally deaf out road in inches, yet the system (rack and pinion) is high-geared enough for you to swing it well into either lock, quick as you like, Further, its responses are sensitive and accurate even when there’s lots of lock on, which isn’t always typical of even the best exotic car systems.

The Rally corners dead flat (firm springs, stacks of grip, big anti-roll bars, low centre of gravity) and its superior suspension geometry controls the fat, low P7s so that even maximum effort cornering has zero scrub effect on the tyres’ shoulders. The rear tyres on the high mileage Rally we drove (we had two, new and `used’) were thin, though, and didn’t respond well to hard cornering on wet roads. The tendency of the tail to snap out without delay gave us reason to praise the quick-reacting steering. Mind you, these reflexes are built into the car at the expense of any kind of steering damper; the kick-back over bumps is of unhappy proportions at times.

The brakes, always strong, work according to one of the most progressive pedals in existence. The effort always seems appropriate for the conditions. On one hand the car needs little effort for gradual stops, yet it needs decisive pushing for fast action. But senseless mashing of the pedal in panic situations doesn’t lock everything instantly solid. It just stops.

As for the chassis behaviour, the grip must be in the 1.0g league, the lean as mentioned is as modest as many a pure track car and the handling is widely and almost instantly adjustable. Approach a bend a shade too fast, power early and the car will understeer across the apex, not far out of line but enough for it to be an unsatisfying exercise. Such is the precision of this steering that untidiness seems amplified in your hands. Get your entry speed right and the car will turn in exactly to the degree that you turn the wheel. A squeeze of the accelerator, a reduction of lock, a snarl from the engine and the car exits with real speed, near full noise, perhaps a whisker out of shape. Oversteer on bitumen frequently cures itself; the more persistent kind can be contemptuously cured with a flick of lock.

Jab the throttle at ridiculous points on a test track handling course, just to try and upset the Rally’s composure. You discover that this is the ultimate in forgiving sports cars. You can get as broadside as you like, as often as you like, and the Rally just seems to find a little more adhesion to resist the finally inevitable tail spin even under full second-gear power. There is absolutely no trace of mid-engine snappiness under duress. Sadly, the price is that tick-tack, sharp-jinking ability of the short wheelbase Stratos, so suited to Mediterranean road rallying, but now just a memory. It is replaced by efficiency, comparatively heavy steering in low speed corners, and traction that will make this a hard car even for Audi to beat away from a standing start.

Weighing 2574lb in road trim, distributed 43% front and 57% rear, the power-to-power ratio of the Lancia is not dissimilar to the Lotus Turbo Esprit, yet the two could not feel more individual. The Lotus on paper has performance that is totally superior. But the Lancia leaps to any traffic gap so fast through its immediate, supercharged response, that it may well be a whisker faster over a traffic-infested route.

Any confrontation between the Lancia, 207 examples of which have been made, and the equally rare British supercar — about 170 Lotus Turbo Esprits had been built by the beginning of 1982 would be a tantalising grudge match!

Read more CAR+ iconic car features here