► Old meets new in a special family tree twin test from CAR, 2012

► Two cars bookending the 911’s history head for the Furka Pass

► Perfect weather, mountain roads, and a pair of bellowing flat sixes

On CAR’s 50th birthday in 2012, we crowned the Porsche 911 our favourite car of the magazine’s 50-year history. Predictable? Perhaps, but with good reason. The 911 is the hardy perennial of the automotive world, a car that has defied attempts to replace it with more conventional machinery, to beat it with sleeker-looking rivals. And we go back a long way; almost to the beginning, in fact, the Porsche bursting onto the motoring landscape just a year after Small Car and Mini Owner, the magazine that would become CAR. We must have driven hundreds since, and over the last 50 years no other car has so consistently entertained.

But how to celebrate this ‘special relationship’? We could have picked one car and focused solely on that, but which one? Carrera 2.7 RS? A standard 993? A 997 GT3 RS 4.0? A brown 1980 SC Targa on cookie cutters with psychedelic Pascha trim? It was a hung jury, and besides, picking one car wouldn’t necessarily reflect the 911’s five decades of dominance. So why not, we reasoned, pick the two cars that bookend the model’s history, take them to some of the best roads Europe has to offer, and try to pin down exactly what it is about this oddball sports car that has kept us coming back for more for nearly 50 years.

Revealed to the world’s press at the 1963 Frankfurt motor show, Porsche’s upmarket 356 replacement was originally called 901 and featured a brand-new flat-six engine and a crisper 1960s update of the Beetle-influenced styling of its predecessor. Volume sales didn’t begin until 1965 however, when the car we’ve got here was built. In those intervening months it had gained a new name: 911, after Peugeot had kicked up a fuss about that middle ‘0’.

Log on to the Porsche car configurator today and you can build more variations of 911 than you could from a million Lego bricks. But it wasn’t always that way. The hotter 911 S didn’t arrive until 1966, the Targa, a year later. The 1970s heralded Turbo power, and the 1980s brought a full cabrio and, eventually, the first significant overhaul, encompassing power steering, anti-lock brakes and a four-wheel-drive option. In that first year though, there was only one body style and only one engine. So our car, pilfered from its slumber in Porsche’s majestic Stuttgart museum, is a plain old 911 Coupe. Like all pre-’69 cars, it rides on a short 2211mm wheelbase, the steel platform featuring four-wheel independent suspension, all-round disc brakes and the first example of the legendary flat-six, placed behind the gearbox, and so beyond the axle line to liberate sufficient space for two small back seats.

Sound familiar? It should, because the 991 parked alongside it follows a very similar recipe despite having 47 fewer candles on its birthday cake. The biggest differences are in their construction – the latest 911 making extensive use of aluminium for the first time beyond simple bolt-on panels – and their size. The 991 looks enormous, or the ’65 like a toy, I can’t decide which. Compared with the 4163mm length, 1610mm width and 1321mm height measurements of the original, the new one is 328mm longer, 198mm wider and 18mm lower, all of which has a dramatic effect on the styling. See the 991 alone and it’s clearly a 911. Park it next to a proper ‘neun-elfer’ and suddenly you’re not so sure.

But even the 991’s newfound girth is dwarfed by the epic backdrop for our story. Bond obsessives will know the Furka Pass as the road on which 007 and his DB5 track Auric Goldfinger’s Rolls, and engage in a little cat and mouse with Tilly Masterson’s Mustang. We know it as one of the great Alpine drives, a breathtaking mix of tight hairpins and fast, open bends, all set against a skyline of peaks so jagged they look more like a polygraph trace than a mountain range. There are some serious drops too, from corners sporting the vestigial guardrail equivalent of a Dairylea Triangle bikini top, and given that overcooking an early 911 into a corner tends to result in either massive brake-locking plough-on understeer, or terrifying lift-off oversteer, this is a road that asks plenty from a driver.

And from his car. It’s summer, and the place is riddled with tourists, so you’ve got to be ruthless with your overtaking even in a machine as powerful as a new 911, never mind a 47-year-old original. Not that we’re trying to conduct any sort of grudge match. Any thoughts of a twin test were left in the office. We’re prepared to be proved wrong, but the new car should be better in almost every way, as you’d expect given the 49 years Porsche has had to get it right. But what we’re really interested to see is if 911s old and new are linked by more than a shared three-number name and a few classic design cues. Let’s find out.

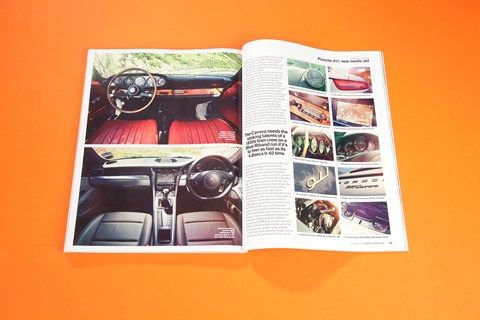

Old timer first. This is the first time I’ve driven an air-cooled 911 since I got rid of my Carrera 3.2 four years ago, and though they were built nearly a quarter of a century apart, the changes are clearly detail, not wholesale. There’s that same wraparound windscreen inches from your nose, the same awkward, floor-hinged pedals and straight-up-and-down wheel. Anyone who has ever driven an original Beetle will feel at home, too. Being an early car, this one’s lower dashboard and giant four-spoke wheel, are covered in wood, something still possible on the new car, but mercifully rarely seen. The ignition key’s on the left on this left-hooker, a trick from Porsche’s racing exploits when drivers could save vital tenths during a classic Le Mans-style start by simultaneously cranking the engine and selecting first gear. Spin the starter and the big central rev counter bursts into life as the carb-fed 2.0-litre flat-six in the back does the same, then settles down to a busy, splattery metallic idle, as the single tailpipe floods the air with a heady aroma of unburnt fuel.

Until the mid 1980s, 911 gearchanges always had a slightly imprecise, cartilagey feel to them, and on this early car, as on all pre-’72 911s (excluding the Sportomatic semi-auto), there’s the added confusion of the dog-leg shift pattern. So with a tug back and to the left to engage first gear, we head out of Andermatt towards the peaks that tower above, 991 following close behind. The old-timer doesn’t wait long to start making an impression. The steering is fabulous. Even at low speeds, it’s constantly streaming information in that old-school analogue way, like the Grandstand teleprinter, while your hands feel the 47 years of history from the patina of the wood in the deliciously thin-rimmed, but gigantic wheel. The messages are good ones, too, the old-fashioned 185-section balloon-sidewall tyres respond crisply to inputs, the slightest hint of a tilt away from the straight ahead tucking the nose into corners in a way that couldn’t happen if it was stuffed full of engine.

And that engine is a honey. Before the 1966 S arrived with its peaky cams and 158bhp, 911 ownership meant 128bhp 2.0 boxer power, take it or leave it. That doesn’t sound much by today’s standards, and even in 1965 it was only half as grunty as the 3.8-litre straight six of the E-type Jag you could have bought instead. But the 911 is relatively light at 1080kg, and the tiny red segment at 7000rpm reveals that this engine loves to rev. London might have been swinging, but not everyone in Britain was getting so high in the 1960s. With their sub-6k redlines, the only time you saw 7k in an E-type or TR4 was when wrong-slotting on the way up the ’box. Even the 991 only offers another 500rpm to play with. But we’ll need every single spin today. The 2.0’s twin Solex carbs are clearly in need of some fettling. It’s a pig to start and runs like a sack of scheisse below 4000rpm, meaning we’re trying to climb a 2429m mountain working with an effective rev band of just 3000rpm, accessed by what feels like five fairly rangey gears. How we laughed when we heard Porsche was developing a seven-speed manual for the 991; what we’d give right now to have one bolted up to the ’65’s flat-six.

As the pass climbs, the hairpins arrive. With so much weight over the rear axle, the ’65 car has plenty of traction coming out of the bends – you can see why it was such a hit on the rally stage in the late 1960s, 911s romping home in 1-2 finishes four years running from ’68-’71. Getting it into those turns is slightly more complicated. The light front end tends to wash wide, while steering that feels so lithe the first few degrees either side of straight ahead can kick back over bumps and weights up alarmingly when you need more than half a turn of lock.

When we stop half way up the pass for some pictures, I jump into the new car to sample 47 years of progress. Climb into any 911 up until the last 993 of 1997, and from the driving position, the cabin layout and design, and the ergonomics suited only to a caterpillar with a thyroid issue, there’s clear commonality. That all changed with the 996, the first water-cooled Porsche, and has been radically reinvented again for the 991. Yes, the classic design cues are still there: the iconic window-line over your shoulder and that familiar five-dial dash with the rev counter the star of the show. But that huge centre console, a theme borrowed from the Panamera and Cayenne, gives the cabin a whole new feel, completely bisecting front-seat space for the first time, and delivering the gearstick right where you want it, a mere hand-span from the wheel. The quality is breathtaking. Just eight years ago, Porsche was still selling the 996, a car with indicators that felt ready to snap off in your hand and the interior charm of a Korean supermini. Now the 911 has a cabin befitting the six figures many customers will spend.

Twist the key – and in a victory for common sense, it is a key, even if it looks like a Matchbox car – and the flat-six rowrrrrrs into life. The dominant whirr of the giant fan may have died when water replaced air as the 911 cooling medium of choice 15 years ago, but you wouldn’t mistake this for anything other than a Porsche flat-six. This one’s a 3.4 because the car it’s bolted to is the bottom rung on the 911 ladder, the £71,449 Carrera, a name first used by Porsche in the 1950s to commemorate success in the legendary South American road race. Essentially the same unit fitted to the Boxster S, only turned through 180deg and boosted by 25bhp, it produces 345bhp at 7400rpm and 288lb ft at 5600rpm, and comes within a whisker of delivering the entry-level 911 to a genuine 180mph on the autobahn.

We’re not on the autobahn, though, we’re on a mountain. As I pull back on to the roadand begin working my way past the dawdling tourists it becomes apparent that, lacking the 36lb ft boost of its bigger S brother, the Carrera needs the stoking talents of a 1930s liner crew on a Blue Riband run if it’s to feel as fast as its 4.8sec 0-62mph time implies. Leave the thing lugging out of the slower corners in second and it feels disappointingly lethargic, even the old car getting the jump on it for the first couple of yards. Get busy with the gears and that all changes. Porsche’s seven-speed dual-clutch PDK gearbox should seem like the obvious tool for this job, but unlike other manufacturers, Porsche is investing in manual transmissions too. And, while Ferrari might find this hard to believe, there’s more to changing gear than how fast you can do it. Some of us actually enjoy it. This latest 911 transmission is a beauty, light and slick, with a shortish throw and six well-stacked forward ratios, plus a leggy seventh cog for motorway work.

Keeping the rev counter in the sweet spot between 5000rpm and the 7400rpm limiter is no sweat with this ’box and now the 991 is strolling past the traffic. Only the small packs of sportsbike riders are making better progress today, and I’m eyeing up the ’65 for a see-you-later-gramps overtake, ready to leave it trailing on, well, not very much in the way of fumes thanks to a relatively modest 212g/km CO2 output. But then the road narrows, and a coach coming the other way is taking up too much of it for me to do anything other than stop and wait. Wait for it to amble by as I watch the slim-hipped old-timer disappear into the distance.

Traffic cleared, it doesn’t take much to reel it in. This 991 feels so much more planted than its ancestor, with far less understeer than 911s of old – and very old. The electric power steeringsystem is both quick and sabre sharp, and suffers none of the nasty kickback you get on the old car. But despite Porsche’s assertions to the contrary, the feel has been dialled back too. Not the feedback that tells you when you’re washing out on the limit, but those little nudges around the straight ahead, the comforting chatter that reminded you that you were in this together, you and the 911. Objectively, the new system is better; subjectively, it feels a little soulless. It’ll be fascinating to see what Porsche can do with it on the next GT3.

We stop for coffee at the parking area opposite the Hotel Belvedere, taking in the spectacular view of the Rhone glacier, which looks like a Swiss Mount Rushmore waiting for the first tap of the sculptor’s chisel. Britain has some incredible mountain vistas of its own in Wales, the Lake District and, especially, in Scotland. But this place is something else. A glance at the map confirms that, a few switchbacks down from the hotel, the road opens up. When I get there I’m driving the old car and it instantly feels more at home on these fast-flowing sweepers than it had on the way up the pass. The lack of lateral support from the PVC armchairs is never an issue and, if the body control and stopping power betrays this car’s age, the steering feels sensational. How does the new car compare on the same stretch? It’s in a different league, naturally. Faster, stickier, more planted and offering vastly improved braking, its only failing is that the chassis is almost too good for this engine. The Carrera 3.4 is a great car, but if you can find the extra £9793, the torquier S is worth the punt.

And if you can only find the £9793 and nothing else, try a used 996, which will still provide most of the very same sensations. Because, as our two 911s have proved, somehow, despite the pressures of emissions and crash legislation, of advances in technology, of massive changes in consumer taste and of fashion, 911s feel like kindred spirits whatever their vintage, sharing characteristics that go beyond mere design cues. The current 911 is the only car in its class that feels like a sports car first and a GT second, not the other way around. And it’s the only proper sports car with an extra pair of usable seats. It still sounds like a 911, still turns like one. And you still drive it the same way: slow in to get the nose keyed and stave off the understeer, early on the gas to make use of that legendary traction to fire you up the next straight. Few things in life last long without adapting to change; the ’65 car’s faults and, yes, our relief at handing it back after two glorious days says we wouldn’t want them to stagnate. But the latest 991 pushes the same buttons, elicits the same response that the original did when we first slid behind the wheel in 1965. It’s a worthy winner of our greatest 50 list. Here’s to the next 50 years.

Read more CAR archive content here