► Vacuum cleaner brand axes EV plan

► Electric Dyson had been due 2021

► Dyson car was to be made in Singapore

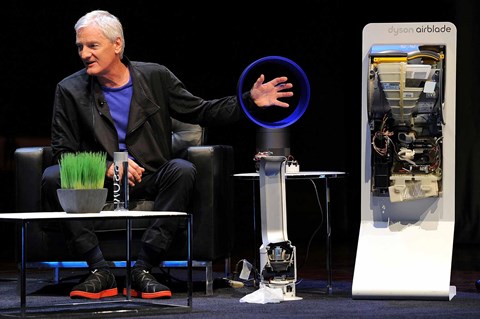

Dyson’s plan to branch out from making vacuum cleaners and pricey hairdryers is dead: the company is pulling the plug on its electric car project. It’s a blow to company founder James Dyson and his vision to disrupt the fledgling EV marketplace.

The Dyson electric car was planned to be made in the Far East; the British company had confirmed it would manufacture the EV in Singapore from 2021, where it’s also moving its headquarters.

‘Though we have tried very hard throughout the development process, we simply can no longer see a way to make it commercially viable,’ Sir James said in an email to staff, according to the Financial Times. ‘We have been through a serious process to find a buyer for the project which has, unfortunately, been unsuccessful so far.’

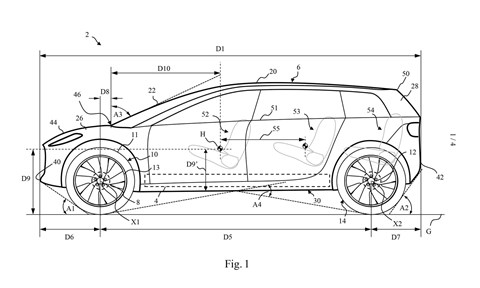

Patent filings (below) revealed the design of the Dyson EV for the first time, showing a monobox hatchback with the suggestion of some off-road ability. British inventor Sir James had previously promised it would be ‘radically different,’ although it is clearly not quite what our tongue-in-cheek artist’s rendering suggested (below)!

Big-diameter wheels were pushed out to the corners of the chassis to make the car ‘highly manoeuvrable… and improving handling on rough terrain’ while the patent filings also confirmed this as a five-seater car, with two rows of seats.

Why is Dyson moving its HQ and manufacturing to Singapore?

Many industry watchers have been disappoined by the company’s switch from the UK to the Far East – especially as its boss is a staunch Brexiteer. The location was chosen because of the local engineering talent, supply chains and proximity to markets such as China, already the world’s biggest electric car market. None of Dyson’s existing products are manufactured in the UK, which instead focuses on the R&D and intellectual property.

The car industry and Brexit: an explainer

Whispers of Dyson’s EV first appeated in the Government’s National Infrastructure Delivery Plan 2016-2021 which stated: ‘Dyson [is] to develop a new battery electric vehicle at their headquarters in Malmesbury, Wiltshire… This will secure £174 million of investment in the area, creating over 500 jobs, mostly in engineering.’

The revelation was quickly redacted in favour of: ‘The government is providing a grant up to £16m to Dyson to support research and development for battery technology at their site in Malmesbury.’ So how far along was Dyson in its EV plans, and what could its electric car have become? Keep reading for everything we know about the stillborn Dyson EV.

Inside the Dyson EV project

The British company had 400 staff working on the EV project, according to Dyson; he recently confirmed it had doubled the number of scientists working on its battery programme in the past year – and it was planning a recruitment drive to add further specialists.

The Dyson EV team is based in Hullavington in Wiltshire, away from the company’s main HQ in Malmesbury (before it moves to Singapore). It considered building electric cars in the UK, Singapore, Malaysia or China, according to Dyson, which also announced earnings of £801 million in 2017. That was up 27% on the previous year’s earnings.

Earlier in 2018, the company also revealed plans for a new 10-mile test track at its HQ in Hullavington. The new circuit was to be built alongside two renovated 1938 hangars on the 517-acre site to bring Dyson’s total investment on its electric car project to a cool £200m.

When was the Dyson car due to come out? On standby for a 2021 launch

Dyson told employees in autumn 2017 that the fast ‘adoption of oxymoronically designated ‘clean diesels’ spurred him on to launch in to the electric car market. ‘Some years ago, observing that automotive firms weren’t changing their spots, I committed the company to develop new battery technologies,’ he said at the time.

Dyson owns 100% of his eponymous company and has built up a £9.5 billion fortune, according to The Guardian.

The Dyson EV’s main weapon: solid-state tech

The Dyson car could have had double the energy density and range of today’s EVs, thanks to a breakthrough solid-state battery, and its $90m (£69m) acquisition of battery company Sakti3. The start-up, launched out of the University of Michigan by Professor Ann Marie Sastry, claims to have developed solid-state lithium-ion batteries producing over 400Wh/kg energy density.

That’s almost double the punch of Tesla’s Panasonic cells – reckoned to be the industry leader at around 240Wh/kg – effectively doubling an EV’s range while potentially slashing costs to $100 (£69) per kilowatt-hour, the tipping point at which EVs start to rival petrol/diesel-powered cars on costs.

Trouble is, battery history is littered with glorious failures such as Canadian company Avestor, which went bankrupt after the solid-state lithium-ion batteries it sold to AT&T started exploding inside U-Verse home entertainment boxes. So why do Sastry and Sakti3 (Sakti is Sanskrit for ‘power’ and three is lithium’s periodic number) think they have cracked it, where others failed?

Battery tech backbground

Today’s lithium-ion batteries are typically packed out with gels or liquids that don’t store any energy; Sastry’s dream was to discover a ‘solid’ conductive material diffuse enough to let lithium-ions pass back and forth from anode to cathode, discharghing and charging the battery.

So a decade ago, Sastry and her colleagues wrote simulation software to identify combinations of materials and structures around lithium that would result in high-energy batteries, that also could be mass-produced affordably. It’s no use having the best energy density or greatest number of cycles if they are prohibitively expensive to manufacture.

In prototype assembly of the micro-thin layers that build up the batteries, Sastry’s team modified secondhand equipment used to make printed foil crisp packets. In reality the same proven, thin-film deposition process employed to make flat-panel displays and photovoltaic solar cells will layer micro-thin films of cathode followed by the current collector, then the interlayer anode and so on – all within a vacuum. Once assembled, the resulting cells are charged and ready for testing.

Scaling up battery manufacturing from the lab test bench to series production is the big challenge, says Peter Wilson, Bath University’s professor of electronic and systems engineering. Dyson faces another sizeable challenge: increasing the size of its advanced digital electric motors from vacuum cleaners to powering a car. But if Dyson cracks it, the UK could have its very own Tesla rival.

The main tech innovations in Dyson’s breakthrough EV (now mothballed)

1) Solid-state battery

Although based on lithium-ion tech, the pressurised liquid electrolyte is replaced by a thin layer of non-flammable material that acts as both the separator (keeping positive and negative electrodes from coming into contact) and the electrolyte (allowing ion transfer to happen).

2) Safer than liquid

Lithium-ion batteries typically run at 35°C, demanding complex cooling for EVs, and both Tesla and GM’s batteries have suffered fires. To extend their service life, the batteries should never be fully charged or discharged. Solid-state batteries don’t suffer from these problems.

3) Clever motors

Dyson’s digital ‘switched reluctance’ motors benefit from excellent packaging and mechanical design, says Wilson. They offer good cooling and thermal performance – which is key – while aerodynamically efficient rotors, that are quiet and cool, minimise losses.

4) A question of scale

With brushless motors already 90+% efficient there isn’t a lot of headroom for Dyson’s digital motor. It will have inertia and thermal challenges if scaled up to car size, on top of losses generated by electric fields in the rotor. Using a series of laminations reduces these losses.

Further electric car reading

The best electric cars and EVs you can buy

How much does it cost to charge an electric car?

The best hybrid cars and plug-ins