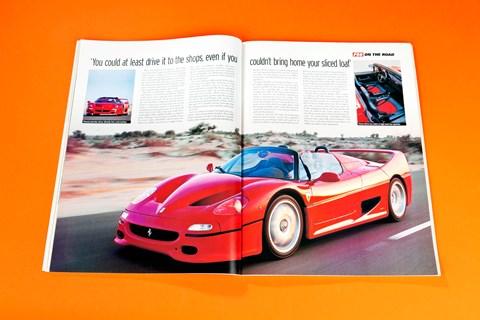

► CAR’s first ever Ferrari F50 drive story

► ‘The noise? A shattering Monaco-tunnel howl’

► From the March 1996 issue of CAR magazine

Well, I guess I would enjoy telling you what a crazed high-wire ride the F50 was. How I had to take the brute by the scruff of the neck and bring my every last drop of skill to bear. How I probed the far edges of the envelope and lived to tell of hallucinatory speed on a knife-edge rock’n’rollercoaster battle between its satanic nature and my rapier reactions. Affecting a casual raise of the eyebrow, I could gently hint that, yes, it sure does bring the F1 experience alive on the road, delivering unmatched power and thrills to wheelmen of the calibre of Alesi and Berger and, ahem, yours truly. And if pressed, I’d quietly hint that if such challenging responsiveness brings with it the risk of making things just a little too tricky for ordinary mortal drivers, well, that’s just the way it has to be.

But I’d be lying if I did. It might have 520bhp, it might be made of carbonfibre and Kevlar and Nomex from tub to gearknob, it might have 335/307R 18 tyres out back, but the F50 honestly is a bit of a pussycat. It bestows on a driver of merely ordinary abilities (self very much included) a taste of something sublime, without scaring you or, conversely, removing you from the action. There’s no power steering, no traction control, no four-wheel drive and no four-wheel steering — not unless, during a tight bend, you opt for it via the rear-axle lateral kinetic activator that lies beneath your right sole. No doubt certain other cars cover the ground more quickly in difficult going, but none of them will electrify your smile like the F50 when the conditions are right.

Ferrari didn’t even go in for the top-speed race with this one. A standard McLaren F1 has another 107bhp. The F50 gives it 30mph at the top end. And the F1’s torque curve indicates a fat helping of extra shove in the lower rev ranges, too, variable cam timing and all. Ferrari’s designers made a simpler engine, aimed at sheer howling, high-rev, track-attack scream, and as its long, blue rev needle flicks across the yellow and into the red at 8500, 160mph in fifth, I can hardly imagine a better job being made of it.

Back last summer, when the press first punted it around Ferrari’s private Fiorano track, everyone was delighted senseless by the F50’s poetic behaviour. But then this was home turf, and Fiorano’s surface is glassy-smooth, its bends constant-radius arcs like a geometry textbook. The first F50s have now rolled into the lock-ups of carefully selected owners (no speculators, no fair-weather friends of the marque, no bleedin’ riff-raff, grazie), and the order book is now chocka, right up to the end of the production run of 349, at circa £340,000 a pop (you pay in ECUs, and they don’t mean electronic control units).

Which is how come we’re revisiting Mohammed bin Sulayem in downtown Dubai. He’s got the car in his garage, the inclination and the roads to use it, and, blimey, the abandon to lend it to us. Herein lies another reason to be thankful the F50 is so forgiving to drive. In no real sense is this car insured: ‘Out here we have more faith in Allah than you do.’ Oh. He hops into his Landcruiser and I follow, straight from cold into the traffic and roadworks.

We’re running roof off, naturally. More than any of the other hypercars, the F50 makes sense with an open cockpit. It’s all about wringing every drop of sensation from a recreational drive. And although the hardtop is stress-bearing, it soon becomes clear that even without it, this advanced composites tub is absolutely rock-rigid. Even the usual open-car telltales, wind-screen and steering column, never flinch.

The tub’s a carbonfibre edifice, sandwiched with Nomex for strength and lightness. Pull up a little plastic tab to open the door (deadlocks? Don’t make me laugh). Drop over the sill into the red-and-black composites-shelled chair, a bucket so deep you can’t get coins out of your pocket. Carbonfibre weave is all around, encapsulated in liquid-gloss clear resin. Even the lower half of the dash is the same stuff, but a much lighter fillet, slightly flexible to a finger’s push. Nothing is heavier than it need be. It can be ornery stuff, carbonfibre, and in most cars where it’s visible, you can see a wiggly weave.

Not here: everything’s straight and true. Sheetmetal doesn’t get so much as a look-in. Kevlar is used strategically, and outer body panels are carbonfibre, too. Reflections in the paint betray the little chequerboard relief-pattern of the weave beneath.

One twist of the key lights up the black instrument faces, revealing blue markings in crisp italic script. Trouble is, they’re too dim to be seen in the Dubai sunlight. But the rev and speed needles themselves show up, so take note that when the tacho needle, which moves in little click-click increments, points vertically up, that’s the yellow line at 8000rpm. The speedo also runs clockwise, showing 0km/h at 6pm, 105 at 9pm and 190 (120mph) at noon. Soon after that the calibrations draw closer together, and it goes on to 360.

So it’s a cockpit of naked, but high-tech, sim-plicity and is immaculately finished. Three little leather-pouches, lovingly crafted from Connolly leather, take sunglasses, notebook and little else. But that doesn’t make it an entirely impractical car. Not impractical like the F1 car. You could at least drive it to the shops, even if you couldn’t bring home your sliced loaf. It’s an easy car to dawdle in.

It starts, literally, on the button. There’s a little rubber nipple below the key. Turn on, then touch it and the V12 fires cleanly. At cold idle it hunts a bit, sounding like a pair of fretful straight-sixes. But it isn’t noisy and it doesn’t stall. Its manners are perfectly satisfactory, which is amazing for an ex-race engine. The clutch isn’t heavy, either. Don’t know why not, given the task that faces it. The pedal box is a work of art, all in finely wrought alloys, with floor-hinged pedals easily controlled because your heels can pivot on a cross-bar provided exactly for this purpose.

Gearlever into first. It’s soon clear that this, Ferrari’s most frenetic car, has the company’s easiest-ever gearchange, light and sweet in its travel yet still fast and micrometrically precise. The lever doesn’t move under torque changes either, as the engine/gearbox assembly is bolted rigidly to the tub. Down the street, the F50 is wide but not uniquely so, and it’s easily placed by the crests of its front wings. The screen pillars are set well back and upright, like an old sports-racer’s or E-type Jag’s, clear of your field of vision. To look back over your shoulders, heave your torso up out of the seat. Not hard.

And the ride is just fine, thanks. This is where it could have all fallen apart for a supercar like this. Weld girders in lieu of dampers and you can make anything handle on a smooth track. But the F50 doesn’t deploy that trick. It has suspension. Oh, you know what shape the road’s in, for the springing is always firm, but shocks and vibes are filtered out. Gain speed so things smooth out some more. You’re not floating, because the electronically controlled dampers maintain their grip with iron resolution, and there’s not a molecule of slack because there’s no rubber anywhere in the suspension. Suburban dual carriageway now, heading out of town. The traffic clears ahead. Time to flex the ankle. Fourth gear, 3000rpm, a little less than 50mph. Go. Not a whole lot happens.

This engine needs understanding. It simply isn’t an any-gear/any-revs pulveriser. You need to work it to extract the real banshee power. Let’s explore. After that comfortable idle, the V12 turns up to 2000 without any histrionics. Creamy, zingy-sounding but nothing amazing. At just beyond 2000, it substitutes a rattly, harsh chatter for the song you’ve been hearing. That stays on stage until 3500. By then something is stirring. A baritone, Merlin-like throb, resonating with urge and accompanied by a definite gathering of impetus. From 4000 to 4500, it’s like a turbo cutting in, a feeling that torque is being piled on exponentially, that power begets power. And the noise? Yes, by this time you’re starting to get a taste, just a taste, of that shattering Monaco-tunnel howl.

But the F50 is easily out-dragged by other supercars at these revs: a Turbo Porsche makes 30 percent more torque at 4500, for the Ferrari doesn’t hit peak torque until 6500, when the Porsche has gone home. The F50 can rev to 8500, and that’s where you’ll find those 520 horses. In second gear, once you’re beyond 4500, the moment you open the taps should be the same moment you prepare to change up. The interval between the two events is negligible. All you register is a moment of calamitous, delicious, exhaust-explosion music, and a rabid bolt of g-force. Grab third with a quick forward snap of the lever and get back on the throttle. Again you barely mark the passage of time before fourth is called for. Back with the lever, noting that in this six-speed box the rev-drops for each gearchange are delightfully small, and also that the F50 has remarkably short gearing as well as outrageous high-rev power. Ferrari claims 202mph, which must be more or less rev-limited, and 0-60 in 3.7 seconds.

Eventually we find the straight road we need. It isn’t particularly long, and it doesn’t need to be. But it’s very, very empty. I turn the F50 at one end. Survey the heat-haze ahead. Just tickle the throttle in first, for full acceleration in that gear would be like smiting myself a gratuitous blow with a very large cudgel. Find second … floor it, red line, third, red line, fourth, red line, and fifth. That gearchange is at about 135mph, and things are getting breezy in here. The great 4.7-litre five-valve V12 is quite, quite furious now, sawing its way upward with a zeal you could simply never have imagined if you’d just explored its lower reaches. I’m too busy for stopwatches, but it’s a very short time interval indeed before we’re sailing through the yellow band again, homing in on a blurring 160. That’s enough. I back off before taking sixth, itself a pretty short gear by supercar standards.

I repeat this exercise several times, because the F50 seems to want it. It’s stable and content at big speeds, and I know it can stop. The brakes are colossal, non-servoed and breathtakingly able. The pedal asks for a hard push, which makes you question its reserves. Don’t. The more you ask, the more it delivers. This car loves big speed, but more than that it loves change: accelerating, braking, cornering. For these it was undoubtedly made.

The steering isn’t especially high-geared: it’s too precise to need to be. However little lock you feed on, you’ll always feel the car answer. There are urgent messages about the road surface chattering through the system, but remark-ably little kickback over bumps or tramlining under brakes.

In plain view, the F50 covers a similar piece of real estate to a Diablo or F512M, yet it feels dramatically less of a hulk (at 1230kg it’s 225kg lighter than an F512M but the difference feels greater). It’s so agile. And so friendly. In medium-speed corners, it’ll settle into a g-load and tell you exactly what it’s up to, how the front and rear wheels are coping. There’s no body roll, no slop. Even medium-speed bends can be taken at very high speeds in this car, so basically that’s about all that’s going to happen on the road unless you’re silly.

In lower-speed bends, tight second- or third-gear jobs, the F50 invites a more extrovert play-time. Barrel in and the steering lightens a touch, and the nose runs a little wide. Back off a mite and the front tyres dig right in again. Or gently open the butterflies instead (12 of them, right up in the inlet tracts). Now the back end starts to move wide, too, neutralising things in a nice little drift. Next time, you can crack those throttles wide open and bring the tail right round, as far as you like. Gathering it all up is straightforward, for there’s no harsh snapping: just hold whatever dose of opposite-lock is needed and ride the lovely slide. To say the handling’s as friendly as a Caterham Seven’s might seem a dire way of underselling a £340,000 car. But in the past, the rule has been the more you add power and grip and drama to the sports car mix, the more you lose those joys of a delicate and chuckable lightweight. The F50, like the NSX, is too good for that.

The engine is derived from the early-’90s F1 cars. Its cam profiles are different, to make the thing idle and bring in the power at 8500 instead of 14,000. It’s bored out, to boost torque, and a simple split-plenum variable induction serves the same purpose. Chains not gears drive the cams, to quieten the din. But there are still the five valves and still the titanium con-rods for sustained big revs. And still a notable paucity of low-to-mid-range torque. It has an iron crankcase, because it’s stress-bearing: the suspension loads feed directly through it to the bulkhead behind your seat.

The rear layout is very similar to a GP car’s, with pushrod suspension. By mounting the wishbones to the gearbox, they can be extra-long and exert more control on the dampers. Hence, partly, the excellent ride. Computerised control of the dampers’ valving helps, too, each corner being worked independently, rather than all four together as on the F355 and 456GT.

To make room for two people’s feet, the front damper/spring units are transverse rather than longitudinal as in the race car, but again they use pushrods. Titanium uprights and magnesium wheels help reduce unsprung weight, another Formula One obsession, and the suspension uses all-metal ball joints. Hardly surprising the car steers with such precision, but another reason to be amazed at its compliance. The body’s flat bottom, careful ducting and the rear wing all stem from F1 expertise and they give positive downforce, which is pretty unusual even among supercars. So are the tyres, custom built at Goodyear’s race department.

So, does it make you feel like a race-car pilot? I don’t know, because I haven’t driven an F1 car. Certainly, in the F50 you don’t have to cope with a race-car’s truculence at low speeds or crude racket flat out. And even out there on the highway, headlamps on as the Dubai night fell about my head, I couldn’t work up a Le Mans fantasy either. The F50 just isn’t difficult enough for that. So let’s forget the macho bit: it doesn’t have to be a white-knuckler to be great. It just has to thrill. Perhaps the hypercar era really is ending. If that’s true, then the F50 — less brutal, less fast even, than one or two of its predecessors — won’t just be the last of the line, it’ll also sit on the cusp of a new era where the driver matters as much as the car itself.

Read more iconic car features