► From the CAR archives

► We drive 959 and F40

► Published July 1988

The skies over Ferrari’s Maranello headquarters were lead-grey, and swollen with rain when we arrived in the Colgate-white Porsche 959. It was just after 8.15am and our Ferrari host for the day, the new PR boss, Giovanni Perfetti, was not yet at work. But those famous green gates were open, and some of the workers had already clocked on. Most stopped as they passed the 959, grit-mottled from its dash down from Stuttgart on the previous day.

It is not a pretty car, the 959, and nothing like as striking as the car with which we were about to compare it – the Ferrari F40. Those Maranello workers, I dare say, guessed our intentions, yet seemed impressed and complimentary, about the nearest thing the F40 has to a rival. They stopped near the car, peeked in through the 911 carry-over glass, smiled, waved their arms, whistled approvingly and chatted loudly.

Perfetti arrived soon after 8.30am – he wasn’t due in until nine, the security man had told us – greeted us warmly, and didn’t seem too surprised that there was a 959 parked a few feet away. We had not told Ferrari of our intentions. Yes, yes, they knew we were coming to drive an F40, the first British magazine invited to do so. What we hadn’t told them was that we reckoned the best way to evaluate the fastest-ever Ferrari was to see how it stacked up against the fastest-ever Porsche. Yes, Perfetti said, there would be no problem taking the 959 onto Fiorano, Ferrari’s private test track less than a mile from the Maranello factory. And yes, it was possible to go flat out, in Fiorano, in the F40 (‘but be careful, it has been raining and the circuit will be slippery’). In short, the two greatest supercars of all would shortly lock horns.

The drive down from Germany had reminded us, yet again, what a wonderful tool the Porsche 959 is. The flat-six 24-valve quad-cam engine, based on that of the 911 but using much of the technology gleaned from Group C racing cars such as the 956 and 962 punches out 450bhp, yet it is docile enough to allow the 959 to trickle through town with the Fiestas and Golfs. Also on offer are an electronically-controlled four-wheel-drive system, ABS brakes, adjustable dampers, a six-speed gearbox, a body utilising weight-saving Kevlar panels, and enough computer-controlled hardware to earn the 959 the title of most technologically advanced supercar yet built.

We stormed down the autobahn, occasionally nudging 200mph when the conditions were suitable. In most cases, they weren’t. Besides, 160mph seemed a comfortable cruising gait, especially as there were the odd drops of rain. At 160mph, the car was quiet, stability was exemplary, and the car felt unstressed, lolloping along easily. Even at 160mph, there was plenty of acceleration in reserve. Push the throttle to the carpet, and the engine note would deepen as the two turbos delivered more boost, and the car would jump. The danger threshold, we thought, was passed at about 185mph, 12mph short of the car’s true maximum. Over that speed, the car starts to wander a little, minute constant corrections are necessary on the steering wheel, cross winds begin to concern you, and you have to concentrate so hard that there is no real pleasure in cruising that fast. So, we backed off, and drove conservatively. Nonetheless, the 959 rocketed past the other autobahn traffic – we’re talking about Porsche 911s, BMW 7s and S-class Benzes, not just the small fry – with such remorselessness that the impression was of travelling by jet while the rest of the world goes by Tiger Moth.

A lorry would occasionally stray into the 959’s path, but each time those huge brakes would quell the car’s enthusiasm. It’s not just that the brakes are strong: they have such a delicate, communicative feel as well. And that’s all the more extraordinary when you remember that ABS is usually a feature that deadens feel.

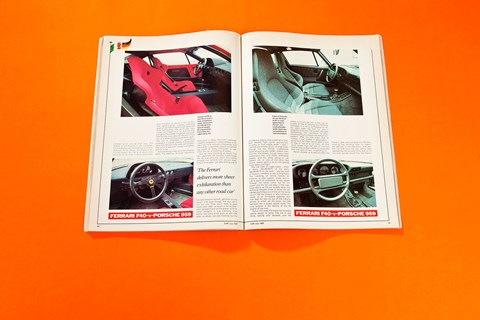

The Porsche’s engineers have paid a great deal of attention to the drivers environment, as you would expect. The clutch is beautifully weighted, and progressive. The steering, although power assisted, has superb fluency, but it suffers the slight deadness endemic to all 4wd sports cars. The gearchange is quick, and short of throw. There is the usual solid feel to the Porsche’s interior: thump the dash, or the door trim, and it feels strong and likely to last. The overall mood of the cabin, though, is undeniably 911 – from the steering wheel to the architecture of the dash, to the seats. Only the gauges would confuse the 911 owner, because, as well as the usual 911 ware, there is a water temperature gauge (for the liquid-cooled heads) and instruments that relay the state of such unlikely functions as the front-to-rear torque split, and the locking ratio of the rear diff. There is even a column stalk through which you can tell the transmission about the weather conditions – sun, rain, snow or gravel. A computer then automatically programmes the transmission to deliver optimum grip.

Most 959s also have an automatic ride-height control, but our lightweight sports-pack model (deliberately chosen as a more appropriate competitor for the F40) did not. A further control is the rotary switch which manually adjusts the damper settings; no matter what the setting, the dampers do stiffen automatically as the speed increases. Indeed, the suspension is one of the most extraordinary features of this most extraordinary of motor cars. Our overnight stop, before heading down to Maranello early the following morning was in a farmhouse outside Brescia, reached by a potted gravel road. The Porsche rode up that track better than a Jaguar XJ40 and a Citroen BX GTi, which had also happened to be staying the night. And yet, as the drive down from Germany had shown, the 959 rolls barely at all – even at the most astonishing speeds.

You’ll have guessed that, by the time we arrived at Maranello, we were somewhat enamoured of the 959. Could the F40, for all its power, for all its Ferrari breeding, possibly be better than the white car, just behind the Maranello gates? While we were wondering, an F40 pulled alongside the Porsche. It was red and low and wide and aggressive, and looked rather sensational parked next to the rather unhappily proportioned Porsche. If you wanted to turn heads, there’s no doubt which car you’d choose. Later it became clear: if you wanted to snap necks, the F40 is also better.

The test driver who delivered the F40 – a certain Claudio Ori – waited in the cars for a few minutes, before Perfetti gave them the all clear for the trip to Fiorano. Moments later the two-car £300,000 convoy (Ferrari £160,000, Porsche £145,000) tuned out onto the main Modena – Maranello road, took a quick right, and then turned into the road named after Gilles Villeneuve, just before the statue of the great little man, to the Fiorano circuit. A solitary guard, in a small cabin, lifted the front gate. Fiorano was deserted: green and lush and beautifully surfaced, lying empty under brooding black clouds that threatened to empty at any moment.

The F40 and 959 parked in the pit-road area, and Ori and Perfetti sought shelter in a nearby garage as they lit morning cigarettes. Can we go out on the circuit? ‘Yes, yes, but be careful, the circuit is slippery.’ Then they went back to their cigarettes, back to their chat.

So, there it was: the Ferrari F40, The car journalists the world over have been queuing to drive since its launch last summer. A car that has been displayed at motor shows all around the world, yet only been driven by Ferrari’s own test drivers. The car that succeeds the wonderful GTO as Maranello’s fastest sports car; its flagship.

It looks just like a group C racing car, what with its big rear wing and side skirts and deep chin spoiler, with front orifices for engine and brake cooling. It is not a beautiful car, not in the same was a GTO is. But once you’ve laid eyes on it, it is mighty hard to take them away. The finish of the body (mostly Kevlar-reinforced composite) is excellent, and the paint finish is better than the Porsche’s.

Open the driver’s door, using a GTB-style catch, and the first impression is of the extraordinary lightness. Little wonder it’s light, there is no trim inside. Instead, the door is a hollow composite shell, with a piece of plastic cord dangling inside. That cord, incidentally, is the rear door catch. Pull it, and the door opens. Owners of early Minis will find this feature of the F40 familiar. Slding windows will also make old-Mini owners feel at home – though in the F40 they are made of plastic, rather than the more up-market glass used in the Mini. In our test F40, the windows were awkwardly stiff to operate.

By the look of the door, and the exterior, you could be forgiven for thinking that the F40 is little more than a group C racing sports car for the road; look indie the cockpit and the impression is reinforced. Race-style seats that have massive side bolsters are just the sort of thing you’d expect in a Porsche 962: there are even a couple of holes in the squab for the racing harness shoulder straps. Our test car wore a conventional intertia reel three-point belt though, and it looked slightly feeble hanging from that seat.

There is no carpet in an F40, either (what do you expect for 160 grand?). Instead, the floor is simply uncovered composite material. Just like in a racer. The dash is covered in a grey felt-like material, as is the centre console. The roof lining is simply perforated vinyl (the same as in the Porsche). Luxury, there ain’t.

It’s awkward to clamber over the sills and the high-sided seats, and drop down into the racing chair, but once you’re in position things start looking good. There is a gorgeous three-spoke Momo steering wheel, which falls beautifully to hand, the gearlever, jutting out of the six-fingered metal gate, is just where your right palm would wish it. It’s a very Ferrari GTB-type lever: thin chrome stalk, capped by a round black plastic knob.

The sculpture of the dash is excellent, and the main dials all lie attractively and legibly, in the main binnacle, just beyond the Momo helm. The tacho is red-lined at 7750rpm. In the middle of the dash, pointing to the driver, are further gauges, for the oil pressure, fuel tank level and oil temperature. Already the message is clear: forget about any idea of matching the cosseting luxury of the 959. There is no-top grade carpet on which to rest your shoes, no leather-clothed dash or door linings. Why, there aren’t even any rubber caps on the foot pedals: all three are simply drilled metal. Have a little practice before the action starts, and you can soon tell that heel and toeing will be a joy. Easier than in the 959.

Turn the key, the ignition lights flash. Push the plastic starter button near the key, and the V8 twin-turbo engine, just behind your right shoulder, stutters into life, firing unevenly, tempestuously, at first. But give the throttle another dab, and the engine roars cleanly, and then settles down to a deep uneven growl.

The clutch is much heavier than the 959, and the spring loading of the gear lever is much stronger as well. Select first, down and over to the left, give the engine a few revs, for this car gives the impression that it would not be difficult to stall, let out that firm clutch and you’re on your way. Perfetti and Ori are still engrossed in their morning smokes, and seem not to notice as the F40 gingerly makes its way out onto the circuit.

The engine is not cammy, despite the uneven idling note. As with the GTO’s engine, on which the F40’s unit is closely based, it pulls easily from as low as 1500rpm, even in quite high gears. The tractability of the engine is astonishing: it can tootle along with the riff-raff, or hurtle past the best. Ferrari has always built superb engines, and the F40’s is one of its finest. It’s a slightly expanded version of the GTO unit – up from 2855cc to 2936 – and boost pressure and compression ratio are both increased, too. The upshot is that maximum power is up 19.5 per cent, to 478bhp at 7000rpm. That’s 28bhp more than the 959 can muster. The Ferrari’s on-paper performance lead is heightened by the Italian car’s weight advantage, of some 550lb. We were expecting the F40 to be the faster car, despite what we had just experienced in the 959, on that run from Germany.

We were not surprised. It only took a lap to confirm it: the F40 is faster. It probably doesn’t jump to 60mph, from rest, any quicker, for the Porsche’s four-wheel-drive is an unanswerable boon here. And, according to Ferrari’s own claims, the F40 is only 0.8sec quicker to 125mph, from rest. But where the Ferrari feels faster is in the important mid-range and top-end acceleration bands.

For a car that will be driven on the road – alongside the Escorts and Minis of this world – the F40’s performance is absolutely astounding It is a road car unlike any other: a machine that will venture onto the street and dismiss all other performance machines built before it with arrogant, disdainful ease. Only the 959 comes close.

The blowers deliver their urge from quite low down in the rev range, and explode into action at about 4500rpm. After that, the performance is plain frightening. The engine is screaming, making the sort of noise that comes from the back of Berger’s Ferrari every other Sunday, and the sharp red nose with its sinister spoiler and orifices gathers in the horizon with the sort of speed that means you don’t really have to be on top form to stay in control. Don’t misjudge your braking distances, your cornering speeds; don’t fumble your gear changes, or tread heavily or insensitively on that drilled metal right pedal, which can summon up more power than the throttle of any road car ever built. Damn it: this Ferrari F40 musters the sort of muscle that formula one cars used to deliver back in the pre-turbo days.

The noise is almost as overwhelming as the power. Forget about the distant wail of the 959, which becomes a full-blooded growl only at high revs. The engine of the Porsche is well-insulated: it’s noticeable and exhilarating, but never obtrusive. In the Ferrari, the engine is all. It’s the reason the F40 is so quick. And because it’s so loud, it totally dominates your thoughts, as you sit in the cockpit. The spine-tingling, riveting, bellowing growl of the F40’s engine is just about the most exhilarating note you’ll ever hear in the cockpit of a car. And it’s also just about the loudest. Forget about a quiet little Sunday drive down to the pub in this car, or a relaxing trans-Continental dash. This car is incapable of generating relaxation. It breeds anxiety and tension, yet it also delivers more sheer exhilaration than any car ever built, owing to its speed and its noise.

And mastering it requires sheer physical effort. The steering, although beautifully descriptive, is heavy, the clutch, although superbly progressive, needs athletic muscles if you’re to activate it frequently; and the brakes, unassisted, require almost the leg power of Daley Thompson to use when the car is travelling at speed.

And we were travelling at speed. The twin Japanese IHI blowers supercharge the V8, and send the crank revs racing towards the red-line with absurd ease. Snatch third gear, just after exiting one of the tight Fiorano corner, get back on the power, and even though the revs don’t run out until 7750, you’ll need to grab fourth soon after, so quick is the acceleration. Straight back on the power, and the motor screams in fury, silencing what seems like some wind gush as well (the tyres, no doubt, are also howling, but the thunderous engine note overwhelms that, too). Another tight corner approaches, so press on that middle pedal – hard – and blip the throttle as you change down through the box. Ferrari understands these actions so well; better, indeed, than Porsche. The brakes, though heavy, have tremendous feel, and terrific retardive powers, and the pedal set-up is just perfect. Ori, or one of the other test drivers, clearly spent a lot of time getting these details just right.

The F40 rides on huge rubber – Pirelli P Zeros, 245/40VR17s at the front, 335/35VR17s at the back – and the level of traction, needless to say, is enormous. The handling, at racing speeds on Fiorano, is also superb: sharp turn-in, just a touch of understeer as you power through the bend, come out on full power and the tail just does a little sideways as the car rockets down the following straight. Once or twice, the tail slewed alarming out of line on the damp circuit. Yet the chassis is very communicative, so an immediate opposite lock flick kept the red car out of the Fiorano Armco. In short, on the track, the F40 behaves like a pukka sports racer. The only surprise is the docility of the V8 engine at low revs.

Out on the road, this track-car tautness clearly exacts its price. The car is very firmly spring and damped, and the wheels communicate the bumps just as sharply as they do the steering and handling messages. It is not a comfortable car in the open road; but then nor was it designed to be one. The cockpit also gets oppressively hot. Ventilation is poor, sound and heat insulation are almost non-existent. After my first eight laps of Fiorano, I was soaked in perspiration – partly from the sheer mental effort it took to stay on top of a car that’s not that much slower than the sort of machine that wins the Le Mans 24 Hours, and partly because from the want of cool, invigorating air.

Ferrari allowed us to take the 959 onto Fiorano, after we’d sampled the F40 that morning (we returned later, to repeat the exercise in the afternoon). And yes, the car that only the day before had seemed like the quickest thing to ever hit the road, did feel slower than the Ferrari.

It acceleration urge was just that little bit more tardy; its throttle response just a little weaker. But, remember we are talking about a car that can hit 60mph from rest in 3.7sec, 125mph in 12.8sec and doesn’t run out of energy until 197mph. Remember, also, that a 959 had probably never been to Fiorano before. You’d expect a Ferrari to be faster around the track it was developed on.

The 959 still felt wonderful, despite its inexperience of Fiorano. Just a little more nose plough on the right corners, just a touch more body roll. On the slightly greasy surface, the 959 got its power down better out of corners. The gearchange, although less intimidating to Fiesta 1.1L drivers than the Ferrari’s, is actually a little more vague than the F40’s, although it is quicker of throw. The six gearbox speeds do not offer any major speed advantage over the five-speed F40: first, in the 959 is very low, and both cars have so much torque and power that five cogs are quite enough. Both cars have superb clutch progression, although the Porsche’s is, perhaps, slightly better. Like all the 959’s controls, it is certainly lighter.

The lightness helps make the 959 an easier car to drive than the F40. Add, too, the compactness of the Porsche, which occupies far less ground area, and its substantially better visibility. Apart from a few strange gauges, you could be in just about any car when you settle down behind the wheel. There’s carpet and leather and nice trim, and conventional seats. Inside, it feels only marginally more special than a mid-range Escort. Yet, on the road, or on the track, the car feels only marginally less special than its group C brother. That’s where the Ferrari is so vastly compromised: it feels and looks like an uncompromised racer, inside and out.

Yet it is not a racer. Ferrari has no plans to campaign the F40, because it would not be competitive in the group C category – not against the likes of the 962 or the Jaguar XJR-9 or the Mercedes C-9, all of which have a good deal more power than could realistically be extracted from the F40’s unit, and all have full monocoque racing chassis, as opposed to the old-fashioned (for racing) tube frame chassis used on the Ferrari. Given that it is no racer, fitments such as the lightweight Perspex sliding windows, those wraparound competition seats, the cord interior door handles, and the stark cabin, do start to look a bit silly. They are all annoying for road use, the very environment in which F40s will spend their time.

So how does the F40 stack up as a road car? It is sensational, no doubt. Both to look at, and to drive. Probably the most sensational sports car ever unveiled. It is certainly the most accelerative. The most exhilarating. Never before has a machine so overtly aping Silverstone machinery had the opportunity legally to drive down to Sainsbury’s. It is also beautifully made, a joy to examine in detail, and to touch. It is a much more exciting, gratifying car to look at, and observe, than the Porsche 959.

Ferrari plans to build just under 100 F40s (the original idea was to build 400), and they have all found buyers – such is the attraction of the Ferrari name, and such is the appeal of buying a car possessed with such blinding performance. Most, I suspect, will be bought by middle-aged men, very wealthy middle-aged men, who see the F40 as a source of stimulation as amusement, and as a way of getting as close as possible to the race track, without quite donning the Nomex and full-face. And there’s nothing wrong with that. Yet, the feeling around here is that the F40 is a strangely pointless machine. It hasn’t the beauty of the GTO, on which it is based, and which preceded it as Ferrari’s limited-edition flagship. And it’s never likely to gain the appeal, and pedigree, of past Ferrari Berlinettas such as the original GTO of 1962, the Le Mans, or the 250GT – cars that were built to race and which won major events. The F40 is too harsh, too impractical, for serious long journeys. It would be uncomfortable on long journeys. It is a racing car that can legally be turned loose on the road.

The 959 was built for a different purpose entirely. It is an older machine, conceived for group B racing, and later to become a mobile test bed for a host of high-technology features, some of which will find their way into future production Porsches. It has raced at Le Mans, and did well in its class. It was the single greatest product of the group B craze which swept car makers back in the mid-‘80s. Its sheer speed was the prime reason that the recent GTO, great car though it is, never raced. Ferrari knew that, against the 959, it stood no chance.

That is, I suspect, one of the main reasons Ferrari built the F40. To prove to the world it could build a faster, more exhilarating street-legal car than the 959. Ferrari has succeeded. For breath-taking excitement, the F40 is supreme. Yet, for all-round greatness, there is little doubt that the 959 is the better car. It would be quicker on a long trip, because it is less tiring. It would be quicker on an Alpine pass, in the hands of anyone short of Gerhard Berger’s talent, because it has better traction, and greater nimbleness. It would be quicker on slippery surfaces, thanks to the grip offered by its four-wheel drive. It is a far greater technological statement. In simple terms, the F40 is a superb engine wrapped up in a lightweight body. The 959 has a fractionally inferior power plant, but offers truly innovative transmission and suspension, both of which increase the speed, safety and comfort of the car. In short, the 959 is a technological milestone, likely to be remembered as the greatest sports car of the ‘80’s. The Ferrari will be remembered as the quickest car of its era, yet speed alone is no substitute for greatness.