As personality transformations go, this one is proving less than obvious. I’ve just threaded my way into the new Esprit V8 from Lotus, and I’m heading up a damp A1 to the tune of a turbocharger whistle and a four-cylinder exhaust note. Lotus has been promising us a V8 motor for the past decade and a half, and now that we’ve got one, it seems to have missed the point.

Except that my last standing start, timed to splice with a gap in a never-ending road train of artics as I joined one of the busiest roundabouts in the world, elicited an explosion of wheel-spinning, stomach-compressing acceleration that has not, hitherto, happened quite this readily in an Esprit. The V8’s muscles have flexed. We’re in for an exciting time, soundtrack notwithstanding.

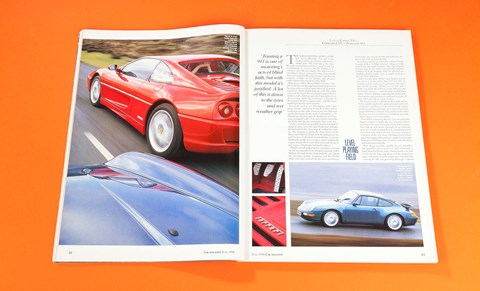

Behind my brilliant yellow Esprit are a bright red Ferrari F355 and a metallic blue Porsche 911. Three primary colours on a primary route, gathered together to answer the primary supercar question of the moment: with V8 power, has the Lotus Esprit finally cracked it as a credible rival to these greatest of cars from Italy and Germany?

No two cars better represent the Lotus’s nemesis. They are not direct rivals to each other, not least be-cause Porsche’s universal supercar costs £56,495 as a regular Carrera, while the Ferrari demands £88,965 of your personal equity as a berlinetta. But the Esprit shadows the 911 in price at £58,750, and mirrors the Ferrari in architecture with its mid-mounted 3.5-litre flat-cranked V8.

That the Lotus’s 32-valve motor delivers less power than the Ferrari’s 40-valver tells us a lot about how these cars are going to go. But the story isn’t as you may think: the Lotus’s 353bhp comes at 6500rpm, the Ferrari’s 380bhp at a scarcely believable 8250rpm. Turning to torque, we find a peak of 2951b ft at 4250rpm in the Lotus, 2681b ft at 6000rpm in the Ferrari. The Lotus is tuned for grunt, not bark. And although it loses out on a valve per cylinder, it has a pair of small turbo-chargers to force air into the engine throughout the rev range, while the Ferrari relies on suction and the resonances that result from its camshaft timing.

And the Porsche? It has to make do with just 285bhp, poor thing, despite having marginally the biggest motor at exactly 3600cc. Torque is less mountainous, too – 2511b ft at 5250rpm – although a Varioram inlet manifold (it functions as a single resonant chamber below 5000rpm, a two-stage chamber above that speed) optimises gas flow to match the engine’s speed and needs. Torque is up by around 301b ft between 2500 and 4500rpm compared with the pre-Varioram 911.

The German car’s air-cooled engine (dry-sumped, like the Ferrari’s) is, of course, slung out behind the rear wheels, which should make for some interesting handling comparisons when we get to our play-ground on the Yorkshire/Northumberland border. Especially as the forecast is for rain and more rain; thank goodness for modern tyre makers’ ability to squeeze out some grip where you’d think the laws of physics would render it impossible.

For now, though, I’m driving what is far and away the most visible car on the Al. Ironically, it’s also the car from which the Al is the least visible, especially when you look behind. The view aft, a case of tunnel vision in any Esprit, is even worse in this V8 because a huge rear wing, borrowed from the road-racer Sport 300, obscures half the picture.

When a Rover grille and a flashing blue light ap-pear separately and sequentially, I’m nearly sick. Of course I’ve been going faster than 70; who doesn’t? Damn the yellow paint! Damn our permanently guilty consciences! The police car edges past as though scrutinising every air vent on the Esprit’s body, a time-consuming task because there are plenty to see (including new extractors just ahead of the front wheels). Then there’s another Rover, a police security van, a third Rover, and we realise they’re not after us at all I hope they found it funny.

My day began in the Porsche 911, seeking out a back-road route to an Al rendezvous with the Ferrari. It’s a good way to break into the rarefied world of supercars, because the Porsche feels reassuringly normal with its upright windscreen, its airy cabin and its production-honed feel. This most enduring of supercars might have had a major facelift two years ago (little but the roof, doors and bonnet were left alone), but the aura is unaltered.

So is the slingshot acceleration out of bends, fat tyres biting, heavy tail squatting with the forces of traction. But there was doubt. Could a 911 really be this benign? Was the new rear suspension, all tailored for optimum camber and toe-in just when you need it most, really this good? As things seemed at the first exchange of keys, the Lotus and the Ferrari would need to be pretty special to justify a denial of the Zuffenhausen way.

And special the Ferrari is. That engine is enough to make you cry with happiness, even if you’re simply slogging up the Al. Its searing shriek is a sound all of its own, the flat-plane crank shaping a sound as of two highly-strung four-pots each competing for your undivided aural attention. It sounds this way because the firing intervals are 180 degrees of crankshaft rotation apart, at which point two cylinders will fire together. It’s better for high-revs power, of which the Ferrari has rather a lot, because you can tune the exhaust resonances more effectively.

The Lotus ought to sound like this, but doesn’t. Maybe I’m treading dangerous ground here, but I suspect that Italian ways of complying with EC noise regulations might be more inventive than those of the rule-abiding British. It’s certainly true in the field of food. Italians — French, too — aren’t as troubled as we Brits by Eurocracy, because they ignore it. The official line is that the Lotus con-forms to the latest limits (75dBA drive-by noise) while the Ferrari might need some modifications. Thing is, there’s more to sound than mere volume. How do you legislate for a tingle factor?

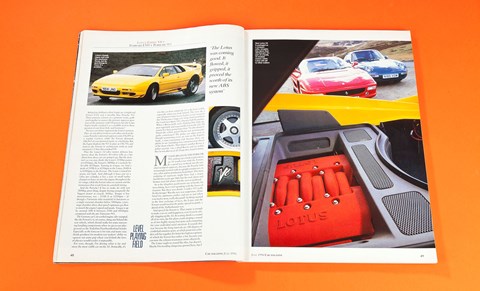

We meet the Lotus at the point where the truck-clogged Al crosses beneath the truck-clogged M62. At first glance, the Esprit looks remarkably ageless for an eight-year-old re-skin of a 21-year-old design. As well as that opaque wing and the extra air-extractors, the V8 gets a bigger mouth, an extra exhaust pipe, and the wheel-arch lips first seen on the Sport 300.

Taken together, these changes make the Lotus look surprisingly contemporary. It looks even more so with the optional flat-spoked alloys (ironically, they resemble a Bugatti Type 35’s) instead of our car’s split-rim items; both styles are made by OZ. Perhaps it’s the colour, but of the three cars it’s the Esprit that grabs the attention of dropped-jaw admirers. It’s a menacing-looking thing.

Inside, its age is more obvious. The facia is fragmented, made up of leather-clad glassfibre moulding piled upon leather-clad glassfibre moulding, and there’s little of the tailor-made charm that characterises the switchgear of the F355. It’s a bit of a parts-bin trawl, done rather long ago.

This is a cosy cabin, but not a very professional one. If there’s a tightrope between bespoke and bodge-up, the Lotus is in danger of teetering the wrong way. Nor is the walnut veneer — it adorns the doors and the instrument cluster — appropriate in a car as functional and technically literate as an Esprit sets out to be. And while this Lotus fits me to perfection, anyone with bigger feet would be un-able to heel-and-toe. Really tall folk wouldn’t even get their knees under the steering wheel, a tasty Nardi item which lacks an airbag (it’s an option). Perhaps that’s why the cabin feels dated.

The rain is belting down as we belt across Weardale. I’m still in the Lotus, and its gearchange is proving a major pain. The transaxle is the same Renault-sourced item as before except it now has synchromesh on reverse, but the linkage is re-routed to clear the new engine. The shift is not responding to finesse, timing, the things that should make for a pleasurable ratio-change. Add the soft response to blips on the throttle, and progress under duress is becoming less than fluid.

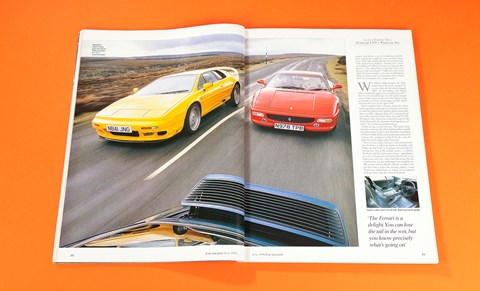

Behind me, editor Munro-Hall is having a fine time in the Ferrari, though his prancing horse won’t keep up with my yellow spirit when we’re power-ing out of a bend and blasting up a hill. The point is proved: the Esprit V8 is extremely quick where it matters, with a fabulous spread of urge right across the rev range. Turbo lag is minimal — a fraction of the four-pot Turbo’s response time — and the boost build-up brisk but not bombastic.

You don’t need to rev this engine, and it gets pretty boomy and buzzy if you do. Unless you’re looking to go into orbit, you can stay in a high gear and let the torque do the work. Lotus quotes a 70- 90mph acceleration time in third gear of 2.5 seconds, compared with 3.3 seconds for the four-cylinder Turbo S4S. By any standards, that’s a lot of g.

So the cantankerous gearshift matters less than it might. It takes away the edge of pleasure, though, detracting from the enjoyment of a rather fine chassis. The steering is quick, the most direct of the three, and while the Lotus feels the bulkiest car (in part because it’s the most claustrophobic), it can be fabulously wieldy just as long as you’re getting the engine and gearbox to do what you want. If you’re not, it gets a bit clumsy and hard to place.

Thanks to well-judged power assistance, you can use the steering wheel one-handed as though a filler, flicking through bends, balancing the car against the steering’s springy weighting and the throttle while you steel yourself for the next gearchange. Even in the wet you can do this, provided you ad-here to the slow-in, fast-out rule.

I’m feeling a bit heroic, given the wetness. To get to grips with a 353bhp supercar riding on wide wheels on a wet road. Fantastic. Then I get into the Ferrari, snug yet airy with its cream leather and low dashboard, body-hugging with its optional carbonfibre-shelled sports seats. A sports pack in a Ferrari. How ridiculous.

And I wonder what all the Lows-fuelled drama was about. Cue the cliché: the F355 feels like an oversize go-kart, once you’ve got used to the steering’s lowish gearing. At first, as you dive into a bend, you think the red nose is not obeying your commands, but it is — with linearity and fabulous clarity. There’s nothing exaggerated about the steering response, just consistency and total accuracy. It does what you ask, no more, no less.

The Ferrari really is a delight to drive with vigour. Every control matches the steering for precision and consistency of effort, even that clack-clack, metal-to-metal, gated gearchange once you’ve learnt the required firmness of hand. You can loose the tail in the wet, for sure, but because you know precisely what’s going on it’s not a fright.

A lot of this is down to the way you can meter the engine’s output so finely, the way it seems to have no inertia, no sense of reciprocation and rotation. You blip up and down through all six forward gears just for the devilment of it, something you’d never do in the Lotus. Or you can enjoy a plateau of power all the way from 1000rpm, from which speed the engine pulls without a single hiccup, right through to 8700rpm and a howl to wake the dead and make them chuckle.

Waft along in traffic, and the Ferrari mumbles and grumbles like a track car. Aim it through a quick downhill bend, with a bump on the exit, and you’ll feel the tyres dig deep, feel the suspension squat and check, hear the engine note tremulate like a Group B rally car powering through a special stage. What joy! Here’s a Ferrari that instils no fear. It just wants you to have a good time.

Meanwhile, where is the Porsche? On these wet roads, these fast, downhill bends, it’s surely going to get the better of one of us. I hope that I am not Fate’s chosen one as I head back along the road I’ve just driven in the Ferrari. Straight away, I’m bombarded with extraneous information. The steering’s weighting changes constantly as we traverse bumps and cambers, the tail squirms in slow corners as the traction control does its job of reining in the combination of power and tail-biased momentum, the front wheels understeer if you apply power too soon, dig in if you wait for the apex.

It’s much the most physical car of the three, the most demanding of an understanding of what’s happening underfoot. But it’s easy to sense this through the background noise of incidental inputs, and to drive through the 911’s little ways. Having done that, you’ll find it remarkably trustworthy and a whole heap of throttle-steerable fun. Trusting a 911 is one of motoring’s acts of blind faith, but with this model it’s justified.

A lot of this is down to the tyres, unidirectional Bridgestone S02s with groovy tread grooves and terrific wet-road grip. The Ferrari’s on Bridgestones, too — a bit of a coup for Japan, I feel — but it’s the earlier SO1 version of the Expedia design. Both cars have 225-section fronts and 265-section rears, all on 18in wheels and of 40 percent aspect ratio, apart from the 911’s 35 percent rear rubber. Neither can out-muscle the Lotus’s Michelin Pilot SXs (235/40 ZR17 front, 285/35 ZR18 rear), but they’ll do.

Trouble is, after the fireworks of the mid-engined pair, the Porsche feels a bit flat. Its merely very fast, not space-and-time compressing. The flat-six’s low-speed beat, high-speed wail is muted to suit our quiet world — still distinctive but not succinct. Don’t fret, though: the result is a car of splendid civility, made all the better by the smoothest, easiest gearchange of the three (six speeds here, too) and the way everything works just as expected. The three-speed wipers are proving useful, too.

The next day dawns wet, again, in sleepy Blanchland, tucked in a forgot-ten corner of Weardale. The Porsche looks purposeful in the damp air, but relatively normal. The Ferrari, however, looks fabulous: sleek, low and sculpted, it’s the perfect 1990s interpretation of the perfect 1960s shape that was the first of its line, the Ferrari Dino. Those outrageous air-scoops through the wide doors hint at further airflow trickery beneath, the visible end of a system of ground-effect ducts through a flat floor. This is why the F355 needs no disfiguring spoilers.

Inside, too, it exudes a sense of occasion far be-yond that of being a mere car; the drilled pedals see to that. Pity there’s virtually no storage space, apart from a pair of door pouches and a tray atop the centre tunnel. The Porsche does much better here, even running to a pair of tiny rear seats, but neither car has much room in the front boot. The Lotus has even less, but counters with a roomy rear boot be-hind the remarkably compact, crackle-red engine. The same space in the Ferrari is taken up with a serpentine exhaust, with alternative catalysts which switch to suit different parts of the power range.

The previous evening had ended dry, and in the run to the hotel the Lotus was coming good. It flowed, it gripped, it catapulted, it flaunted its new Kelsey-Hayes servo and ABS control system with stout stopping power. It proved it could be trusted.

It also rode the bumps every bit as well as the others, all three proving far suppler than their shallow tyre sidewalls suggest. And this morning its engine sounds better than I remembered, a deep, resonant burble — oddly 911-like — masked yesterday by closed windows and a hard-working heater. Shame the sound has to be so discreet, but that’s life.

There’s a morning’s moorland driving to do, then the journey home and the final reckoning for the Lotus. Outright performance figures must play a part here: the Ferrari is fastest (183mph, with the Lotus at 175 and the Porsche at 171), while the Lotus and the Ferrari level-peg for the 0-60 blast (both 4.8 seconds, with the Porsche at 5.4). And so should fuel efficiency, although our travelling has not been achieved with economy in mind. Here, the Lotus pays for the greatest usable pace with the worst fuel consumption: 12.7mpg against 14.9 for the Ferrari and 15.5 for the Porsche. You’d be hard put to do worse than we did.

Taking the Lotus back to Hethel, a blast of a drive through Norfolk once I’m free of monotonous trunk roads, I can reflect on the Lotus’s rebirth. This is a supercar like no Esprit before it, no doubt about that. You could hardly need more thrust. The chassis is up to speed with the speed, too. But… the gearchange is horrid, the cabin is not that of a £58,750 car, the details are not a delight to behold.

That’s where the others score, in the details. Never mind that the Ferrari’s a total gas, that the Porsche mixes bullet-proof build and practicality like no other supercar made. Pace isn’t everything, as long as you have enough. But the details matter because they colour your perception of a car’s values.

The most desirable car is the Ferrari, no question. Most people would buy the Porsche, use it daily, have a great time and be pleased at its lower cost. If you want Ferrari pace at a Porsche price, the Lotus is your car. Life at this level, alas, is not simple.

Read more CAR archive content here