► CAR investigates autonomous testing

► Huge challenge of giving low-cost cars the tech

► Mars Rover boffins among experts

Tomorrow’s cars are being developed in the same way as yesterday’s: by clocking up thousands of arduous test miles. But as well as engines, brakes and suspension, testing must now also perfect the sensors, software and assistance systems rapidly becoming expected on even modest family cars.

Enter the boffins at PSA. The owners of Peugeot, Citroën, DS and now Vauxhall-Opel too have been working on their route to autonomous driving. It’s not about sci-fi futurescapes out of Blade Runner 2049 – it’s about putting in the hard yards on the road, planning for the worst, and not assuming that the highways authorities are in any hurry to enter the digital age.

We spent a day experiencing some of PSA’s prototypes. But first a quick spin through the Paris suburbs in a current production car, a Citroën C4 Picasso with a pretty familiar set of 2017-spec assistance kit: active cruise control (you set the speed and the distance, or ask it to aim for the legal limit), lane keeping assistance (which can easily be over-ridden if it’s foxed by peculiar road markings), active safety braking (spotting pedestrians and other potential hazards, and stopping the car if you don’t). So it’s mostly about helping the driver to stay out of trouble. Simple, intuitive, unintrusive.

And then we got into a Peugeot 3008 development mule, testing some of the technology that’s just a couple of years away from being fitted to PSA production cars.

Tomorrow’s tech today

Aside from an extra screen, a couple of stickers and some gaffer-taped wires there’s nothing unusual on the inside. Outside, it’s a regular 3008 but with a lot more scanners, sensors and cameras; most of the really clever stuff can’t be seen.

It has built-in mapping so that it always knows where autonomous driving is allowed (that’s mapping which works even if the GPS signal is weak). Because it can anticipate when autonomous mode will have to end, it flashes up a visual signal, and there’s a gentle audible tone to tell the driver it’s time to take over.

It can park itself. It checks you’re awake. It can spot pedestrians and wildlife 100 metres ahead at night. You press the Highway Chauffeur button and it will drive itself, in some circumstances. For instance, it can perform flawless overtakes: the driver indicates, but then the car makes a judgement about the timing and speed of the manoeuvre. (Yes, just like on the latest Mercedes S-Class, already in production, but at five times the price of a 3008.)

It’s remarkable how natural all this seems. It’s just a normal car that in some circumstances can drive more economically and more safely than a human driver.

Real people on board

Currently 20 prototypes are being run by PSA and its partners. The testing combines lab simulation with expert testers on road and track but also – since March 2017 – regular folk too. More than 1000 non-professional drivers have been out in autonomous prototypes on public roads. As well as finding out what aspects of the new technology need tweaking, and which sensor locations are best for avoiding dirt and damage, the tests are also providing valuable information about how the typical driver interacts with potentially intimidating self-driving features.

Carla Gohin, PSA’s head of innovation and research, is keen to stress the positives: ‘Some oppose autonomous functions to the pleasure of driving. But in fact, it’s an incredible opportunity: choose to drive or be driven; choose to have new on-board experiences; get more time for other activities; enjoy a new living space.’

She also highlights the gradual, incremental nature of the PSA approach, in contrast to the incoming tech companies – Apple, Google etc – who want to bypass the intermediate stages and go straight to full Level 5 autonomy.

When will this reach the showroom?

From 2020, most PSA cars will have the group’s new electronic architecture. This involves 20 sensors (12 ultrasonic sensors, six cameras, five radar scanners, one laser scanner), giving the car a 360º picture of its surroundings, and a view of 200 metres ahead; plus embedded HD mapping; vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure connective capability; a big bucket of algorithms enabling the car to make the right decisions based on all this information; and an interface enabling unambiguous communication with the driver.

PSA takes a belt-and-braces approach: pretty much everything has a back-up system, and the car must be able to work on the remotest rural back road, regardless of GPS or phone signal, albeit not in autonomous mode.

Electronics whizz, Eric Dequi, explains that PSA won’t be squeezing all of this tech into every car, although in most cases it would be physically possible as the scanners aren’t particularly big or heavy. ‘Not all drivers want to pay for all of this. This issue is cost, not technical, although size could be an issue if the engine compartment is very small.’

Is this stuff actually legal?

PSA’s Jean-Francois Huerre also emphasises the dangers of getting carried away with the possibilities opened up by digital developments. The Vienna Convention (the international treaty standardising traffic rules) allows Levels 1 and 2 autonomy (for instance, adaptive cruise control and active lane departure warning, both of which can be deactivated or over-ridden by the driver) but requires further negotiation before it’s legal to activate Level 3 (the driver can be ‘eyes off’, but able to intervene at a moment’s notice).

He anticipates that it will be 2020 at the earliest before drivers are allowed to do something else while the car drives itself. Insurance, training and licensing all need updating. ‘Who would trust an autonomous vehicle if you thought you’d face the legal and financial repercussions of your car crashing?’

Insurers, Huerre says, expect there to be fewer repairs required in the future, but the average repair to cost more, because of the need to replace expensive sensors.

The Martians have landed

Wind River has announced that it’s going big on real-world testing. What’s Wind River? It’s an Intel-owned company specialising in software for the Internet of Things, and it’s been involved in Mars Rovers, as well as working on the software in many military projects, trains, planes and the infotainment systems on millions of cars. They don’t use the phrase ‘mission critical software’ lightly.

Wind River has teamed up with the Transportation Research Center (the largest proving ground in the USA), the Center for Automotive Research at Ohio State University (the second largest university in the US, with a 9000-student College of Engineering) and the local authorities in Central Ohio for a programme of developing and testing connected and autonomous vehicles.

One of the attractions of Ohio is the presence of the Smart Mobility Corridor, which involves a cluster of tech companies focused on a 35-mile stretch of Route 33 between Dublin and East Liberty. It’s wired up with high-capacity fibre optic cable, linking researchers to data from sensors along the road, with more on the way. Government and some private industry fleet vehicles are wired up to provide data, too. The corridor could eventually extend much further – from New York to Chicago – as the US moves to position itself for the hotly contested title of world leader in the field.

Old meets new

Wind River’s general manager of connected vehicle solutions Marques McCammon understands better than most the crucial importance of putting in the miles. Unusually for a tech player, he’s from an old-school car industry background, having been at Chrysler when they launched the SRT division and with Saleen for the creation of the S7.

‘When you’re working in commercial aircraft, the Mars Rover, trains, robots in assembly plants… those systems really can’t afford to fail. We’ve been in automotive since 2005 in earnest. We’ve touched more than 100 million vehicles.

‘We have to find a meeting place between old and new. We have to find a way of getting 100-plus years of validating automobiles and bringing it into this area of AI, tech, software,’ he says.

‘Developing and testing new vehicles is an arduous process, in all weathers, all surfaces, over many miles. In Central Ohio we found this confluence of greatness. It’s an environment where testing is a lot more practical.’

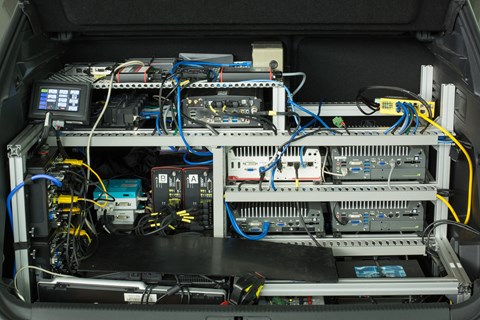

Wind River and its partners aim to create autonomous and connected ‘rolling lab’ test vehicles. The bulk of the testing will be away from the public, at the vast Transportation Research Center facility, which includes 4500 acres of road courses and a 7.5-mile high-speed bowl.

The TRC is in the process of creating the industry’s largest high-speed intersection, and detailed mock-ups of urban and rural roads. The use of Route 33 brings into play that extra element of reality: it has up to 50,000 vehicle movements a day.

Oily thinking for the digital age

Many future-mobility ideas aren’t from people with an automotive background, McCammon notes. This can mean they’re refreshingly free of baggage, but can also mean they’re far from practical.

‘If we can bring our experience – being around since the ’80s makes us a really mature tech company – together with car guys and academics, I think we can make something that consumers will benefit from. The connected vehicle is the closest thing to a moonshot the automotive industry has seen in five decades. It’s moving fast, and there’s a lot of money being invested.’

And what about the driving enthusiast? ‘Consumers are putting a lot of value on in-car apps, connected capability, autonomous driving ability, over-the-air updates, rather than all the places where automakers have historically invested: steering wheel, gas pedal, brakes.

But not every person who interacts with a vehicle thinks in the same way. Maybe automated functions can make sense on a 911 in traffic, but then you take back control on another part of the journey. There are reasons for excitement as well as caution.’

Check out more tech news here