► V4s are big in bikes – but not cars

► What are the pros?

► And what are the cons?

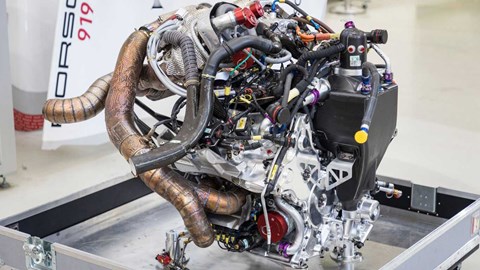

Thankfully, the trend of downsizing appears to be behind us. Porsche dipped its toes into flat-fours for the first time in decades, the Ford GT shed two cylinders and V8 displacements took a dive pretty much across the board. But while V6s, inline-fours and three-cylinder engines sprung onto the market in their droves, one smaller engine layout has always been ignored by the large manufacturers, except to power one of the greatest modern endurance racers.

Sign up to the CAR newsletter here for more exclusive intel, news and reviews

The V4 is an incredibly rare configuration in the world of cars, despite its prolific use in motorbikes. So why has it only been the likes of Lancia, Saab and Ford that have ever given this V-configuration some serious thought in their road cars in the past?

Engine balance

V4s can be rattly little engines, depending on the configuration that you go for. Having spoken to Neel Jani about his time testing the initial Porsche 919 development mules, he said that the 500bhp V4 created so much vibration that it became difficult to see and breathe when behind the wheel, often causing him to cough uncontrollably when driving flat out; not what you want in an endurance racecar.

Porsche solved the issue by simply switching the firing order, but V4s aren’t the most intrinsically balanced engines out there, with a 90º vee being the best way to achieve primary balance and get around having to use a balancing shaft to stop the engine shaking itself to bits.

Two of everything

The most clear disadvantage of this miniature vee-layout is the unnecessary complexity when compared to an inline-four. By opting for a V4, you end up doubling numerous components under the bonnet – cylinder heads, cam gearing, exhaust manifolds; it all starts to get needlessly messy and expensive to develop.

A cheeky way around the cylinder head issue is to go for a narrow-angled vee set-up, a strategy employed by Lancia and Volkswagen. You still end up with two exhaust manifolds but only two camshafts, so having the spark plugs dotted either side of a single cylinder head makes a V4 (or VR4) much more viable.

They can take up a lot of room

V-angled engines have a talent for taking up space in an engine bay, making a longitudinally-mounted inline engine seem impossibly spacious and easy to work on. If you opt for a nicely balanced V4 engine with a 90º vee, it can very quickly eat up the volume under the bonnet, unlike a slim, compact inline-four.

The Porsche LMP1 engineers will tell you that they went for the full 90º set-up (instead of a 60º option) to fill the space between the banks of cylinders with a honking great turbo and hybrid system to form something similar to the ‘hot vee’ layouts used by the likes of Mercedes and BMW. But such an engine would stretch out under a road car bonnet, leaving the engineers with a tricky packaging job.

What are the advantages of a V4, then?

Along with achieving primary balance when set at 90º, a V4 has the potential to create more power than an inline-four. That’s down to the crankshaft being shorter than usual, making it stronger and less susceptible to twisting under torque, meaning you can increase the revs and, in turn, the power output.

The crankcase is also better suited to managing the airflow within it compared to an inline-four, meaning that pumping losses are minimised and the maximum amount of energy can be transferred from combustion through to the wheels.

Will we ever see a V4-engined road car again?

You’d have thought that Porsche’s triple success at Le Mans with its 2.0-litre V4 turbo engine would have sprouted a couple of road-car projects, but sadly nothing came of it all, other than a stillborn concept car and the tech needed to produce a concept engine for the old 2021 F1 regulations (that’s sitting on a shelf in Germany somewhere).

Small inline engines are so embedded in the car industry’s mindset as cheap, simple ways to power a vehicle; 500cc per cylinder is the magic number these days, hence the huge amount of 1.5-litre triples and 2.0-litre four-pots. So the chances of a manufacturer deciding to opt for switching the cylinders into a vee-format, or even stealing a motorbike V4 for something super lightweight, seem ever so slim.

Let’s face it, if the likes of the Lancia Fulvia or Saab Sonnet were ever brought back from the dead, they’d almost certainly be EVs. So we probably just need to hope for the prancing pony of Stuttgart to think back to just how special the 919 was, and make it viable as a powertrain for the road. Porsche got slammed for its last foray into four-cylinder engines, but a miniature vee-engine could be a much more tasty proposition.