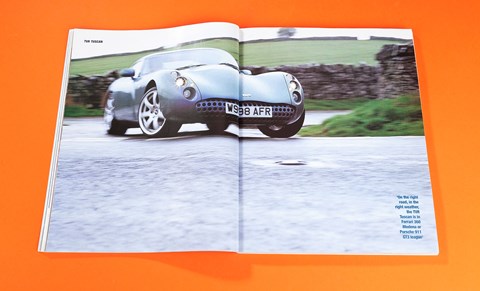

This car will hit 60mph in a shade over four seconds. On some roads it will be a match for Ferrari’s 360 Modena. The price? £40,000. Say hello to TVR’s eminently sensible Tuscan.

The calendar says spring but the skies say monsoon and every road for five counties around is irrigated to absurd excess. Who’s that bearded bloke we just passed, building a big wooden boat in a field? Why are all those animals lining up two by two? This is definitely not a TVR sort of day. In any case, I wonder if I’m really a TVR sort of person. All that power, fine. But the defiant rejection of driver aids? I’m not sure if I can carry off the swagger, the implied speech bubble above my head: ‘I can handle it, me’. Still, after two and a half years of waiting, it’s time to test the Tuscan for real. Time, possibly, for me to brace myself and take a long, deep draught from the chalice marked poison.

Two and a half years? Those about to take delivery of a Tuscan first signed their deposit cheques in 1997. Presumably they still have use for a two-seat sports car despite having had to wait long enough to have grown old, spawned several children or become a high court judge. Back then, it wasn’t even the Tuscan shape they were ordering, but something called the Griffith Speed Six, which — surprise! — put this new straight-six engine into a modified Griffith. But in the aw-shucks, one-thing-led-to-another way that makes TVR so endearing, the vision became more than that. Chairman Peter Wheeler wanted to make a very fast GT car that could be used every day, so the chassis changed to improve the ride, and the body design became a coupe that could be half-stripped, rather than a full roadster. It allows the car to look after you better against weather like today’s, and also if you invert it.

Straight off, the engine fits the brief. Its figures predict what our later experience shows, that it’s perfectly capable, in a car this light, of being savagely fast. But for now we’re in conditions that mandate subtle, controllable delivery, and it’ll give that too. The lightweight end of its throttle travel is as progressive and friendly as a BMW M3’s. Not that it hums like a German straight six, mind. Turn the key (yes a key: after all that messing about with buttons, TVR has acknowledged that a key isn’t such a bad idea) and it in-flames into a nice chattery, poppy idle, like some breathed-on old Jag. There’s a certain volume of sound, then, but it won’t frighten the horses.

Put a few hundred more revs on, and it has straightened out nicely, the happy mechanical balance of the in-line six playing off against a two-channel woofle from the tailpipes. Ask for more and that exhaust hardens in direct proportion, the sound simplifying itself into a searing no-nonsense chord. Other engines — you-know-who’s flat-sixes, V8s of whatever crank angle, V12s assorted — may choose a sound signature to mark their layout. But by the time it’s half-way working, this one doesn’t sound like six cylinders, it just sounds like the power that it’s so spectacularly delivering.

But for all that force, what puts this engine up in the premier division is the connection between you and it. The throttle pedal itself has a long travel and is perfectly able to translate the slightest increase in foot pressure into an exactly measured increase in urge. Factor in the spike-free output curve and you realise that if the Tuscan does catch you out with its performance, you’ve only yourself to blame. The time dimension is just as taut: response is as instant as you can detect.

This is stage one in building a relationship with the Tuscan. All the points of contact are like this accelerator. The gearshift and clutch, though heavy, are exact. The brakes act in perfect ratio to pressure. You don’t notice them when you’re dawdling because there’s no suddenness to the pedal, but when you want more they bite just so. And the steering has the same urgent proportion.

But at the moment I’m just skirting fretfully around what the Tuscan can do. The test car is on optional 18-inch wheels (16s are standard) carrying 225/35 tyres at the front, 255/35 behind. Pushing that through the water is just 1100kg of car. Even on the M6, we’ve been aquaplaning at 70. The Cumberland moor roads are deeply puddled, randomly turning into fast-running streams. Even when the tarmac’s merely wet, never mind submerged, the front brakes are easily locked. Anything like full throttle, even in third and at moderate revs, will spin the rears in a straight line.

But gradually it’s clear that you can nibble around the imposed limits. That almost telepathic engine control, it turns out, is matched by the chassis. Through and out of a bend, you can ease more and more out of the throttle, ekeing the rear tyres until they’ve no more grip. The Tuscan lets you know, unambiguously. So you feather back just a fraction, maybe go easy on the steering lock, and head on down the road. If you fancied it, and you couldn’t foresee deeper water a few yards down the road, this would be the moment to do the full-on tailslide. There’s no doubt careful damper tuning has found more wet traction than a car with this much power, and this little weight over the rear tyres, has a right to expect. But it’s equally clear that with its extra traction and its electronic aids, a 911 would be simpler and faster, right here, right now.

But when the sky clears, we can delve more, pouring more stress into the brakes and corner entries. The Tuscan really bites its way into a curve, the front end carving flat and sharp as you first roll your wrists on the wheel. From where you sit, back at the rear axle, the nose is distant, so the feeling is of it peeling sideways, rather than of the whole car pivoting. But it’s a definite, satisfying motion, and the rest of the car follows it all-of-a-piece, building force and the communication of it. There is some roll in this set-up designed to be tenable on wet or bumpy roads, but away from the duress of a racetrack the body control is just fine, and the dry grip colossal, although very, very much throttle-dependent at the rear, and always with that wonderful feel and control of the moment when the back steps out.

The ride remains as good at speed as it has been all along, matching firm springing with a filtering of harshness and quenching of resonance. If you’re not looking out for it in a road-testerly way, you never really notice the ride comfort, and in a car this quick that’s an achievement.

And the performance, once there’s the purchase to use it, just beggars any British secondary road. In the wet, 5000rpm had felt like a natural limit, even when the road opened out towards infinity, but it turns out there’s no particular power-step between there and seven. There’s just more, much more, of the same strangely paradoxical melding of full control and explosive insanity.

Never mind the power, just a view of the Tuscan’s interior can be a shocking experience — a jolt, a slightly scary challenge. It’s anything but comfortable looking, full of shapes and objects that are hard, intimidating to the eye — and hard to the touch too. TVR’s not making things easy, but when did it ever? Instead it’s making things different, poking around with brave ideas. Given time, some of the ideas might become new conventions, others get cast aside as cranky. Right now, we can’t tell which will be which, but the first task is simply to get to grips with what’s here.

TVR first launched its dashboard treatments into a parallel universe with the Cerbera, which hangs its separate dials like Christmas tree baubles around the steering column. The Tuscan goes further. Fixed above its steering column, and hinging up and down with it, is a single compact aluminium binnacle, clad in leather, faced in brass. The speedo is a long, willowy needle that tracks around a semicircle across the entire upper perimeter of the field, the backlit numbers cut out from the brass. The middle portion of this real estate is occupied by a big LCD readout, and you can cycle through just what you want it to show you. Most people will no doubt opt for it as a rev counter, but the fact that this car doesn’t have a permanent tacho shows how TVR is prepared to tilt at windmills. You get, full-time, a set of change-up lights on a flying bridge above the binnacle, plus a limiter, so you won’t over-rev. Beyond that, you’re meant to use your ears and your sensitivities to time your gearchanges. When the Tuscan is at full noise, the digital screen tacho simply changes too fast to be read.

Other choices for the LCD include oil pressure and temperature and volts. And if any reading goes critical, it’ll switch the display to tell you. Fuel and temperature get full-time analogue gauges. Mind you, needles have been deemed too ordinary, so instead little fan-shaped aluminium shutters pivot their way across the scales. Believe me, it may only be a fuel gauge but it reminds you that mankind’s eternal struggle for self-validation through creative endeavour is not a wasted one. Someone at Blackpool thought it might be worth re-inventing everything in this life, even a fuel gauge. And they were right.

The designers say this dials-and-readouts arrangement is compact, and that it can be easily be unplugged and replaced with a new one if maintenance is needed. That it looks — and materially is — so different from a conventional car’s dial-set, is a result of TVR’s manufacturing philosophy as much as anything else. It’s made right there in the factory, so TVR gets a radical product for low up-front investment. The price of the car can then be set at a level that covers the manufacturing costs, however many the market ends up demanding. Simple economics, really. And it frees up development cash for the engine.

Spreading out from the instruments, the cock-pit doesn’t get any more ordinary. The stalks are solid aluminium, and have a slightly sinister sharp curved profile — nothing in this cabin is straight, and designer Damien McTaggert claims influence from futurist sculpture, but it could equally well be a nod to Philippe Starck. The heater and window-winder switches are machined aluminium rotaries. The eyeball vents and ashtray are turned from solid brass. TVR won’t stand for buying in old Metro or Fiesta vents and switches, so it’s faced — as with the instruments — with two choices: tooling up its own in plastics (a vast investment that only serious spotters would appreciate) or making each item practically by hand. It makes the cabin of a TVR a very special place to be. These controls and vents and the fabulous LED rear indicators look and feel true to what they are jewellery, lovingly crafted.

At either end of the dash are drilled aluminium brackets that hold the full-width shelf in place. The door handles are made of the same stuff, and the handbrake, the gear lever. So are the pedals, which floor-pivot from an industrial-strength assembly glinting away in the footwell. Your posterior is planted on a seat of exaggerated contours, supporting in the right places when the car gets going. You’re sat upright, and the windscreen is similarly vertical. This is in no sense a laid-back car, but this is a sensible way to drive, good for visibility. It’s practical in the same way as a 911 driving position is practical, and it emphasises the Tuscan’s remit as an everyday device.

It’s when the roof’s on and you’re in everyday mode that the grouches surface. No unexpected nasties, mind, and fewer of the expected ones than you might expect, if you see what I mean. This is a low-volume sports car, and the roof comes off. So snaldng around the cabin is a border of old ugly rubber sealing strip. Its oldness and ugliness I’d tolerate, if only it sealed, but it seldom does. There really is no alternative for proper, bespoke sealing rubbers, but tooling them is prohibitive. Hence motorway wind noise from just by your ear, varying from the irritating (roof panel nicely bedded down) to the intolerably raucous (roof panel fitted in a hurry because it’s started to rain). TVR’s boldness with electronics isn’t quite yet match by infallibility: the speedo cut out sporadically, and the TVR Car Club’s internet e-group shows that several dealer demos and early owner cars have had the same. Other quality itches? Some of those brass vents glide around like butter meeting Teflon, while others grate and jam. Don’t ask me why. Outside, the body-colour cladding on the screen pillars refuses intimacy with the matching section of the roof.

The roof itself is a light and manageable panel that jams under the boot lid. Getting it there isn’t a quick job, but it’s worth it in the summer, especially without the optional air-con, when you’d be autoclaved by the engine’s heat soak. The roof is light for the same reason as the rest of the body: It’s a honeycomb glass mat, new to TVR, that gives a lighter, stiffer panel than ordinary mat.

The bits you see, the body and cabin, are what’s newest about the Tuscan. Its engine has been on the streets for a year, in the 2+2 Cerbera Speed Six, and so has the chassis, tough here it’s shortened in wheelbase because the Tuscan seats on the two. A lot of work has gone into the chassis tuning, but the Cebera’s hardware was deemed by TVR as the most appropriate starting point for a car that was meant to be fast yet sophisticated. The Griffith and Chamaera roadsters, simpler hot-rods, ride on a previous generation of chassis. The principle of all of them is the same though: a load of steel tubes welded up on-site into a backbone lattice, with stout double wishbones at front and rear. Anyone handy with a welder would be able to make you one up.

TVR has never entertained the notions of ABS or traction control. They’d detract from the pure driving experience, y’know. Yes, and we know they’d cost real money to develop, as would the airbags whose absence becomes more and more conspicuous as each year passes. The TVR book of safety reads like this. You’re responsible for your own your own actions, and if you crash, the frame is very strong, as racing experience has proved. Wheeler, contrary to the views of any safety organisation you care to name, believes airbags have hurt more people than they’ve saved, and anyway the Tuscan doesn’t have particularly subtle crush management, so deceleration will be rapid. Make sure your seat-belt is tight.

The engine is always there. It’s not just the noise of it, the ever-ready propulsion. It’s the heat of the thing. The six has been rammed right back in the chassis frame,- its forward end behind the front axle, its flywheel at about knee level. Its heat, which gushes out through the centre con-sole and foot wells, braises your feet and, through the metal gearlever, chargrills your shifting hand.

But then the engine is the point of the car. If you’re the sort of car maker that’s obsessed with ridding your cars of other maker’s air vents and lamp clusters, you certainly won’t contemplate anyone else’s engine. I don’t mind admitting I thought the cost of developing, homologating and warranting the AJP8 would kill TVR (probably because I was reckoning it would cost what big car makers feel they have to spend, but TVR finds ways to be thrifty). That never happened, and now it’s a second in-house engine ahoy. If a big straight-six in a rear-drive coupe puts you in mind of an E-type or DB6, that’s okay. But why a new engine when they already have the V8? Output is similar, so’s the weight. It costs only a little less to build. In the end, there’s no rationale. Wheeler just wanted to, that’s all.

But the six, now it’s here, does have different characteristics than the eight. It’s more refined, for a start, and the delivery is chalk-and-cheese. The V8 goes big on torque, ready to light over-steer fireworks at any time. The six is revvier, not arriving at peak torque until 5250rpm, and the full power of 360bhp at 7000. This puts a safety catch on the car’s full, shattering performance. You’ve got to be very deliberate about asking for it, summoning low gears and big crank speeds.

Making the engine short pushes the weight back in the car and extends the front crush space, so make it short they did. Most ancillaries sit alongside the block, and the camshafts are driven by compact chains. They act on the 24 valves via low-inertia finger followers. Like a BMW M engine, there are separate throttle butterflies for each cylinder, which means mixture control for each one is just so, and every cylinder gets its dose of fuel and air right as you push the pedal. Dry-sump lubrication allows the engine to sit lower, and means it’s looked after when owners take it to track days and start sustaining big g-loads.

Despite the fact that it towers over your every thought about this car and your every sensation of it, the engine is permanently hidden from view. From the cabin, the bonnet drapes itself shamelessly over the straight six, then dives down and forward into two deep chasms which gush out the heated air from the radiators. But you can’t lift this bonnet. That’s the ‘service bonnet’ you see, and it’s bolted there, so it can be made lighter. The ‘owner bonnet’, giving access to fluids, is ahead of it, accounting for the figure-3 cut-line half way up the front of the car.

TVR continues to compete simply because it won’t compete with anybody. In price, layout and practicality, the BMW M Coupe is it. But the BMW is softer, slower, vastly more refined. On the right road, in the right weather, the Tuscan is in the 360 Modena or 911 GT3 league. It has a sharpness that a standard 911 or DB7 Vantage don’t even aim at. But to talk about what competes with it, you need to introduce the vulgar topic of money. The Tuscan is £40,000 and that makes its appeal simply unmatchable. To do that for the price, and still provide practicality, leads us inevitably back to that paragraph of quality grumbles above. But it’s only a paragraph, and no TVR owners are surprised when they come upon the same thing. Accept that and poisoned chalice becomes addictively potent cocktail.

The specs: TVR Tuscan

Price: £39,750

Engine: 3996cc dohc 24v six

Power and torque: 360bhp @ 7000rpm; 310lb ft at 5250rpm

Transmission: Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive

Suspension, front and rear: Double wishbones, coil springs, anti-roll bar

Tyres: 225/35 ZR18 (f), 255/35 ZR18 (r)

Weight: 1100kg

Performance: 180mph, 4.2sec 0-60mph

Read more from the iconic cars archive