► John Z DeLorean and the DMC-12

► Jason Barlow revisits the extraordinary tale

► An archive CAR feature from June 2005

‘Never judge a man unless you’ve walked a mile in his moccasins.’

– John DeLorean, quoting a native American Indian saying

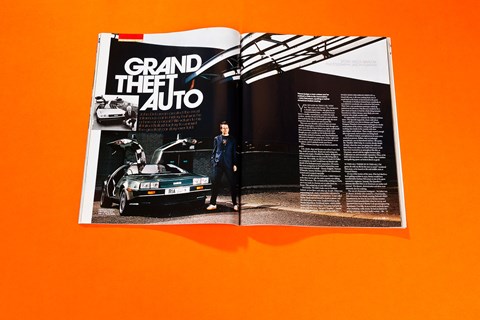

You sit low in this car, very low. You can’t see the bonnet. The windscreen is sharply angled and the side glass has an unconventional shape – not least because there’s a smaller, second piece set within the main window. Another theatrical flourish on a pair of doors that reach for the sky, the famous gullwings, the most impressive doors you’ve ever seen in your life.

Peer over your shoulder and you’ll spot yet more rakishly shaped glass, a set of louvres and, though you can’t see it, you also know there’s an engine underneath them somewhere, inches behind your head. And though you can’t actually see the bodywork either, memorably clothed in stainless steel, that flamboyant silhouette is branded on your brain. In fact, right now you’re inside what’s probably the most famous car on the planet, and it’s parked outside your house.

What a shame your legs are too short to reach the pedals.

DeLorean reborn for 2022: check out the new DeLorean electric car

I ate, drank, slept and dreamt cars when I was a kid. Big, small, fast and slow. Road cars and racing cars, saloons and coupés. Doodled the classics, designed my own, fantasised about one day actually being able to drive one. For a while, my dad had a Citroën GS Pallas as a company car and I would bore my friends with details of its hydropneumatic suspension. Of course, like most young boys in Northern Ireland they were more interested in football – Kenny Dalglish, Norman Whiteside, Sammy McIlroy and the rest, Manchester United and Liverpool especially.

But we all talked about DeLorean. I didn’t know it at the time, but in 1981 the entire country was talking about DeLorean. The car looked like nothing on Earth, yet it was made in a factory not 20 miles from my house. This rocked my 10-year-old world.

No wonder. We didn’t make cars in Northern Ireland, we just blew each other up. In 1981, Ulster was eviscerating itself, whole communities subsumed in violence and devastated by sectarianism. A man called Bobby Sands starved himself to death in prison, and the whole place went crazy. Sands had lived on the fiercely Republican Twinbrook estate, which swiftly descended into riotous chaos. DeLorean had built his factory next door to it. The word ‘Troubles’ – hateful journalistic shorthand – didn’t cover the half of it.

When John DeLorean died on 19 March 2005, it all came rushing back (not so much back to the future as fast forward to the past). Everybody in Northern Ireland knew somebody or was related to somebody who worked for DeLorean. That’s how a pre-production prototype ended up parked on my driveway. Not that you needed to be a pint-sized car fanatic to find the whole thing fantastic beyond your wildest dreams; more likely you were someone who simply needed a job.

It’s impossible to over-estimate the darkness of those times. The Specials topped the charts with Ghost Town, and there were riots in Brixton and Toxteth. Margaret Thatcher’s Government had begun its steady emasculation of the unions, setting itself against every working class family in the country with near-apocalyptic ramifications. There simply weren’t enough jobs to go round, and recession was biting hard.

In Northern Ireland, unemployment in some areas reached 30 percent. Belfast, once an industrial powerhouse, saw its hinterlands laid low. Of course, the ‘Troubles’ didn’t help; in a society already deeply divided, what else were you going to do with your time? Easy to see, then, how John DeLorean would have been received in an atmosphere like this; as Messianic, armed with his mighty business plan, Californian tan and remarkable reputation. Okay, so he didn’t ride into town on a white charger. But a stainless steel gullwing sports car looked almost as good.

‘Is this all there is? Is this all I’m gonna do with my life for the next 20 years?’ wondered DeLorean, as he mused on life mid midlife crisis at General Motors. It’s one of the ironies of this story. If he had died in a freak golfing accident in 1973, history would have recorded John Zachary DeLorean as one of the great automotive engineers. Instead, The Guardian’s obituary describes him as an ‘American car-maker and conman’. His dreams, determination and drive were ultimately also his undoing.

The son of a Romanian immigrant – his father was an abusive alcoholic who worked in a Ford foundry – John DeLorean was already running Packard’s R&D department by the time he was in his late twenties. General Motors poached him when he was 33, and appointed him head of Pontiac’s advanced engineering department. Crucially, in an era before anybody knew what ‘marketing’ really meant, he had an instinct for giving customers what they really wanted – the Tempest and Catalina helped to overhaul Pontiac’s dowdy image.

But it was DeLorean’s next project that shot it and him through the roof – the GTO (above). It was fast, cheap and cool, and it sold by the bucket load. It also helped position its architect at the forefront of contemporary ‘youth’ culture, somewhere he worked hard to keep himself even as the years caught up with him (he was also an early adopter when it came to plastic surgery). Soon, he was general manager at Pontiac; in 1969, he was put in charge of Chevrolet, GM’s most important division and the fourth largest business in the world in its own right. At 44, John DeLorean was a GM vice president, the youngest man in that starchy company’s history ever to have enjoyed such power.

At which point, the tale takes on a decidedly Shakespearean arc. DeLorean quickly got too big for his (cowboy) boots. Years later, in a never-before-broadcast 1996 television interview to which CAR magazine has gained exclusive access, he is uncharacteristically modest about his achievements at that time.

‘I couldn’t understand why I was being promoted so rapidly. There were people around me who had more charm and personality, who had been to better schools. And I ended up living a lifestyle I couldn’t believe. The tragic thing is, you start to believe your own press. [Looking back] I fully confess to becoming egomaniacal. You believe you are omnipotent, and you are surrounded by people who tell you what you want to hear rather than the truth.’

In that respect, he’s certainly not guilty of historical revisionism. The late ’60s DeLorean could have been an early prototype for the Sherman McCoy character in Tom Wolfe’s caustic satire of corporate high achievement, The Bonfire of the Vanities. He cut a rakishly dressed dash through the sombre GM management ranks. He divorced his first wife Elisabeth and married 19-year-old Kelly Harmon, ‘the embodiment of sweet, unspoiled American beauty – a conglomerate of good genes,’ observed legendary motoring journalist Brock Yates in an article for Sports Illustrated. DeLorean, 25 years older than her, was as maverick as you could get. Yet he rather disingenuously protested his innocence.

‘I get very tired of this swinger label,’ he told Yates. ‘I am really a pretty conservative guy. Look, I generally skip lunch and work out at the gym. I read an average of a book a week and spend most of my free time writing, lecturing and working on the problems in our cities and country – poverty, social inequality, housing, training of the disadvantaged. Now, does that sound like a swinger?’

In the 1996 interview, he’s rather more contrite. ‘I think my success was accidental. I was a talented engineer. I still am. In fact, I don’t think there’s a car running today that doesn’t have something I created. But I was lucky too.’

Then he tells a remarkable story about the time he helped four nuns stuck in a Californian forest change the spare tyre on their stricken car. ‘I happened to mention who I was and who I worked for,’ he remembers, ‘and then a few weeks later I’m in the executive dining room back in Detroit and Tom Murphy, GM’s vice president, says to me, “I want to thank you for helping my aunt out the other week”. I mean, statistically, how could that happen?’ God, clearly, was on his side. For now.

The DMC-12 is not a fast car. Twenty-four years after I first sat in one, I’m back in the driving seat of a DeLorean and this time my feet have reached a détente with the pedals. I’d be lying if I said I didn’t feel a little emotional. Let’s put it this way: it’s been a while since I’ve found 156bhp so overwhelming.

Yet this is a special car, in more ways than one. Its owner, 25-year-old DeLorean expert Alistair McCann, found it in a shed not far from his home in County Antrim. ‘I’d been looking for years,’ he says, ‘and there it was, just up the road all along.’ It gets better: Alistair’s car is Pilot 25, only the third car made, a pre-production model with a valuable provenance in the world of the devoted DeLorean aficionado (and these cars are now supported by a booming worldwide mini-industry).

‘It’s the oldest car in Europe,’ Alistair says, ‘and amongst other things it was used as the original road test vehicle. You’re a bit late, but at least you’re here driving it now.’ It’s a unique experience, even if the finished car – an expedient mish-mash of other people’s parts, if we’re completely honest – bore little resemblance to the product its creator originally envisaged. It’s a shame indeed that in his desperation to get the thing to market, DeLorean compromised his vision so much. But even he, a man with a vivid imagination, could never have predicted the serpentine turn of events that would have forced him to do so.

Having made it to GM’s 14th floor inner sanctum by 1972, DeLorean revealed himself to be exactly the sort of ideologue the US car industry reviled – consumer rights, civil rights, the safety and environmental lobby, he aligned himself with them all. He was publicly critical of his employers’ disdain for the consumer. There were allegations of impropriety with company funds. And then he left GM, with a few sweeteners to ease his departure. ‘John DeLorean has fired GM,’ the headlines crowed. The fast rising corporate superstar had sacked the corporation. Or so he wanted the world to believe.

The reinvention could begin. DeLorean began a process of seduction that would continue right up to his death. He made it known that he wanted to build an ‘ethical car’. Then it became an ethical sports car (presumably with higher ethical profit margins). He talked about corrosion-free stainless steel body panels and gullwing doors; of passenger safety and consumer-friendly running costs. Naturally Detroit recoiled in horror.

The next phase of the story unfolds in a way even a Hollywood screenwriter would dismiss as too fanciful. The DeLorean Sports Car Partnership offered investors the keys to a brave new world, and in return for tax relief raised enough cash to fund a trio of prototypes. DeLorean, ever the salesman, managed to recruit 343 dealers in advance of anything remotely tangible to sell, in exchange for shares in the company, raising another $10 million in the process. And after shopping the whole project around the world for nigh-on two years, finally the British Government – Jim Callaghan’s Labour Government – stumped up £54 million, and drew up plans to build a state-of-the-art 72-acre factory in the Belfast suburb of Dunmurry that would soon generate 2600 jobs.

Roy Mason, formerly a Barnsley miner and then Northern Ireland secretary, called it a ‘tremendous breakthrough’. DeLorean said that the plant would swiftly be producing 30,000 units a year, and that the car would be on sale in America within two years. Only one of them was telling the truth.

DeLorean hired Colin Chapman to do the engineering work, and against all the odds Lotus managed to complete development in 25 months. Chapman was paid $17.5 million through a Swiss bank account (via a Panamanian registered company called GPD Services. Though the invoices were sent there, Lotus was being paid directly by DeLorean Motor Cars Ltd in Belfast, a subsidiary subsidised by the UK Government. Go figure – the Official Receiver eventually did).

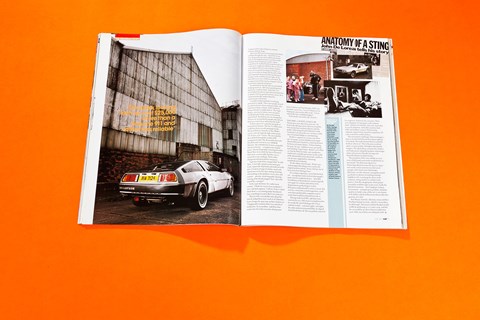

Now little more than a federalised Esprit, the DMC-12 junked most of DeLorean’s revolutionary thinking, and featured a centre backbone chassis with ‘Y’ forks front and rear. It had a glassfibre body, with stainless steel panels bolted on. Its front brakes came from the Ford Cortina, the rears from the Jaguar Mk IX. The engine was a wheezy 2.8-litre Renault V6. The gearknob was from the Renault Fuego, the glovebox latch the VW Scirocco. The door locks? Austin Allegro, apparently.

The 10-year-old me didn’t mind one bit: the DeLorean had gullwing doors and my dad’s mate Big Johnty, an engineer in the company, had brought one round for me to try. In America, the older, more demanding consumer – ‘the horny young bachelor’ DeLorean was targeting – discovered that this sleek looking lash-up cost $25,000. More than a Porsche 911 and, unfortunately, rather less reliable.

The Belfast workforce might have erected the factory in a frankly astonishing time, and their commitment was never in question, but car assembly was haphazard. The doors often didn’t fit properly, and had to be manhandled into place. If owners did manage to get into their cars, they often couldn’t get out again. The battery, meanwhile, was too weak. US chat show king Johnny Carson, along with Sammy Davis Jr DeLorean’s highest profile investor, was left stranded one night – he signed a lot of autographs.

Despite which, the car initially sold well: in fact, in the last quarter of 1981, it out-performed the Porsche 911. But it didn’t last. A severe American winter coupled with the grim fortunes of the US car market saw unsold DeLoreans begin piling up at Belfast’s docks. A nearby powerplant left sooty deposits over the shiny bodywork. In America, despairing DeLorean dealers spent thousands of dollars per car effectively rebuilding them. In Belfast, despite another loan from a highly sceptical Margaret Thatcher, the money was running out (a grand total of £84 million would be lost).

And this amidst growing evidence that DeLorean – operating from an extravagantly furnished Manhattan penthouse – wasn’t just blowing taxpayers’ money on a doomed vanity project, he was siphoning off funds for his own benefit. He had certainly entered the Guinness Book of Records, having now flown on Concorde more than anyone else. The endgame was looming.

How did DeLorean wind up in the middle of an FBI drug sting? Even he couldn’t figure that one out. The fact is, he was arrested in the LA Sheraton Plaza hotel on 19 October 1982, having allegedly taken part in a plot to smuggle 100kg of cocaine – street value an estimated $50m – that he described as being ‘better than gold’. He later claimed that he would have done anything to save his ailing car company, but cocaine smuggling?

In the 1996 interview, he strenuously denies that he knew anything about the exact nature of the transaction, even as he sank further into a trap that unfolded over a four-month period. ‘When I said, “I don’t wanna go to California, I don’t want anything to do with you guys” [the government agent] said, “It’s too late for that buster, you come along or we’re gonna send your daughter’s head home in a bag.” So I was a total disaster. A basket case.

‘I admit I’d been struggling, looking everywhere to find money to keep my company alive. But the whole scenario in that room was a shock to me. That was the first time I really thought they were talking about drugs. I didn’t think I was gonna get out of there alive. I thought they were gonna kill my kids and kill me. I was scared shitless.’

Two years later, in August 1984, and after a 62-day trial, DeLorean was acquitted by an LA jury on eight counts of conspiring to possess and distribute cocaine. This was a case of FBI entrapment, it was concluded. DeLorean, who claims that $43 million was spent and 243 agents deployed in an effort to nail him, actually denies that it was entrapment.

‘Because no crime was committed. I never gave any money. I never took any money,’ he says indignantly. ‘The public perception and the truth are quite different. I had a dream. I killed myself to put it into effect. I don’t think I did anything wrong.’

Right up to his death, a warrant was still out for his arrest in the UK, and though various people were punished for their role in the affair – not least Fred Bushell, the former chairman of Group Lotus, who was sentenced to five years for fraud in the early ’90s – John DeLorean himself managed to evade the law on two continents more or less unscathed. This despite the Official Receiver uncovering ample evidence that he had duped numerous private investors over the years as well as the British Government, and had diverted money via a web of dummy companies into his personal accounts.

He didn’t get away scot-free, though. He lost his New York apartment in 1992. Bankruptcy proceedings in America concluded in May 2000, the many creditors receiving 91 cents to the dollar. A federal court then seized his New Jersey estate. In the end the man who had once been worth about $170m was left virtually penniless, saddled with vast legal bills, his reputation in tatters. Yet he remained convinced of his innocence, though not so convinced that he was prepared to return to the UK to clear his name.

‘I’ve already been acquitted. Why spend another million dollars and six months? To what purpose? I don’t think there is any law [in Northern Ireland]. You’re a country with no due process. If I ever went over there I’d be insane. Look at what you’ve done with the Guildford Four and the Birmingham Six. You find what you wanna find up there. If you want to put somebody in jail, you’ll find a way.

‘I’ve made mistakes in my life, I admit. But I’ve never done anything dishonest.’

When John DeLorean died earlier in 2005, a story that I’ve been obsessed with for almost 25 years concluded. Driving the car around Belfast today is the postscript. Objectively speaking, the DeLorean is slow, it doesn’t really handle and there’s more entertainment to be had out of monitoring the reaction to it than actually driving it. But I just can’t help loving the thing.

Objectively speaking, DeLorean the man was a fraud, a liar and a cheat. Even at his most penitent, his comments were laced with a vainglorious self-interest. Hardly a positive role model for your kids, sure. But I’ll be telling mine the story of the car with the gullwing doors and the man who made it.

If you enjoy insightful, original storytelling, buy CAR magazine each month. Click here for more details of how to subscribe